The Supreme Court’s authority stems from the Constitution of India, 1950

As the highest court in India, the Supreme Court’s judgments are binding on all other courts in the country. It serves both as the final court of appeals and final interpreter of the Constitution. Owing to these vast powers, many have labelled it among the most powerful courts in the world.

Admission of Cases Before the Supreme Court

When a case is filed at the Supreme Court, the registry of the Court first examines it for filing defects. These defects may include missing annexures or failure to grant power of attorney. If there are no defects, it is registered as a Special Leave Petition, Writ Petition, or any other category it may belong to. In an event where the registry identifies filing defects, it is identified as an ‘unregistered case’. The party is given the opportunity to ‘cure’ the defect, and once cured, the case is registered as a regular admission matter.

Certain cases, such as statutory criminal appeals (for example, those involving the death penalty), automatically proceed to regular hearings. However, most cases require a preliminary hearing to determine whether they can be ‘admitted’ to the Court.

At the admissions stage, the case is heard by a Bench of two judges who decide whether to ‘admit’ the case for ‘regular hearings’. These admission hearings are conducted every Monday and Friday, and are known as miscellaneous days. A Bench may hear 50-67 cases on each miscellaneous day. In deciding whether to admit a case and issue ‘notice’, the Bench usually hears each matter for only a few minutes.

A miniscule proportion of the cases that are instituted at the admissions stage are admitted for regular hearings. Regular hearings are held on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays. During regular hearings, the Court is able to hear arguments from both parties and deliver a judgment based on the merits of the case.

Advocates in the Supreme Court

Who may be an Advocate before the Supreme Court?

The Advocates Act, 1961 recognises two types of advocates: Advocates and Senior Advocates.

The Supreme Court specially recognises a third category of advocates known as Advocates-on-Record (AOR) who are exclusively entitled to ‘appear, plead and address the court’ or to instruct other advocates to appear before the Court.

Who are Senior Advocates and how are they selected?

Section 16 of the Advocates Act, 1961 empowers the High Court or the Supreme Court to designate an advocate as a ‘Senior Advocate’ based on their standing at the Bar, ability, special knowledge and experience in the law.

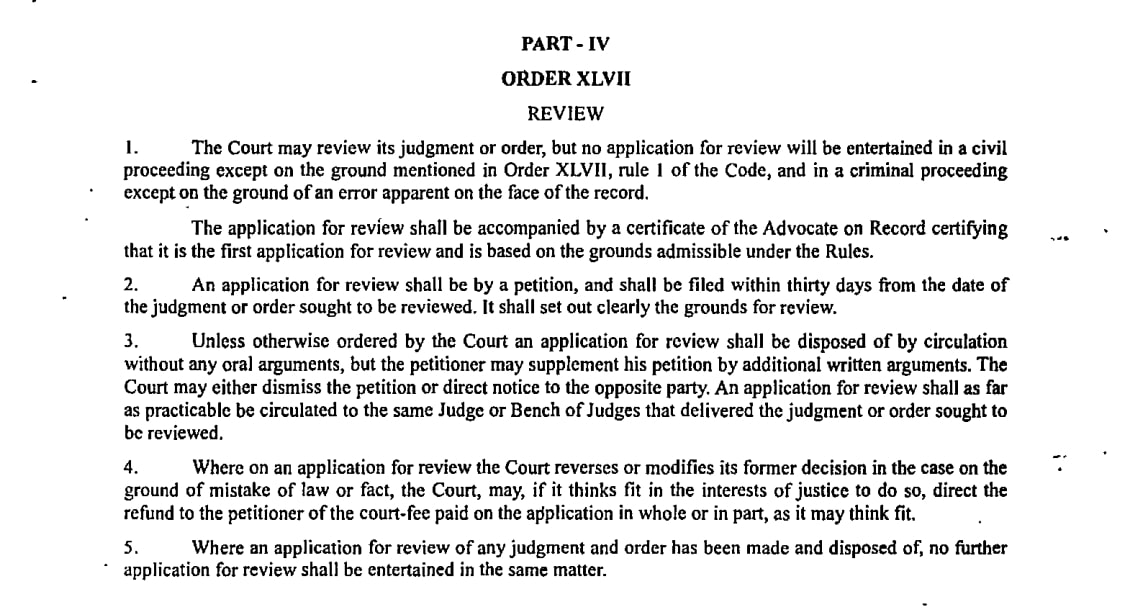

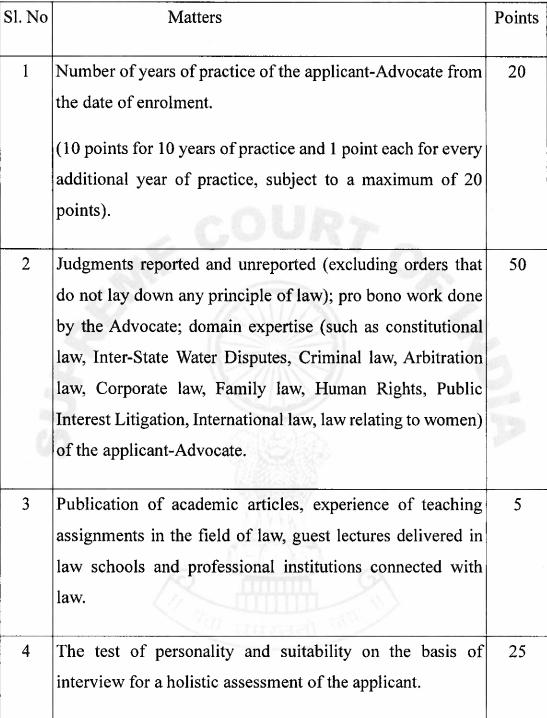

In 2017, the Supreme Court laid down elaborate guidelines on the designation of Senior Advocates to make the process objective, fair and transparent. These guidelines create a ‘Committee for Designation of Senior Advocates’ (the Committee) with the Chief Justice of India as its Chairperson and the two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, the Attorney General and a senior member of the Bar. This member is nominated by the other members of the Committee. The Committee invites applications from advocates and retired judges in January and July every year. The names that are cleared by the Committee are presented to all the judges of the Court for a final decision. Similar guidelines have been adopted by different High Courts.

Senior Advocates enjoy the ‘right to pre-audience.’ Hence, a court will hear Senior Advocates before other Advocates. However, according to Part VI of the Bar Council Rules, Senior Advocates cannot draft or file pleadings or applications or appear before the Supreme Court unless they are instructed by an Advocate-on-Record. The Rules also bar Senior Advocates from entertaining litigants directly.

Who are Advocates-on-Record?

Advocates-on-Record are the only advocates who can represent a party at the Supreme Court. Only they can file a ‘vakalatnama,’ appear or file pleadings or applications. Any other advocate who appears in a case must be instructed by an AOR.

To be appointed an AOR, a person has to be an advocate enrolled at any State Bar Council with an experience of at least 4 years. They should clear the examinations held by the Supreme Court and undergo training for a period of one year under the tutelage of another AOR.

Amicus Curiae

Who is an Amicus Curiae?

The Latin phrase ‘amicus curiae’ (plural: amici) means “a friend of the court.” An amicus curiae is a person, usually an advocate who is not representing a party in the matter before the court, appointed to assist the court. Amicus curiae are often appointed where a criminal defendant is unrepresented or in complex public interest litigation cases.

Representing the Unrepresented

An amicus curiae may be appointed if the court is of the opinion that a petitioner who has chosen to represent themselves is not fit to do so, or could do so with the help of an advocate (Order IV, Rule 1(c) of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013). The Supreme Court website also mentions that an amicus curiae must be appointed for any unrepresented accused person in a criminal matter. In civil matters, this appointment is at the discretion of the court.

Guidelines for Appointment

In a 2019 judgment, Anokhilal v State of Madhya Pradesh, the Supreme Court laid down some guidelines for the appointment of amicus curiae.

- If a matter could result in a sentence of imprisonment for life, or death, the amicus curiae would have to be an advocate with a minimum of 10 years’ experience at the Bar.

- If a High Court was confirming a death sentence, the amicus curiae would have to be a Senior Advocate.

- A minimum of seven days’ time should be provided to the amicus curiae to prepare arguments on the matter.

- The amicus curiae must be allowed to interact with the accused, whom they are representing.

Public Interest Litigation

The second type of role played by the amicus curiae arises in public interest litigation. An amicus curiae is appointed by the court to provide a ‘neutral’ opinion on the questions being considered. They could be asked to help with the case by the Court (as was done in the COVID-19 case) or after volunteering their service to the Court.

There are two kinds of public interest litigation that could warrant the appointment of an amicus curiae.

One of the types of public interest cases where amici are appointed is when the specific advocate’s technical expertise is required. Here, the court could ask the amicus curiae for their interpretation of the law under consideration. For example, in the matter regarding the suo moto powers of the National Green Tribunal, the amicus interpreted the powers of the NGT and submitted that the Tribunal does not have suo moto powers. Another example is when the Court appointed an amicus curiae in the matter of 1528 extrajudicial killings in Manipur. She was asked to collate data on 62 cases for the consideration of the court. Here, the Court did not ask the advocate to interpret the law, rather the Court asked for her assistance because of her expertise in human rights law.

The second type of public interest case in which amici are appointed are cases of great public importance, where the court needs an additional opinion in deciding the matter. Last year, the Attorney General was appointed as amicus curiae when Senior Advocate Prashant Bhushan was being tried for contempt of court. This was done at Bhushan’s counsel’s suggestion. He submitted that the AG should be heard regarding whether the matter was one that involved an important legal question: should the conduct of judges be discussed on a public platform?

Amici in public interest cases are usually senior advocates of high standing. In 2019, Senior Advocate PS Narasimha had been appointed amicus curiae in all matters concerning the Board for Cricket Control. He was asked to mediate all BCCI matters before they were heard by the Court. He has now been appointed as a Supreme Court judge.

How is the Amicus Curiae paid?

In the interest of justice and the spirit of legal aid, the fees to be paid to an amicus curiae are minimal. They are to be paid Rs. 6000/- up to the admission of the matter, and Rs. 10,000/- once the matter has been finally disposed of, or heard on the regular side.

Attorney General

The Attorney General of India is a Constitutional post

The Attorney General (AG), is considered to be the highest legal officer in the country. They are appointed by the President on the advice of the Council of Ministers. They act as the primary legal counsel for the government before the Supreme Court of India. The office of AG is a constitutional post under Article 76 of the Constitution of India and there have been 14 AGs since the Constitution came into force.

Unlike the United Kingdom, where the appointment of AG is considered ‘political’ in nature, in India the appointment is solely on the basis of professional competence. The AG of India is not a member of the Cabinet and is unaffiliated with any political party.

Who can be appointed as the AG?

The qualifications for appointment as the AG are the same as those required for a Supreme Court Judge as per Article 76(1). These qualifications as contained in Article 124(3) of the Constitution include:

-

they must be a citizen of India, who was a judge of a High Court for five years; or

-

a practising advocate at a High Court for ten years; or

-

an eminent jurist in the eyes of the President.

The AG Can be Reappointed to the Office

Although the Constitution stipulates that the AG can hold office during the ‘pleasure of the President’, their term has been fixed as 3 years in the Rules. Upon the expiration of the term, they can be reappointed for another term not exceeding 3 years. The appointment of the AG can be terminated by three months’ notice in writing by either side.

Rights, Duties and Privileges

The AG advises the Government of India in all legal matters which are referred to them by the President. Additionally, they are required to represent the Government of India in all cases in the Supreme Court of India. They are also the counsel for the Government of India in any reference made under Article 143 by the President. The Government of India may also require them to appear before any High Court regarding matters that concern the government.

The AG has the right to an audience (right to conduct legal proceedings) in all courts in India and the right to take part in proceedings of both Houses of the Parliament. They can take part in joint sittings and any parliamentary committee of which they are a member but they are not entitled to vote. The AG enjoys all the privileges which are available to a member of Parliament.

Rules that Restrict the Scope of Work of the AG

The AG is barred from representing any party except the Government of India and other bodies of the government. They are also prohibited from advising against the Government of India or a Public Sector Undertaking [PSU]. The AG cannot defend an accused person in a criminal prosecution without the permission of the government. They are not allowed to accept any appointment in any company or corporation without the permission of the government. They cannot advise any department or ministry of the Government of India unless the proposal in this regard is received through the Ministry of Law and Justice.

Relevant rules: Rules made by the President of India vide Notification, 1987

Benches of the Supreme Court

When the Supreme Court was formed in 1950, it had 8 judges including the Chief Justice of India, and all of them sat together in a single Bench to decide cases. The Constitution left it to the Parliament to increase this number as and when required. When the number of cases filed in the Court increased, the Parliament increased this maximum number from 8 in 1950 to 11 in 1956, 14 in 1960, 18 in 1978, and 26 by the year 1986. The judges could no longer sit together on a single Bench – because of the increased strength, as well as the increasing number of cases. They started sitting in smaller Benches of 2 or 3 judges for the regular cases and in larger Benches of 5 or more for cases that dealt with important questions of law as to the interpretation of the Constitution.

When the Supreme Court was formed in 1950, it had 8 judges including the Chief Justice of India, and all of them sat together in a single Bench to decide cases. The Constitution left it to the Parliament to increase this number as and when required. When the number of cases filed in the Court increased, the Parliament increased this maximum number from 8 in 1950 to 11 in 1956, 14 in 1960, 18 in 1978, and 26 by the year 1986. The judges could no longer sit together on a single Bench – because of the increased strength, as well as the increasing number of cases. They started sitting in smaller Benches of 2 or 3 judges for the regular cases and in larger Benches of 5 or more for cases that dealt with important questions of law as to the interpretation of the Constitution.During the drafting of the Constitution, B.N. Rau, Advisor to the Constituent Assembly, suggested that the Supreme Court of India should always sit as a full court. This, however, was not accepted because the Constituent Assembly was dedicated to letting the judiciary use its time in the most optimum way. Sitting in separate benches could allow them to hear more cases.

Division Benches

A Bench of 2 or 3 judges, either of a High Court or the Supreme Court, nominated by the Chief Justice is called a Division Bench. There is no provision in the Constitution regarding Division Benches, but they are formed as per Order VI of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013. A Division Bench hears regular cases of appeals, causes, and other matters on a daily basis. However, a case in which the High Court has pronounced a death sentence shall only be heard by a Bench of not less than 3 judges.

Constitution Benches

A Bench of 5 or more judges of the Supreme Court does not sit every day. As per Article 145(3) of the Constitution, a Bench of 5 or more judges is to be formed when there is a need to answer an important question of law, or the interpretation of the Constitution. This Bench is called a Constitution Bench. It is also formed on occasions when the President asks for the opinion of the Supreme Court under Article 143. A Constitution Bench also examines the verdicts and /or reasoning of smaller Benches.

Are Constitution Benches’ decisions binding on Division Benches?

There is no provision in the Constitution which says that the decision of a larger Bench of the Supreme Court has to be followed by, and is binding on a smaller Bench. But in practice, a smaller Bench is required to follow precedent, and cannot disagree with the decision of a larger Bench. In Central Board of Dawoodi Bohra v State of Maharashtra, the Supreme Court said that the smaller Benches must follow the decisions of the larger Benches, not because they are bound to do so, but because of the rule of “judicial propriety and discipline”. The court further clarified that there is a need to set precedents to make the law uniform, and therefore, it is considered improper for smaller Benches to disagree with the pronouncements of larger Benches.

In Union of India v Raghubir Singh, the then Chief Justice R. S. Pathak dismissed objections raised on referring cases decided by a three-judge Bench to a larger Bench, by a two-judge Bench. He stated that the judiciary in India not only interpreted the laws but also examined the correctness and competence of laws. He further said that it is the responsibility of the highest court of the land to give a “certain, clear, and consistent” law, and not be in disagreement among itself. The law laid down had to be correct. Although Justice Pathak listed the cases before a division Bench of three judges for re-examination, he greatly emphasised the importance of judicial discipline and precedents.

After Central Board of Dawoodi Bohra v State of Maharashtra, it is established practice that a smaller Bench, if it doubts the correctness of the decision of a larger Bench, can only refer the matter to the Chief Justice for re-examination by an even larger Bench. It cannot express its disagreement. Only a Bench of equal strength can express such a disagreement, whereupon the matter is placed before a Bench which is larger in strength than the Benches that gave differing opinions.

Causelist

What is a causelist?

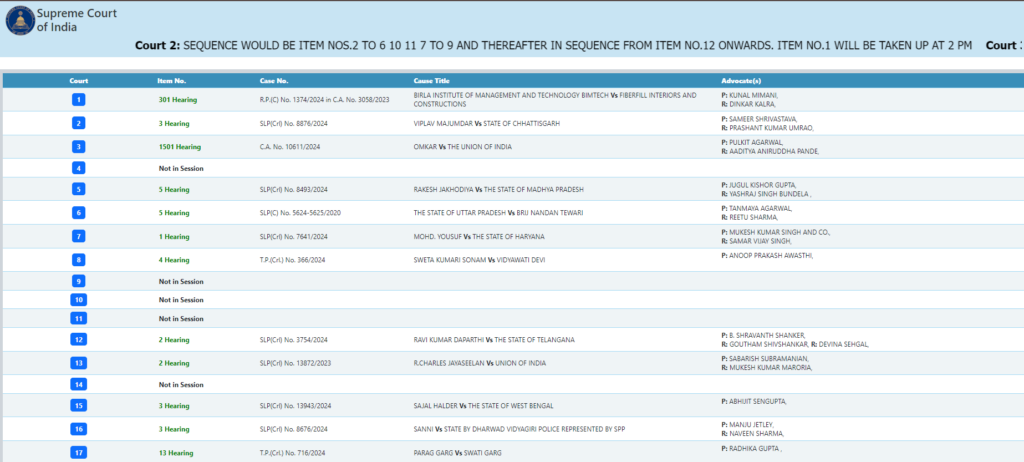

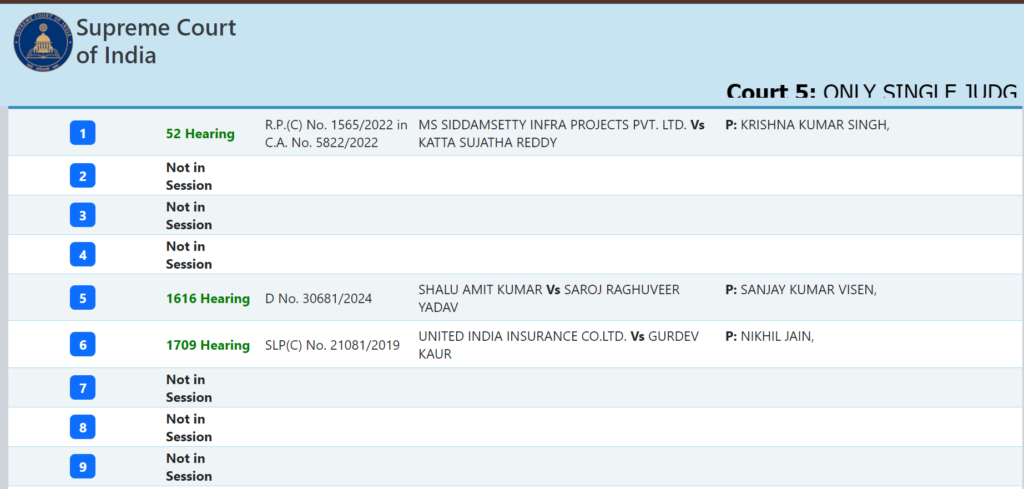

The list of cases to be heard by the Court on a particular date is known as the causelist. The causelist is the only means through which parties and lawyers are informed about when their case is going to be heard by the Court.

At the Supreme Court, the causelist is typically displayed in the precincts of the Court. Additionally, it is published on the Supreme Court’s official website the evening before a case is heard.

What does the causelist consist of?

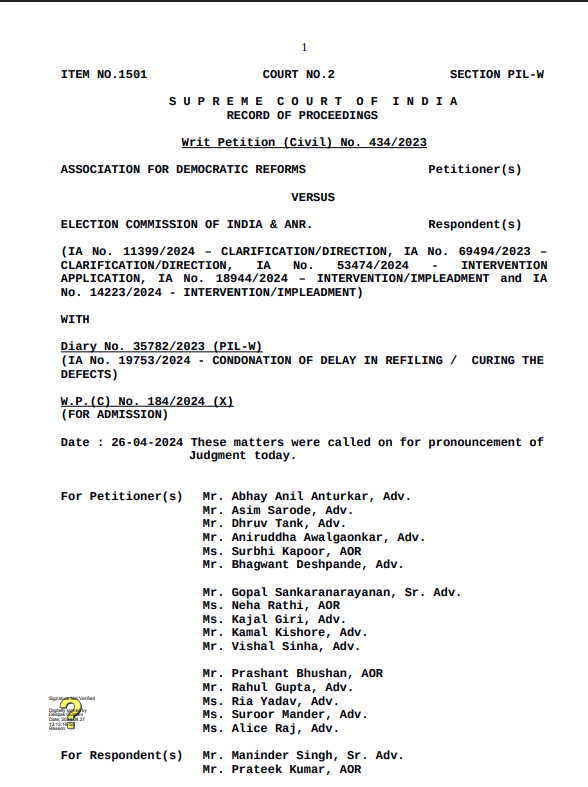

The causelist denotes the Bench hearing the case, the courtroom where the case shall be heard, the case name, the case number, the name(s) of the advocates appearing for the parties, and the serial number. The serial number, also known as the ‘item number’ of a case, denotes the order in which it will be heard by the Bench on a given day. The causelist also mentions the cases in which the Court is expected to deliver a Judgment.

What are the types of causelists?

Daily Causelist of Miscellaneous Matters: A matter that has not yet been admitted by the Court is known as a miscellaneous matter. Mondays and Fridays are ‘miscellaneous days’, reserved exclusively for the hearing of miscellaneous matters by the Court. During these proceedings, the Court decides whether to ‘admit’ the matter, allowing it to proceed to the regular hearing stage, or to dismiss it without regular hearing. The Court may hear miscellaneous matters on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays as well.

The Daily Causelist of Miscellaneous Matters shows the miscellaneous matters that the Court will hear on a particular day. For miscellaneous days, this causelist is published on Thursday of the previous week and Monday of the current week. The miscellaneous matters causelist for non-miscellaneous days (Wednesday, Thursdays, and Fridays) is issued on the Saturday of the previous week.

Daily Causelist of Regular Hearing Matters: Regular hearing matters are those that have been admitted by the Court for regular hearings. This causelist for Tuesday’s regular hearing matters is issued on the Saturday of the preceding week. For Wednesdays and Thursdays, this list is issued on the preceding day.

Weekly List: An advance list of regular hearing matters issued on the Friday of the preceding week.

Supplementary List: The matters that are not listed in the Daily Causelist are listed in the Supplementary List.

How is the causelist generated?

The Registrar of the Court draws up the causelist according to the roster created under the directions of the Chief Justice of India. Fresh admissions hearings are included in the Daily Causelist chronologically (in the order of institution) through a computerised system. There can be no changes made to the causelist once it is published.

Civil Appeals

What are Civil Appeals?

A civil appeal is filed in the Supreme Court to appeal against a judgment, order or final decree of a High Court in India.

A civil appeal can be filed if the High Court (HC) which issued the judgment grants a certificate of fitness for appeal. This must be filed within a period of 60 days from the date the certificate is granted, as per Order XIX of the Supreme Court Rules (an example can be found here).

Apart from ordinary Civil Appeals the Supreme Court has the power under Article 136 to hear any case, from any subordinate court, on appeal under its Special Leave to Appeal jurisdiction.

When can a HC issue a Certificate to Appeal?

There are two grounds on which a civil case can be taken on appeal to the Supreme Court.

The first is under Article 132 of the Constitution of India, 1950. This Article allows appeals in cases that involve a substantial question related to the interpretation of the Constitution. The Article applies to any kind of case that has been heard and decided by a High Court first.

The second ground is under Article 133. This applies specifically to civil proceedings. Such an appeal may be allowed when the HC believes that the case involves a ‘substantial question of law of general importance’ which should be decided by the Supreme Court. An appeal under this ground may also involve an interpretation of the Constitution.

In deciding whether a matter raises a ‘substantial question of law’, the Supreme Court generally considers whether the case raises questions of public importance. It may also consider the impact of the rights of the parties. In Chunilal V. Mehta and Sons Ltd. v Century Spg. & Mfg.Co.Ltd, the Supreme Court held that if the principles of law were already decided and had to be merely applied, it would not qualify as a ‘substantial question of law’.

Appeals under either of these Articles are subject to the High Court’s certification. The HC must certify that the case meets one of the two criteria. It must involves a substantial question of law or interpretation of the Constitution. Additionally, the HC must also believe that this question needs to be answered by the Supreme Court.

What Should a Civil Appeal Include?

An application for a civil appeal must include a chronological list of events leading up to the appeal. It must also specify the grounds for an appeal. It must avoid repeating facts that have already been presented before, and considered by the High Court. Instead, it should highlight the provisions of the judgment which are being challenged, and the reasons for calling these into question.

A certified copy of the concerned judgement, along with a completed Form No. 28 must be attached with the application. Form No. 28 is used for all kinds of appeals including Special Leave Petitions. So, it must be modified as appropriate for civil appeals.

The form should contain any applications for interim relief.

Constitution Bench

What is a Constitution Bench?

Article 145(3) of the Constitution of India states that a bench of a minimum of five judges must hear any case concerning “a substantial question of law” regarding the interpretation of the Constitution or cases that fall under Article 143. Article 143 grants the President the power to refer a “question of law” to the Supreme Court.

Such a bench, consisting of five or more judges which is tasked with deciding larger questions of law is called a Constitution Bench. A Constitution Bench can have five, seven and nine-judges. When the court first decides that a case requires the scrutiny of a Constitution Bench, it first refers it to a five-judge bench. Hence, five-judge benches convene more frequently compared to benches with seven or nine-judges. Further, a seven-judge bench assembles to review decisions made by a five-judge bench, and similarly, a nine-judge bench undertakes the same task for the decisions of seven-judge benches.

Since 1950, the largest number of judges on a Constitution Bench consisted of 13 judges in Kesavananda Bharati v State of Kerala (1973).

What is a “substantial question of law”?

“Substantial question of law” is not defined by the legislature or the Supreme Court. The contours of the concept have taken shape through various decisions of the Court. In 1962, Sir Chunilal V. Mehta and Sons Ltd. v Century Spg. & Mfg. Co. Ltd. laid down the test to determine a question of law as “substantial”:

- Whether the question of law is of “general public importance”

- Whether “directly and substantially affects the rights of the parties”

- The question has not been settled by the Supreme Court of India, or by the Privy Council or the Federal Court.

- There are alternative views on a single question of law.

In Boodireddy Chandraiah v Arigela Laxmi (2007), the Supreme Court defined a “substantial question of law” as something which is not settled by an existing statute or a binding precedent. Additionally, the question of law must be such that it has a “material bearing” on the final decision of a case i.e.the case’s outcome must be contingent upon the resolution of the identified “substantial question of law.”

How is a case referred to a Constitution Bench?

A Constitution Bench reference can happen in two ways.

First, under Article 143 of the Constitution of India, the President of India has the power to refer a “question of law” to the Supreme Court. This “question of law” is heard and considered by a Constitution Bench of a minimum of five-judges.

A smaller bench i.e. a division bench of two or three judges can refer a case to a Constitution Bench if they recognise a “substantial question of law” in an appeal. After the Constitution Bench settles the question, the division bench (of two or three judges) will consider the appeal on the basis of that decision.

The Chief Justice has the discretion to form a Constitution Bench and its composition. There is no discernable method using which the CJI is known to select the judges that form the bench.

Looking Ahead

On 20 September 2023, Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud expressed his intentions to make Constitution Benches a “permanent feature” of the Supreme Court. Currently, there is a backlog of 56 Constitution Bench cases across five, seven, and nine-judge matters. The decisions of these cases will have an impact on several pending cases in several high courts and lower district courts. There is also talk about splitting the Supreme Court’s function into a Constitutional Court and a Supreme Appellate Court. Many argue that these changes would expedite several cases pending due to a lack of clarity on the substantial question of law.

Contempt of Court

What is ‘Contempt of Court’?

Black’s Law Dictionary defines ‘contempt’ as “a willful disregard of the authority of a court of justice or legislative body or disobedience to its lawful orders.”

This “disregard” may include disrespect, non-cooperation and resistance towards a Court of law and misbehaviour with legal officials. Scandalising or “lowering the authority of the Court”, obstructing justice, prejudicing a court hearing are also instances of contempt. This category of contemptuous behaviour is considered criminal contempt.

Non-compliance with a court’s “judgement, decree, direction, order, writ or other process” is also considered to be contemptuous behaviour. This type of “wilful disobedience” amounts to civil contempt.

In India, the law outlining contempt is the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971 (Contempt Act).

Contempt jurisdiction of the Supreme Court

Section 23 of the Contempt Act empowers the Supreme Court and High Courts to make rules on the process of hearing and clearing contempt cases, as long as they are consistent with the Act. The Supreme Court has exercised this power through the Supreme Court Rules 2013 in a chapter titled “Rules to Regulate Proceedings for Contempt of the Supreme Court, 1975.”

The Supreme Court’s power to punish for contempt is found under Articles 129 and 142 of the Constitution of India. Article 129 says that the Supreme Court has the authority to “punish for contempt.” Additionally, Article 142, which deals with the “enforcement of decrees and orders,” of the Supreme Court, grants the Court the authority to punish parties for failure to abide by its orders and decrees.

The Contempt Rules distinguish acts of contempt committed within the Court and outside it. According to Rule 2, contemptuous acts committed in the presence of the Court can be punished immediately or on a later date.

For contemptuous acts committed outside the Court, the Supreme Court may take up the case :

- suo motu (on its own volition)

- Through a petition by the Attorney General or Solicitor General, or

- Through a petition filed by any person. Where a criminal contempt is being alleged by the private individual, the petition must be accompanied by a written consent from the Attorney General or Solicitor General.

Notable Judgements

In Supreme Court Bar Association v Union of India (1998), a five-judge Constitution Bench held that the Supreme Court cannot debar lawyers who are found guilty of contempt. This power vests only with a State Bar Council or the Bar Council of India.

In Zahira Habibullah Sheikh v State Of Gujarat (2006), the Supreme Court held the Contempt Act only stipulates punishment for contempt in High Courts. The Supreme Court has been conferred the power to make its own rules, and is only obligated to refer to the Contempt Act as a guide while exercising its own contempt jurisdiction.

In 2002 the Supreme Court was hearing contempt alleged by a private person against comments made by author Arundhati Roy. In a protest against Narmada Bachao Andolan outside the Court premises, she had remarked that the Court was trying to “silence criticism and muzzle dissent, [and] to harass and intimidate those who disagree with it.” In the In Re: Arundhati Roy (2002) judgement, Chief Justice G.B. Pattanaik and Justice R.P. Sethi clarified that constructive criticism of a judge or the judicial system does not amount to contempt if it is made in good faith and in the interest of the public.

The Supreme Court took suo moto action in a case titled In Re Prashant Bhushan & Anr (2020) and held Advocate Prashant Bhushan and Twitter India, guilty of criminal contempt on 14 August 2020. In his tweets, Bhushan had remarked that the Supreme Court played a role in the “destruction” of democracy over the past six years. He accused four preceding CJIs of facilitating it. He had also tweeted a photograph of former Chief Justice S.A. Bobde riding a motorbike owned by a political leader. Bhushan pointed out that the Chief Justice was “without a mask” and “helmet” despite keeping the Supreme Court in a “lockdown mode,” denying justice to several litigants. At the time of the tweet and the judgement, CJI Bobde was serving as Chief Justice of India. Bhushan was fined ₹1 for his statements.

In the challenge to the Electoral Bonds Scheme, a five-judge Constitution Bench was forced to threaten contempt proceedings twice. The first instance was when the State Bank of India sought for an extension of the Court’s deadline for disclosing details of bond transactions, citing certain difficulties in making the data public. Unconvinced, the Court refused and directed SBI to submit details by the next day. They threatened to initiate proceedings for civil contempt if they did not comply.

The second instance took place days later, when advocates began to “shout” in Court, demanding that their grievances over the Court’s decision be heard out of turn. When the counsel refused to stop speaking despite the Bench’s instruction to follow proper procedure to qualify for mentioning, the Court warned that they would initiate criminal contempt proceedings for obstruction of justice.

Criminal Appeals

What are criminal appeals?

A criminal appeal may be filed in the Supreme Court to appeal against a judgement, order or final decree issued by a High Court in criminal proceedings. A criminal appeal to the Supreme Court may originate in three modes:

- A criminal appeal may be filed within a period of 60 days if the High Court grants a certificate of fitness for appeal. Order XIX of the Supreme Court Rules sets out a model certificate of fitness.

- In cases where the conditions under Article 134 are met there is an automatic right of appeal irrespective of whether the High Court has granted a certificate of appeal.

- The Supreme Court under Article 136 may hear any case on appeal under its Special Leave to Appeal jurisdiction.

When can a HC issue a Certificate to Appeal?

A High Court may issue a Certificate to appeal in two circumstances. First, under Article 134A of the Constitution of India, 1950 when the matter involves a substantial question related to the interpretation of the Constitution (Article 132) or where a substantial question of criminal law may be raised (Article 134). Article 134 uses the phrase ‘fit for appeal’ which extends to substantial questions of law and not to questions of fact (Nar Singh v State of Uttar Pradesh, 1954).

When is there an Automatic Right to Appeal?

There is a second route available only to criminal cases under Article 134. This is an automatic right to appeal. Such an automatic right is available when the High Court has sentenced an accused to death. However, not all death sentences have an automatic appeal. It is only when the High Court has reversed a trial court’s acquittal, or withdrawn a case from a trial court and heard the case itself that an automatic right to appeal exists. There is no need for a certificate in such cases.

The Supreme Court has clarified that for an automatic right to appeal, it is not necessary that the High Court reversed a ‘complete acquittal’ in the trial court. For example, in Tarachand Damu Sutar v State of Maharashtra (1961), the accused was convicted of a lesser offence, but was acquitted of murder at the trial court. The High Court reversed this decision and held him guilty of murder and sentenced him to death. Here, the Supreme Court held that the convicted person was entitled to file an appeal under Article 134.

Besides this, Article 134 also gives Parliament the power to extend the scope of the Supreme Court’s criminal appellate jurisdiction. One such change took place by way of the Supreme Court (Enlargement of Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction) Act, 1970. This Act allows automatic appeals when the High Court either reverses an acquittal in, or withdraws a case from, a trial Court and then sentences the accused to ten years or more in prison.

What Should a Criminal Appeal include?

The application for a criminal appeal must include the details of the original judgment against which the appeal is being filed, including the name of the judge and the designation of the Court. It should also include details of the conviction such as the relevant provisions of law and the sentence imposed, including any fines.

The application must explain the facts of the case chronologically, the questions of law which are being raised and a list of grounds for the appeal. It may also disclose the grounds for interim relief sought while the appeal is being decided.

A criminal appeal must be filed along with a certified copy of the concerned judgement and a completed Form No. 28. Form No. 28 is used for all kinds of appeals including Special Leave Petitions. So, it must be modified as appropriate for criminal appeals.

A ‘proof of surrender’ also needs to be filed. This is a declaration that the convicted person is in custody or has surrendered after the conviction. The declaration should contain the details of the prison in which they are serving their sentence, and a certificate from a competent officer of the prison.

Curative Petitions

What is a Curative Petition?

A Curative petition is considered the last available remedy for reconsidering a judgement delivered by the Supreme Court. The curative remedy was introduced by a Constitution Bench in Rupa Ashok Hurra v Ashok Hurra (2002).

As per Rupa Ashok Hurra, the Supreme Court can only entertain a curative petition if it falls into the following criteria:

- If there was a violation of the principles of natural justice,

- If there was a question of bias against the presiding judge,

- If there was an abuse of the process of the court.

These grounds were not exhaustive. In Rupa Ashok Hurra, the Supreme Court cautioned that a curative petition should only be considered in rare circumstances to prevent frivolous litigation. The Court stated, “Curative petitions ought to be treated as a rarity rather than regular.”

Prior to the introduction of the concept of a curative petition, the last stage to reconsider a Supreme Court judgement was through a review petition. The curative remedy is an additional stage available for the parties to reconsider a judgement after a review petition is exhausted.

Procedure of Curative Petition

The procedure for entertaining a curative petition is provided under the Supreme Court Rules 2013.

- The curative petition shall declare that the grounds mentioned in the petition were dismissed in a review petition.

- A Senior Advocate should attest that the petition matches the requirements in Rupa Ashok Hurra.

- An Advocate-on-record should attest that the petition was the first and only petition filed in the case

- The curative petition should be filed within a “reasonable time” from the date of judgement or order in a review petition. The rules do not expressly define “reasonable time.”

A Bench of the three senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, and the judges who passed the judgement will consider the petition. If the majority of the judges on that Bench agree that the matter needs substantial hearings, it will be taken up by the same Bench.

The Bench also has the power to impose exemplary costs if the petition is found to be without merit and vexatious.

Notable Cases

In National Commission for Women v Bhaskar Lal Sharma (2013), a curative bench set aside a judgement which observed that “kicking your daughter-in-law” does not amount to cruelty. The National Commission for Women filed the curative petition on behalf of Monica Sharma, who had accused her husband and in-laws of cruelty. The Supreme Court held that the observations were made in a summons order against the accused person, and stated, “it was too early a stage, in our view, to take a stand as to whether any of the allegations had been established or not.” They ordered a fresh hearing.

In Union of India v Union Carbide (2023), a Constitution Bench rejected a curative petition seeking additional compensation for victims of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy. They held that it did not meet any of the grounds necessary to entertain a curative petition. The Bench viewed that allowing this curative petition would open a ‘Pandora’s box‘ stating—”We find it difficult to accept that this Court can devise a curative jurisdiction that is expansive in character”.

Display Board

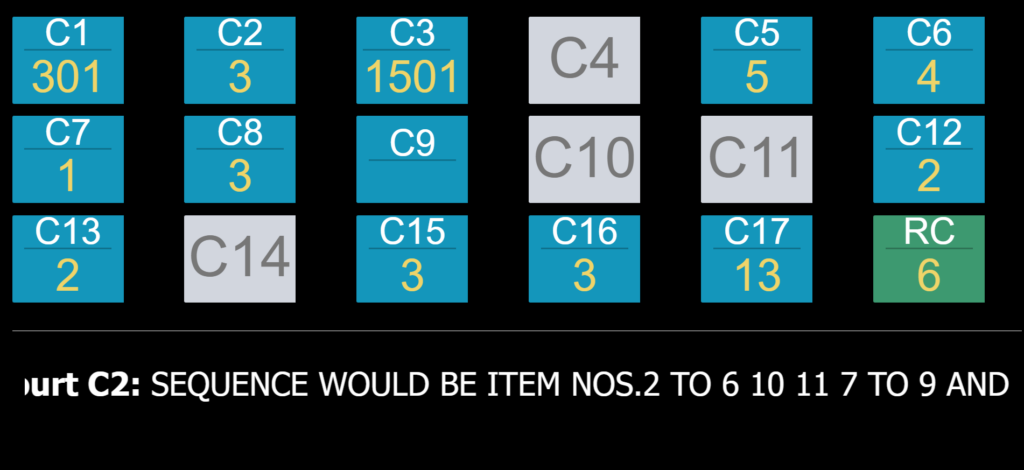

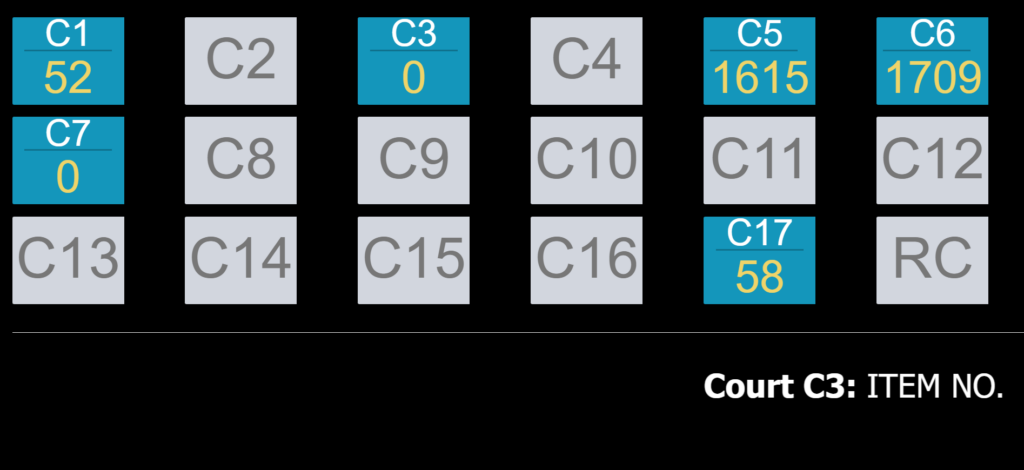

The cases scheduled to be heard in each room of the Supreme Court are listed on the daily causelist. Typically, the list includes 60-70 cases per court. To help track the order of these cases and when one is being heard, the Supreme Court website has developed a “Display Board”.

The Display Board shows the Court number and the item number of the case being heard. Item numbers are assigned according to the order of cases in the causelist. For example, if Court 1 is hearing the case listed at Item 50 in the causelist, the display board will show “C1/50”.

Practitioners and parties can use the Display Board to track their item number and assess when their case is being heard. Generally, Courts follow the order of cases in the causelist. If the sequence is altered, the Display Board reflects those alterations. Additionally, the Display Board also notifies when certain listed cases are not going to be heard by the bench.

The new Supreme Court website contains two different types of display boards:

- Display Board (as per the old Supreme Court website)

- Display Board Module (New)

The Display Board Module shows the Court Number, the Item Number, the Case Number, the name of the parties, and the counsel appearing in the case. The new module makes the case more identifiable than the previous one.

Although similar in function, both display boards differ in terms of look and feel. For instance, on the old Display Board, the courts that are no longer in session, are marked in grey. Whereas the Display Board Module writes “Not in Session” next to the Court number.

Disposal of Cases

What is Disposal?

Disposal of a case refers to its ‘exit’ from a particular court. It does not necessarily mean the end of the case as a whole.

At the Supreme Court, a case can be disposed of at four stages— the stage before admission, admission, final disposal on merit at admission and regular hearing.

1. Disposal by the Registry: The Registry can reject a petition or application after a preliminary check, before it gets admitted. A petition or application can be rejected at this stage if:

- Defects pointed out by the Registry are not rectified within due course of time (generally 28 days).

- The Registrar finds that the petition “has no reasonable cause or appears frivolous or is related to a scandalous matter.” The Registry gets this power from Order XV, Rule 5 of Supreme Court Rules, 2013. For instance, on 29 May 2024, the Registrar rejected Delhi’s Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s plea seeking an extension of the interim bail granted to him on grounds of ‘non-disclosure of reasonable cause in the petition.’

2. Disposal at Admission Stage: Once the Registry clears a petition as valid, it enters the admission stage. At this stage, a Division Bench of the Court assesses the case and can dismiss it if it does not involve ‘a substantial question of law.’

3. Final Disposal on merit at Admission Stage: When there are cases which can be admitted and disposed of within a few hours, a bench hearing the case at the admission stage can issue notice to both parties, hear the case on merits and dispose of it. It is also called a ‘Motion Hearing’. The rationale behind motion hearings is to save the Court’s time.

4. Disposal at Regular Hearing Stage: Once admitted, the case is assigned to a bench. The bench hears the case on merits and it is disposed of when the bench delivers a final judgement.

What are the types of disposal?

A case can be disposed in five ways:

- Dismissed: The Court rejects a petition at the admission stage either because it does not concern a question of law or no further hearing is required because the matter was previously adjudicated by the Court.

- Disposed: The Court rejects the prayer through the final order or judgement after hearing the matter on merits.

- Allowed: The Court accepts the petitioner’s prayer in its final order or judgement.

- Granted: The Court accepts the prayer which seeks certain permission from the court. It can be permission to grant special leave for an appeal or to alter the fine, penalty or compensation amount.

- Partly Allowed or Granted: The Court accepts certain parts of the prayer.

- Conditional Order: The Court accepts all or some of the prayers but under certain conditions. The right granted by the court is conditional upon the execution of the order of the Court.

How are cases disposed according to their registration status?

- Registered Cases: The registered cases can be either dismissed at the admission stage or disposed of after the regular hearing stage.

- Unregistered Cases: The cases waiting for approval of the Registry in general or the Registrar, in particular, can be dismissed or disposed of by the Registry for non-rectification of defect or by the Registrar. It also includes cases falling under the court’s inherent powers which are heard and then either admitted, dismissed or disposed of.

Where can we find the data about disposal?

Information relating to the number of cases disposed of by the Supreme Court can be found annually in the Supreme Court’s annual reports. On a day-to-day basis, the information is available on two major platforms:

National Judicial Data Grid: The NJDG of the Supreme Court is maintained by the Supreme Court Registry in assistance with the Department of Justice, Ministry of Law and Justice. It provides simplified data on the Supreme Court.

The Grid displays the case disposals in the past month and the ongoing year, the disposal rate in the past month and the ongoing year and divides the disposal data into civil and criminal cases.

The ‘Disposal Dashboard’ on the grid shows the disposal data for every year since 2018. It enumerates the disposal of registered and unregistered cases, the disposal of different categories of cases, the nature of disposal, the time taken for disposal, and the list of cases disposed of. All this information in data form is demarcated into civil and criminal cases with a combined final tally.

Justice Clock: It is managed entirely by the Supreme Court Registry on the website of the Supreme Court. A board-like screen displays the number of cases instituted and disposed of on that specific day, the previous day, the previous week, the ongoing year and the previous year. It also displays the Case Clearance Ratio i.e. the percentage of the number of cases disposed against the number of cases instituted during a given time frame.

How is the Chief Justice of India Appointed?

The Chief Justice of India is the highest ranking Judge at the Supreme Court. Article 124(1) of the Constitution of India, 1950 establishes the Supreme Court of India. Crucially, it adds that the SC that it must have a Chief Justice of India (CJI). The CJI is often called the ‘First among equals’ among the Judges of the SC. When a case is admitted by the Supreme Court, the CJI has the duty to assign the case to a particular Bench. The CJI decides how many judges should hear the matter, and which judges will be on the Bench. Further, the CJI leads the SC Collegium which is responsible for recommending Judges for appointments at High Courts and the Supreme Court.

The President is given the power to appoint SC Judges, including the CJI, under Article 124(2). The Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) for the appointment of SC Judges provides the steps to be taken to appoint a new CJI. The MoP states that the CJI should be the ‘senior-most Judge of the Supreme Court considered fit to hold the office’. The Union Minister for Law, Justice and Company Affairs (Law Minister) writes to the outgoing CJI, asking them to recommend a successor. After receiving the recommendation, the Law Minister forwards it to the Prime Minister of India who advises the President. Ultimately, the President decides whether to approve the recommended appointment for the next CJI.

Further, the MoP provides the procedure for the appointment of a CJI when there are doubts regarding the ‘fitness’ of the senior-most Judge at the SC besides the outgoing CJI. The President, after consulting the outgoing CJI, may consult other SC or High Court Judges ‘as they deem necessary’, as per Article 124(2), and make the appointment for CJI.

If the office of the CJI is vacant for any reason, the MoP states that the President will make an appointment using their power under Article 126 of the Constitution. During the vacancy period, before the President has made an appointment, the MoP states that the senior-most Judge of the Court will perform the duties of the CJI.

How to find a Case on the Supreme Court website?

The new Supreme Court of India website has been updated (as of 28 January 2024) with a fresh look and feel. The homepage now features all necessary functions in one place, including access to the cause list, a tool for finding case status, judgements, office reports, and the display board (used to check which case is being heard in which courtroom).

How to use the Supreme Court case page?

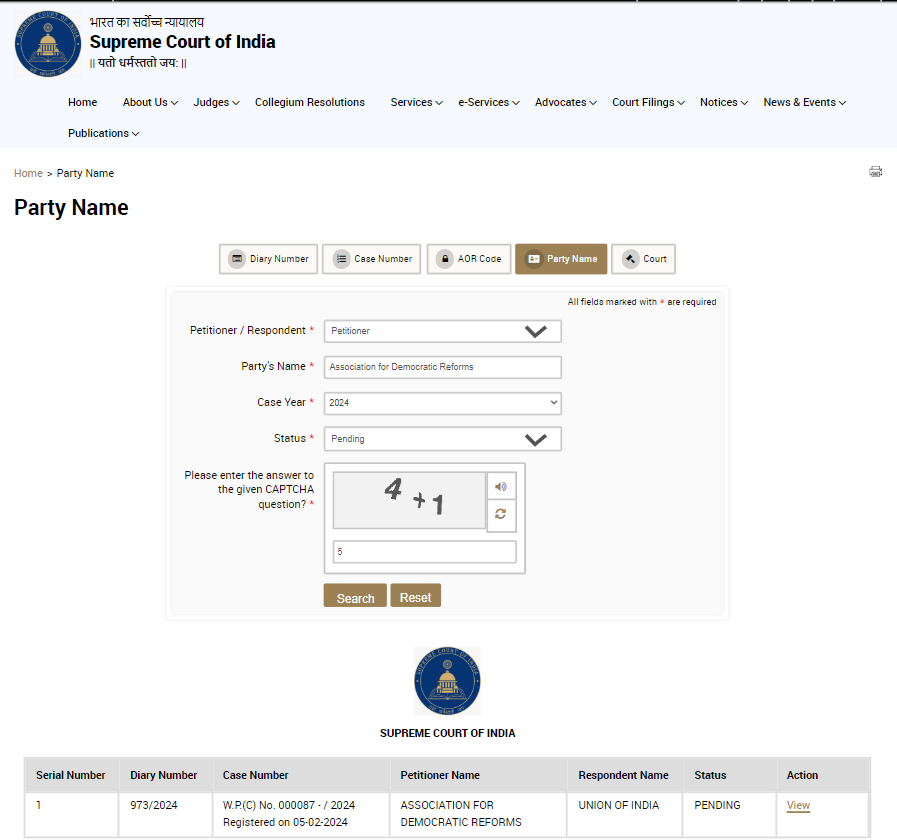

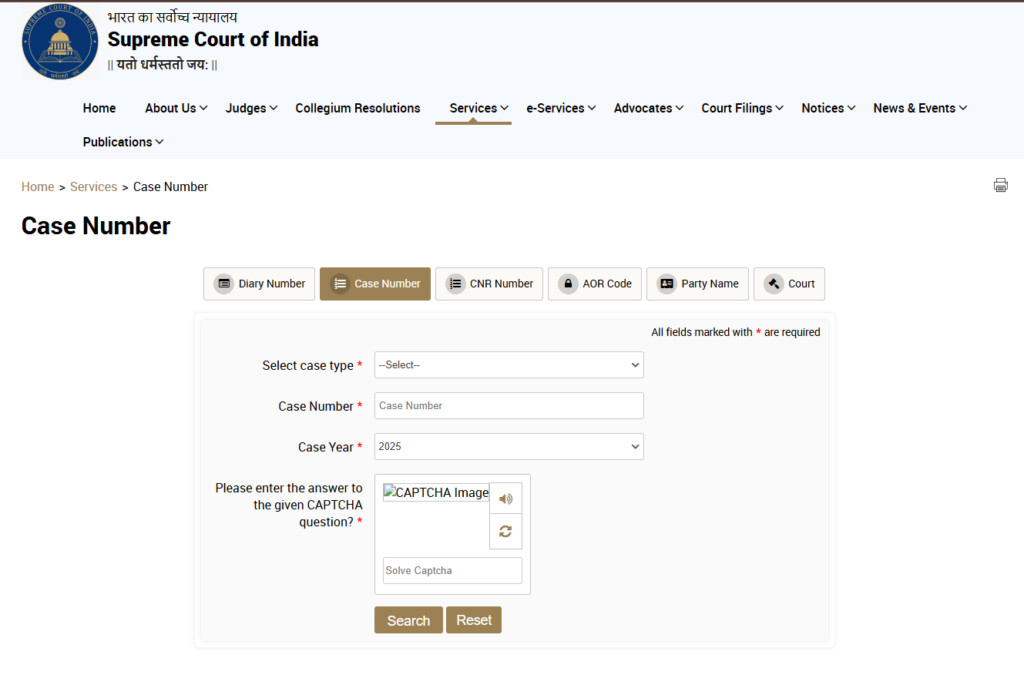

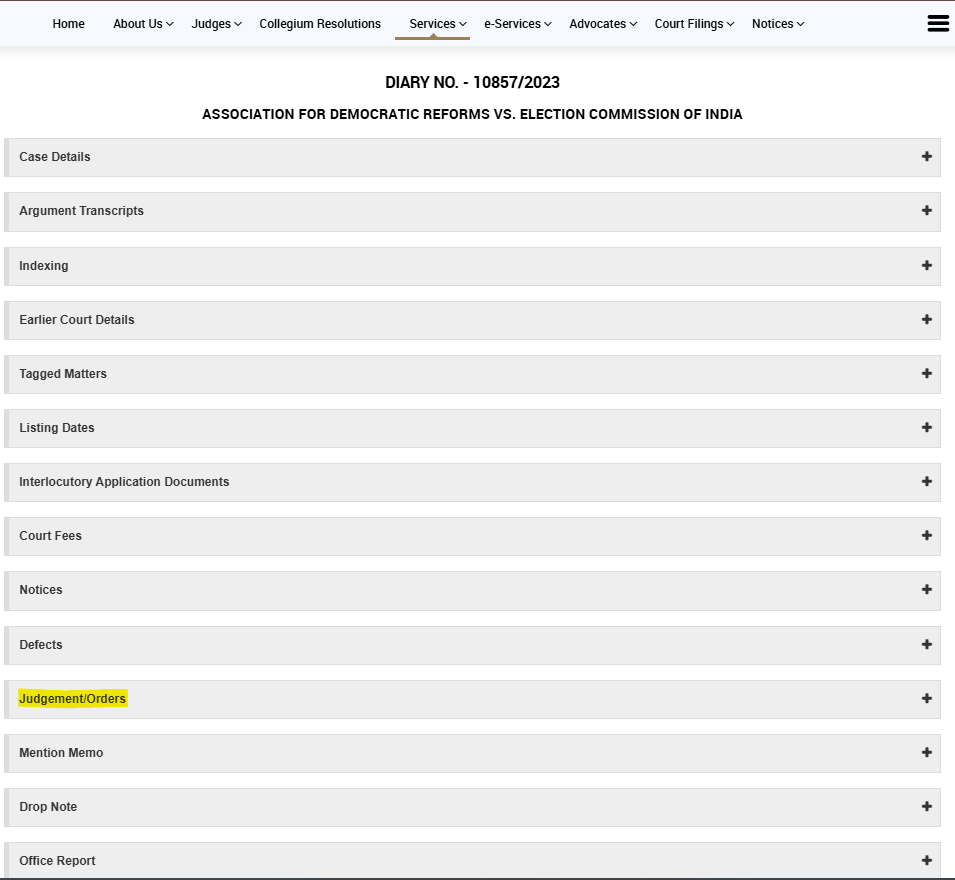

Once you click on the case status page, you will be able to access the status of a case through the following important modes: Diary Number, Case Number, AOR Code, and Party Name.

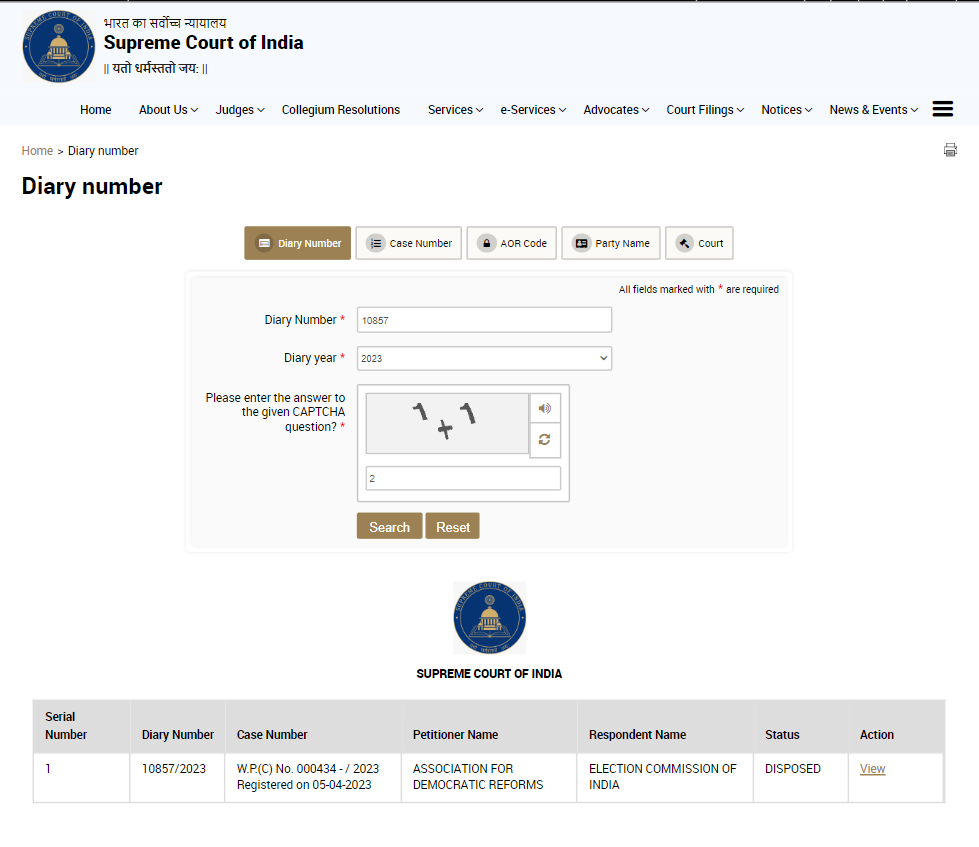

1) Diary Number: This is the number provided by the registry at the filing counter. The Diary number is useful to check the status of a case. Once you enter the diary number in the search field, the system will provide details such as the filing date, case type, current status, and listing and hearing dates (click on VIEW). Below is an example of accessing the details of a case using a diary number.

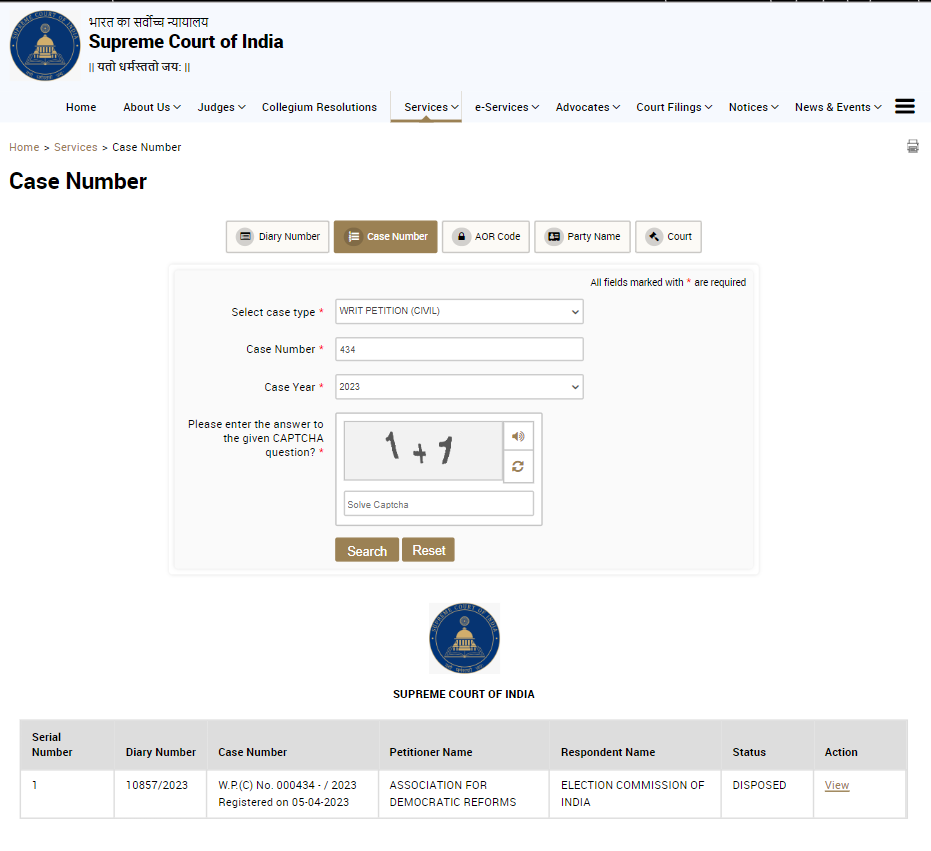

2) Case Number: This is the default selection when you click on the case status page. Select the type of case that was filed, key in the number assigned to the case, and the year it was registered by the Court. For example, if it is a writ petition, a special leave petition, a civil or criminal appeal, the user simply selects the relevant option. This will render results such as the current status of the case, dates it was listed on, and past orders given by the Court.

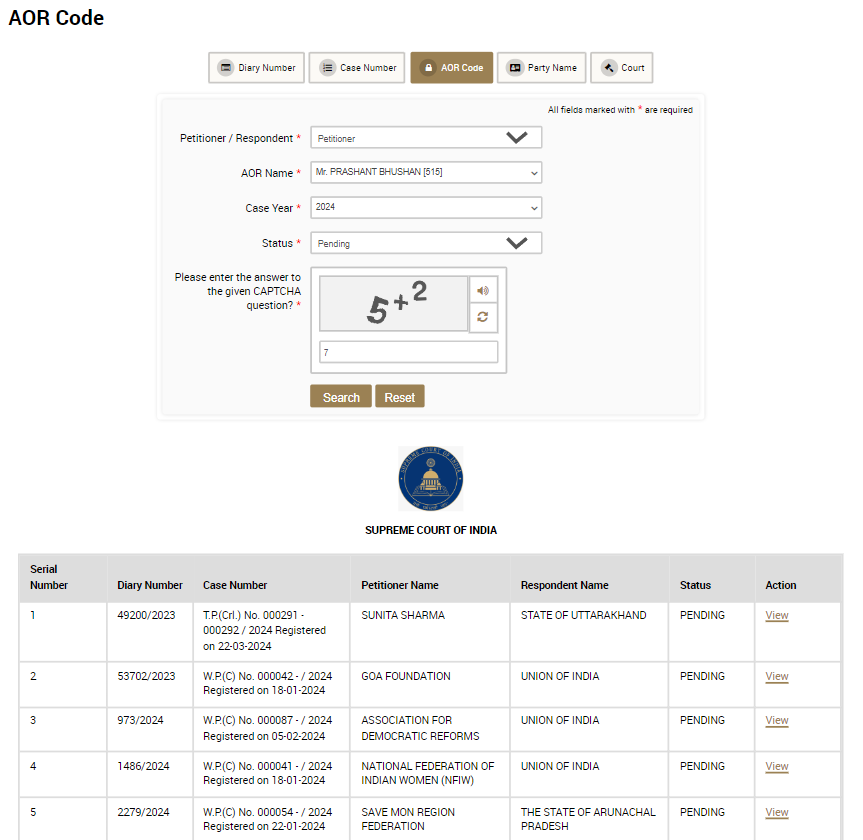

3) AOR Code: This option allows users to access case details based on the Advocate-on-Record (AOR) involved in the case. By entering the name or code of the AOR, one can retrieve information on all the cases that the AOR has filed or is representing in the Supreme Court.

4) Party Name: This option is useful for finding cases based on the names of the parties involved. Whether you are interested in a particular petitioner or respondent, you can enter the party’s name along with the year in which the case was instituted to retrieve case details.

With this, you can now access the Supreme Court website and find the cases you want! All you have to do is know basic mathematics to crack the captcha and you are all set to go exploring.

In Chambers Proceedings

In its literal sense, ”in chambers” means those dialogues and decisions which occur “in private” or in a chamber. In the context of the Court, this chamber is the judge’s office. In chamber proceedings are conducted in the absence of the media and public.

Typically, in-chamber proceedings are less time consuming than the proceedings in open court. They comprise only the judges and parties to the suit and their lawyers. In some jurisdictions, like in the United States and the United Kingdom, “in chamber” hearings are also held inside courtrooms, instead of the judge’s chamber. However, the hearing is conducted in private, involving only the parties and the courtroom is closed to the public. In jurisdictions such as in Singapore, “in chamber” proceedings also take place in the registrar’s chambers.

When are proceedings held “in chambers”?

Open court proceedings display everything about the ongoing matter to the media and public persons. But “in chamber” proceedings are, by their nature, more privately conducted. This does not mean that public interest issues are not adjudicated through “in chamber” hearings. In the Supreme Court of India, “in chamber” decisions and discussions are conducted in the following situations:

- A single-judge takes decisions “in chambers” on particular types of applications filed before the Court such as application for amendment of pleading, application for registration of Advocates-on-Record, or application to be exempted from paying court fees. The single judge “in chamber” also takes decisions on rejection of plaints, or issuing of fresh summons and notices. The judge “in chamber” further takes decisions regarding the institution of cases, particularly when the defects or errors in the filing have not been “cured.”

- Generally, review or curative petitions are heard “in chambers.” Review pleas are decided by the bench which delivered the original decision, while curative pleas are decided by the three senior-most judges of the Court, along with the judges who delivered the original decision, if they have not yet retired. In most such cases, there are no formal hearings in chambers and the petition is circulated among the judges, who then come to a decision. The Court has sometimes exercised discretion to hold such hearings in an open court.

Where do judges get the power to conduct “in chamber” proceedings?

Judges of the Supreme Court derive the power to undertake “in chamber” decisions on various types of application from the Supreme Court Rules, 2013. Rule (2) of Order V of the Rules provides an exhaustive list of 41 situations where the decision is to be taken by the judge in chambers.

Meanwhile, review power of the Court is crystallised in Article 137 of the Constitution. However, Article 137 does not mention any specific procedure to conduct review proceedings. The Court exercises discretion on the specific mode of the proceedings, whether public or “in chambers”.

The curative power of the Court is a judicial creation developed in Rupa Hurra v Ashok Hurra (1997). In rare cases, where the original judgement was “manifestly incorrect”, “palpably absurd” or “patently without jurisdiction,” curative power was exercised. But Rupa Hurra does not state how the proceedings should be conducted. Similar to its review powers, the Court has exercised discretion on whether to conduct curative proceedings in public or “in chambers”.

Institution of a Case

What is Institution?

Institution of a case refers to its ‘entry’ in a particular court. It does not necessarily mean the commencement of the hearings in the case. A petition, plaint, appeal, or application is filed by a party in person or through her advocate. A case can also be filed virtually through the Supreme Court website’s E-Filing portal. Once the case is filed, the Court’s Registry undertakes a preliminary check of the petition and the supporting documents attached to it. Post the check, the registry uploads the description of the parties and their advocates on its virtual register and generates a ‘diary number’ for the case.

The entire process of filing of petition, followed by the cognisance of the Registry at the filing counter, and then the allotment of diary number, constitutes the ‘institution of the suit.’

The President, the Union government, or any statutory tribunal can refer certain matters directly to the Supreme Court. Disputes arising from elections of President and Vice President are also decided exclusively by the Supreme Court. All such matters are referred directly to the Registrar who institutes the case.

What happens after a case is instituted?

1. Before Admission: Once a case is instituted, a Security Assistant at the Registrar’s filing counter scrutinises it for defects. If found, the defects have to be rectified within 28 days and re-filed. The rectified document is further scrutinised by a Senior Officer of the Registry. Once approved, the Security Assistant registers the case and assigns it a case number.

In case the Security Assistant is doubtful about the case’s maintainability, they may present the same to the Branch Officer. If the Branch Officer is also doubtful about maintainability, it is placed before the Registrar or a Single Judge (appointed on a timely basis by CJI ) in her Chamber who takes the final decision on the maintainability. If the case is found maintainable, it comes back to the Security Assistant for registration and assignment of case number.

2. The Admission Stage: Once registered, the case is forwarded to a specifically assigned ‘Court of Admission’ for listing. The Court of Admission is a Division Bench which decides whether to ‘admit’ the case for ‘regular hearings’ or not. These admission hearings are conducted every Monday and Friday—Miscellaneous Days of the Court. If there exists a ‘substantial question of law’, the Court admits the case.

Statutory criminal appeals (such as those involving the death penalty), automatically proceed to regular hearings.

3. The Regular Hearing Stage: If a case is admitted, it is assigned by the registry to a bench based on the Court’s ‘Roster System.’ The bench then commences regular hearings of the case.

How are instituted cases distinguished on the basis of registration status?

1. Unregistered Case: These are cases instituted at the Court but are under scrutiny of the registry or require correction of defects or whose maintainability is under consideration. They are not classified into a specific case category, or allotted a case number or listed for admission or regular hearing. These cases can be rejected and disposed of by the Registry.

2. Registered Case: These cases are instituted and registered by the Registry. The Registry categorises them based on the nature of the petition, allots a case number and lists them for admission or regular hearing.

How to navigate the data on Institution?

Information relating to the number of cases instituted by the Supreme Court can be found in the Supreme Court’s annual reports. On a day-to-day basis, the information is available on two major platforms:

National Judicial Data Grid: The NJDG is maintained by the Supreme Court Registry in assistance with the Department of Justice, Ministry of Law & Justice. This grid provides simplified data on the Institution of Cases by the Supreme Court.

The page displays the number of cases instituted in the past month and the ongoing year. It also classifies the institution data into civil and criminal cases.

The ‘Pending Dashboard’ section of the grid compares the institution and disposal data for every year since 2018. It also provides key insights into the institution of registered and unregistered cases, the institution of different categories of cases, the nature of the institution, and the list of cases instituted. All this data is classified into civil cases, criminal cases and a combined final tally.

Justice Clock: It is a virtual information board managed entirely by the Supreme Court Registry on the website of the Supreme Court.

A board-like screen displays the number of cases instituted and disposed of on that day, the previous day, the previous week, the ongoing year and the previous year. It also displays the Case Clearance Ratio i.e. the percentage of a number of cases disposed against the number of cases instituted during a given set of time frame.

Interim Orders

Judges issue interim orders during the pendency of a case. Interim orders do not decide the outcome of a case. By issuing interim orders, Judges do not adjudicate on the substantive issues raised in the petition or appeal, but instead grant immediate relief to the parties.

At the Supreme Court, one of the parties may file an ‘interlocutary application’ asking for interim relief. Prayers for interim relief may be made in both appeals and petitions before the Court. Interim relief may be in the form of a restrictive order that preserves status quo between the parties (such as halting the construction of a building on disputed land) or directing the parties to perform a specific action (such as transferring possession of property to the opposite party).

When a party ‘prays’ for interim relief, it must clearly lay out the grounds on the basis of which it is seeking such relief.

Sometimes, interim relief may be granted on an ex-parte basis. This means that the Court hears arguments only by the party praying for interim relief. In an application seeking ex-parte interim relief, the party must institute a ‘notice of motion’, stating the time and place of the application and the nature of the order sought by the party. This notice of motion must be addressed to the opposite party, and is signed by the Advocate-on-Record instituting the motion.

While separate applications for interim relief may be filed in certain cases, grounds for interim relief in Special Leave Petitions and Writ Petitions are laid out in the body of the petition.

Applications may also be made for ‘vacating’ an interim order. In such cases, the interlocutory application shall be processed within three working days from the date of filing and listed before a Bench.

Interlocutory Application

What is an Interlocutory Application?

After the institution of a case, an Interlocutory Application can be filed at the Court claiming relief before the Court delivers its final decision. Interlocutory Applications may be filed for a range of reliefs, some of which include the grant of Interim (or temporary) Relief, the vacation of a stay order, or the grant of anticipatory bail.

At the Supreme Court, no Interlocutory Application can be filed without serving a copy on the Advocate-On-Record of the opposite party. When a party files an Interlocutory Application at the Court, the Application is processed within three days of its filing. It is then listed before an appropriate Bench.

What is an Interlocutory Order?

The relief that the Court grants is delivered in the form of an ‘Interlocutory Order’. The Court issues Interlocutory Orders to prevent irreparable damage to a person or property during the pendency of proceedings. These Orders decide the intermediate or collateral matters in a case. They do not decide its outcome.

An example of an Interlocutory Order is an order by the Court to one of the parties asking them to sell perishable property (such as food items) that is the subject matter of the suit.

What is the difference between an Interlocutory Application and an Application for Interim Relief?

An application for Interim Relief is a type of Interlocutory Application. Interlocutory Applications cover a wide ambit of reliefs, out of which Interim Relief is only one type. Interlocutory Applications may be filed for relief until the suit is decided. However, Interim Relief typically lapses after a specific period of time.

Intervener

What is Intervention?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “intervention” as “ stepping into or interfering in any affair”.

In the legal context, intervention happens when a third party joins an ongoing litigation which may impact their rights in some way. The discretion to add an intervener to a case lies with the Court. The person who intervenes is called an intervener.

Legal Provisions Related to Intervenors

An application for intervention is moved, heard, and decided upon at an earlier stage of the lawsuit. The provisions about interveners are found in the Supreme Court Rules of 2013. They are as follows:

- A Single Judge sitting in chambers considers an application for rejecting or adding a third party as an intervenor.

- If the intervention is permitted, the intervenor is entitled to receive documents relied upon by the petitioners.

- The intervener is allowed to make oral submissions with the approval of the Court.

- An intervener is not entitled to pay any costs that are incidental to the Court proceedings unless directed by the Court.

Once an intervener is included in a hearing, they are considered respondents to the case.

Difference between Intervention and Impleadment

Another closely related legal term is impleadment. Just like in an intervention, even an impleadment tries to make a non-party, a part to the suit. However, there is a crucial difference between the two concepts. In an impleadment, a necessary party is added to the suit to determine its liability or remedy. On the other hand, intervention only allows the intervenor to present its concerns to the Court.

The party added through an impleadment is necessary to adjudicate the matter. Without such a party contending in the case, the remedy or liability cannot be decided. An intervenor however is not the original party to the case. Their contentions are not important to decide the issues of the case.

Who can intervene and when?

Interveners can make a motion in a civil suit. They are allowed to make oral submissions on how the remedy sought by a petitioner or the judgement would affect their rights. Interveners may include non-governmental organisations or public institutions who have an interest in the subject matter of the suit.

Intervention is not permitted in criminal cases, as these proceedings are exclusively between the accused and the prosecution.

Examples

In Supriyo @ Supriya Chakraborty & Anr. v Union of India (2023) petitioners approached the Supreme Court seeking legal recognition for sexual minorities in India. Several religious organisations and states (Gujarat, Assam, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Andhra Pradesh) who opposed non-heterosexual marriages, were admitted as intervenors in the case.

In Union of India v Union Carbide Corporation (2023), interveners from organisations representing the Bhopal Gas Tragedy victims filed an application in the Union government’s petition seeking a top-up on the original settlement granted to victims as compensation.

In In Re Prashant Bhushan (2020), the Supreme Court issued a suo motu proceedings for defamation against Advocate Prashant Bhushan. Social Activist Aruna Roy made an intervention application which was rejected by the registry on grounds of it being frivolous.

In Supreme Court Bar Association v Union of India (1998), the Supreme Court held that its contempt jurisdiction cannot entertain interveners as it is only between the Court and the contemner.

Judges

This section introduces how judges hear cases and how they are appointed to the Supreme Court.

How do judges hear cases?

In general, Supreme Court judges sit to hear cases in open court, in what are called benches. Usually benches comprise two to three judges. On occasion, the Court forms five judge benches to examine the correctness of smaller bench decisions. Likewise seven judge benches can be formed to look into a decision of a five judge bench and so on and so forth. The largest bench formed so far comprised thirteen judges in the Kesavananda Bharati case (1973).

The Court also forms benches of five or more judges to hear substantial questions of law ‘as to the interpretation of this Constitution’, as specified under Article 145(3). For example, the Kesavananda Bharati case entailed questions pertaining to the Constitution’s Basic Structure. A more contemporary example would be the Sabarimala Temple Entry dispute. The Court formed a five judge bench to interpret questions about the fundamental right to freedom of religion under Article 25 of the Constitution.

The Chief Justice of India decides which cases will be heard by which judges. In particular, the CJI selects both the composition of benches (which judges will sit together) and the cases that are assigned to each bench. This is referred to as the roster system. Aptly, the Chief Justice is called the Master of the Roster.

The ‘Master of the Roster’ Controversy and Introduction of the Subject-Wise System

In an unprecedented move, on 12 January 2018, four judges of the Supreme Court held a press conference to criticize then Chief Justice Dipak Misra. Justices Jasti Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi, Madan Lokur and Kurian Joseph’s primary complaint was that CJI Misra was assigning cases to benches arbitrarily.

They said that while the Chief Justice is the ‘Mater of the Roster’, this does not confer upon him any kind of superior administrative authority. Rather, they asserted that the Chief Justice is merely ‘the first among equals’. They explained that he is only responsible for determining the roster so as to ensure the ‘disciplined and efficient transaction of business’.

As such, they stressed that the Chief Justice can never ‘arrogate to [himself] the authority to deal with and pronounce upon matters which ought to be heard by appropriate benches’. In other words, they cautioned the Chief Justice against assigning cases to his own bench that were being (or going to be) heard by a different bench.

A month after the press conference, Chief Justice Dipak Misra responded by introducing a subject-wise roster system. His aim was to introduce a transparent, rule-bound system for assigning cases. Each bench was assigned a set of subjects and only heard matters pertaining to these subjects. For example, a Bench could be assigned labour, compensation and land acquisition matters (usually benches are assigned around ten subjects). The system came into effect on 5 February 2018.

In addition to introducing the subject-wise roster system, the Court entertained the idea of having a Collegium-like system for determining the roster. It heard a petition filed by Former Union Law Minister Shanti Bhushan requesting the Court to require the Chief Justice to consult with his/her senior most colleagues when determining the roster. Ultimately however, a Bench comprising Justices A.K. Sikri and Ashok Bhushan rejected the plea. However, it did re-affirm that the Chief Justice is only ‘the first among equals’.

Currently, the Court continues to use the subject-wise roster system. The Chief Justice of India selects the composition of benches and which types of cases they will hear. The current roster can be found here.

How are judges appointed to the Supreme Court?

Currently, the Collegium has the ultimate authority to appoint judges to the Supreme Court. The Collegium comprises the Chief Justice of India and their four senior most colleagues. Before retiring, the Chief Justice selects their successor, which by convention is the senior most sitting judge

When a vacancy arises, the Collegium convenes and recommends a name to the Union Government. Usually, this recommended person is a High Court judge. Nevertheless, lawyers with ten years of High Court experience or even distinguished jurists are eligible to be appointed. The Union reviews the recommendation and then either affirms it or asks the Collegium to reconsider. In instances of the latter, the Collegium will reconsider the name, but ultimately has the power to reiterate it. Once the Collegium reiterates a recommendation, the Union must make the appointment. The entire process is outlined in the Memorandum of Procedure.

The Collegium also has authority over High Court appointments. High Court appointments are governed by essentially the same procedure.

These procedures are intended to restrict the Union’s influence over appointments. Nevertheless, the Union can exert control over individual appointments. Consider, for example, the 2019 controversy surrounding Justice Akil Kureshi’s appointment. The controversy arose when the Union simply chose not to respond to a Collegium recommendation – neither accepting it nor asking for a reconsideration. This led the Gujarat High Court Advocates Association to file a petition in the Supreme Court, seeking Justice Kureshi’s immediate appointment. Ultimately, the Court and Union resolved the issue on the administrative side, avoiding disputing the appointment in open court. The Collegium agreed to the Union’s request to recommend Justice Kureshi as Chief Justice of the Tripura High Court, instead of the Madhya Pradesh High Court.

The Introduction of the Collegium

The Union Government originally had the final say over judicial appointments. The drafters of the Constitution had vested the President with the power to make appointments. Under Article 124, the President has control over appointments and must only consult the Chief Justice of India (and any other judges the President may deem necessary). Prior to the introduction of the Collegium, Article 124 was interpreted to mean that the President could act against the advice of the Chief Justice.

In the years leading up to Emergency, the Court became concerned that the Union was eroding the Court’s independence by making arbitrary appointments and transfers. Famously, in 1973, the Union selected Justice A.N. Ray as the Chief Justice of India, superseding three of his more senior colleagues. This was widely seen as Indira Gandhi rewarding him for dissenting in the Kesavananda Bharati case.

Following Emergency, the Court gradually wrested control from the Union over judicial appointments. In what are known as the Three Judges Cases, the Court established that primacy over appointments rested with the Chief Justice of India and their senior most colleagues.

In the First Judges Case (1981), the Court placed an onus on the President to substantially consult the Chief Justice when making appointments. Then in the Second Judges Case (1993), the Court went further and established that the Chief Justice has primacy over appointments. It read that the word ‘consultation’ in Article 124 means ‘concurrence’. Finally, in the Third Judges Case (1998), the Court clarified that the Chief Justice must consult with the four other senior most Supreme Court judges when making Supreme Court appointments.

The Union, through both its executive and legislative arms, has repeatedly challenged the Collegium system. For example, in 2014 Parliament passed the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Bill. The NJAC system was intended to replace the Collegium system. It would have comprised not only judges, but also the Union Law Minister and two eminent persons nominated by a selection committee. However, it never came into being. In 2015, the Supreme Court struck down the Act as unconstitutional, observing that it would infringe upon the independence of the judiciary.

For now, the Collegium system remains in place. While the Court itself in its NJAC judgment conceded that the system requires improvements, it appears unlikely that it will undergo major overhauls in the near future.

Judgment

What is a Judgment?

Judgments conclusively decide the outcome of a case. They are judicial opinions that explain what the case is about and how and why the Supreme Court is resolving the case.

After hearing the case, Judges of the Supreme Court pronounce the judgment in open court. Before a Judgment is pronounced, notice is given to the parties in the case and their Advocates-on-Record. A decree or order is subsequently drawn up in accordance with the Judgment.

What are the Components of a Judgment?

Typically, a Judgment contains the facts of the case, the legal questions the Court is resolving, relevant provisions of the law, an analysis of previous cases, arguments of the parties, the reasoning of the Court, and its ratio or conclusive decision. The ratio decidendi of a Judgment is the principle of reasoning that determines the outcome of a case. The observations of the Court are known as the obiter dicta.

Are Judgments of the Supreme Court Binding?

As per Article 141 of the Constitution, a Judgment of the Supreme Court is binding on all courts in India. This includes both principles of law detailed in the Judgment as well as the Court’s interpretation of any other Judgment of the Court. This is known as a system of precedent. The ratio decidendi of a Judgment is binding on all future cases where identical facts and issues are involved. The obiter dicta are not binding.

The judgment that binds the parties is known as the ‘Majority Judgment’, delivered by a majority of the Judges on the Bench. One or more Judges may deliver a ‘Dissent’ or ‘Dissenting Judgment’, where they detail their points of disagreement with the majority Judgment. It is only the Majority Decision of the Court that forms binding precedent.

Once a Judgment is delivered, it cannot be altered or added to, except in the case of clerical or arithmetic errors, or those involving accidental omissions.

Jurisprudence

What is Jurisprudence?

Jurisprudence is best defined as the philosophy of law. It deliberates on the many facets of the law, as well as the reasoning behind legal principles. Studying jurisprudence helps both judges and lawyers understand the essential principles girding a law. This allows them to discern how the application of the law affects different aspects of society—as well as when legal reform may be required.

When Did It Evolve?

Although jurisprudence—in the West—has its origins in ancient Rome and Greece, modern Western jurisprudence as we know it today largely evolved during the Enlightenment (17th century onwards).

What Are the Major Schools of Jurisprudence?

Jurisprudence is studied through the approaches laid out by various schools. Using these frameworks helps better grasp who benefits or loses from a specific law, as well as how to situate it within a specific cultural context.

Positivist School or Analytical School

The positivist school does not focus on what the law ought to be in an ideal society, but on how to best frame it given the shortcomings of society as it is. Under this school, the law is instituted by the sovereign State. The State is viewed as a necessary evil whose power is needed to facilitate the delivery of justice in an imperfect society.

Some of the major proponents of this school are Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), Thomas Erskine Holland (1835-1926), John Austin (1790-1859), John Salmond (1862-1924), H.L.A. Hart (1907-1992), and Joseph Raz (b. 1939).

Natural School

This school examines the purpose for which a law has been enacted. Under this school, the law is not viewed as part of the larger historical evolution of society or as an arbitrary regal diktat. Instead, it is understood as the product of pure human reason—and its aim is to uplift society.

Some of the major proponents of this school are Hugo Grotius (1583-1645), Immanuel Kant (1784-1804), G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831), and Ronald Dworkin (1931-2013).

Historical School

The historical school views law as the outcome of social development, steeped in changing cultural and political mores. As a result, it is primarily concerned with observing the historical evolution of laws themselves.

Some of the major proponents of this school are Montesquieu (1689-1755), Friedrich Carl von Savigny (1779-1861), and Henry Maine (1822-1888).

Sociological School

This school of thought is less concerned with the principles underlying law, and more with how the law impacts society. This school of thought seeks to balance State and individual welfare.

Some of the major proponents of this school are Auguste Comte (1798-1857), Montesquieu (1689-1755), and Herbert Spencer (1820-1903).

Realist School

The school is concerned with understanding the law as it is practised, as opposed to how it is written. the school asserts that the cultural motivations and biases of the Judge or lawyer are inseparable from their readings of the law. In short: legal realism examines human influences on the drafting and application of the law.

Some of the major proponents of this school are Karl Llewellyn (1893-1962) and Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841-1935).

Feminist School

This school is rooted in the feminist gaze—which advocates for social, political, and economic equality between the sexes. By routing its analysis through specific social categories, feminist jurisprudence genders laws otherwise thought to be neutral—even as they were largely designed by White men. A product of second-wave feminism from the 1960s, this has led to progressive legal readings of women’s rights and violence against women.