Menstrual Health as a Facet of Right to Life

Dr. Jaya Thakur v Government of India

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that menstrual health is an aspect of right to life and the right to free and compulsory education under Article 21 and 21A respectively.

Dr. Jaya Thakur filed a writ petition under Article 32 requesting the Court to direct all states and union territories to provide free...

Case Details

Judgement Date: 30 January 2026

Citations: 2026 INSC 97 | 2026 SCO.LR (2)[1][4]

Bench: J.B. Pardiwala J, R. Mahadevan J

Keyphrases: Article 32—Menstruation as barrier to education—Drop-out and absenteeism—Lack of affirmative action—Menstrual hygiene and health—Substantive equality—Menstrual hygiene as right under Article 21 and 21A—Prayer granted.

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

J.B. PARDIWALA & R. MAHADEVAN, JJ.:

“A period should end a sentence – not a girl’s education.”

1. We are tempted to preface our judgment with the words of Melissa Berton, an American educator, social activist, and producer. The statement articulated above resonate with an undiminishing force in the present petition as well. The issues that have unfolded before us echo the very same judicial disquiet. Even with the passage of time, the challenges that beset a girl child’s education persist in much the same form.

I. THE CONTEXT

2. The petitioner, who is a social worker, has filed the present petition under Article 32 of the Constitution in public interest seeking appropriate directions to the respondents – the Union of India, the States and Union Territories respectively to ensure providing of (i) free sanitary pads to every female child studying between classes 6 & 12; and (ii) a separate toilet for females in all government aided and residential schools. Apart from this, certain other consequential reliefs have also been sought for in public interest including the maintenance of toilets and the spread of awareness programmes. The prayer in the petition reads thus:-

“a. issue a writ order or directions in the nature of Mandamus to the Respondents to provide the free sanitary pads to girl child who are studying from 6th to 12th class and;

b. issue a writ order or directions in the nature of Mandamus to the Respondents to provide the separate girl toilet in all Government, Aided and residential schools;

c. issue a writ order or directions in the nature of Mandamus to the Respondents to provide one cleaner in all Government, Aided and residential schools to clean the toilets and;

d. issue a writ order or directions in the nature of Mandamus to the Respondents to provide three-stage awareness programme i.e. Firstly, the spreading of awareness about menstrual health and unboxing the taboos that surround it; Secondly, providing adequate sanitation facilities and subsidized or free sanitary products to women and young students, especially in disadvantaged areas; Thirdly, to ensure an efficient and sanitary manner of menstrual waste disposal and;

e. pass such other or further order/s as this Hon’ble Court may deem it fit in the facts and circumstances of this case.”

II. THE BASICS

3. Menstruation refers to the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue from the inner lining of the uterus through the cervix, which passes out of the body through the vagina at approximately monthly intervals. It occurs when the egg released during ovulation is not fertilized, leading to the breakdown and shedding of the uterine lining. Menarche (the first menstrual period) occurs after the onset of pubertal growth. The average age of a female at the time of menarche is between 8 and 15 years, and it usually occurs at intervals of about 28 days.

4. The Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation in the National Guidelines for Menstrual Hygiene Management defines menstrual hygiene management (hereinafter referred to as “MHM”) as, “(i) articulation, awareness, information and confidence to manage menstruation with safety and dignity using safe hygienic materials together with (ii) adequate water and agents and spaces for washing and bathing with soap and (iii) disposal of used menstrual absorbents with privacy and dignity.” Further, water, sanitation and hygiene (hereinafter referred to as “WASH”) facilities include clean water, sex-separated washrooms, handwashing facilities and MHM.1

5. According to the 2012 Joint Monitoring Programme of the World Health Organization, MHM is defined as thus;

“Women and adolescent girls are using a clean menstrual management material to absorb or collect menstrual blood, that can be changed in privacy as often as necessary, using soap and water for washing the body as required, and having access to safe and convenient facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials. They understand the basic facts linked to the menstrual cycle and how to manage it with dignity and without discomfort or fear.”

6. In the aforesaid context, we may discuss what menstrual poverty or period poverty means. Menstrual poverty, also known as period poverty, refers to the financial burden and obstacles that women face in affording menstrual hygiene, or sanitary products because they are unable to maintain such expenditure. It extends beyond the lack of sanitary products and includes inadequate WASH facilities.

7. The present writ petition seeks to address this issue of lack of menstrual hygiene management in schools across the country. The problem identified is two-fold, first, absenteeism; and secondly, completely dropping out of school due to lack of MHM measures.2

8. In such circumstances referred to above, the petitioner is here before this Court with the present writ petition.

III. SUBMISSIONS ON BEHALF OF THE PARTIES

i. Submissions on behalf of the Union of India – Respondent Nos. 1 to 3 respectively

9. We have perused the affidavit filed by the Union of India and the concerned Ministries in pursuance of the order dated 24.07.2023 passed by this Court. The respondent nos. 1 to 3 respectively admitted that menstruation and menstrual practices are clouded by taboos and socio-cultural restrictions for women as well as adolescent girls. It was acknowledged that there is a limited access to sanitary products and lack of safe sanitary facilities. It was recognized that unhealthy practices like using old clothes, ash, straw as menstrual absorbent which not only affect menstrual hygiene but also have long-lasting implication on the reproductive health.

10. In pursuance of order dated 06.11.2023, the Union of India through the respondent nos. 1 to 3 respectively, has placed the Menstrual Hygiene Policy for School Going Girls. It is stated that the said policy has been approved by the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. The policy aims to mainstream menstrual hygiene within the Government and Government-aided schools to bolster change in knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour among schoolgirls.

11. The policy intends to provide access to safe and low-cost menstrual hygiene products, environmentally safe disposal methods for menstrual waste, promote clean and gendersegregated sanitation facilities, and incorporate menstrual hygiene education into school curriculum to raise awareness and reduce stigma.

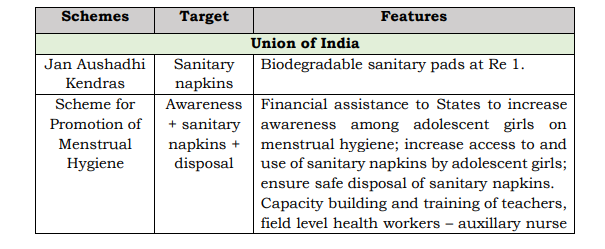

12. In the aforesaid context, the respondent nos. 1 to 3 have undertaken a number of policy initiatives and programmes which are summarized hereinbelow:-

ii. Submissions on behalf of the States – Respondent Nos. 4 to 39 respectively

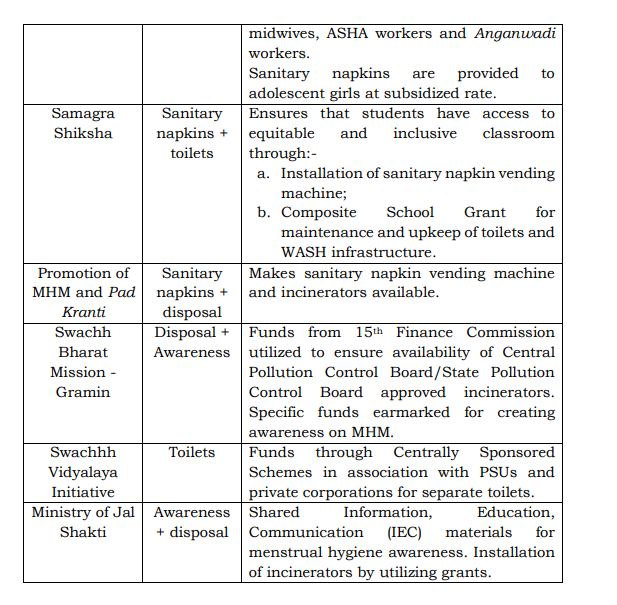

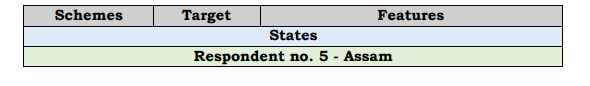

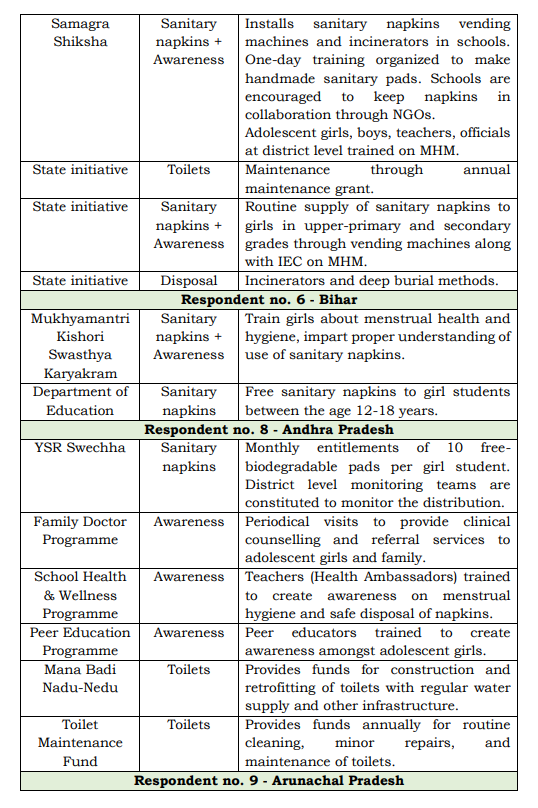

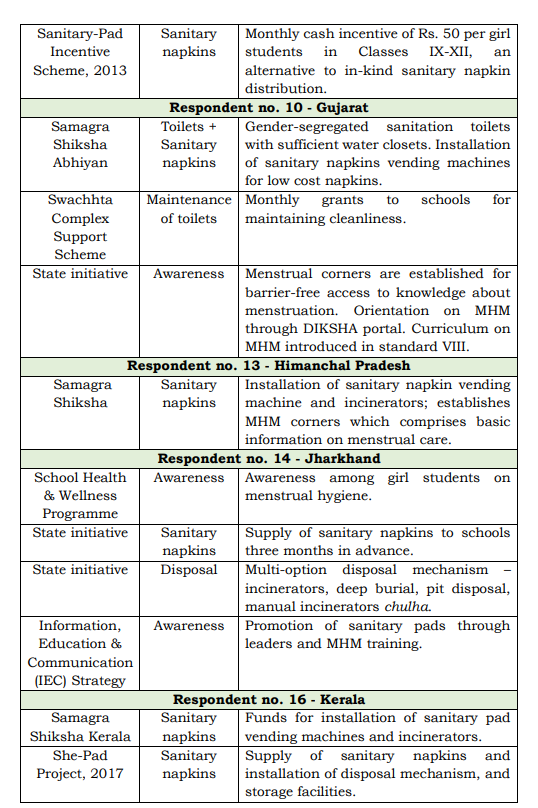

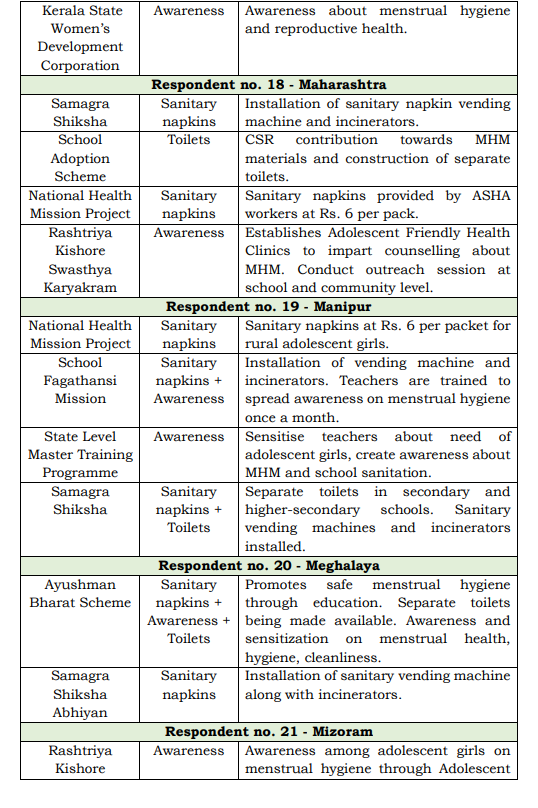

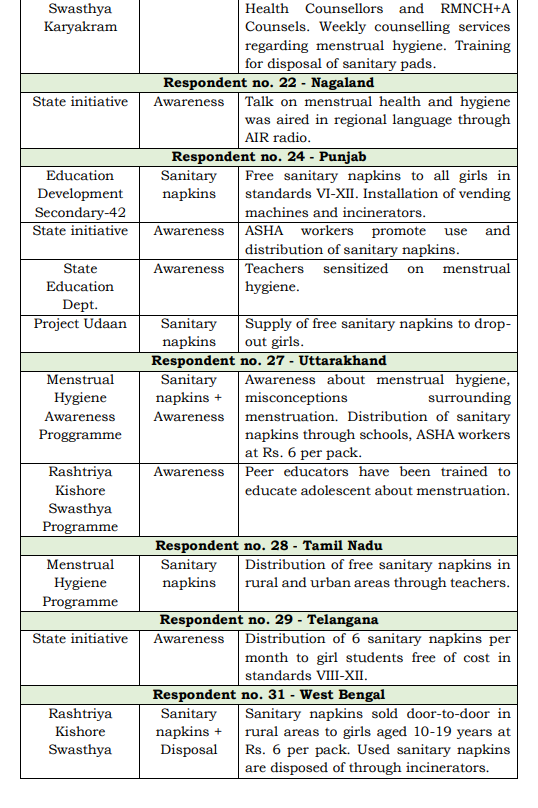

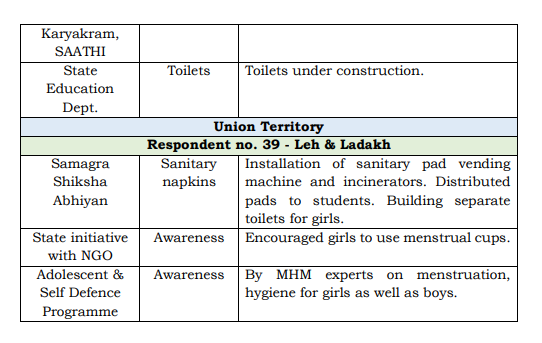

13. The following States have undertaken a number of policy initiatives and programmes which are summarized hereinbelow:-

14. At the same time, the States of Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Goa, Haryana, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Sikkim, Tripura, respectively, and the Union Territories of Delhi, Lakshadweep, Daman & Diu, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Puducherry, Chandigarh, and Jammu & Kashmir respectively have found it convenient to not file their affidavits.

15. Undoubtedly, there is no dearth of policies, schemes, programmes aimed at addressing the issue. However, what seems to be lacking is effective and consistent implementation.

IV. ISSUES FOR CONSIDERATION

16. Having heard the learned counsel appearing for the parties and having gone through the materials placed on record, the following questions fall for our consideration:-

a. Whether unavailability of gender-segregated toilets and nonaccess to menstrual absorbents could be said to be in violation of the right to equality for adolescent girl students under Article 14 of the Constitution?

b. Whether the right to dignified menstrual health could be said to be part of Article 21 of the Constitution?

c. Whether unavailability of gender-segregated toilets and nonaccess to menstrual absorbents could be said to be in violation of the right of participation and equality of opportunity as constitutional guarantees enshrined under Article 14 of the Constitution?

d. Whether unavailability of gender-segregated toilets and nonaccess to menstrual absorbents could be said to be in violation of the right to education under Article 21A, and the right to free and compulsory education under the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009?

V. ANALYSIS

A. The right to access education: A fundamental human right

17. Education is a fundamental human right, as it ensures full and holistic development of a human being. It is a stepping stone towards realizing other human rights. Education is an integral part of dignity of a child. It is a right, not a charitable concession. It promotes the physical and cognitive development of a child. It also contributes to the realization of the full potential of an individual. Most importantly, it shapes a person’s sense of identity and affiliation.

18. A child’s identity, knowledge, values, and skills are largely formed through social relationships. In other words, active participation in community life strengthens their ability to relate to others, promotes inclusivity and harmonious social relations, and facilitates learning through experiences and interactions. To put it briefly, to be educated is to be empowered.

19. It is apposite to understand that the right to education does not exist in a vacuum. Education has a direct impact on an individual’s civil and political rights, cultural rights, and physical and emotional well-being. It influences a person’s ability to make healthier life choices, more particularly, to access and navigate the healthcare system, and to seek timely medical assistance. The right assumes importance in the case of girls, who occupy a comparatively disadvantaged position within familial and societal structures. Undeniably, the way our society perceives women directly translates into prejudice against the girl child, and this perpetuates an endless cycle of discrimination.

20. In the aforesaid context, absence of education limits a girl child’s opportunities for participation and representation in society, restricts her from challenging social hierarchies, and impedes her growth and development. A girl child is often burdened with the weight of social prejudice, stereotypes, and structural oppression that are foisted upon her from an early age. Education serves as a counterweight to these factors by equipping her with knowledge and awareness. In its absence, inequality is not merely sustained but normalized.

i. Education – an essential human right in the International Human Rights Law framework

21. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) recognizes education as a universally protected fundamental human right. It stipulates that everyone has the right to education, and elementary education shall be compulsory. Further, Article 13 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) also recognizes the right to education for everyone. The General Comment on Article 13 of the ICESCR states that the article envisages non-discrimination and equal treatment in imparting education.3To this end, the ICESCR states that State Parties must include policies, programmes, and other practices to identify and take measures to redress any de facto discrimination.

22. Similarly, the Constitution of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) states that the purpose of the Organization is to further respect for human rights and promote equality of educational opportunity. It calls upon the member States to formulate policies aimed at ensuring equality of opportunity and equality of treatment in education. It encourages making primary education free and compulsory, the availability and accessibility of secondary education to all, and the promotion of educational opportunities for persons who have either not received primary education or have been unable to complete it.

23. The UNESCO highlights that the primary purpose of education is to enrich and empower an individual. Education helps shape a person’s understanding of the world, values, and identity. The Organization underscored that education provides for the development of knowledge and skills that helps one negotiate life and achieve goals. It is crucial to interact and shape the world around them. It was referred to as a ‘multiplier right’, meaning that it opens the gate to the enjoyment of other rights.4

24. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) mandates that State Parties take appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of education. It requires that equality must be ensured in access to pre-school, general, technical, professional and higher technical education. The Convention further obligates the State Parties to take effective steps to reduce female student drop-out rates, and actively work towards improving access to educational information necessary to safeguard the health and well-being of families.

25. Similarly, Article 28 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) stipulates that State Parties recognize the right of every child to education. To give meaning to this right, the State Parties are obligated to encourage regular attendance at schools and to reduce drop-out rates. The Convention further mandates that the administration of the school must be in a manner that is consistent with the dignity of the child. In this regard, the State Parties affirm that education must be directed towards the holistic development of the child’s personality, more particularly, mental and physical abilities.

26. The Committee on the Rights of the Child states that discrimination in education violates the human dignity of a child and undermines the capability of a child to benefit from educational opportunities. It states that discriminatory practices include circumstances that limit a girl child’s participation in educational opportunities. It emphasizes that such practices impair a child’s growth to its fullest potential.5

27. What flows from the aforesaid discussion is that while interpreting domestic laws it is important to keep in mind the commitments under various international treaties and interpret laws in a manner consistent with the international human rights standards. Article 51 of the Constitution envisages that the State shall give due regard to international law and treaty obligations.

28. This Court has, time and again, affirmed India’s obligation with regard to international laws and conventions.6 We shall discuss the application of the aforementioned treaties and conventions insofar as the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009 (for short, “the RTE Act”), is concerned in the latter part of this judgment.

ii. Judicial recognition of education as a human right

29. It is necessary for us to look into as to how the courts across the world have recognized the right to education as a basic human right. In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Shawnee County Kan Briggs, reported in 1954 SCC OnLine US SC 44, the Supreme Court of the United States was considering whether segregation of children in schools solely based on race meant depriving the minority group of equal educational opportunities. In this context, the Court highlighted the importance of education. The relevant observations read thus:-

“13. Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship. Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.”

(Emphasis supplied)

30. In Plyler v. J R Doe Texas, reported in 1982 SCC OnLine US SC 118, the issue before the Supreme Court of the United States was whether free public education could be denied to undocumented school-age children. Although access to education was not a constitutional guarantee yet the Court held that the State cannot prevent children from attending public schools unless a substantial state interest is involved. While underscoring the importance of education, it observed that “children denied an education are placed at a permanent and insurmountable competitive disadvantage, for an uneducated child is denied even the opportunity to achieve”. The relevant observations read thus:-

“26. Public education is not a “right” granted to individuals by the Constitution. San Antonio Independent School Dist. v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1, 35, 93 S.Ct. 1278, 1298, 36 L.Ed.2d 16 (1973). But neither is it merely some governmental “benefit” indistinguishable from other forms of social welfare legislation. Both the importance of education in maintaining our basic institutions, and the lasting impact of its deprivation on the life of the child, mark the distinction. The “American people have always regarded education and [the] acquisition of knowledge as matters of supreme importance.” Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 400, 43 S.Ct. 625, 627, 67 L.Ed. 1042 (1923). We have recognized “the public schools as a most vital civic institution for the preservation of a democratic system of government,” Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 230, 83 S.Ct. 1560, 1575, 10 L.Ed.2d 844 (1963) (BRENNAN, J., concurring), and as the primary vehicle for transmitting “the values on which our society rests.” Ambach v. Norwick, 441 U.S. 68, 76, 99 S.Ct. 1589, 1594, 60 L.Ed.2d 49 (1979). “[A]s . . . pointed out early in our history, . . . some degree of education is necessary to prepare citizens to participate effectively and intelligently in our open political system if we are to preserve freedom and independence.” Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 221, 92 S.Ct. 1526, 1536, 32 L.Ed.2d 15 (1972). And these historic “perceptions of the public schools as inculcating fundamental values necessary to the maintenance of a democratic political system have been confirmed by the observations of social scientists.” Ambach v. Norwick, supra, 411 U.S., at 77, 99 S.Ct., at 1594. In addition, education provides the basic tools by which individuals might lead economically productive lives to the benefit of us all. In sum, education has a fundamental role in maintaining the fabric of our society. We cannot ignore the significant social costs borne by our Nation when select groups are denied the means to absorb the values and skills upon which our social order rests.

27. In addition to the pivotal role of education in sustaining our political and cultural heritage, denial of education to some isolated group of children poses an affront to one of the goals of the Equal Protection Clause : the abolition of governmental barriers presenting unreasonable obstacles to advancement on the basis of individual merit. Paradoxically, by depriving the children of any disfavored group of an education, we foreclose the means by which that group might raise the level of esteem in which it is held by the majority. But more directly, “education prepares individuals to be self-reliant and self-sufficient participants in society.” Wisconsin v. Yoder, supra, 406 U.S., at 221, 92 S.Ct., at 1536. Illiteracy is an enduring disability. The inability to read and write will handicap the individual deprived of a basic education each and every day of his life. The inestimable toll of that deprivation on the social economic, intellectual, and psychological well-being of the individual, and the obstacle it poses to individual achievement, make it most difficult to reconcile the cost or the principle of a status-based denial of basic education with the framework of equality embodied in the Equal Protection Clause. [ Because the State does not afford noncitizens the right to vote, and may bar noncitizens from participating in activities at the heart of its political community, appellants argue that denial of a basic education to these children is of less significance than the denial to some other group. Whatever the current status of these children, the courts below concluded that many will remain here permanently and that some indeterminate number will eventually become citizens. The fact that many will not is not decisive, even with respect to the importance of education to participation in core political institutions. “[T]he benefits of education are not reserved to those whose productive utilization of them is a certainty . . . .” 458 F.Supp., at 581, n. 14. In addition, although a noncitizen “may be barred from full involvement in the political arena, he may play a role perhaps even a leadership role—in other areas of import to the community.” Nyquist v. Mauclet, 432 U.S. 1, 12, 97 S.Ct. 2120, 2126, 53 L.Ed.2d 63 (1977).

Moreover, the significance of education to our society is not limited to its political and cultural fruits. The public schools are an important socializing institution, imparting those shared values through which social order and stability are maintained.][…]

xxx

41. Justice MARSHALL, concurring.

42. While I join the Court’s opinion, I do so without in any way retreating from my opinion in San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1, 70-133, 93 S.Ct. 1278, 1315-1348, 36 L.Ed.2d 16 (1973) (dissenting opinion). I continue to believe that an individual’s interest in education is fundamental, and that this view is amply supported “by the unique status accorded public education by our society, and by the close relationship between education and some of our most basic constitutional values.” Id., at 111, 93 S.Ct., at 1336. Furthermore, I believe that the facts of these cases demonstrate the wisdom of rejecting a rigidified approach to equal protection analysis, and of employing an approach that allows for varying levels of scrutiny depending upon “the constitutional and societal importance of the interest adversely affected and the recognized invidiousness of the basis upon which the particular classification is drawn.” Id., at 99, 93 S.Ct., at 1330. See also Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471, 519-521, 90 S.Ct. 1153, 1178-1180, 25 L.Ed.2d 491 (1970) (MARSHALL, J., dissenting). It continues to be my view that a class-based denial of public education is utterly incompatible with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

(Emphasis supplied)

31. In Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India, reported in (1984) 3 SCC 161, a three Judge Bench of this Court held that the right to live with dignity under Article 21 is inspired by the Directive Principles of State Policy which includes, inter alia, educational facilities.

32. We may also refer to the decision in Mohini Jain (Miss) v. State of Karnataka, reported in (1992) 3 SCC 666, wherein this Court held that the right to education forms part of the broader framework of the right to life and human dignity under Article 21 of the Constitution. As the right to life includes the right to live with dignity, such dignity cannot be realized without access to education. While recognizing that denial of education directly impacts the exercise of fundamental rights, the Court observed that social justice cannot be achieved in the absence of education. It observed that education is foundational to the realization of other fundamental rights. The relevant observations read thus:-

“8. The Preamble promises to secure justice “social, economic and political” for the citizens. A peculiar feature of the Indian Constitution is that it combines social and economic rights along with political and justiciable legal rights. The Preamble embodies the goal which the State has to achieve in order to establish social justice and to make the masses free in the positive sense. The securing of social justice has been specifically enjoined an object of the State under Article 38 of the Constitution. Can the objective which has been so prominently pronounced in the Preamble and Article 38 of the Constitution be achieved without providing education to the large majority of citizens who are illiterate. The objectives flowing from the Preamble cannot be achieved and shall remain on paper unless the people in this country are educated. The three-pronged justice promised by the Preamble is only an illusion to the teaming millions who are illiterate. It is only education which equips a citizen to participate in achieving the objectives enshrined in the Preamble. The Preamble further assures the dignity of the individual. The Constitution seeks to achieve this object by guaranteeing fundamental rights to each individual which he can enforce through court of law if necessary. The Directive Principles in Part IV of the Constitution are also with the same objective. The dignity of man is inviolable. It is the duty of the State to respect and protect the same. It is primarily education which brings forth the dignity of a man. The framers of the Constitution were aware that more than seventy per cent of the people, to whom they were giving the Constitution of India, were illiterate. They were also hopeful that within a period of ten years illiteracy would be wiped out from the country. It was with that hope that Articles 41 and 45 were brought in Chapter IV of the Constitution. An individual cannot be assured of human dignity unless his personality is developed and the only way to do that is to educate him. This is why the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 emphasises:“Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality …”. Article 41 in Chapter IV of the Constitution recognises an individual’s right “to education”. It says that “the State shall, within the limits of its economic capacity and development, make effective provision for securing the right … to education …”. Although a citizen cannot enforce the Directive Principles contained in Chapter IV of the Constitution but these were not intended to be mere pious declarations. We may quote the words of Dr Ambedkar in that respect:

“In enacting this Part of the Constitution, the Assembly is giving certain directions to the future legislature and the future executive to show in what manner they are to exercise the legislative and the executive power they will have. Surely it is not the intention to introduce in this Part these principles as mere pious declarations. It is the intention of the Assembly that in future both the legislature and the executive should not merely pay lip service to these principles but that they should be made the basis of all legislative and executive action that they may be taking hereafter in the matter of the governance of the country.”

(C.A.D. Vol. VII, p. 476)”

(Emphasis supplied)

33. A Constitution Bench in Unni Krishnan, J.P. v. State of A.P., reported in (1993) 1 SCC 645, affirmed the abovementioned observations in Mohini Jain (supra) to the extent that the right to education has always been regarded as fundamentally important to human life. The Court observed that the country would be unable to achieve the objectives set forth in the Preamble without education. The relevant observations read thus:-

“Article 21 and Right to Education:

166. In Bandhua Mukti Morcha [(1984) 3 SCC 161 : 1984 SCC (L&S) 389] this Court held that the right to life guaranteed by Article 21 does take in “educational facilities”. (The relevant portion has been quoted hereinbefore.) Having regard to the fundamental significance of education to the life of an individual and the nation, and adopting the reasoning and logic adopted in the earlier decisions of this Court referred to hereinbefore, we hold, agreeing with the statement in Bandhua Mukti Morcha [(1984) 3 SCC 161 : 1984 SCC (L&S) 389] that right to education is implicit in and flows from the right to life guaranteed by Article 21. That the right to education p has been treated as one of transcendental importance in the life of an individual has been recognised not only in this country since thousands of years, but all over the world. In Mohini Jain [Mohini Jain v. State of Karnataka, (1992) 3 SCC 666] the importance of education has been duly and rightly stressed. The relevant observations have already been set out in para 7 hereinbefore. In particular, we agree with the observation that without education being provided to the citizens of this country, the objectives set forth in the Preamble to the Constitution cannot be achieved. The Constitution would fail. We do not think that the importance of education could have been better emphasised than in the above words.[…]”

(Emphasis supplied)

34. Although the 11 judge Bench in T.M.A Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka, reported in (2002) 8 SCC 481, overruled the decision in Unni Krishnan (supra) insofar as the framing of the scheme qua grant of admission and the fixation of the fee, yet the observation that primary education is a fundamental right was affirmed.

35. We may also look into the decision in the case of Minister of Health v. Treatment Action Campaign, reported in 2002 SCC OnLine ZACC 17, wherein the Constitutional Court of South Africa recognized the concept of “minimum core” developed by the ICESR. The minimum core concept ensures that certain essential levels of each right, such as access to basic education, primary healthcare, food, shelter, and dignity, must be guaranteed immediately. The ICESR recognizes that although realization of rights may be subject to resources, yet it obligates State Parties to secure the minimum essential content of the rights.

36. In R.D. Upadhyay v. State of A.P., reported in (2007) 15 SCC 337, a fervent appeal was made to this Court to issue directions for the development of children of those mothers who were either undertrial prisoners or convicts. In such circumstances, this Court directed that adequate arrangements shall be made available in all jails to impart education to children of female prisoners. What has been conveyed by this Court in so many words is the understanding of education as a continuing and non-derogable right that cannot be denied even within the confines of a prison.

37. The Constitutional Court of South Africa in Governing Body of the Juma Musjid Primary School v. Ahmed Asruff Essay N.O., reported in 2011 SCC OnLine ZACC 13, underscored the importance of education in an appeal assailing an order authorizing the eviction of a public school from a private property. To put it in simple words, the Court was addressing a conflict between the right to education and the right to property. While holding that the government has a positive obligation to provide access to schools in fulfilling the right to basic education, the other non-State actors have a negative obligation not to infringe that right under the Constitution. The Court held that any limitation on the right to education must be reasonable and justifiable. The relevant observations read thus:-

“42. The significance of education, in particular basic education [ As enshrined in section 29(1) of the Constitution.] for individual and societal development in our democratic dispensation in the light of the legacy of apartheid, [ As pointed out by Berger in ‘The Rights to Education under the South African Constitution’ (Apr 2003) vol 103, No 3 Columbia Law Review, 616, the separatist national education policy under apartheid, manifested in the Bantu Education Act 47 of 1953, was an integral part of apartheid’s segregationist objective.] cannot be overlooked. The inadequacy of schooling facilities, particularly for many blacks [ Blacks here also denoting Indians and Coloureds.] was entrenched by the formal institution of apartheid, after 1948, when segregation even in education and schools in South Africa was codified. Today, the lasting effects of the educational segregation of apartheid are discernible in the systemic problems of inadequate facilities and the discrepancy in the level of basic education for the majority of learners.

43. Indeed, basic education is an important socioeconomic right directed, among other things, at promoting and developing a child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to his or her fullest potential. [ See also Article 29(1) of the Child Rights Convention, which provides—“States Parties agree that the education of the child shall be directed to:(a) The development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential;(b) The development of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and for the principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations;(c) The development of respect for the child’s parents, his or her own cultural identity, language and values, for the national values of the country in which the child is living, the country from which he or she may originate, and for civilizations different from his or her own;(d) The preparation of the child for responsible life in a free society, in the spirit of understanding, peace, tolerance, equality of sexes, and friendship among all peoples, ethnic, national and religious groups and persons of indigenous origin;(e) The development of respect for the natural environment.”] Basic education also provides a foundation for a child’s lifetime learning and work opportunities. To this end, access to school — an important component of the right to a basic education guaranteed to everyone by section 29(1)(a) of the Constitution — is a necessary condition for the achievement of this right.”

(Emphasis supplied)

38. In the aforesaid context, if a State Party under the ICESR fails to discharge this minimum core obligation, it is considered to be in breach of the Covenant. Moreover, States could justify nonfulfilment of the obligations only by exhibiting that it made everypossible effort to utilize all resources at its disposal to fulfil these obligations. Thus, failure to meet the minimum core threshold deprives the right of its substantive meaning and reduces the right to dead letters.

39. What appears from the aforesaid discussion is that the right to education is not confined to the physical existence or formal availability of schools. It extends to the ability of a child to participate in education in a meaningful, continuous, and nondiscriminatory manner. In other words, mere enrolment does not fulfil the right if structural or practical barriers prevent regular participation, engagement, or progression within the educational system.

40. To enable a child’s participation in school by way of affirmative measures reflects commitment to the substantive approach to equality, which goes beyond formal access to schooling. Such affirmative measures mandate State action to ensure all children are placed equally to avail educational opportunities.

B. Substantive approach to right to equality in education under Article 14 of the Constitution

41. The exercise of the right to education requires the removal of impediments that obstruct its enjoyment. In the present case, these impediments include the lack of MHM measures, such as non-access to toilets, non-availability of menstrual absorbents, and absence of a safe disposal mechanism. These barriers disproportionately affect the right to education of adolescent female students. As a result, the State is under an obligation to address them through appropriate measures.

42. There is no doubt that the right to education loses its spirit if such conditions exist that exclude menstruating girl children from the educational process. As stated aforesaid, addressing the impediments through affirmative actions would be consistent with the substantive approach to equality embodied in Article 14 of the Constitution. In order to place a menstruating girl child on an equal footing with others, mere equal treatment would not suffice.

43. We shall now look into and discuss the substantive approach to the right to equality under Article 14 of the Constitution. Article 14, in its traditional understanding, envisaged formal equality and guaranteed that likes would be treated alike. Under this formal conception of equality, although equality before the law and equal protection of the laws were guaranteed to all, yet inequality in the realization of other rights continued to persist.

44. The principle of substantive equality recognizes that once two individuals are placed in unequal positions because of social, economic, or cultural factors, mere equal “treatment” becomes inadequate. If two individuals are treated alike, without regard to their religion, race, caste, sex, or similar characteristics, the right to equality cannot be given its true effect. In other words, it cannot be given its true effect in the absence of taking into consideration the position of the individual, which may be profoundly shaped by historical and structural disadvantages. Equal treatment afforded in isolation, or rather without accounting for such disadvantage, may perpetuate inequality.

45. Equality is not an abstract concept. It is embedded in social reality and must be responsive to those who are disadvantaged and marginalized. Equality entails not merely formal conferral of rights, but also the adoption of measures necessary to translate those rights into equality.6 Substantive equality is brought into action through policies aiming to redress these systemic, direct or indirect disadvantages, by addressing the structural and contextual barriers that impede genuine equality. To put it briefly, it seeks to reduce the gap between disadvantages and the effective realization of rights.

46. There is no gainsaying that equality cannot be restricted to a mere duty of restraint on the State. Substantive equality can be meaningfully realized only when it is supported by positive overt actions aimed at remedying existing structural disadvantages. In other words, such positive duties require the State to take proactive measures to address patterns of discrimination and exclusion. In the absence of the aforementioned affirmative obligations, structural inequalities are merely preserved, and the promise of equality will be reduced to a paper provision

47. In such circumstances referred to above, differential treatment may be indispensable to achieve equality in practice. As has been aptly observed by Amartya Sen, “Equal consideration for all may demand very unequal treatment in favour of the disadvantaged.”7 As a result, unequal treatment may be constitutionally permissible when it is directed towards securing equal outcomes.8 In other words, substantive equality focuses on the extent to which an individual is able to meaningfully exercise choices, rather than merely possessing a formal right to do so. It recognizes that access to opportunities shall not be constrained by social, economic, or physical factors.

i. Menstruation as a barrier to the right to access education

48. In a research9 conducted on whether schools across the territory of India are menstrual-hygiene friendly, the researchers found that more than half of the girls did not have information about menstruation prior to menarche. The research revealed that the lack of sanitation facilities in schools hindered the ability of girls to manage menstruation healthily, safely, and with dignity.

49. Similarly, the Clean India: Clean Schools Handbook reported that although the number of schools providing drinking water and toilets have increased yet poor maintenance has left them inaccessible. The inaccessibility was attributed to factors such as absence of dedicated funds for operation and maintenance, weak management, poor quality of construction, and the lack of availability of water within toilets.

50. We are disheartened to note that the availability of water for cleaning and flushing of toilets still remains a major concern. The Handbook further reported that MHM is absent in a majority of schools, including the lack of gender-specific infrastructure, access to sanitary napkins, and a disposal mechanism.

51. In another research10 conducted to study school absenteeism during menstruation amongst adolescent school girls in North India, the researchers found that nearly one-third of girls were absent from school due to issues related to menstrual health, restrictive societal norms, and inadequate menstrual hygiene management. Out of approximately 500 students, 29.2% of the participants were reported to be absent from school during menstruation.

52. In the aforesaid study, among the reported reasons for absence, dysmenorrhea11 was the most prevalent, followed by restrictions at home, fear of staining clothes and difficulty in changing sanitary pads at school. The findings of the study revealed that students in government schools were more likely to be absent as compared to those in private schools. Notably, girls using hygienic methods reported lower absenteeism as compared to others. To address the aforesaid issues, the researchers recommended integrating comprehensive menstrual health education into school curricula and improving access to hygienic menstrual products.

53. Accessibility of MHM measures provides the same opportunities for all students in school, while recognizing unequal distribution of resources with the objective to attain equal access to human rights. In other words, it levels the playing field by addressing unequal starting points.

54. The right to education as a human right does not merely demand parity between genders but further requires equality of opportunity in the enjoyment of that right for all. Inaccessibility of MHM measures perpetuates a systemic exclusion and discrimination that impacts the admission or continuation of girl children in school.

55. The observations of this Court in Joseph Shine v. Union of India, reported in (2019) 3 SCC 39, succinctly capture the understanding of the substantive approach to equality. It held that substantive equality is aimed at eliminating all sorts of discrimination that undermine social, economic, and political participation in society. It was further held that Article 15(3) of the Constitution is intended to bring out substantive equality by remedying the disadvantage. It reads thus:-

“171. Section 497 amounts to a denial of substantive equality. The decisions in Sowmithri [Sowmithri Vishnu v. Union of India, 1985 Supp SCC 137 : 1985 SCC (Cri) 325] and Revathi [V. Revathi v. Union of India, (1988) 2 SCC 72 : 1988 SCC (Cri) 308] espoused a formal notion of equality, which is contrary to the constitutional vision of a just social order. Justness postulates equality. In consonance with constitutional morality, substantive equality is “directed at eliminating individual, institutional and systemic discrimination against disadvantaged groups which effectively undermines their full and equal social, economic, political and cultural participation in society” [ S. Martin and K. Mahoney (Eds.), Kathy Lahey, Feminist Theories of (In)equality, in Equality and Judicial Neutrality (1987).] . To move away from a formalistic notion of equality which disregards social realities, the Court must take into account the impact of the rule or provision in the lives of citizens.

172. The primary enquiry to be undertaken by the Court towards the realisation of substantive equality is to determine whether the provision contributes to the subordination of a disadvantaged group of individuals. [ Nivedita Menon (Ed.), Ratna Kapur and Benda Cossman “On Women, Equality and the Constitution : Through the Looking Glass of Feminism in Gender and Politics in India” (1993).] The disadvantage must be addressed not by treating a woman as “weak” but by construing her entitlement to an equal citizenship. The former legitimises patronising attitudes towards women. The latter links true equality to the realisation of dignity. The focus of such an approach is not simply on equal treatment under the law, but rather on the real impact of the legislation. [ Maureen Maloney, “An Analysis of Direct Taxes in India : A Feminist Perspective”, Journal of the Indian Law Institute (1988).] Thus, Section 497 has to be examined in the light of existing social structures which enforce the position of a woman as an unequal participant in a marriage.”

(Emphasis supplied)

56. By yet another Constitution Bench of this Court in Janhit Abhiyan v. Union of India (EWS Reservation), reported in (2023) 5 SCC 1, it was held that when substantive equality is asserted as a constitutional mandate, the State is tasked to place the concerned individuals on an equal footing. This Court, in so many words, held that substantive equality can take various forms, as per the requirements of the disadvantaged person or group. It was also observed that social justice cannot be achieved without substantive equality which means taking affirmative actions. The relevant observations read thus:-

“87. Indian constitutional jurisprudence has consistently held the guarantee of equality to be substantive and not a mere formalistic requirement. Equality is at the nucleus of the unified goals of social and economic justice. In Minerva Mills [Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India, (1980) 3 SCC 625] it was observed : (SCC p. 709, para 111)

“111. … the equality clause in the Constitution does not speak of mere formal equality before the law but embodies the concept of real and substantive equality which strikes at inequalities arising on account of vast social and economic differentials and is consequently an essential ingredient of social and economic justice. The dynamic principle of egalitarianism fertilises the concept of social and economic justice; it is one of its essential elements and there can be no real social and economic justice where there is a breach of the egalitarian principle.”

(emphasis supplied)

88. Thus, equality is a feature fundamental to our Constitution but, in true sense of terms, equality envisaged by our Constitution as a component of social, economic and political justice is real and substantive equality, which is to organically and dynamically operate against all forms of inequalities. This process of striking at inequalities, by its very nature, calls for reasonable classifications so that equals are treated equally while unequals are treated differently and as per their requirements.

xxx

99. Thus, it could reasonably be summarised that for the socio-economic structure which the law in our democracy seeks to build up, the requirements of real and substantive equality call for affirmative actions; and reservation is recognised as one such affirmative action, which is permissible under the Constitution; and its operation is defined by a large number of decisions of this Court, running up to the detailed expositions in Jaishri Patil [Jaishri Laxmanrao Patil v. State of Maharashtra, (2021) 8 SCC 1] .”

(Emphasis supplied)

57. We may refer with profit the decision in Gaurav Kumar v. Union of India, reported in (2025) 1 SCC 641, wherein one of us, J.B. Pardiwala, J., was a part of the Bench, this Court reiterated that the substantive approach to equality aims to eliminate individual, institutional, and systemic discrimination against the disadvantaged. To put it briefly, substantive equality can be achieved through affirmative actions aimed towards eliminating discriminatory factors.

58. Recently, in Jane Kaushik v. Union of India, reported in (2026) 1 SCC 336, this Bench held that redressal of a disadvantage cannot be devoid of an understanding of the other impediments that an individual may face on account of other identity markers that may cause such an individual to be stigmatized and marginalized. The principle of reasonable accommodation was put into application as a means for achieving substantive equality.

a. Intersectionality of disability, gender, and access to education

59. The responsibility of the State is further heightened in the case of a child with disability, as the intersection of disability with gender compounds the disadvantage faced during menstruation. In case of children with disabilities, accessibility of washrooms is even more essential for inclusion and for enabling meaningful participation in school. Needless to say, the absence of such accessibility results in exclusion from education and reinforces the social and economic marginalization.

60. In Rajiv Raturi v. Union of India, reported in (2024) 16 SCC 654, wherein one of us, J. B. Pardiwala, J., was a part of the Bench, held that the right to accessibility is an integral part of the existing human right framework, more particularly, of Articles 14, 19, and 21 respectively. It was observed that accessibility enables the exercise of other rights, one of which forms part of the right to live a meaningful life under Article 21. The Court further held that to enable such a right the State is required to implement accessibility measures proactively. The relevant observations read thus:-

“22. Accessibility is not merely a convenience, but a fundamental requirement for enabling individuals, particularly those with disabilities, to exercise their rights fully and equally. Without accessibility, individuals are effectively excluded from many aspects of society, whether that be education, employment, healthcare, or participation in cultural and civic activities. Accessibility ensures that persons with disabilities are not marginalised but are instead able to enjoy the same opportunities as everyone else, making it an integral part of ensuring equality, freedom, and human dignity. By embedding accessibility as a human right within existing legal frameworks, it becomes clear that it is an essential prerequisite for the exercise of other rights.

xxx

26. Similarly, A.K. Sikri, J. in the 2017 judgment [Rajive Raturi v. Union of India, (2018) 2 SCC 413 : (2018) 1 SCC (L&S) 404] grounded the right to accessibility in the fundamental rights chapter of the Constitution, emphasizing that access to public spaces and services is an essential aspect of the right to life and dignity. This Court observed: (SCC p. 426, para 12)

“12. The vitality of the issue of “accessibility” vis-àvis visually disabled person’s right to life can be gauged clearly by the [Supreme] Court’s judgment in State of H.P. v. Umed Ram Sharma [State of H.P. v. Umed Ram Sharma, (1986) 2 SCC 68] where the right to life under Article 21 has been held broad enough to incorporate the right to accessibility.”

27. The inclusion of accessibility within the fundamental rights framework ensures that PWDs are entitled to full participation in society under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution. Article 14 upholds equal access to spaces, services, and information; Article 19 guarantees the freedom to move and express oneself; and Article 21 ensures the right to live with dignity. Together, these provisions guarantee not only formal equality but also substantive equality, which requires the State to take positive steps to ensure that individuals can enjoy their rights fully, irrespective of disabilities. This Court in a plethora of judgments has repeatedly recognised that the right to dignity and the right to a meaningful life under Article 21 necessitate conditions that enable PWDs to enjoy the same freedoms and choices as others. [ See Jeeja Ghosh v. Union of India, (2016) 7 SCC 761 : (2016) 3 SCC (Civ) 551 : 2016 INSC 412; Rajive Raturi v. Union of India, (2018) 2 SCC 413 : (2018) 1 SCC (L&S) 404 : 2017 INSC 1243; Ravinder Kumar Dhariwal v. Union of India, (2023) 2 SCC 209 : (2023) 1 SCC (L&S) 181 : 2021 INSC 916; Vikash Kumar v. UPSC, (2021) 5 SCC 370 : (2021) 2 SCC (L&S) 1 : 2021 INSC 78.] Thus, the right to accessibility is foundational, enabling PWDs to exercise and benefit from other rights enshrined in Part III of the Constitution.”

(Emphasis supplied)

61. We would like to refer to the observations of this Court in Om Rathod v. Director General of Health Services, reported in 2024 SCC OnLine SC 3130, to further elaborate upon the principles of law on substantive equality in disability rights. It was observed that Section 3 of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, casts a positive obligation on the State as well as private entities to ensure that no person with disability faces discrimination. The Court held that reasonable accommodation is a facet of substantive equality and failure to reasonably accommodate constitutes discrimination. The relevant observations read thus:-

“29. The principle of reasonable accommodation is not only statutorily prescribed but also rooted in the fundamental rights guaranteed to persons with disabilities under Part III of the Constitution. Reasonable accommodation is a fundamental right. It is a gateway right for persons with disabilities to enjoy all the other rights enshrined in the Constitution and the law. Without the gateway right of reasonable accommodation, a person with disability is forced to navigate in a world which excludes them by design. It strikes a fatal blow to their ability to make life choices and pursue opportunities. From mundane tasks of daily life to actions undertaken to realise personal and professional aspirations – all are throttled when reasonable accommodations are denied. Reasonable accommodation is a facet of substantive equality and its failure constitutes discrimination.[…]”

30. Section 3 of the RPWD Act affords persons with disabilities a right to equality and non-discrimination. In Vikash Kumar (supra) this Court held that Section 3 casts an affirmative obligation on the Government and private entities to take steps to ensure reasonable accommodation and utilize the capacity of persons with disabilities by providing an appropriate environment. There is a positive obligation to realise the inclusive premise in the concept of reasonable accommodation. This includes the duty to create an environment conducive for the development of persons with disabilities. This Court has held that:

“… The accommodation which the law mandates is ‘reasonable’ because it has to be tailored to the requirements of each condition of disability. The expectations which every disabled person has are unique to the nature of the disability and the character of the impediments which are encountered as its consequence. …

48. Failure to meet the individual needs of every disabled person will breach the norm of reasonable accommodation. Flexibility in answering individual needs and requirements is essential to reasonable accommodation. The principle of reasonable accommodation must also account for the fact that disability based discrimination is intersectional in nature. The intersectional features arise in particular contexts due to the presence of multiple disabilities and multiple consequences arising from disability. Disability therefore cannot be truly understood by regarding it as unidimensional.” (emphasis supplied)”

(Emphasis supplied)

62. Although accessibility and reasonable accommodation are distinct concepts, as already recognized in Rajive Raturi v. Union of India, reported in (2024) 16 SCC 654, yet the foundation for both is a substantive approach to equality and removal of barriers that impede the effective realization of rights. To put this in context, a commitment to accessibility would reflect in making the washrooms at school accessible for children with disabilities. However, this is not enough, reasonably accommodating a girl child with disability would also mean making menstrual absorbents available and educating all the students about menstruation and MHM measures.

63. Thus, we have no hesitation in saying that inaccessibility means not only depriving a girl child with disability of education but also violating her right to equality, freedom, and dignity. To reasonably accommodate means actively creating a conducive environment for children with disabilities.

64. What can be discerned from the above discussion is that the steps towards substantive equality are, first, the identification and recognition of disadvantage; and secondly, actions taken towards redressing that disadvantage. This Court is mindful that constitutional guarantees do not attain their true meaning by mere textual inclusion in statute books but through their realization in reality.

65. For a menstruating girl child who cannot afford menstrual absorbents, the disadvantage is two-fold. First, vis-à-vis menstruating girl children who can afford menstrual absorbents. Secondly, vis-à-vis male counterparts or nonmenstruating counterparts. Further, when the menstruating girl child is also a child with disability, she is not merely facing disadvantages arising from menstrual poverty, but is additionally subjected to other disadvantageous consequences flowing from the intersection of gender and disability.

66. The aforesaid disadvantages can be redressed by ensuring access to clean gender-segregated washrooms, sanitary napkins, or other suitable menstrual absorbents, hygienic and safe disposal mechanisms; and spreading awareness and imparting education on menstruation and MHM measures.

67. The right to education is a universally recognized human right, which, in circumstances referred to above, stands compromised and undermined for girl children. Menstrual poverty hinders menstruating girls from exercising their right to education with dignity equal to that of their male counterparts, or students who can afford sanitary products. There is no gainsaying that impairment of primary or secondary education has grave and lasting consequences, not only for individual development but also for long-term social and economic participation.

68. Many girls choose to absent themselves during menstruation due to lack of access to, or inability to afford, menstrual hygiene products, unavailability of gender-segregated washrooms, and absence of disposal mechanisms. This establishes a clear causal relationship between menstrual poverty and girls’ lower attendance in school. The absence of such measures lead many girls to absent themselves, or rather drop-out of school, leaving a lasting adverse impact on their education.

C. The right to dignified menstrual health a part of Article 21

i. The right to human dignity as a concomitant of the right to life

69. The right to life under Article 21 means a life with dignity. This Court, in a catena of decisions, has consistently recognized that dignity is an essential and inseparable facet of the right to life and liberty. The right to life means more than mere survival. Every human possesses inherent dignity by virtue of being human, which enables the individual to make self-determining choices. This Court has recognized dignity to be intrinsic and inalienable continuing beyond biological existence.12

70. When we recognize dignity as forming a significant part of human existence, we acknowledge the value of life. Dignity makes life livable. There is no gainsaying to the fact that the right to a dignified existence secures decisional autonomy, enabling an individual to transform life from mere subsistence into a meaningful endeavour. Dignity inheres in every stage and every aspect of human existence. As a result, the Constitution protects an individual’s expectation that dignity will be preserved and respected throughout their life.

71. In this regard, we shall refer to the decision in K.S. Puttaswamy (Privacy-9 J.) v. Union of India, reported in (2017) 10 SCC 1, wherein this Court categorically held that dignity is an integral part of the Constitution, and its reflections are found in Articles 14, 19, and 21, respectively. This Court noted that dignity can neither be given nor taken away. It held that there is a positive obligation on the State to not only protect one’s dignity but also take steps to facilitate it. It was observed that dignity ties all the fundamental rights together. The relevant observations read thus:-

“Jurisprudence on dignity 108. Over the last four decades, our constitutional jurisprudence has recognised the inseparable relationship between protection of life and liberty with dignity. Dignity as a constitutional value finds expression in the Preamble. The constitutional vision seeks the realisation of justice (social, economic and political); liberty (of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship); equality (as a guarantee against arbitrary treatment of individuals) and fraternity (which assures a life of dignity to every individual). These constitutional precepts exist in unity to facilitate a humane and compassionate society. The individual is the focal point of the Constitution because it is in the realisation of individual rights that the collective wellbeing of the community is determined. Human dignity is an integral part of the Constitution. Reflections of dignity are found in the guarantee against arbitrariness (Article 14), the lamps of freedom (Article 19) and in the right to life and personal liberty (Article 21).

xxx

113. Human dignity was construed in M. Nagaraj v. Union of India [M. Nagaraj v. Union of India, (2006) 8 SCC 212 : (2007) 1 SCC (L&S) 1013] by a Constitution Bench of this Court to be intrinsic to and inseparable from human existence. Dignity, the Court held, is not something which is conferred and which can be taken away, because it is inalienable : (SCC pp. 243 & 247-48, paras 26 & 42)

“26. … The rights, liberties and freedoms of the individual are not only to be protected against the State, they should be facilitated by it. … It is the duty of the State not only to protect the human dignity but to facilitate it by taking positive steps in that direction. No exact definition of human dignity exists. It refers to the intrinsic value of every human being, which is to be respected. It cannot be taken away. It cannot give (sic be given). It simply is. Every human being has dignity by virtue of his existence. …

***

42. India is constituted into a sovereign, democratic republic to secure to all its citizens, fraternity assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity of the nation. The sovereign, democratic republic exists to promote fraternity and the dignity of the individual citizen and to secure to the citizens certain rights. This is because the objectives of the State can be realised only in and through the individuals. Therefore, rights conferred on citizens and non-citizens are not merely individual or personal rights. They have a large social and political content, because the objectives of the Constitution cannot be otherwise realised.”

(emphasis supplied)

119. To live is to live with dignity. The draftsmen of the Constitution defined their vision of the society in which constitutional values would be attained by emphasising, among other freedoms, liberty and dignity. So fundamental is dignity that it permeates the core of the rights guaranteed to the individual by Part III. Dignity is the core which unites the fundamental rights because the fundamental rights seek to achieve for each individual the dignity of existence. Privacy with its attendant values assures dignity to the individual and it is only when life can be enjoyed with dignity can liberty be of true substance. Privacy ensures the fulfilment of dignity and is a core value which the protection of life and liberty is intended to achieve.”

(Emphasis supplied)

72. In Common Cause v. Union of India, reported in (2018) 5 SCC 1, Chandrachud, J., opined that the Constitution protects the legitimate expectation of a person to live a life with dignity. The relevant observations read thus:-

“437. Under our Constitution, the inherent value which sanctifies life is the dignity of existence. Recognising human dignity is intrinsic to preserving the sanctity of life. Life is truly sanctified when it is lived with dignity. There exists a close relationship between dignity and the quality of life. For, it is only when life can be lived with a true sense of quality that the dignity of human existence is fully realised. Hence, there should be no antagonism between the sanctity of human life on the one hand and the dignity and quality of life on the other hand. Quality of life ensures dignity of living and dignity is but a process in realising the sanctity of life.

438. Human dignity is an essential element of a meaningful existence. A life of dignity comprehends all stages of living including the final stage which leads to the end of life. Liberty and autonomy are essential attributes of a life of substance. It is liberty which enables an individual to decide upon those matters which are central to the pursuit of a meaningful existence. The expectation that the individual should not be deprived of his or her dignity in the final stage of life gives expression to the central expectation of a fading life : control over pain and suffering and the ability to determine the treatment which the individual should receive. When society assures to each individual a protection against being subjected to degrading treatment in the process of dying, it seeks to assure basic human dignity. Dignity ensures the sanctity of life. The recognition afforded to the autonomy of the individual in matters relating to endof-life decisions is ultimately a step towards ensuring that life does not despair of dignity as it ebbs away.

xxx

518. Constitutional recognition of the dignity of existence as an inseparable element of the right to life necessarily means that dignity attaches throughout the life of the individual. Every individual has a constitutionally protected expectation that the dignity which attaches to life must subsist even in the culminating phase of human existence. Dignity of life must encompass dignity in the stages of living which lead up to the end of life. Dignity in the process of dying is as much a part of the right to life under Article 21. To deprive an individual of dignity towards the end of life is to deprive the individual of a meaningful existence. Hence, the Constitution protects the legitimate expectation of every person to lead a life of dignity until death occurs;”

(Emphasis supplied)

73. Recently, in Gaurav Kumar v. Union of India, reported in (2025) 1 SCC 641, wherein one of us, J.B. Pardiwala, J., was a part of the Bench, this Court elucidated the importance of dignity in achieving substantive equality. This Court held that dignity encompasses the right of the individual to develop their potential to the fullest. The relevant observations read thus:-

“99. Dignity is crucial to substantive equality. The dignity of an individual encompasses the right of the individual to develop their potential to the fullest. [K.S. Puttaswamy (Privacy-9 J.) v. Union of India, (2017) 10 SCC 1, para 525] The right to pursue a profession of one’s choice and earn livelihood is integral to the dignity of an individual. Charging exorbitant enrolment fees and miscellaneous fees as a precondition for enrolment creates a barrier to entry into the legal profession. The levy of exorbitant fees as a precondition to enrolment serves to denigrate the dignity of those who face social and economic barriers in the advancement of their legal careers. [ See Neil Aurelio Nunes (OBC Reservation) v. Union of India, (2022) 4 SCC 1, para 35] This effectively perpetuates systemic discrimination against persons from marginalised and economically weaker sections by undermining their equal participation in the legal profession. Therefore, the current enrolment fee structure charged by SBCs is contrary to the principle of substantive equality.”

(Emphasis supplied)

74. In our considered view, MHM measures are inseparable from the right to live with dignity under Article 21. We say so because dignity cannot be reduced to an abstract ideal, it must find expression in conditions that enable individuals to live without humiliation, exclusion, or avoidable suffering. For menstruating girl children, the inaccessibility of MHM measures subjects them to stigma, stereotyping, and humiliation.

75. The absence of safe and hygienic menstrual management measures undermines dignified existence by compelling the adolescent female students to either resort to absenteeism or adopt unsafe practices, or both, which violates the bodily autonomy of the menstruating girl children.

ii. The right to privacy and decisional autonomy

76. Dignity cannot be assured without privacy. Privacy is one of the rights that are inherent in a human being by virtue of mere existence. Being a natural right, it inures every individual irrespective of their caste, class, gender, or any other similar differentiating ground. Privacy enables each individual to make choices and take decisions in respect of intimate and personal matters, free from interference. It is this conception of natural and inalienable right that secures the autonomy of human being.

77. In Puttaswamy (supra), this Court held the right to privacy to be a constitutionally protected right under Article 21. It recognized privacy as a natural right which is inherent in a human and not bestowed by the State. It was observed that privacy ensures the fulfilment of dignity and is a core value which protection of life and liberty has intended to achieve. In furtherance of this constitutional protection, the Court held that it is the duty of the State to safeguard the autonomy of an individual. The relevant observations read thus:-

“G. Natural and inalienable rights

42. Privacy is a concomitant of the right of the individual to exercise control over his or her personality. It finds an origin in the notion that there are certain rights which are natural to or inherent in a human being. Natural rights are inalienable because they are inseparable from the human personality. The human element in life is impossible to conceive without the existence of natural rights. In 1690, John Locke had in his Second Treatise of Government observed that the lives, liberties and estates of individuals are as a matter of fundamental natural law, a private preserve. The idea of a private preserve was to create barriers from outside interference. In 1765, William Blackstone in his Commentaries on the Laws of England spoke of a “natural liberty”. There were, in his view, absolute rights which were vested in the individual by the immutable laws of nature. These absolute rights were divided into rights of personal security, personal liberty and property. The right of personal security involved a legal and uninterrupted enjoyment of life, limbs, body, health and reputation by an individual.

xxx

46. Natural rights are not bestowed by the State. They inhere in human beings because they are human. They exist equally in the individual irrespective of class or strata, gender or orientation.

xxx

118. Life is precious in itself. But life is worth living because of the freedoms which enable each individual to live life as it should be lived. The best decisions on how life should be lived are entrusted to the individual. They are continuously shaped by the social milieu in which individuals exist. The duty of the State is to safeguard the ability to take decisions — the autonomy of the individual — and not to dictate those decisions. “Life” within the meaning of Article 21 is not confined to the integrity of the physical body. The right comprehends one’s being in its fullest sense. That which facilitates the fulfilment of life is as much within the protection of the guarantee of life.

xxx

320. Privacy is a constitutionally protected right which emerges primarily from the guarantee of life and personal liberty in Article 21 of the Constitution.

Elements of privacy also arise in varying contexts from the other facets of freedom and dignity recognised and guaranteed by the fundamental rights contained in Part III.”

(Emphasis supplied)

78. Bobde, J., in his concurring opinion in Puttaswamy (supra), stated that privacy is a prerequisite for the exercise of liberty and the freedom to perform any activity. Consequently, the absence of privacy denies an individual the freedom to exercise that particular liberty or to undertake such activity. Similarly, Nariman, J., recognized the privacy of choice as an individual’s autonomy over fundamental choices.

79. As a sequitur, autonomy is a concomitant of privacy. We say so because privacy is founded on the autonomy of an individual. At the same time, dignity cannot exist without privacy. In Puttaswamy (supra), this Court defined autonomy as “the ability to make decision on vital matters of concern to life”. While lucidly elucidating facets of privacy, this Court recognized an individual’s authority to make decisions as regards their body and mind. Further, while identifying the various facets of privacy, the Court recognized decisional privacy to mean the ability of an individual to make intimate decisions, including those relating to sexual autonomy. The relevant observations read thus:-

“297. What, then, does privacy postulate? Privacy postulates the reservation of a private space for the individual, described as the right to be let alone. The concept is founded on the autonomy of the individual. The ability of an individual to make choices lies at the core of the human personality. The notion of privacy enables the individual to assert and control the human element which is inseparable from the personality of the individual. The inviolable nature of the human personality is manifested in the ability to make decisions on matters intimate to human life. The autonomy of the individual is associated over matters which can be kept private. These are concerns over which there is a legitimate expectation of privacy. The body and the mind are inseparable elements of the human personality. The integrity of the body and the sanctity of the mind can exist on the foundation that each individual possesses an inalienable ability and right to preserve a private space in which the human personality can develop. Without the ability to make choices, the inviolability of the personality would be in doubt. Recognising a zone of privacy is but an acknowledgment that each individual must be entitled to chart and pursue the course of development of personality. Hence privacy is a postulate of human dignity itself. Thoughts and behavioural patterns which are intimate to an individual are entitled to a zone of privacy where one is free of social expectations. In that zone of privacy, an individual is not judged by others. Privacy enables each individual to take crucial decisions which find expression in the human personality. It enables individuals to preserve their beliefs, thoughts, expressions, ideas, ideologies, preferences and choices against societal demands of homogeneity. Privacy is an intrinsic recognition of heterogeneity, of the right of the individual to be different and to stand against the tide of conformity in creating a zone of solitude. Privacy protects the individual from the searching glare of publicity in matters which are personal to his or her life. Privacy attaches to the person and not to the place where it is associated. Privacy constitutes the foundation of all liberty because it is in privacy that the individual can decide how liberty is best exercised. Individual dignity and privacy are inextricably linked in a pattern woven out of a thread of diversity into the fabric of a plural culture.

298. Privacy of the individual is an essential aspect of dignity. Dignity has both an intrinsic and instrumental value. As an intrinsic value, human dignity is an entitlement or a constitutionally protected interest in itself. In its instrumental facet, dignity and freedom are inseparably intertwined, each being a facilitative tool to achieve the other. The ability of the individual to protect a zone of privacy enables the realisation of the full value of life and liberty. Liberty has a broader meaning of which privacy is a subset. All liberties may not be exercised in privacy. Yet others can be fulfilled only within a private space. Privacy enables the individual to retain the autonomy of the body and mind. The autonomy of the individual is the ability to make decisions on vital matters of concern to life. Privacy has not been couched as an independent fundamental right. But that does not detract from the constitutional protection afforded to it, once the true nature of privacy and its relationship with those fundamental rights which are expressly protected is understood. Privacy lies across the spectrum of protected freedoms. […] Above all, the privacy of the individual recognises an inviolable right to determine how freedom shall be exercised. […] Read in conjunction with Article 21, liberty enables the individual to have a choice of preferences on various facets of life including what and how one will eat, the way one will dress, the faith one will espouse and a myriad other matters on which autonomy and self-determination require a choice to be made within the privacy of the mind. […] Dignity cannot exist without privacy. Both reside within the inalienable values of life, liberty and freedom which the Constitution has recognised. Privacy is the ultimate expression of the sanctity of the individual. It is a constitutional value which straddles across the spectrum of fundamental rights and protects for the individual a zone of choice and self-determination.”

80. In this regard, in Common Cause (supra), this Court held thus:-