Analysis

Critical Opportunity for Structural Reform in the Supreme Court of India

Resurrecting the constitutional function has the potential to change the way the Supreme Court of India operates

On 20 September 2023, Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud announced his plans to establish Constitution Benches with varying strengths— five, seven, and nine judges—as a “permanent feature” of the Supreme Court. Subsequently, on 12 October, the Chief listed six seven-judge bench and four nine-judge bench matters for further directions.

At a time when the Supreme Court is confronted simultaneously with stiff challenges like pendency and erosion of autonomy over judicial appointments, CJI Chandrachud’s announcement has the potential to restart a conversation about structural reform of the Court’s benches.

However, the history is not encouraging—proposals to reorganise the benches of the Court based on its different kinds of jurisdiction have remained unimplemented in the last three decades.

In 1984, the 95th Law Commission Report recommended splitting the Supreme Court into two divisions: Constitutional and Legal. The split was reiterated in the 125th Law Commission Report (1988). Earlier, in 1978, Rajeev Dhavan, now a Senior Advocate, had advanced the idea of two divisions of the Supreme Court in his book The Supreme Court Under Strain: The Challenge of Arrears.

More recently, in 2019, former Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi expressed a similar view, but minimal progress was made during his tenure. By contrast, in the 74-day tenure of former Chief Justice U.U. Lalit, 25 Constitution Bench matters were listed before five-judge benches. CJI Chandrachud’s announcement builds on this recent momentum.

Constitution Bench pendency at the Supreme Court

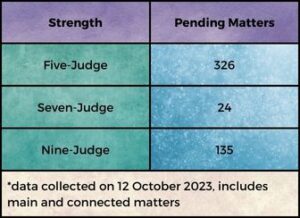

Article 145(3) states that for there to be a Constitution Bench there have to be five or more judges. According to the National Judicial Data Grid, there’s significant pendency in five, seven, and nine-judge bench matters.

Since January 2023, a five-judge bench has convened every month to adjudicate new matters (except in June when the Court was on its six-week vacation). After 6 years, on 4 October 2023, a Constitution Bench of seven judges assembled to scrutinise whether a legislator accepting bribes to influence votes in parliament and legislative assemblies enjoys immunity from prosecution. After two days of hearings, the Bench reserved judgement.

Since 1950, the Supreme Court has delivered 17 nine-judge bench decisions. The earliest nine-judge bench case pending before the Court is from 1992. Several cases concerning essential religious practices are currently pending before a nine-judge bench, namely, the excommunication of members from the Dawoodi Bohra community case, the Parsi excommunication case, and the Sabarimala review.

Splitting the Court into constitutional and appellate functions

The Constitution has established three jurisdictions for the Supreme Court: original jurisdiction through writs, appellate jurisdiction, and review jurisdiction. In 1973, the Court subsequently added a basic structure jurisdiction in Kesavananda Bharti v State of Kerala (1973). Thus, the Supreme Court is both a Constitutional Court (writ and basic structure cases) and a Court of Appeal (appellate and review cases). Currently, these two functions are not structurally institutionalised. The Court sits in benches of disparate strength as set up by the Registry under the instructions of the CJI as Master of the Roster.

Permanent constitution benches will contribute to stability and judicial consistency as cases filed under the constitutional jurisdictions will be clearly distinguishable from those filed under appellate and review jurisdiction.

In several jurisdictions, these functions are divided between two institutions. For instance, in Egypt, the Court of Cassation deals with non-constitutional appeals, and the Supreme Constitutional Court specialises in constitutional matters. In Germany, the Federal Constitutional Court and the Federal Court of Justice divide constitutional and appellate functions. Italy’s Supreme Court of Cassation serves as the top appellate court while the Constitutional Court is focused on interpreting the Constitution.

Like the Indian Supreme Court, top courts in the United States of America, Canada, and Australia perform both functions within a single institution. In India, the merging of these functions has resulted in an overdeveloped appellate function and an underdeveloped constitutional court function.

In 2021-2022, during the 16 month tenure of the former Chief Justice N.V. Ramana, no Constitution Benches were assembled. In 2021, CJI Ramana proposed that regional benches of the Supreme Court may be set up to discharge the appellate function and the Delhi Bench may focus on constitutional matters. This suggestion reveals a second structural deficit that touches upon accessibility to the Supreme Court. A 2012 study conducted by academic Nick Robinson showed that the Supreme Court hears a “disproportionate number of appeals from high courts close to Delhi.”

Can regional benches address the accessibility issue?

As a step towards making the Court more accessible, the 229th Law Commission Report (2009) recommended four regional benches to be located in Delhi, Chennai or Hyderabad, Kolkata, and Mumbai to hear non-constitutional issues. The proposal was for six judges in each region—a total of 24—to take over the appeal functions with a “Constitution Bench at Delhi working on a regular basis.” By divvying up the heavy backlog of non-constitutional cases among regional benches, the Supreme Court could “deal with constitutional issues and other cases of national importance on a day to day basis.”

Further, the Report observed that “the present situation makes the Supreme Court inaccessible to a majority of people in the country.” Former Attorney General K.K. Venugopal was motivated by the need to improve accessibility when he proposed setting up four zonal courts with 15 judges each. In a conversation with the Supreme Court Observer, Venugopal said that the government is opposed to the zonal courts proposal because “it doesn’t want to undertake a new expenditure.” Venugopal is an amicus curiae for a Constitution Bench considering a petition seeking the formation of several regional benches.

CJI Chandrachud has an opportunity to resolve this structural deficit in the Supreme Court by identifying some of the appellate benches of the court as regional benches. While the earlier proposals envisage physically relocating these Benches across the country, the digital courtrooms developed in the wake of the pandemic make this unnecessary. It’s possible that the regional skews in accessibility to the Supreme Court may be set right in one move.

A viable path forward

I’ve considered two possible structural reforms above: a separation of constitutional jurisdiction benches from appellate jurisdiction benches, and the designation of some appellate jurisdiction benches as regional benches. These reforms, taken together, have the potential to improve accessibility, reduce pendency, and clarify the judicial role and function in the Supreme Court.

If the functions of the Court are to be separated into constitutional and appellate, one route to make that happen would be a constitutional amendment. However, I believe a similar outcome can be achieved through a less cumbersome path: an amendment to the Supreme Court Rules, made by the Court under Article 145. These amendments require the assent of the President to take effect. In this economical manner with lower political barriers to reform, CJI Chandrachud has the chance to structurally reshape the Supreme Court and deliver on its promise to be a court for all Indians.

With additional reporting and research by Advay Vora.