Analysis

Section 66A: The Dead Law That Still Haunts India

In 2015, the Supreme Court declared Section 66A of the IT Act unconstitutional. In 2021, it continues to be used to arrest people.

Amendment to Outrage: the Prologue to Shreya Singhal

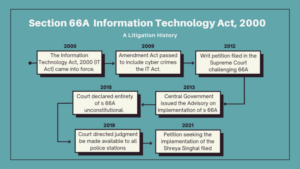

The Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act) came into force to recognise and regulate “electronic commerce”. In 2009, an Amendment Act was passed to expand the scope of the IT Act to include cyber crimes pertaining to national security, economy, public health and safety. The Amendment introduced provisions that validated electronic contracts, established data security practices for corporations to follow, and discussed provisions to combat cyber crime.

The penal provisions aimed at dealing with cyber crime included section 66A. This provision penalised anyone for “sending false and offensive messages” on any communication platform. It also made sending messages deemed annoying or inconvenient an offence. The punishment included imprisonment upto three years.

The provision and the definition of “offensive messages” were criticised to be vague. It gave the police the power to arrest individuals based on their understanding of what “offensive” or “annoying” was, without a specific and clear set of guidelines. From 2009 onwards, numerous cases were filed under s 66A, making the provision a tool for “wanton abuse” of power.

In November 2012, a woman in Maharashtra made a post on Facebook about the shutdown in Mumbai caused by Bal Thackeray’s death. Her friend liked this post. Their arrest under s 66A caused outrage and led Shreya Singhal, a law student, to file a writ petition in the Supreme Court. Other petitioners such as People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) and Common Cause also filed writ petitions challenging the constitutionality of s 66A, and were tagged together under Shreya Singhal v Union of India.

As a response to these petitions, in 2013, the Central Government issued the Advisory on Implementation of Section 66A of the Information Technology Act 2000. This advisory stated that any police officer making an arrest under s 66A had to get prior approval from an inspector above the Inspector General of Police (in metropolitan cities) or Deputy Commissioner or Superintendent of Police (at the district levels). This was further criticised to be toothless action, since interference in law enforcement by political powers was prevalent.

Understanding Reasonable Restrictions to Free Speech, in the Context of s 66A

Justices Chelameswar and Nariman opined that freedom of speech and expression have three components- discussion, advocacy and incitement. Law enforcement could intervene only when the discussion or advocacy incited public disorder or threatened the security of the State. Section 66A, however, was held to impose restrictions at the discussion and advocacy stage, gravely violating the freedom of speech and expression.

The Centre had argued that because the laws on cyber security were new and evolving, the vague and ambiguous words used in the provision was justified. That it facilitated the dynamism of the internet and its users. The Court however, referred to US Supreme Court cases where terminologies such as “sacrilegious”, “annoying conduct” and “patently offensive” were considered too vague, and were not permitted.

They also compared provisions such as section 294 and 510 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 where although words such as “annoyance” are used, they are properly defined. The justification for vagueness provided by the State was refused.

The Additional Solicitor General (ASG) argued that the scope of reasonable restriction under Article 19(2) of the Constitution of India, 1950 had to be relaxed in this instance. He referred to the global and boundaryless nature of the internet. This meant that more people had access to, and were affected by the content published there, and were more susceptible to incitement. He contended that the added measures taken to regulate the internet were justified.

The Court noted that as per Article 19(2), there had to be a clear difference between mainstream and digital media, to justify applying different rules for each. They agreed to the ASG’s claims that mainstream media and the internet were not the same, and therefore the different regulatory mechanisms devised for each was justified. However, the Court highlighted that this does not allow the government to make laws that breach the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech and expression.

Ultimately, the Court declared all of s 66A unconstitutional.

Is s 66A dead? Or is it a Legal Zombie?

Studies have noticed that despite being entirely quashed, new charges continued to be filed under s 66A. The provision has become a zombie- dead, yet staggering around Indian law enforcement with seemingly no supervision.

It is reported that as many as 1,307 cases were filed after the judgment in Shreya Singhal. (These are cases registered between October 27th 2009 and February 15th 2020 in Assam, Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal). The report notes that the number is possibly higher, as the information derived from the National Crime Records Bureau is not complete. However, the existing numbers are sufficient to show that s 66A is still in use. For instance, there was nearly one case filed every two days in Uttar Pradesh in 2015.

When this was first noticed, PUCL approached the Court seeking orders that ensured compliance with the Shreya Singhal judgment. Justices Nariman and Kishan Kaul passed an Order in February 2019. The Order suggested that copies of the Judgment be distributed to all High Courts, District Courts and to Chief Secretaries of state Governments and Union territories. They were in turn supposed to “sensitise” police personnel.

Despite this Order, PUCL noted that cases have not stopped being filed under s 66A.

What Will it Take to Implement the Supreme Court’s Order in Shreya Singhal?

PUCL filed a petition in April 2021 seeking the implementation of the Shreya Singhal judgment. PUCL sought the Court to direct orders to collect data and direct relevant bodies to seek to collect data on the pendency of cases under s 66A. They also sought the Supreme Court to issue an advisory to police stations, to not file cases under this provision. Finally, they also want the Central Government to publish information about this dead provision in all prominent newspapers in India.

The continued use of s 66A is indicative of the lack of efficient methods of communication across the key stakeholders.