Analysis

#6: VVPAT

Petition before Supreme Court to direct the Election Commission of India to verify a higher number of VVPAT slips.

This post is a part of our 10 Cases the Shaped India in 2019 series.

Issue:

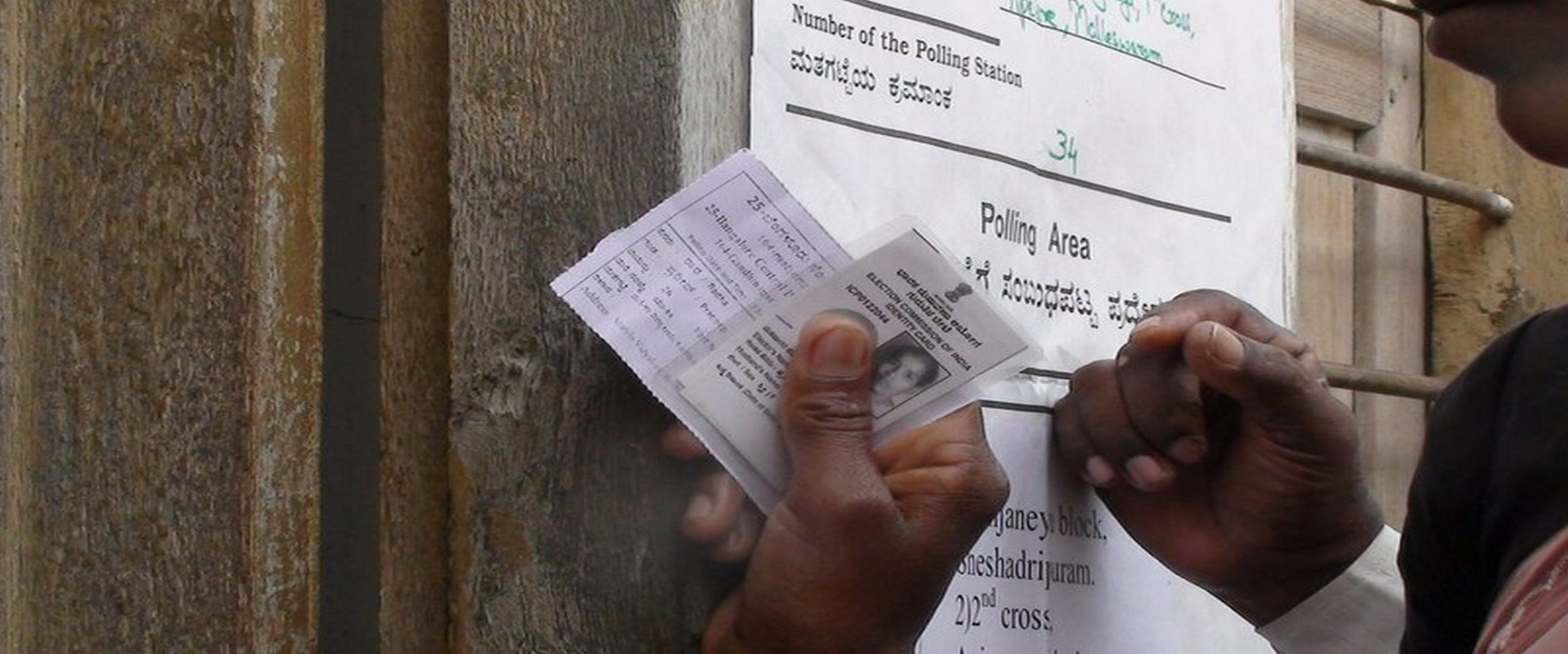

Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail (‘VVPAT’) is an independent vote verification system, which allows a voter to check whether their vote was cast correctly. In 2017, the Election Commission of India (‘ECI’) decided to undertake mandatory verification of VVPAT slips in one randomly selected polling station per Assembly Segment/Constituency. In February 2019, the then Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, Mr. Chandrababu Naidu and a number of other political leaders, approached the Supreme Court to direct ECI to verify a higher number of VVPAT slips.

Specifically, the Petitioners requested the Court to quash the EC guideline of verifying VVPAT slips in only one polling station and direct it to verify 50% of VVPAT slips in each Assembly Segment/Constituency.

Did the Supreme Court direct an increased verification requirement?

On 8 April 2019, the Supreme Court ordered the ECI to increase the number of EVMs that undergo VVPAT physical verification from 1 to 5 per Assembly Constituency or Assembly Segment in a Parliamentary Constituency. Soon thereafter, the Court briefly heard the review petitions but declined to modify its order.

VVPAT Timeline:

Impact of Supreme Court decision:

Increase in number of VVPAT slip verification pre and post-2019 judgment (Source: India Today)

Recent petitions filed by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) and others have pointed to an irregularity in the final votes counted when compared against the voter turnout in the 2019 elections. Court has now issued notice to the EC in the matter. If the allegations are found to be true, the role of VVPAT slip verification may come into limelight even more.

Must Reads:

- A brief explainer on what EVMs and the role they play in the conduct of free and fair elections.

- Srinivasan Ramani argues that while improvements to EVMs and VVPATs are needed, a return to paper ballots is untenable. He notes that there exists no evidence to show that large scale EVM manipulation has taken place. He urges for ‘a continuing and constructive critique of India’s EVM’ to increase trust in them.

- Shamika Ravi et al study EVMs in State Assembly elections and find that election fraud has decreased since their introduction. Further, they find that EVMs have increased the turn out of ‘vulnerable sections’, such as women and SC/STs.

- Rajendran Narayanan and Nikhil Dey argue that the Election Commission must verify 100% of VVPAT slips, in instances where an error is detected in the audit process. They claim that even a single mismatch vitiates trust in free and fair elections.

- Ronald Rivest introduces the notion of software independence in voting systems. He calls a voting system software independent if an undetected error in the software has no effect on the outcome of the voting system. VVPAT can meet this definition. He puts forward that a software independent approach will show voters that errors/fraud can ‘reliably be detected’ and in cases where they are not, it will have no effect on the outcome of the election.