Analysis

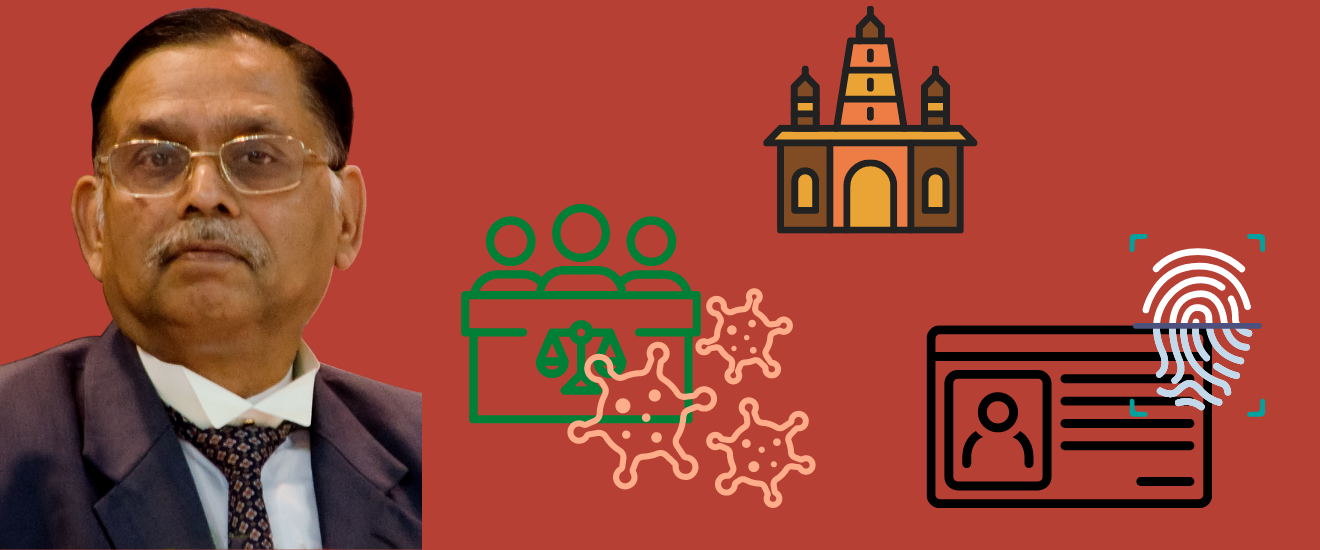

J. Bhushan’s 11 Key Judgments on Reservation, Privacy, Religious Rights

Bhushan J's opinions have left an impact on reservation law, while he dealt with multiple COVID relief cases and Ayodhya disputes.

Justice Ashok Bhushan will retire from the Supreme Court on July 4th 2021. During his tenure, he adjudicated upon important matters of religious rights, privacy, reservation and COVID crisis management.

In this post, we look at some of his most crucial judgments.

Ayodhya- Property suit or Religious Dispute?

Justice Bhushan joined the five-judge bench hearing on the Ayodhya land title dispute in M. Siddiq v Mahant Suresh Das . Bhushan J’s addition to the Bench came in after Justices Ramana and Lalit recused themselves. The Ayodhya judgment marked the conclusion of one of the most widely discussed and contentious legal disputes in recent times. The Bench overturned the decision of the Allahabad High Court, which divided the suit property between the Muslim and Hindu parties. The Supreme Court Bench instead decided the case on minimalist reasoning, focusing on the title issues instead of the juristic personality of the disputed land. The judgment was unanimous but unusually, did not identify the author. It granted the entire disputed land to the Hindu deity, Sri Ram Virajman.

Before deciding the title dispute, Bhushan J had authored the majority decision, for himself and the then CJI Dipak Mishra, refusing to refer the 1994 Ismail Faruqui judgment to a larger bench for reconsideration. In this judgment, a constitution bench of the Supreme Court had held that since Namaz can be offered anywhere; offering Namaz in a mosque was not an essential practise in Islam protected by Article 25. Accordingly, the 1994 judgment held that the State government of Ayodhya had not acted unconstitutionally in acquiring the Babri Masjid land. Bhushan J’s majority verdict held that the Ismail Faruqui judgment was valid law, and did not have any bearing on the civil issues in dispute in the Ayodhya land title case. Nazeer J wrote a dissenting opinion in this case.

On Caste: Who can demand ‘concessions’?

Heading the five-judge Bench in Jaishri Laxmanrao Patil v Chief Minister, Maharasthra, Bhushan J delivered the judgment on behalf of himself and J. Naseer. He read down Sections 4(1) a and b of Maharashtra’s Socially and Economically Backward Classes Act, 2018, which granted reservation to the Maratha community in higher education and public employment. In doing so, he held that the Marathas were not a Socially and Economically Backward Class. They did not fall under the exceptional category for which reservation could be provided beyond the 50% cap set in Indra Sawhney v Union of india.

Bhushan J’s interpretation of the Constitution (One Hundred and Second Amendment Act), 2018 forms the minority view in this case, and hence, is not binding. He held that the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC) must consult the States in a ‘meaningful, effective and conscious’manner on all policy matters with regard to backward classes, including reservation. The majority’s interpretation of the Amendment is expected to have far-reaching consequences on communities other than the Marathas.

In Union of India v M. Selvakumar in 2017, Bhushan J held that all those belonging to the ‘physically disabled’ category suffered from similar disabilities, irrespective of their caste status, and so, must be treated alike while considering concessions. Accordingly, he decided against a plea seeking an increase from 7 attempts to to clear the Civil Services Examination for ‘physically handicapped’ OBC students, to 10 for ‘physically handicapped’ OBC students.

Aadhaar Does Not Violate the Right to Privacy

Section 139AA of the Income Tax Act, 1961 required all those eligible to obtain an Aadhaar Card to link it to their PAN Card and income tax filings. In 2017, Bhushan J along with Sikri J held that this Section could not be challenged as unconstitutional on the basis of the right to privacy. This was because the 9-judge Bench to decide the validity of the right to privacy was yet to be constituted. In effect, Bhushan J’s judgment granted limited relief in removing the adverse action against those who had not linked their Aadhaar cards to their PAN cards, but required that all those who had Aadhaar cards must do so.

In 2018, Bhushan J wrote a concurring judgment in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v Union of India, upholding the constitutional validity of the Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act, 2016. He held that it did not violate the right to privacy, as it passed the three-fold test of legality, need and proportionality laid down in the Puttaswamy judgment.

On Judicial Proceedings and Matters of the Bench

In Kalpana Mehta v Union of India, the Court had to adjudicate on whether it can rely on the report of the Parliamentary Standing Committee and issue directions while exercising the power of judicial review under Article 32. In his concurring opinion, Bhushan J opined that Parliamentary Standing Committees reports were admissible in Court as evidence. But their admissibility did not raise the presumption of truth. All contents of these reports would have to be verified independently.

In Shanti Bhushan v Supreme Court of India, Bhushan J wrote a concurring judgment reiterating previous holdings of the Supreme Court that declared that the Chief Justice was the master of the roster of the Court. Bhushan J, along with Sikri J, rejected the prayer to read ‘Chief Justice’ in the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 to mean ”collegium’, so that allocation of cases would be decided by the five senior-most judges and not the CJI alone. This petition was filed against the backdrop of insinuations of judicial corruption by members of the Bar, and a statement from four senior-most judges of the Court expressing concern over the State of affairs at the Court.

Welfare Orders to Manage Covid Crisis

In Shashank Deo Sudhi v Union of India, Bhushan J had initially, on April 8th 2020 directed the Central Government to ensure that COVID-19 tests were free for all at both government and private hospitals. On April 13th, this order was modified to hold that such free testing in private labs need only be made available to those who are eligible under the Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Aarogya Yojana (‘Ayushman Bharat Yojana’).

In a suo moto case titled In Re: Problems and Miseries of Migrant Labourers, Bhushan J issued orders requiring the Central and State Governments to provide transport to migrant workers to return to and from their home states. He also directed quick and efficient implementation of the ‘One Nation, One Ration Card’ Scheme, to ensure that migrant workers can claim ration supplies in all states. He ordered the registration of unorganised sector workers so that they can claim ration and other benefits under various schemes.

On his last day at the Supreme Court in Reepak Kansal v Union of India, Justice Ashok Bhushan, with Justice MR Shah, declared that it is mandatory for the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) to frame guidelines for payment of ex-gratia assistance to the families of those deceased due to COVID-19. He held that no power of judicial review exists over the amount of compensation the Government decides to pay. However, he exercised the power of the Court to ensure that the NDMA was fulfilling its statutory obligations by directing that ex-gratia payment must be one of the Minimum Standards of Relief contemplated by the Authority.

See our post that examines his tenure as a Supreme Court judge in Numbers.