Criteria for interim injunction in trademark cases

Pernod Ricard India Private Limited v Karanveer Singh Chhabra

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that rival marks in a trademark dispute must be assessed in their entirety rather than dissecting composite trademarks into isolated components.

The appellant, Pernod Ricard India Pvt. Ltd. had sought a permanent injunction restraining the respondent, Karanveer Chhabra, on the ground that his brand “London Pride”...

Case Details

Judgement Date: 14 August 2025

Citations: 2025 INSC 981 | 2025 SCO.LR 8(3)[14]

Bench: J.B. Pardiwala J, R. Mahadevan J

Keyphrases: Keywords/phrases: Trade Marks Act, 1999 - infringement - registration - deceptively similar - passing off - likelihood of confusion.

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

MAHADEVAN J.

1. INTRODUCTION

1. The Law of trademarks has been aptly described by Justice Frankfurter of the United States Supreme Court in the following words:

“The protection of trademarks is the law’s recognition of the psychological function of symbols. If it is true that we live by symbols, it is no less true that we purchase goods by them. A trademark is a merchandising shortcut which induces a purchaser to select what he wants, or what he has been led to believe he wants. The owner of a trademark exploits this human propensity by making every human effort to impregnate the atmosphere of the market with the drawing power of a congenial symbol. Whatever the means employed, the aim is the same – to convey through the mark, in the minds of potential customers, the desirability of the commodity upon which it appears. Once this is attained, the trademark owner has something of value. If another poaches upon the commercial magnetism of the symbol he has created, the owner can obtain legal redress”.

– Mishawaka Rubber and Woolen Manufacturing Co. v. S.S. Kresge Co.1

2. Trademarks are central to the identity, survival, and growth of any business operating in a competitive commercial environment. They enable enterprises to establish consumer trust and preserve the goodwill built over time through substantial investments in quality, service, and brand visibility. For consumers, trademarks serve as indicators of the source and consistent quality of goods or services across different providers, thereby enabling them to make informed choices, which may, at a minimum, affect taste and preference, and at a maximum, impact their health and well-being. It is, therefore, imperative that intellectual property rights are robustly protected against infringing entities that seek to unfairly capitalize on another’s goodwill, to the detriment of both the rightful owner and the end consumer.

3. At the heart of trademark law lies the foundational principle that there must be no likelihood of confusion in the mind of the average consumer. In cases involving composite marks, it is not necessary that the impugned mark replicate the original in its entirety; even partial imitation may amount to infringement or passing off if it evokes an association with the registered or prior-used mark in the consumer’s mind.

4. However, the application of this principle is nuanced. Courts are not expected to adopt a mechanical, side-by-side comparison of the marks. Rather, judicial scrutiny is guided by interpretative doctrines such as the anti-dissection rule and the doctrine of the dominant mark, inter alia, other well-established Although these principles are frequently applied in tandem, they do not always align perfectly, and courts have differed in their application depending on the specific facts and context of each case.

5. The present case offers an opportunity for this Court to clarify the appropriate analytical framework for evaluating competing While the anti-dissection rule – which requires the mark to be considered as a whole – has statutory foundation under the Trade Marks Act, 1999, the doctrine of the dominant mark is a judicially evolved principle, aimed at identifying the essential or memorable component of a mark that is likely to influence consumer perception. The purpose of this doctrine is to determine whether the impugned mark creates a deceptive association in the minds of consumers, thereby enabling the defendant to unjustly benefit from the plaintiff’s established reputation. This analysis is guided by the perspective of an average consumer with imperfect recollection, who is not expected to retain or compare marks with exact precision.

II. FACTUAL MATRIX

6. This appeal arises from the judgment dated 11.2023 passed by the High Court of Madhya Pradesh at Indore2 in Misc. Appeal No. 232 of 2021, whereby the High Court dismissed the appellants’ challenge to the order dated 26.11.2020 passed by the Commercial Court (District Judge Level), Indore3 in Case No. COMMS 3 of 2020 and IA No.01 of 2020.

7. By the order dated 26.11.2020, the Commercial Court rejected the application filed by the appellants under Order XXXIX Rules 1 and 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure4. For ease of reference, the reliefs sought in the interlocutory application are reproduced below:

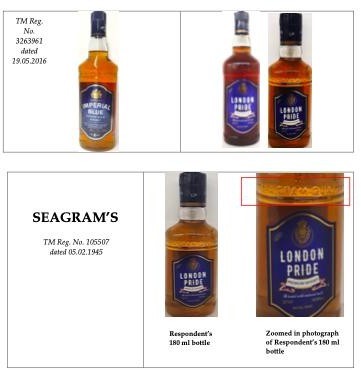

“… to grant an order of interim injunction restraining the Defendant, its proprietors, partners as the case may be, assigns in business, sister concerns, associates, agents, dealers, distributors, stockists, etc. from manufacturing, selling, offering for sale, advertising in any manner including on the internet, directly or indirectly dealing in whisky or any alcoholic or non-alcoholic beverages under the trade mark LONDON PRIDE and/or label and/or packaging and/or any other label/packaging and/or trade mark that may be identical/deceptively similar to IMPERIAL BLUE label or packaging and/or deceptively similar to the trade mark BLENDERS PRIDE and/or SEAGRAM’S amounting to infringement of Plaintiffs’ trademark registrations and/or copyright and/or passing off and/or unfair competition.”

“… in view of the facts and circumstances of the present case and in the interest of justice and the public interest, an ex parte ad interim injunction in the aforementioned terms may kindly be passed in favour of the Plaintiffs / Applicants and against the Defendant.”

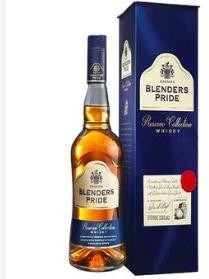

8. According to the appellants, they are engaged in the manufacture and distribution of wines, liquors, and They sell whisky under the brand names ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ and ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’, both of which are registered trademarks. The appellants also hold a registered trademark for ‘SEAGRAM’S’, which serves as the house mark of Appellant No.1, and is used both in India and internationally across various product lines.

9. On 05.02.1945, the appellants’ predecessor , Seagram Company Limited obtained registration of the trademark SEAGRAM’S vide Registration No. 105507 in Class 33, in respect of “Whisky”. Later, on 25.03.1994, registration of the trademark ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ was obtained vide Registration No. 623365 in Class 33, covering “Wines, Spirits and Liqueurs”. The trademark ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ was coined and adopted by the appellants’ predecessor, and has been in extensive worldwide use since 1973 for whisky products.

10. In 1995, ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ whisky was launched in India, and achieved an annual turnover exceeding INR 1,700 Crores for the financial year 2019-20. In 1997, the appellants’ predecessor launched whisky under the trademark ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ in On 28.06.2016, they secured registration of the ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ device, vide Registration No. 3296387 in Class 33, for “Alcoholic beverages, except beers”, followed by Registration No. 3327621 on 03.08.2016 for the same mark in the same class. The brand ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ achieved an annual turnover exceeding INR 2,700 Crores for the financial year 2018-19. Both brands today enjoy formidable goodwill and reputation, domestically and internationally.

11. In May 2019, the appellants became aware that the respondent has been marketing whisky under the mark ‘LONDON PRIDE’, using packaging that was deceptively similar to that of the The mark adopted by the respondent was not only phonetically and visually similar to ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’, but also copied the colour combination, get-up and trade dress of ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ label. Further, the respondent used ‘SEAGRAM’S’ embossed bottles of the appellants’ mark ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’, for the sale of its LONDON PRIDE whisky, which also amounts to an infringement of the appellants’ registered SEAGRAM’S trademark.

12. Aggrieved by the respondent’s actions, the appellants instituted Civil Suit No. 3 of 2020 before the Commercial Court, seeking a decree of permanent injunction restraining the respondent from trademark infringement, passing off, copyright violation, and also prayed for reliefs, such as, rendition of accounts, damages, and delivery up of infringing material. An application under Order XXXIX Rules 1 and 2 CPC, was also filed seeking an interim injunction.

13. By order dated 26.11.2020, the Commercial Court dismissed the interim injunction Challenging the same, the appellants approached the High Court by filing Misc. Appeal No. 232 of 2021, which was also dismissed vide judgment dated 03.11.2023, which is impugned in the present appeal.

III. CONTENTIONS OF THE PARTIES

14. Assailing the judgment passed by the High Court, the learned Senior Counsel for the appellants made the following submissions:

14.1 The present case involves elements of both trademark infringement and passing The respondent has dishonestly adopted trademarks deceptively similar to the appellants’ well-known and registered marks – ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’, ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’, and ‘SEAGRAM’S’ – used for whisky, which enjoy significant commercial reputation in India and internationally.

14.2 The appellants’ trademarks are duly registered and protected under Sections 28 and 29 of the Trade Marks Act, ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ has been in continuous use since 1995, with annual sales exceeding INR 1,700 Crores; ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ has been in use since 1997, with annual sales exceeding INR 2,700 Crores. In contrast, the respondent has only a pending application for the mark ‘LONDON PRIDE’ and has failed to justify its adoption of a deceptively similar mark.

14.3 The imitation of two established brands – ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ and ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ – by the respondent is neither coincidental nor innocent; it is a deliberate and dishonest attempt to misappropriate the appellants’ goodwill and reputation, thereby creating confusion or association with the appellants’ goods. This conduct constitutes both trademark infringement and passing off.

14.4 The Appellate Court failed to apply the test of deceptive similarity laid down by this Court in Kaviraj Pandit Durga Dutt Sharma v. Navaratna Pharmaceutical Laboratories.5, where it was held that once the essential features of a registered mark are copied, differences in get-up, packaging, or additional writing are immaterial. Similarly, in Amritdhara Pharmacy v. Satyadeo Gupta.6 this Court held that marks must be compared as a whole, without dissecting or excluding any part. The Appellate Court erroneously dissected the mark ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ and compared “BLENDERS” with “LONDON”, ignoring the distinctive and dominant component “PRIDE” – thus violating both the anti- dissection rule and the doctrine of overall similarity.

14.5 In an infringement analysis, the test is whether there is a likelihood of confusion or association in the mind of the public. This is a matter for judicial determination and not dependent on testimonial evidence. The law protects against the likelihood of confusion itself; there is no requirement to prove actual deception or damage. Trademarks are remembered by their overall commercial impression, and even minor variations may be perceived by consumers as brand extensions or sub-brands.

14.6 In the present case, the composite mark ‘LONDON PRIDE’ is deceptively similar to the registered word mark ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’. Both are used for identical goods – Indian Made Foreign Liquor (IMFL Whisky) – and are sold through the same trade The term ‘PRIDE’ which is neither generic nor descriptive in the context of alcoholic beverages, forms the essential and dominant part of the appellants’ mark. The respondent’s use of this term, combined with another descriptive term, results in an overall similarity that is likely to mislead an average consumer with imperfect recollection.

14.7 The label and packaging of ‘LONDON PRIDE’ constitute a colourable imitation of the registered trademarks associated with ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’, including the label, packaging, and bottle design. Despite acknowledging the principle of overall comparison, the Appellate Court erred by dissecting individual elements rather than assessing the overall visual impression created by the competing marks.

14.8 The Appellate Court placed undue emphasis on the dissimilarity between the word marks ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ and ‘LONDON PRIDE’ while overlooking the visual similarities in colour scheme, layout, and overall packaging. It is well settled that the use of a deceptively similar logo alone can amount to infringement of a registered device mark.

14.9 The Appellate Court erred in applying Sections 15(1) and 17(2) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, despite the appellants not claiming exclusive rights over the word ‘PRIDE’ per se, but only over the composite mark ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ as a whole, protected under Section 17(1). The finding that ‘PRIDE’ is publici juris, is flawed, as the respondent produced no evidence of actual or widespread use in the trade. Mere entries in the Trademark Register are legally insufficient, as held in Corn Products Refining Co. v. Shangrila Food Products7, and National Bell Co. v. Metal Goods Manufacturing Co.8.

14.10 The Courts below erroneously relied on the overruled decision in M.Dychem v. Cadbury India Ltd9, which emphasized dissimilarities in marks. The binding decision in Cadila Healthcare Ltd. v. Cadila Pharmaceuticals Ltd.10requires an assessment of overall similarity from the perspective of an average consumer with imperfect recollection.

14.11 Reliance was placed on V. Venugopal v. Ushodaya Enterprises11, Midas Hygiene Industries (P) Ltd v. Sudhir Bhatia12, and Heinz Italia v. Dabur India Ltd13, which held that in cases of dishonest adoption, injunctive relief must follow in order to uphold commercial integrity and protect consumer interest.

14.12 The Appellate Court wrongly presumed that consumers of IMFL whisky are discerning and literate, thereby ruling out the likelihood of confusion. However, the test of imperfect recollection applies regardless of a consumer’s education or economic In Cadila Health Care ltd v. Cadila Pharmaceuticals Ltd (supra), this Court affirmed that similarity between marks must be assessed from the perspective of an average consumer with imperfect recollection.

14.13 The respondent’s reliance on Khoday Distilleries Ltd v. Scotch Whisky Association14 is That decision involved a claim that the use of the term “SCOT” in the mark ‘PETER SCOT’ might mislead consumers into believing the product was Scotch whisky. The Court held that such consumers were discerning, but the context was specific to origin misrepresentation. The present case involves not the geographic origin of whisky, but deceptive similarity between brands. Moreover, Khoday Distilleries was not a case of trade mark infringement or passing off, but one concerning cancellation of registration under Section 9 of the Trade Marks Act, and is therefore inapplicable.

14.14 The continuous use of SEAGRAM’S embossed bottles by the respondent constitutes an infringement of the appellants’ registered word mark. However, the Appellate Court failed to return any finding on this crucial issue.

14.15 Reference was made to the concept of “Injurious association”, wherein the similarity of brands leads consumers to associate the defendant’s product with that of the plaintiff, thereby misappropriating the plaintiff’s goodwill. Such misappropriation causes irreparable harm – greater than mere monetary loss – because it undermines the brand identity and reputation built over decades. The structural similarity between ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’ and ‘LONDON PRIDE’, is likely to create an assumption that the two originate from the same source or that one is a variant of the other. Such mis-association is actionable and warrants injunctive relief

14.16 “Initial interest confusion” arises, where consumers are initially drawn to a product due to its similar branding, even if they realise prior to purchase that it is not the original. Courts have held that such conduct still constitutes misappropriation of goodwill. This principle is directly applicable to the present case. In this regard, reliance was placed on Baker Hughes Ltd v. Hiroo Khushalani15.

14.17 The appellants have established a prima facie case of both infringement and passing Their marks have been in continuous and extensive use for over three decades, and enjoy substantial goodwill. In contrast, the respondent entered the market only in 2018 and lacks any statutory or proprietary rights.

14.18 Accordingly, the impugned judgment dated 11.2023 is liable to be set aside, and that the appellants are entitled to interim injunction to protect their statutory and proprietary rights, and to restrain the respondent from continuing its infringing and unlawful conduct.

15. Per contra, the learned Senior Counsel for the Respondent submitted that the respondent is the proprietor of the trademark ‘LONDON PRIDE’ and all associated intellectual property. The respondent has been manufacturing and marketing liquor under the said brand name in the State of Madhya Pradesh. It was submitted that the respondent is the sole applicant for registration of the mark ‘LONDON PRIDE’, and no other party has ever sought registration under the same or similar name. Accordingly, the respondent claims exclusive rights over the mark ‘LONDON PRIDE’, including its distinctive elements and the goodwill attached thereto. It was further contended that the respondent’s mark is entirely dissimilar in name, appearance, and composition from any of the appellants’ earlier registered trademarks. The brand ‘LONDON PRIDE’ is also registered with the Excise Department of Madha According to the learned counsel, there exists no visual, phonetic, or structural similarity between their mark and those of the appellants. The appellants, therefore, lack a prima facie case, and the elements of irreparable harm and balance of convenience are also not in their favour. However, the factual assertions concerning the appellants’ trademarks, their registration status, and usage were not disputed.

15.1 Learned Senior Counsel further contended that the label used by the appellants for their products under the trademark ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’ and the label of the respondent’s product sold under ‘LONDON PRIDE’ are entirely distinct, with no elements of visual or conceptual overlap. It was submitted that there is no deceptive similarity between the labels that could lead to confusion in the minds of consumers.

15.2 It was additionally, submitted that the impugned order represents a proper and lawful exercise of jurisdiction by the Commercial Court, which thoroughly evaluated the marks and packaging of both parties before arriving at its conclusion. A holistic comparison of the trademarks and packaging reveals that the two products are clearly The goods of both parties are sold in sealed boxes, not loose, and the boxes themselves are visually distinct. The colour scheme, typography, logos and other graphical elements are markedly different. It was contended that both the essential features and the overall visual impression of the competing marks are dissimilar.

15.3 Learned Senior Counsel also submitted that to obtain a temporary injunction, the appellants were required to establish actual damage or the likelihood of irreparable harm, which they failed to do. The mere existence of a prima facie case is insufficient in law. It must also be shown that the appellants would suffer irreparable injury that could not be compensated in monetary terms, which is not the case herein.

15.4 Ultimately, it was submitted that the appellants had failed to demonstrate the essential requirements for grant of interim relief – namely, a prima facie case, balance of convenience, and irreparable harm. The Courts below, having rightly assessed the factual and legal issues, rejected the prayer for temporary Thus, no grounds for interference by this Court in appellate jurisdiction are made out by the appellants.

IV. ISSUE FOR CONSIDERATION

16. We have heard the submissions made by the learned Senior Counsel appearing for both parties and carefully perused the materials available on record.

17. The question that arises for consideration in the present appeal is whether the appellants are entitled to the grant of an interim injunction restraining the respondent from using the impugned trademark, get-up, and trade dress – including the packaging – of ‘LONDON PRIDE’ on the ground that such use amounts to infringement and/or imitation of the appellants’ registered trademarks, namely, ‘BLENDERS PRIDE’, ‘IMPERIAL BLUE’, and ‘SEAGRAM’S’.

V. STATUTORY FRAMEWORK

18. The present dispute directly invokes the statutory protections available under the Trade Marks Act, 1999, particularly in relation to trademark infringement and deceptive similarity. The relevant provisions are extracted and summarized below:

“2. Definitions and interpretation. – (1) In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires, –

(h) “deceptively similar”.— A mark shall be deemed to be deceptively similar to another mark if it so nearly resembles that other mark as to be likely to deceive or cause confusion;

(m) “mark” includes a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter, numeral, shape of goods, packaging or combination of colours or any combination thereof;

(q) “package” includes any case, box, container, covering, folder, receptacle, vessel, casket, bottle, wrapper, label, band, ticket, reel, frame, capsule, cap, lid, stopper and cork;

(v) “registered proprietor”, in relation to a trade mark, means the person for the time being entered in the register as proprietor of the trade mark;

(w) “registered trade mark” means a trade mark which is actually on the register and remaining in force;

(zb) “trade mark” means a mark capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others and may include shape of goods, their packaging and combination of colours; and—

(i) in relation to Chapter XII (other than section 107), a registered trade mark or a mark used in relation to goods or services for the purpose of indicating or so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods or services, as the case may be, and some person having the right as proprietor to use the mark; and

(ii) in relation to other provisions of this Act, a mark used or proposed to be used in relation to goods or services for the purpose of indicating or so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods or services, as the case may be, and some person having the right, either as proprietor or by way of permitted user, to use the mark whether with or without any indication of the identity of that person, and includes a certification trade mark or collective mark;

9. Absolute grounds for refusal of —(1) The trade marks—

(a) which are devoid of any distinctive character, that is to say, not capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of another person;

(b) which consist exclusively of marks or indications which may serve in trade to designate the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, values, geographical origin or the time of production of the goods or rendering of the service or other characteristics of the goods or service;

(c) which consist exclusively of marks or indications which have become customary in the current language or in the bona fide and established practices of the trade,

shall not be registered:

Provided that a trade mark shall not be refused registration if before the date of application for registration it has acquired a distinctive character as a result of the use made of it or is a well-known trade mark.

11. Relative grounds for refusal of —(1) Save as provided in section 12, a trade mark shall not be registered if, because of—

(a) its identity with an earlier trade mark and similarity of goods or services covered by the trade mark; or

(b) its similarity to an earlier trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by the trade mark,

there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public, which includes the likelihood of association with the earlier trade mark.

(2) A trade mark which—

(a) is identical with or similar to an earlier trade mark; and

(b) is to be registered for goods or services which are not similar to those for which the earlier trade mark is registered in the name of a different proprietor, shall not be registered if or to the extent the earlier trade mark is a well-known trade mark in India and the use of the later mark without due cause would take unfair advantage of or be detrimental to the distinctive character or repute of the earlier trade mark.

(3) A trade mark shall not be registered if, or to the extent that, its use in India is liable to be prevented—

(a) by virtue of any law in particular the law of passing off protecting an unregistered trade mark used in the course of trade; or

(b) by virtue of law of

(4) Nothing in this section shall prevent the registration of a trade mark where the proprietor of the earlier trade mark or other earlier right consents to the registration, and in such case the Registrar may register the mark under special circumstances under section 12.

Explanation.—For the purposes of this section, earlier trade mark means— [(a) a registered trade mark or an application under section 18 bearing an earlier date of filing or an international registration referred to in section 36E or convention application referred to in section 154 which has a date of application earlier than that of the trade mark in question, taking account, where appropriate, of the priorities claimed in respect of the trade marks;] (b) a trade mark which, on the date of the application for registration of the trade mark in question, or where appropriate, of the priority claimed in respect of the application, was entitled to protection as a well-known trade mark.

(5) A trade mark shall not be refused registration on the grounds specified in sub- sections (2) and (3), unless objection on any one or more of those grounds is raised in opposition proceedings by the proprietor of the earlier trade mark.

(6) The Registrar shall, while determining whether a trade mark is a well-known trade mark, take into account any fact which he considers relevant for determining a trade mark as a well-known trade mark including—

(i) the knowledge or recognition of that trade mark in the relevant section of the public including knowledge in India obtained as a result of promotion of the trade mark;

(ii) the duration, extent and geographical area of any use of that trade mark; (iii) the duration, extent and geographical area of any promotion of the trade mark, including advertising or publicity and presentation, at fairs or exhibition of the goods or services to which the trade mark applies;

(iv) the duration and geographical area of any registration of or any application for registration of that trade mark under this Act to the extent that they reflect the use or recognition of the trade mark;

(v) the record of successful enforcement of the rights in that trade mark, in particular the extent to which the trade mark has been recognised as a well-known trade mark by any court or Registrar under that record.

(7) The Registrar shall, while determining as to whether a trade mark is known or recognised in a relevant section of the public for the purposes of sub-section (6), take into account—

(i) the number of actual or potential consumers of the goods or services;

(ii) the number of persons involved in the channels of distribution of the goods or services;

(iii) the business circles dealing with the goods or services, to which that trade mark applies.

(8) Where a trade mark has been determined to be well known in at least one relevant section of the public in India by any court or Registrar, the Registrar shall consider that trade mark as a well-known trade mark for registration under this Act.

(9) The Registrar shall not require as a condition, for determining whether a trade mark is a well-known trade mark, any of the following, namely:—

(i) that the trade mark has been used in India;

(ii) that the trade mark has been registered;

(iii) that the application for registration of the trade mark has been filed in India;

(iv) that the trade mark—

(a) is well-known in; or

(b) has been registered in; or

(c) in respect of which an application for registration has been filed in, any jurisdiction other than India, or

(v) that the trade mark is well-known to the public at large in

(10) While considering an application for registration of a trade mark and opposition filed in respect thereof, the Registrar shall—

(i) protect a well-known trade mark against the identical or similar trade marks;

(ii) take into consideration the bad faith involved either of the applicant or the opponent affecting the right relating to the trade mark.

(11) Where a trade mark has been registered in good faith disclosing the material informations to the Registrar or where right to a trade mark has been acquired through use in good faith before the commencement of this Act, then, nothing in this Act shall prejudice the validity of the registration of that trade mark or right to use that trade mark on the ground that such trade mark is identical with or similar to a well-known trade mark.

15. Registration of parts of trademarks and of trade marks as a series.-

(1) Where the proprietor of a trade mark claims to be entitled to the exclusive use of any part thereof separately, he may apply to register the whole and the part as separate trade marks.

(2) Each such separate trade mark shall satisfy all the conditions applying to and have all the incidents of, an independent trade mark.

(3) Where a person claiming to be the proprietor of several trade marks in respect of the same or similar goods or services or description of goods or description of services, which, while resembling each other in the material particulars thereof, yet differ in respect of—

(a) statement of the goods or services in relation to which they are respectively used or proposed to be used; or

(b) statement of number, price, quality or names of places; or

(c) other matter of a non-distinctive character which does not substantially affect the identity of the trade mark; or

(d) colour,

seeks to register those trade marks, they may be registered as a series in one registration.

17. Effect of registration of parts of a mark.— (1) When a trade mark consists of several matters, its registration shall confer on the proprietor exclusive right to the use of the trade mark taken as a whole.

(2) Notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (1), when a trade mark—

(a) contains any part—

(i) which is not the subject of a separate application by the proprietor for registration as a trade mark; or

(ii) which is not separately registered by the proprietor as a trade mark; or

(b) contains any matter which is common to the trade or is otherwise of a non- distinctive character,

the registration thereof shall not confer any exclusive right in the matter forming only a part of the whole of the trade mark so registered.

27. No action for infringement of an unregistered trade mark.— (1) No person shall be entitled to institute any proceeding to prevent, or to recover damages for, the infringement of an unregistered trade mark.

(2) Nothing in this Act shall be deemed to affect rights of action against any person for passing off goods or services as the goods of another person or as services provided by another person, or the remedies in respect thereof.”

28. Rights conferred by registration.—(1) Subject to the other provisions of this Act, the registration of a trade mark shall, if valid, give to the registered proprietor of the trade mark the exclusive right to the use of the trade mark in relation to the goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered and to obtain relief in respect of infringement of the trade mark in the manner provided by this Act.

(2) The exclusive right to the use of a trade mark given under sub-section (1) shall be subject to any conditions and limitations to which the registration is subject.

(3) Where two or more persons are registered proprietors of trade marks, which are identical with or nearly resemble each other, the exclusive right to the use of any of those trade marks shall not (except so far as their respective rights are subject to any conditions or limitations entered on the register) be deemed to have been acquired by any one of those persons as against any other of those persons merely by registration of the trade marks but each of those persons has otherwise the same rights as against other persons (not being registered users using by way of permitted use) as he would have if he were the sole registered proprietor.

29. Infringement of registered trade marks.—(1) A registered trade mark is infringed by a person who, not being a registered proprietor or a person using by way of permitted use, uses in the course of trade, a mark which is identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered and in such manner as to render the use of the mark likely to be taken as being used as a trade mark.

(2) A registered trade mark is infringed by a person who, not being a registered proprietor or a person using by way of permitted use, uses in the course of trade, a mark which because of—

(a) its identity with the registered trade mark and the similarity of the goods or services covered by such registered trade mark; or

(b) its similarity to the registered trade mark and the identity or similarity of the goods or services covered by such registered trade mark; or

(c) its identity with the registered trade mark and the identity of the goods or services covered by such registered trade mark,

is likely to cause confusion on the part of the public, or which is likely to have an association with the registered trade mark.

(3) In any case falling under clause (c) of sub-section (2), the court shall presume that it is likely to cause confusion on the part of the public.

(4) A registered trade mark is infringed by a person who, not being a registered proprietor or a person using by way of permitted use, uses in the course of trade, a mark which—

(a) is identical with or similar to the registered trade mark; and

(b) is used in relation to goods or services which are not similar to those for which the trade mark is registered; and

(c) the registered trade mark has a reputation in India and the use of the mark without due cause takes unfair advantage of or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or repute of the registered trade mark.

(5) A registered trade mark is infringed by a person if he uses such registered trade mark, as his trade name or part of his trade name, or name of his business concern or part of the name, of his business concern dealing in goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

(6) For the purposes of this section, a person uses a registered mark, if, in particular, he—

(a) affixes it to goods or the packaging thereof;

(b) offers or exposes goods for sale, puts them on the market, or stocks them for those purposes under the registered trade mark, or offers or supplies services under the registered trade mark;

(c)imports or exports goods under the mark; or

(d) uses the registered trade mark on business papers or in

(7) A registered trade mark is infringed by a person who applies such registered trade mark to a material intended to be used for labeling or packaging goods, as a business paper, or for advertising goods or services, provided such person, when he applied the mark, knew or had reason to believe that the application of the mark was not duly authorized by the proprietor or a licensee.

(8) A registered trade mark is infringed by any advertising of that trade mark if such advertising—

(a) takes unfair advantage of and is contrary to honest practices in industrial or commercial matters; or

(b) is detrimental to its distinctive character; or

(c) is against the reputation of the trade

(9) Where the distinctive elements of a registered trade mark consist of or include words, the trade mark may be infringed by the spoken use of those words as well as by their visual representation and reference in this section to the use of a mark shall be construed accordingly.

135. Relief in suits for infringement or for passing off.—(1) The relief which a court may grant in any suit for infringement or for passing off referred to in section 134 includes injunction (subject to such terms, if any, as the court thinks fit) and at the option of the plaintiff, either damages or an account of profits, together with or without any order for the delivery-up of the infringing labels and marks for destruction or erasure.

(2) The order of injunction under sub-section (1) may include an ex parte injunction or any interlocutory order for any of the following matters, namely:—

(a) for discovery of documents; (b) preserving of infringing goods, documents or other evidence which are related to the subject-matter of the suit;

(c) restraining the defendant from disposing of or dealing with his assets in a manner which may adversely affect plaintiff’s ability to recover damages, costs or other pecuniary remedies which may be finally awarded to the plaintiff.

(3) Notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (1), the court shall not grant relief by way of damages (other than nominal damages) or on account of profits in any case—

(a) where in a suit for infringement of a trade mark, the infringement complained of is in relation to a certification trade mark or collective mark; or (b) where in a suit for infringement the defendant satisfies the court—

(i) that at the time he commenced to use the trade mark complained of in the suit, he was unaware and had no reasonable ground for believing that the trade mark of the plaintiff was on the register or that the plaintiff was a registered user using by way of permitted use; and

(ii) that when he became aware of the existence and nature of the plaintiff’s right in the trade mark, he forthwith ceased to use the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which it was registered; or

(c) where in a suit for passing off, the defendant satisfies the court—

(i) that at the time he commenced to use the trade mark complained of in the suit, he was unaware and had no reasonable ground for believing that the trade mark for the plaintiff was in use; and

(ii) that when he became aware of the existence and nature of the plaintiff’s trade mark he forthwith ceased to use the trade mark complained of.”

18.1. A plain reading of the above provisions indicates that Section 2(h) defines “deceptively similar” as a mark that so nearly resembles another mark as to be likely to cause confusion or deception. This definition forms the cornerstone of the test applied in registration refusals and infringement disputes. Section 2(m), (q), (v), (w), (zb) respectively define mark, package, registered proprietor, registered trademark, and trademark, laying the foundational terms used throughout the Act.

18.2 Section 9(1) bars registration of trademarks that are deceptive, non- distinctive, or commonly used in trade. However, the proviso carves out an exception where such marks have acquired distinctiveness through prolonged and exclusive use – commonly referred to as having acquired a “secondary meaning”.

18.3 Section 11 prohibits registration of marks identical or similar to earlier marks for identical or similar goods or services, where a likelihood of confusion exists. It further extends protection to well-known trademarks, even across dissimilar goods or services, thereby recognizing the doctrine of dilution.

18.4 Section 15 permits registration of series marks, provided that the differences between them do not materially affect their Section 17 clarifies that exclusive rights are granted over the mark as a whole (sub-section (1)), while sub-section (2) ensures that generic or non-distinctive elements within a composite mark are not monopolized individually.

18.5 Section 27(2) recognizes the common law remedy of passing off, thereby ensuring that rights in an unregistered trademark can still be protected based on prior use.

18.6 Section 28 confers on the registered proprietor exclusive rights to use the trademark and to obtain relief in case of Section 29 outlines specific instances of infringement:

Sub-section (1) covers identical or deceptively similar marks used for identical goods or services,

Sub-section (2) expands the scope to include similar goods / services likely to cause confusion,

Sub-section (4) protects well-known marks even in cases of dissimilar goods / services provided there is unfair advantage or damage to the mark’s reputation, Significantly, Section 29(3) raises a presumption of confusion when identical marks are used for identical goods/ services, easing the evidentiary burden on the plaintiff.

18.7 Finally, Section 135 empowers courts to grant relief in suits for infringement or passing off. This includes temporary or permanent injunctions, damages, account of profits, and orders for seizure of infringing goods. Importantly, courts are authorized to grant ex parte and interlocutory relief to prevent continued misuse or dilution of trademarks during the pendency of litigation.

18.8 In essence, the Trade Marks Act, 1999 provides a comprehensive statutory framework for protecting registered trademarks, while also preserving the rights of prior users through passing off The Act clearly distinguishes between absolute and relative grounds for refusal of registration and provides effective enforcement mechanisms. Crucially, the guiding test is the likelihood of confusion in the mind of an average consumer – not actual confusion – which serves as the touchstone for both refusal of registration and infringement proceedings. In the present case, the issues of similarity, reputation, and consumer confusion must be analyzed within this statutory scheme.

VI. JUDICIAL PRONOUNCEMENTS

19. Before proceeding further to analyse the facts of the case, we deem it necessary to refer and consider the judicial precedents on trademark infringement and passing off, to assess whether, in the present case, the appellants are entitled to the relief of interim injunction.

19.1 In the Privy Council decision of Coca-Cola Company of Canada v. Pepsi-Cola Company of Canada Ltd.16) the issue pertained to alleged infringement under the Unfair Competition Act, 1932. Both parties were using their respective marks – Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola – for similar non-alcoholic beverages in the same market. The Privy Council upheld the lower court’s finding that no infringement had occurred. It observed that although both marks contained the common term “cola”, the word was descriptive in nature and not capable of exclusive appropriation. The essential and distinctive features of the competing marks were identified as “Coca” and “Pepsi”, which were held sufficient to distinguish the respective goods. The ruling underscored that trademark protection does not extend to ordinary, descriptive, or laudatory terms unless they have acquired a secondary meaning or distinctiveness. Consequently, the mere presence of the shared term “Cola” was held inadequate to establish deceptive similarity or likelihood of confusion. The relevant paragraphs of the decision are extracted below for ready reference:

“4. The contemporaneous use of both marks in the same area in association with wares of the same kind is not in dispute. The actual question for decision in the present case may, therefore, in the light of the above definition be stated thus — Does the mark used by the defendant so resemble the plaintiff’s registered mark or so clearly suggest the idea conveyed by it, that its use is likely to cause dealers in or users of non-alcoholic beverages to infer that the plaintiff assumed responsibility for the character or quality or place of origin of Pepsi-Cola? The President of the Exchequer Court answered the question in the affirmative; the Supreme Court answered it in the negative. Their Lordships are in agreement with the Supreme Court.

5. The case appears to them to be one which is free from complications, and which raises neither new matter of principle nor novel question of trademark law. The only peculiar feature of the case is the dearth of evidence, attributable doubtless to the procedure adopted by the plaintiff at the trial. The only matters proved before the plaintiff’s case was closed were (1) the plaintiff’s registered mark and

(2) the user by the defendant of the mark alleged to be an infringement. No evidence of (to put it shortly) confusion either actual or probable was adduced. It was contended that a statement by a witness called by the defendant (one Charles Guth) was proof of actual confusion. Guth was general manager of a United States company which owns the capital stock of the defendant. He was also President of a New York company called Loft Incorporated which owned a large number of candy stores in New York at which Coca-Cola was sold. Subsequently the sale of Coca-Cola was discontinued, and Pepsi-Cola was sold at the stores. A passing off action was brought by the Delaware Coca-Cola Company against Loft Incorporated. The judge of the Court of Chancery, Delaware, dismissed the action holding that Loft Incorporated was not responsible for the acts of its agents of which evidence had been given. In the course of his cross-examination in the Exchequer Court Guth was asked “Then you have no quarrel with the Chancellor’s decision as to the facts expressed in his opinion?” and he answered “None at all.” It was argued that this answer proved the fact found in the judgment of the Chancellor viz. (as quoted by the President of the Exchequer Court from a report of the case) that “the uncontradicted evidence shows that substitutions were made by employees of the defendants of a product other than Coca-Cola for that beverage when calls for the same were made.”

6. The learned President relied on this judgment “as very formidable support to the plaintiff’s contention that … there is likelihood of confusion”; but in their Lordships’ opinion he was not entitled to refer to or rely upon a judgment given in proceedings to which neither the plaintiff nor the defendant was a party, as proving the facts stated therein. Those facts are in no way proved thereby, nor are they in any way proved by the answer of Guth which has been quoted above. Guth could not of his own knowledge either quarrel or agree with the Chancellor’s decision as to what it was that had happened in the numerous stores, and was described by the word “substitutions”. There was accordingly no evidence before the Exchequer Court of confusion actual or probable. In these circumstances, the question for determination must be answered by the Court, unaided by outside evidence, after a comparison of the defendant’s mark as used with the plaintiff’s registered mark, not placing them side by side, but by asking itself whether, having due regard to relevant surrounding circumstances, the defendant’s mark as used is similar (as defined by the Act) to the plaintiff’s registered mark as it would be remembered by persons possessed of an average memory with its usual imperfections.

7. In the present case two circumstances exist which are of importance in this connexion. The first is the information which is afforded by dictionaries in relation to the word “Cola”. While questions may sometimes arise as to the extent to which a Court may inform itself by reference to dictionaries there can, their Lordships think, be no doubt that dictionaries may properly be referred to in order to ascertain not only the meaning of a word, but also the use to which the thing (if it be a thing) denoted by the word is commonly put. A reference to dictionaries shows that Cola or Kola is a tree whose seed or nut is “largely used for chewing as a condiment and digestive” (Murray), a nut of which “the extract is used as a tonic drink” (Webster), and which is “imported into the United States for use in medical preparations and summer drinks” (Encyclopaedia Americana). Cola would therefore appear to be a word which might appropriately be used in association with beverages and in particular with that class of non-alcoholic beverages colloquially known by the description of “soft drinks”. That in fact the word “Cola” or “Kola” has been so used in Canada is established by the second of the two circumstances before referred to. The defendant put in evidence a series of 22 trade marks registered in Canada from time to time during a period of 29 years, viz., from 1902 to 1930, in connexion with beverages. They include the mark of the plaintiff and the registered mark of the defendant. The other 20 marks consist of two or more words or a compound word, but always containing the word “Cola” or “Kola”. The following are a few samples of the bulk; — “Kola Tonic Wine” “La-Kola” “Cola-Claret”, “Rose-Cola”, “Orange Kola” “O’Keefe’s Cola”, “Royal Cola”. Their Lordships agree with the Supreme Court in attributing weight to those registrations as showing that the word Cola (appropriate for the purpose as appears above) had been adopted in Canada as an item in the naming of different beverages. The proper comparison must be made with that fact in mind.

8. Numerous cases were cited in the Courts of Canada and before the Board in which the question of infringement of various marks has been considered and decided; but except when some general principle is laid down, little assistance is derived from authorities in which the question of infringement is discussed in relation to other marks and other circumstances. The plaintiff claimed that by virtue of S. 23(5)(b), Unfair Competition Act, 1932 its registered mark was both a word mark and a design mark; and their Lordships treat it accordingly. If it be viewed simply as a word mark consisting of g “Coca” and “Cola” joined by a hyphen, and the fact be borne in mind that Cola is a word in common use in Canada in naming beverages, it is plain that the distinctive feature in this hyphenated word, is the first word “Coca” and not “Cola”. “Coca” rather than “Cola” is what would remain in the average memory. It is difficult indeed impossible, to imagine that the mark Pepsi-Cola as used by the defendant, in which the distinctive feature is, for the same reason the first word “Pepsi” and not “Cola”, would lead anyone to confuse it with the registered mark of the plaintiff. If it be viewed as a design mark the same result follows. The only resemblance lies in the fact that both contain the word “Cola”, and neither is written in block letters, but in script with flourishes. But the letters and flourishes in fact differ very considerably notwithstanding the tendency of words written in script with flourishes to bear a general resemblance to each other. There is no need to specify the differences in detail; it is sufficient to say that in their Lordships’ opinion, the mark used by the defendant, viewed as a pattern or picture, would not lead a person with an average recollection of the plaintiff’s registered mark to confuse it with the pattern or picture represented by that mark. In the result their Lordships are of opinion that the trade mark used by the defendant and the registered mark of the plaintiff are not trade marks so nearly resembling each other or so clearly suggesting the idea conveyed by each other that the contemporaneous use of both in the same area in association with wares of the same kind would be likely to cause dealers in or users of such wares to infer that the same person assumed responsibility for their character or quality or for the conditions under which or the class of persons by whom they were produced or for their place of origin. The defendant therefore has not adopted for use in Canada in connexion with its wares a trade mark which in any way offends against the provisions of S. 3, Unfair Competition Act, 1932. Their Lordships will humbly advise His Majesty that this appeal and the cross appeal should be dismissed. The plaintiff will pay the costs of the appeal and the defendant will pay the costs of the cross appeal with the usual set-off.

Appeal dismissed.”

19.2 In Corn Products Refining Co., v. Shangrila Food Products Ltd. 7, the appellant, who was the registered proprietor of the trademark Glucovita used in relation to glucose-based food products, sought an injunction against the respondent who had commenced marketing a similar product under the mark Gluvita. The primary contention was one of deceptive similarity and passing This court held that the two marks – Glucovita and Gluvita – were phonetically and visually similar, and likely to mislead or confuse an average consumer of imperfect recollection. The court, accordingly, granted an injunction restraining the respondent from using the impugned mark. The following paragraph is apposite in this regard:

“15. Now it is a well recognised principle, that has to be taken into account in considering the possibility of confusion arising between any two trademarks, that, where those two marks contain a common element which is also contained in a number of other marks in use in the same market such a common occurrence in the market tends to cause purchasers to pay more attention to the other features of the respective marks and to distinguish between them by those features. This principle clearly requires that the marks comprising the common element shall be in fairly extensive use and, as I have mentioned, in use in the market in which the marks under consideration are being or will be used.”

19.3 In Amritdhara Pharmacy v. Satya Deo Gupta (supra), this Court had extensively analysed the principles governing distinctiveness and likelihood of confusion in trademarks. It held that the marks ‘Amritdhara’ and ‘Lakshmandhara’ were deceptively similar, owing to their structural and phonetic resemblance. Reaffirming the anti-dissection rule, the court observed that an average consumer does not dissect a trademark into its components or analyze its etymology, but perceives the mark as a whole. Further, the Court noted that both marks were used for similar medicinal products targeted at a wide consumer base, including illiterate and semi-literate From the standpoint of an average purchaser with imperfect recollection, the overall similarity in sound and structure was likely to cause confusion or deception. Mere etymological or lexical differences were considered immaterial. While several precedents on deceptively similar composite marks were cited, the Court emphasized that each case must be determined on its own facts. The degree of resemblance sufficient to create confusion cannot be predetermined and must be assessed in light of the overall context. The admissibility of earlier decisions cited was also debated; however, the Court found it unnecessary to rule on their admissibility, as those decisions were not determinative in resolving the issue of deceptive similarity between Amritdhara and Lakshmandhara. The following paragraph from the judgment is apposite:

“6. It will be noticed that the words used in the sections relevant for our purpose are “likely to deceive or cause confusion.” The Act does not lay down any criteria for determining what is likely to deceive or cause confusion. Therefore, every case must depend on its own particular facts, and the value of authorities lies not so much in the actual decision as in the tests applied for determining what is likely to deceive or cause confusion. On an application to register, the Registrar or an opponent may object that the trade mark is not registerable by reason of cl. (a) of s.8, or sub-s. (1) of s.10, as in this case. In such a case the onus is on the applicant to satisfy the Registrar that the trade mark applied for is not likely to deceive or cause confusion. In cases in which the tribunal considers that there is doubt as to whether deception is likely, the application should be refused. A trade mark is likely to deceive or cause confusion by the resemblance to another already on the Register if it is likely to do so in the course of its legitimate use in a market where the two marks are assumed to be in use by traders in that market….

For deceptive resemblance two important questions are: (1) who are the persons whom the resemblance must be likely to deceive or confuse, and (2) what rules of comparison are to be. adopted in judging whether such resemblance exists. As to confusion, it is perhaps an appropriate description of the state of mind of a customer who, on seeing a mark thinks, that it differs from the mark on goods which’ he has previously bought, but is doubtful whether that impression is Dot due to imperfect recollection. (See Kerly on Trade Marks, 8th edition, p. 400.) ”

7. … We must consider, the overall similarity of the two composite words ‘Amritdhara’ and ‘Lakshmandhara’. We do not think that the learned Judges of the High Court were right in Paying that no Indian would mistake one ‘for the other. An unwary purchaser of average intelligence and imperfect recollection would not, as the High Court supposed, split the name into its component parts and consider the etymological meaning thereof or even consider the meanings of the composite words as ‘current of nectar’ or current of Lakshman’. He would go more by the overall structural and phonetic similarity and the nature of the medicine he has previously purchased, or has been told about, or about which has other vise learnt and which he wants to purchase. Where the trade relates to goods largely sold to illiterate or badly educated persons, it is no answer to say that a person educated in the Hindi language would go by the etymological or ideological meaning and, see the difference between ‘current of nectar’ and current of Lakshman’. ‘Current of Lakshman in a literal sense has no meaning to give it meaning one must further make the inference that the ‘current or stream’ is as pure and strong as Lakshman of the Ramayana. An ordinary Indian villager or townsmen will perhaps know Lakshman, the story of the Ramayana being familiar to him but we doubt if he would etymologine to the extent of seeing the socalled ideological difference between ‘Amritdhara’ and ‘Lakshmandhara’. He would go more by the similarity of the two names in the context of the widely known medicinal preparation which he wants for his ailments. We agree that the use of the word ‘dhara’ which literally means ‘Current or stream’ is not by itself decisive of the matter. What we have to consider here is the overall similarity of the composite words, having regard to the circumstance that the goods bearing the two names are medicinal preparations of the same description. We are aware that the admission of a mar is not to be refused, because unusually stupid people, “fools or idiots”, may be deceived. A critical comparison of the two names may disclose some points of difference, but an unwary purchaser of average intelligence and imperfect recollection would be deceived by the overall similarity of the two names having regard to the nature of the medicine he is looking for with a somewhat vague recollection that he had purchased a similar medicine on a previous occasion with. a similar name…..

9. Nor do we think that the High Court was. right in thinking that the appellant was claiming a. monopoly in the common Hindi word ‘dhara’. We do not think that is quite the position here. What the appellant is claiming is its right under s.21 of the Act, the exclusive right to the use of its trade mark, and to oppose the registration of a trade mark which go nearly resembles its trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion….

12. On a consideration of all the circumstances, we have come to the conclusion that the overall similarity between the two names in respect of the same description of goods was likely to cause deception or confusion within the meaning of s. 10(1) of the Act and Registrar was right in the view he expressed. The High Court was in error taking a contrary view.”

19.4. In Kaviraj Pandit Durga Dutt Sharma v. Navaratna Pharmaceutical Laboratories (supra), the appellant who was the registered proprietor of the trademark ‘Navaratna Pharmacy’, instituted a suit for infringement and passing off against the respondent, who was manufacturing ayurvedic medicines under a similar name. The appellant alleged that the respondent’s use of the name was likely to cause confusion among consumers. This court held that the claim of infringement was not made out, as the two marks were not sufficiently similar to deceive or confuse the public within the meaning of the Trade Marks Act. However, the Court upheld the passing off claim, observing that the overall similarity in name and trade dress could mislead consumers and adversely affect the goodwill of the appellant’s business. The following paragraphs are relevant in this context:

“28. … The finding in favour of the appellant to which the learned counsel drew our attention was based upon dissimilarity of the packing in which the goods of the two parties were vended, the difference in the physical appearance of the two packets by reason of the variation in the colour and other features and their general get-up together with the circumstance that the name and address of the manufactory of the appellant was prominently displayed on his packets and these features were all set out for negativing the respondent’s claim that the appellant had passed off his goods as those of the respondent. These matters which are of the essence of the cause of action for relief on the ground of passing off play but a limited role in an action for infringement of a registered trade mark by the registered proprietor who has a statutory right to that mark and who has a statutory remedy for the event of the use by another of that mark or a colourable imitation thereof. While an action for passing off is a Common Law remedy being in substance an action for deceit, that is, a passing off by a person of his own goods as those of another, that is not the gist of an action for infringement. The action for infringement is a statutory remedy conferred on the registered proprietor of a registered trade mark for the vindication of the exclusive right to the use of the trade mark in relation to those goods (Vide Section 21 of the Act). The use by the defendant of the trade mark of the plaintiff is not essential in an action for passing off, but is the sine qua non in the case of an action for infringement. No doubt, where the evidence in respect of passing off consists merely of the colourable use of a registered trade mark, the essential features of both the actions might coincide in the sense that what would be a colourable imitation of a trade mark in a passing off action would also be such in an action for infringement of the same trade mark. But there the correspondence between the two ceases. In an action for infringement, the plaintiff must, no doubt, make out that the use of the defendant’s mark is likely to deceive, but where the similarity between the plaintiff’s and the defendant’s mark is so close either visually, phonetically or otherwise and the court reaches the conclusion that there is an imitation, no further evidence is required to establish that the plaintiff’s rights are violated. Expressed in another way, if the essential features of the trade mark of the plaintiff have been adopted by the defendant, the fact that the get-up, packing and other writing or marks on the goods or on the packets in which he offers his goods for sale show marked differences, or indicate clearly a trade origin different from that of the registered proprietor of the mark would be immaterial; whereas in the case of passing off, the defendant may escape liability if he can show that the added matter is sufficient to distinguish his goods from those of the plaintiff.

29. When once the use by the defendant of the mark which is claimed to infringe the plaintiff’s mark is shown to be “in the course of trade”, the question whether there has been an infringement is to be decided by comparison of the two marks. Where the two marks are identical no further questions arise; for then the infringement is made out. When the two marks are not identical, the plaintiff would have to establish that the mark used by the defendant so nearly resembles the plaintiff’s registered trade mark as is likely to deceive or cause confusion and in relation to goods in respect of which it is registered (Vide Section 21). A point has sometimes been raised as to whether the words “or cause confusion” introduce any element which is not already covered by the words “likely to deceive” and it has sometimes been answered by saying that it is merely an extension of the earlier test and does not add very materially to the concept indicated by the earlier words “likely to deceive”. But this apart, as the question arises in an action for infringement the onus would be on the plaintiff to establish that the trade mark used by the defendant in the course of trade in the goods in respect of which his mark is registered, is deceptively This has necessarily to be ascertained by a comparison of the two marks — the degree of resemblance which is necessary to exist to cause deception not being capable of definition by laying down objective standards. The persons who would be deceived are, of course, the purchasers of the goods and it is the likelihood of their being deceived that is the subject of consideration. The resemblance may be phonetic, visual or in the basic idea represented by the plaintiff’s mark. The purpose of the comparison is for determining whether the essential features of the plaintiff’s trade mark are to be found in that used by the defendant. The identification of the essential features of the mark is in essence a question of fact and depends on the judgment of the Court based on the evidence led before it as regards the usage of the trade. It should, however, be borne in mind that the object of the enquiry in ultimate analysis is whether the mark used by the defendant as a whole is deceptively similar to that of the registered mark of the plaintiff.”

19.5. In Parle Products (P) Ltd., v. J.P. & Co., Mysore17, this Court laid down the test for deceptive similarity in trademark The dispute concerned the plaintiff’s registered trademark and distinctive packaging for “Glucose Biscuits”, and the defendant’s use of similar packaging and get-up for their biscuits marketed under the name “Glucobiscuit”. The Court observed that the two marks, taken with their overall packaging and presentation, were deceptively similar – particularly given the class of consumers targeted, namely children and the general public, who are not expected to conduct a detailed comparison. It was held that an average consumer, possessing imperfect recollection, could easily be misled due to the visual, phonetic, and structural similarities in the competing products. Accordingly, the Court ruled in favour of the plaintiff, and restrained the defendant from continuing use of the impugned mark. The relevant paragraph is extracted below for better appreciation:

“9. It is therefore clear that in order to come to the conclusion whether one mark is deceptively similar to another, the broad and essential features of the two are to be considered. They should not be placed side by side to find out if there are any differences in the design and if so, whether they are of such character as to prevent one design from being mistaken for the other. It would be enough if the impugned mark bears such an overall similarity to the registered mark as would be likely to mislead a person usually dealing with one to accept the other if offered to him. In this case we find that the packets are practically of the same size, the color scheme of the two wrappers is almost the same; the design on both though not identical bears such a close resemblance that one can easily be mistaken for the other. The essential features of both are that there is a girl with one arm raised and carrying something in the other with a cow or cows near her and hens or chickens in the foreground. In the background there is a farm house with a fence. The word “Gluco Biscuits” in one and “Glucose Biscuits” on the other occupy a prominent place at the top with a good deal of similarity between the two writings. Anyone in our opinion who has a look at one of the packets today may easily mistake the other if shown on another day as being the same article which he had seen before. If one was not careful enough to note the peculiar features of the wrapper on the plaintiffs goods, he might easily mistake the defendants’ wrapper for the plaintiffs if shown to him some time after he had seen the plaintiffs’. After all, an ordinary purchaser is not gifted with the powers of observation of a Sherlock Holmes. We have therefore no doubt that the defendants’ wrapper is deceptively similar to the plaintiffs’ which was registered. We do not think it necessary to refer to the decisions referred to at the Bar as in our view each case will have to be, judged on its own features and it would be of no use to note on how many points there was similarity and in how many others there was absence of it.”

19.6. In Cadila Health Care v. Cadila Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (supra), it was held that even minor differences may be insufficient if the overall impression conveyed by the marks is likely to deceive or cause confusion. The applicable test is not one of exact or absolute similarity, but whether the essential and distinctive features of the plaintiff’s mark have been appropriated by the defendant in a manner likely to mislead or confuse the average consumer. The following paragraph is apposite in this regard:

“16. Dealing once again with medicinal products, this Court in F. Hoffmann-La Roche & Co. Ltd. v. Geoffrey Manner & Co. (P) Ltd. [(1969) 2 SCC 716] had to consider whether the word “Protovit” belonging to the appellant was similar to the word “Dropovit” of the respondent. This Court, while deciding the test to be applied, observed at pp. 720-21 as follows: (SCC para 7)

“The test for comparison of the two word marks were formulated by Lord Parker in Pianotist Co. Ltd.’s application [(1906) 23 RPC 774] as follows:

‘You must take the two words. You must judge of them, both by their look and by their sound. You must consider the goods to which they are to be applied. You must consider the nature and kind of customer who would be likely to buy those goods. In fact, you must consider all the surrounding circumstances; and you must further consider what is likely to happen if each of those trade marks is used in a normal way as a trade mark for the goods of the respective owners of the marks. If, considering all those circumstances, you come to the conclusion that there will be a confusion, that is to say, not necessarily that one man will be injured and the other will gain illicit benefit, but that there will be a confusion in the mind of the public which will lead to confusion in the goods — then you may refuse the registration, or rather you must refuse the registration in that case.’

It is necessary to apply both the visual and phonetic tests. In Aristoc Ltd. v. Rysta Ltd. [62 RPC 65] the House of Lords was considering the resemblance between the two words ‘Aristoc’ and ‘Rysta’. The view taken was that considering the way the words were pronounced in English, the one was likely to be mistaken for the other. Viscount Maugham cited the following passage of Lord Justice Lukmoore in the Court of Appeal, which passage, he said, he completely accepted as the correct exposition of the law:

‘The answer to the question whether the sound of one word resembles too nearly the sound of another so as to bring the former within the limits of Section 12 of the Trade Marks Act, 1938, must nearly always depend on first impression, for obviously a person who is familiar with both words will neither be deceived nor confused. It is the person who only knows the one word and has perhaps an imperfect recollection of it who is likely to be deceived or confused. Little assistance, therefore, is to be obtained from a meticulous comparison of the two words, letter by letter and syllable by syllable, pronounced with the clarity to be expected from a teacher of elocution. The Court must be careful to make allowance for imperfect recollection and the effect of careless pronunciation and speech on the part not only of the person seeking to buy under the trade description, but also of the shop assistant ministering to that person’s wants.’

It is also important that the marks must be compared as wholes. It is not right to take a portion of the word and say that because that portion of the word differs from the corresponding portion of the word in the other case there is no sufficient similarity to cause confusion. The true test is whether the totality of the proposed trade mark is such that it is likely to cause deception or confusion or mistake in the minds of persons accustomed to the existing trade mark. Thus in Lavroma case Lord Johnston said:

‘… we are not bound to scan the words as we would in a question of comparatio literarum. It is not a matter for microscopic inspection, but to be taken from the general and even casual point of view of a customer walking into a shop.’ ”

On the facts of that case this Court came to the conclusion that taking into account all circumstances the words “Protovit” and “Dropovit” were so dissimilar that there was no reasonable probability of confusion between the words either from visual or phonetic point of view.”

19.6.1. Further, in the same decision, this Court laid down the parameters to be applied in a passing off action involving deceptive similarity of marks. The relevant paragraph is usefully extracted below:

“35. Broadly stated, in an action for passing-off on the basis of unregistered trade mark generally for deciding the question of deceptive similarity the following factors are to be considered:

(a) The nature of the marks e. whether the marks are word marks or label marks or composite marks i.e. both words and label works.

(b) The degree of resemblance between the marks, phonetically similar and hence similar in idea.

(c) The nature of the goods in respect of which they are used as trade

(d) The similarity in the nature, character and performance of the goods of the rival traders.

(e) The class of purchasers who are likely to buy the goods bearing the marks they require, on their education and intelligence and a degree of care they are likely to exercise in purchasing and/or using the goods.

(f) The mode of purchasing the goods or placing orders for the

(g) Any other surrounding circumstances which may be relevant in the extent of dissimilarity between the competing marks.

36. Weightage to be given to each of the aforesaid factors depending upon facts of each case and the same weightage cannot be given to each factor in every case.”

19.7.In Khoday Distilleries Limited (Now known as Khoday India Limited) Scotch Whisky Association and others (supra), this Court addressed the question of whether the use of the expression “Peter Scot” by an Indian manufacturer for whisky amounted to passing off or infringement of the respondents’ rights associated with the term “Scotch”. The respondents contended that the mark “Peter scot” was deceptively similar to “scotch” and was likely to mislead consumers into believing that the product had some connection with genuine Scotch whisky originating from Scotland. The appellant however contended that. the mark “Peter Scot” was derived from the founder’s son’s name and was adopted without any intent to deceive. This Court rejected the plea of deceptive similarity, holding that the term “Scot” in Peter Scot was not sufficient, in and of itself, to mislead or deceive the public into believing that the product originated in Scotland. It was emphasized that the test of deceptive dissimilarly must be applied from the standpoint of an average consumer with imperfect recollection. Mere phonetic similarity the Court held, is not determinative unless it leads to actual or likely confusion. Furthermore, in actions for passing off, an intention to deceive must be established, and mere similarity in names without such intent is insufficient. Although “Scotch” constitutes a protected geographical indication, the Court found that “Peter Scot” was a bona fide and honest adoption, not intended to exploit the reputation of Scotch whisky. Ultimately, it was held that no actionable confusion or deception had been proved, and accordingly, the injunction sought by the respondents was rightly declined. The decision reaffirms that the test of deceptive similarity must be applied holistically, having regard to the overall impression created by the mark, rather than focusing merely on phonetic or structural resemblance in isolation. The following paragraphs are pertinent in this regard:

“75. The tests which are, therefore, required to be applied in each case would be different. Each word must be taken separately. They should be judged by their look and by their sound and must consider the goods to which they are to be applied. Nature and the kind of customers who would likely to buy goods must also be considered. Surrounding circumstances play an important factor. What would be likely to happen if each of those trademarks is used in a normal way as a trade mark of the goods of the respective owners of the marks would also be a relevant factor.

76. Thus, when and how a person would likely be confused is a very relevant