Disclosure of Criminal Antecedents as Ground for Disqualification

Poonam v Dule Singh

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that the non-disclosure of criminal antecedents is not a ground for disqualification of an election, unless it materially affected the results. The Petitioner was disqualified from holding the post of Councillor due to the non-disclosure of a previous conviction under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881.

...

Case Details

Judgement Date: 6 November 2025

Citations: 2025 INSC 1284 | 2025 SCO.LR 11(2)[8]

Bench: P.S. Narasimha J, A.S. Chandurkar J

Keyphrases: Electoral disqualification—Non-disclosure of criminal antecedents—Conviction under Section 138 NI Act—Voters' right to know—Need to prove material effect—SLP dismissed.

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

ATUL S. CHANDURKAR, J.

1. The petitioner suffered a conviction under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881. She, however, failed to disclose her conviction in the nomination form for the election to the post of Councillor. Her election was challenged by the first respondent, and the trial Court unseated her from the post of Councillor holding her to be disqualified under the provisions of The Madhya Pradesh Municipalities Act, 1961. The revision application preferred by the petitioner having been dismissed, she has preferred the present Special Leave Petition.

2. In the elections held for the post of Councillor at Nagar Parishad, Bhikangaon, the petitioner came to be elected from Ward No.5 securing the highest number of votes. Notification to that effect dated 04.10.2022 came to be issued. The first respondent filed an election petition under Section 20 of the Madhya Pradesh Municipalities Act, 1961 (hereinafter, “the Act of 1961”) read with The Madhya Pradesh Nagar Palika Nirvachan Niyam, 1994 (hereinafter “the Rules of 1994”) and sought a declaration that the petitioner be held disqualified for holding the post of Councillor and that her seat be declared as vacant. In the election petition, it was pleaded by the first respondent that on 07.08.2018, the petitioner had been convicted in proceedings filed under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 (hereinafter, “the Act of 1881”). She had been sentenced to suffer rigorous imprisonment for a period of one year and also ordered to pay compensation. The fact of her conviction, however, had not been disclosed by the petitioner in the affidavit filed along with the nomination form as required by Rule 24-A of the Rules of 1994. Though other grounds of challenge were also raised, same are not relevant for the present purpose. It was thus prayed that the petitioner be declared disqualified from holding the post of Councillor.

3. The petitioner filed her reply and opposed the election petition by raising a plea that the order of conviction dated 07.08.2018 was no longer in existence as the same had set aside in appeal. She stated that the election petition was liable to be dismissed as she had not incurred any disqualification as mentioned in Section 35 of the Act of 1961.

4. The parties led evidence before the trial Court and after considering the same, the learned Judge of the trial Court held that the petitioner had been convicted under Section 138 of the Act of 1881 which fact had not been disclosed in the affidavit filed along with the nomination form. It was further held that since it was mandatory on the part of a candidate to disclose if he/she had suffered any conviction, the voters had a right to obtain correct information. As the conviction of the petitioner was not mentioned in her affidavit, it was clear that this had affected the voters from Ward No.5. The election of the petitioner was held to be materially affected. It was thus concluded that since the petitioner failed to disclose the fact of her conviction in her affidavit, she was disqualified from continuing as a Councillor. By the judgment dated 17.02.2025, the election of the petitioner was set aside holding her to be disqualified for holding the post of Councillor from Ward No.5. Her election was declared null and void.

5. The petitioner being aggrieved by her disqualification challenged the same by filing a revision application before the High Court under Section 26 (2) of the Act of 1961. One of the contentions raised on behalf of the petitioner was that the order of conviction had been set aside on 30.12.2022 and hence the same could not be the basis for unseating her. It was also urged that the first respondent had failed to prove that the election of the petitioner had been materially affected on account of non-compliance of the provisions of Rule 24-A of the Rules of 1994. The learned Judge of the High Court held that the petitioner had failed to disclose the fact of her conviction in her affidavit filed along with the nomination form. This resulted in breach of Rules 24-A of the Rules of 1994. Consequently, the provisions of Section 22(1) (d) (iii) of the Act of 1961 were attracted and the same was the ground for declaring the election of the petitioner to be void. While arriving at this finding, it was observed that the petitioner did not enter into the witness box to establish that by failing to disclose her conviction, her election was not materially affected nor did it influence the election. The judgment of the trial Court was thus upheld by recording a finding that by failing to disclose her conviction in the affidavit filed along with nomination form, there was a breach of Rule 24-A of the Rules of 1994 and the petitioner’s election was rightly set aside. The revision application was thus dismissed. Being aggrieved, the petitioner has approached this Court under Article 136 of the Constitution of India

6. Mr. Vivek Tankha, learned Senior Advocate for the petitioner made the following submissions:

a. The election of the petitioner was wrongly declared as null and void. Assuming that there was a failure on the part of the petitioner to disclose her conviction under Section 138 of the Act of 1881, it could not be said that such nondisclosure was of a substantial nature that would affect the outcome of the election for it to be set aside. The conviction was for an offence not involving moral turpitude and therefore such non-disclosure was not of a material nature. The offence being compoundable in nature and the conviction of the petitioner having been subsequently set aside, no material difference could be stated to have been made on account of non-disclosure of such conviction in the affidavit. To substantiate this contention the learned Senior Advocate placed reliance on the decisions in Ravi Namboothiri vs. K.A. Baiju & others1 and Karikho Krivs. Nuney Tayang and another2. It was thus urged that the election of the petitioner having been wrongly set aside, she was liable to be restored to her elected post.

b. The first respondent (election petitioner) had failed to prove that the election of the petitioner as a returned candidate had been materially affected on account of non-disclosure of her conviction in the affidavit filed along with the nomination form. Hence, her election could not have been set aside under Section 22 (1) (d) (i) or (iii) of the Act of 1961. There were no pleadings in the election petition that by the improper acceptance of the petitioner’s nomination form or on account of non-compliance of the provisions of Rule 24-A of the Rules of 1994, the election of the petitioner had been materially affected. This material aspect was not taken into consideration while unseating the petitioner.

7. On the other hand, Mr. Sarvam Ritam Khare, learned Advocate appearing for the first respondent opposed the appeal by urging as under:

a. The fact that the petitioner had been convicted for the offence punishable under Section 138 of the Act of 1881 not having been disclosed in the affidavit required to be filed under Rule 24-A of the Rules of 1994, it was clear that the nomination form of the petitioner was wrongly accepted in breach of Section 22 (1) (d) (i) of the Act of 1961. There had also been non-compliance with the requirements of the Act of 1961 and the Rules of 1994 thereby affecting the petitioner’s nomination. On this count, the election of the petitioner had been rightly set aside. In support of this submission the learned Advocate placed reliance on the decisions in Resurgence India Vs. Election Commission of India and another3 and Krishnamoorthy Vs. Shivakumar and others.4

b. Since the petitioner was convicted on 07.08.2018 and the said conviction continued to operate when the nomination form was filed, the subsequent acquittal of the petitioner on 30.12.2022 after the elections were held was of no consequence. The eligibility of a candidate was required to be determined as on the date of submission of the nomination form. Both the Courts had rightly found that the conviction of the petitioner was operating when she had submitted the nomination form.

c. After the election of the petitioner was set aside, fresh elections were held to fill in the vacancy as caused. The petitioner had again contested the said election but was unsuccessful. Since the petitioner had lost the subsequent election, the challenge raised by her to the order passed by the trial Court had now been rendered infructuous.

On these grounds, it was urged that there was no case made out to interfere with the impugned adjudication.

8. We have heard the learned counsel for the parties at length and with their assistance we have also perused the documentary material on record. Before considering the challenge raised by the petitioner, it would be necessary to first deal with the submission of the first respondent that by virtue of the subsequent election to fill in the vacancy caused by the disqualification of the petitioner, her challenge as raised had been rendered infructuous. In this regard, it is necessary to note that after the present proceedings were filed, a bye election was notified and the polling was scheduled on 07.07.2025. This Court on 25.06.2025 directed that though the bye election could be held, the result thereof would be subject to outcome of the present proceedings. It is thus clear from the aforesaid that the holding of the subsequent election for filling in the vacancy caused by the unseating of the petitioner was made subject to outcome of these proceedings. It therefore cannot be gainsaid that with the conduct of the bye elections, the challenge raised by the petitioner to the order passed by the trial Court had become infructuous. Notwithstanding the conduct of the bye elections, the present challenge would be required to be adjudicated on merits since the rights of the petitioner stand protected by virtue of the interim order dated 25.06.2025. The said contention raised by the first respondent therefore cannot be accepted.

9. Coming to the challenge raised by the petitioner, it is to be noted from the pleadings of the first respondent in the election petition that the petitioner had failed to disclose the fact that on 07.08.2018 she had been convicted under Section 138 of the Act of 1881. This material fact was required to disclosed by her in the affidavit mandated to be filed under Rule 24-A of the Rules of 1994 along with her nomination form. To appreciate this contention, it would be first necessary to refer to the relevant statutory provisions.

Section 22 (1) (d) of the Act of 1961, insofar as it is material fact for the present purpose reads as under:

“22. Grounds for declaring election or nomination to be void- (1) Subject to the provisions of sub-section (2), if the Judge is of the opinion – …………

(d) that the result of the election, or nomination in so far as it concerns a returned candidate has been materially affected –

(i) by the improper acceptance of any nomination; or

(ii) by the improper acceptance or refusal of any vote or reception of any vote which is void; or

(iii) by the non-compliance with the provisions of this Act or of any rules or orders-made there under save the rules framed under Section 14 in so far as they relate to preparation and revision of list of voters; he shall declare the election or nomination of the returned candidate to be void.”

The aforesaid statutory provisions indicate that the election of returned candidate can be declared to be void on account of improper acceptance of his/her nomination form or on account of non-compliance with the provisions of the Act of 1961 or the Rules of 1994 or orders made thereunder.

10. Rule 24-A of the Rules of 1994 requires each candidate to furnish information with regard to declaration of criminal antecedents, assets, liabilities and educational qualifications. The said provision insofar as it is relevant for the present purpose reads as under:

“24-A. (1) Each candidate shall furnish the information relating to -Declaration of criminal antecedent, assets, liabilities and educational qualification-

(i) any pending criminal case in which he is charged and any disposed criminal case in which he has been convicted;”

Rule 24-A (2), (4) and (5) of the Rules of 1994 being relevant are reproduced hereunder:

“(2) The nomination paper shall be rejected, if the affidavit is not enclosed.”

“(4) The Returning Officer shall, as soon as may be after furnishing of the information to him under sub-rule (1), display the aforesaid information by affixing a copy of the affidavit, at a conspicuous place at his office for the information of electors of the concerned ward for which the nomination paper is filed and, shall on demand from any other candidate/elector of the ward, make available the information received of the candidate and, shall also publicize the information received through the media.”

“(5) If any candidate or elector files an affidavit against the information contained in the affidavit filed by a candidate under sub-rule (1), it shall also be displayed in the manner prescribed in sub-rule (4).”

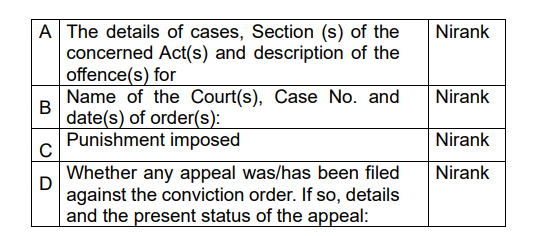

11. As required by Rule 24-A(5) of the Rules of 1994, the petitioner filed her affidavit in the prescribed format. The relevant portion of the said affidavit dated 09.09.2022 reads as under:

AFFIDAVIT

As per Rule 24-A(1)(5)(Amended) of the M.P. Nagarpalika Nirvachan Niyam, 1994

For election to Parshad Ward No.5 from Nagar Parishad, Bhikangaon

(6) I have been/have not been convicted of an offence(s) [other than any offence(s) referred to in sub-section (1) or sub-section (2), or cover in sub-section(3), of section 8 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (43 of 1951)] and sentenced to imprisonment for one year or more.

If the deponent is convicted and punished as aforesaid, he shall furnish the following information: In the following cases, I have been convicted and sentenced to imprisonment by a court of law:

VERIFICATION

I, the deponent, above named, do hereby verify and declare that the contents of this affidavit are true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief and no part of it is false and nothing material has been concealed there from. I further declare that:

(a) There is no case of conviction or pending case against me other than those mentioned in items 5 and 6 of part A and B above;

(b) I, my spouse, or my dependents do not have any asset or liability, other than those mentioned in items 7 and 8 of Part A and items 8, 9 and 10 of Part B above.

Verified at this day of 09/09/2022

DEPONENT

(emphasis supplied by us)

12. Undisputably, the petitioner was convicted on 07.08.2018 under Section 138 of the Act of 1881. The conviction was in force when the petitioner submitted her nomination form on 09.09.2022. In the affidavit filed under Rule 24-A of the Rules of 1994, the petitioner failed to disclose her conviction as stated above. To that extent, the plea raised by the first respondent and accepted by both Courts that there was a failure on the part of the petitioner in not disclosing her conviction in the affidavit filed under Rule 24-A of the Rules of 1994 which in turn resulted in non-compliance with the provisions of the Act of 1961 or the Rules of 1994 is correct.

13. On consideration of the statutory provisions as well as the documentary material on record it becomes clear that under Rule 24-A (1) of the Rules of 1994, every candidate contesting elections is required to furnish information which includes declaration of criminal antecedents, etc. The information required to be furnished is with regard to any pending criminal case in which the candidate is charged or any criminal case that has been disposed of and has resulted in his conviction. Failure to furnish such affidavit can result in rejection of the nomination paper. The Returning Officer is required to display the nomination furnished by each candidate by affixing a copy of the affidavit at a conspicuous place at his office so as to provide information to the electors from the concerned ward. He is also required to publicise the information received through the media. Similarly, contents of the affidavit required to be filed under Rule 24-A (1) are also required to be displayed in the aforesaid manner. The object behind disclosing such information is to enable the voters to get knowledge about the criminal antecedents, assets, liabilities and educational qualifications of the candidates contesting the elections. That such information is required to be furnished in furtherance of the right to information available to the electorate under Article 19 (1) (a) of the Constitution of India is now wellsettled.

14. In this context, it would be necessary to refer to the three Judge Bench decision in Union of India vs. Association for Democratic Reforms5. While considering the question whether a voter had a right to get relevant information including that with regard to involvement in an offence, this Court while recognising such right to get information in the context of Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India held as under:

“In our view, democracy cannot survive without free and fair election, without free and fairly informed voters. Votes cast by uninformed voters in favour of X or Y candidate would be meaningless. As stated in the aforesaid passage, onesided information, disinformation, misinformation and noninformation all equally create an uninformed citizenry which makes democracy a farce. Therefore, casting of a vote by misinformed and non-informed voter or a voter having onesided information only is bound to affect the democracy seriously. Freedom of speech and expression includes right to impart and receive information which includes freedom to hold opinions. Entertainment is implied in freedom of ‘speech and expression’ and there is no reason to hold that freedom of speech and expression would not cover right to get material information with regard to a candidate who is contesting election for a post which is of utmost importance in the democracy.”

It thereafter concluded as under:

“Under our Constitution, Article 19(1)(a) provides for freedom of speech and expression. Voters’ speech or expression in case of election would include casting of votes, that is to say, voter speaks out or expresses by casting vote. For this purpose, information about the candidate to be selected is must. Voter’s (little man citizen’s) right to know antecedents including criminal past of his candidate contesting election for MP or MLA is much more fundamental and basic for survival of democracy. The little man may think over before making his choice of electing law breakers as law makers.”

15. It is an admitted position that, the petitioner failed to disclose her conviction for the offence punishable under Section 138 of the Act of 1881 and that she had been sentenced to imprisonment for a period of one year. It is also not disputed that on 09.09.2022 when the petitioner submitted her affidavit as required by Rule 24-A (1) of the Rules of 1994, her conviction was in force. The petitioner was therefore obligated to furnish information about her conviction and consequently being sentenced to imprisonment for a period of one year. She however failed to do so. Pertinently, Rule 24-A(1) requires a declaration to be made of an order or conviction, irrespective of the quantum of sentence imposed. In other words, the material information to be furnished is the fact of any conviction suffered by a candidate. It is therefore clear that by failing to disclose her previous conviction, the petitioner furnished false and incorrect information as regards her criminal antecedents. As a result the verification of her affidavit was false and incorrect despite the fact that the petitioner had full knowledge of her conviction which she had subjected to further challenge. As a consequence, the ground under Section 22 (1) (d) (iii) of the Act of 1961 became available for declaring her election to be void. Further, as a result of such false information being furnished by the petitioner in her affidavit filed under Rule 24-A (1) of the Rules of 1994, her nomination paper was improperly accepted.

These factual aspects have been considered by the trial Court and thereafter affirmed by the High Court in exercise of its revisional jurisdiction. This factual position was not contested by the learned Senior Advocate for the petitioner. It is thus clear that by failing to disclose her conviction and consequent sentence of imprisonment for a period of one year, a ground for declaring her election as Councillor became available to the first respondent.

16. The learned Senior Advocate for the petitioner tried to extricate the case of the petitioner from such position by urging that the conviction of the petitioner was not for an offence involving moral turpitude. It was a conviction under Section 138 of the Act of 1881 and thus it could not be said that there was any serious or heinous crime committed by the petitioner. For her conviction in such an offence, the petitioner was not liable to be visited by an order of disqualification under the Act of 1961. To substantiate this contention he sought to derive support from the decisions of this Court in Ravi Namboothiri and Karikho Kri (supra). Having considered both these decisions, we find that the same are clearly distinguishable in view of the statutory provisions involved therein as well as the relevant factual aspects. In Ravi Namboothiri (supra), the appellant therein was finally convicted for the offence punishable under Section 38 read with Section 52 of the Kerala Police Act, 1961 and was sentenced to a fine of Rs. 200/-.

The said appellant however while filing his nomination for the elections to the Panchayat failed to disclose the fact of his conviction under Section 38 read with Section 52 of the Kerala Police Act, 1961. On this count his election to the Panchayat was set aside as he had suppressed information with regard to his past conviction. The appellant challenged his disqualification before this Court. It was found that what was required to be disclosed under Section 52(1A) of the Kerala Panchayat Raj Act, 1994 were the details with regard to criminal cases in which the candidate was involved at the time of submission of his nomination. Reference was made to the previous of Section 102 (1)(ca) of the Kerala Panchayat Raj Act, 1994 which made furnishing of details by an elected candidate under Section 52 (1A) a ground for declaring an election to be void if such details furnished were fake. It was held by this Court that the word “involvement’’ in a criminal case at the time of filing of the nomination in Section 52 (1A) would only mean cases where a criminal complaint was pending investigation/trial, cases where the conviction and/or sentence was current at the time of filing of the nomination and cases where the conviction was the subject matter of any appeal or revision pending at the time of nomination. It was found that besides Rule 6, Form No. 2-A required details even of cases where the candidate was convicted earlier. Since the said appellant had failed to disclose details of his earlier conviction in Form No.2-A, his election was liable to be declared as void under Section 102 (1)(ca). This Court however found that under provisions of Section 38 and 52 of the Kerala Police Act, 1961, the conviction of the said appellant was for disobedience of the directions issued by a police officer. By observing that such offence could not be treated to be a substantive offence, it was observed that protest was a tool in hands of the society and therefore failure on the part of said petitioner to disclose his conviction for the offence consequent upon holding a ‘dharna’ in front of the Panchayat Office could not be taken as a ground for declaring an election to be void. It further observed that the Kerala Police Act, 1961 was a successor legislation of certain police enactments of the colonial era, whose object was to scuttle the democratic aspirations of the indigenous population. Accordingly, this Court held that the High Court was not correct in declaring the election of the said petitioner to be void on the ground that he had failed to disclose to in Form No.2-A of his conviction which amounted to undue influence on the free exercise of the electoral right.

17. We may note that in the aforesaid decision, the requirement was to furnish information with regard to involvement in a criminal case as required by Section 52(1A) of the Kerala Panchayat Raj Act, 1994. Further the said appellant on his conviction was merely sentenced to fine of Rs.200/- for the offence under Section 38 read with Section 52 of the Kerala Police Act, 1961. There was no sentence of imprisonment. In the present case, the petitioner after her conviction was sentenced to an imprisonment for a period of one year. The affidavit required to be filed under Rule 24-A (1) of the Rules of 1994 specifically requires furnishing of details as regards any sentence of imprisonment for a period of one year or more. The statutory requirement in the present case is thus distinct from the requirements in Ravi Namboothiri (supra) which makes the said decision distinguishable.

18. In Karikho Kri (supra), the successful candidate in the assembly elections was found to have not disclosed in his affidavit details with regard to ownership of vehicles, failure to submit no dues certificate with regard to electricity charges and municipal dues. His election was declared to be void under Section 100 (1)(d)(i) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. While considering the challenge to the judgment of the High Court, this Court found that the vehicles in question had either been gifted or sold by the appellant prior to filing of his nomination and hence the said vehicles could not be considered to be owned by his family members. It was further found that the said appellant had disclosed the value of his assets which included the value of the vehicles in question. It was then found that what was not disclosed by the appellant was not of a substantial nature so as to impact his candidature or the result of the election. In fact, a finding was recorded that there were no actual outstanding dues payable by the appellant and hence there was no defect whatsoever so as to render the acceptance of his nomination form to be improper. Additionally, it was found that though the election of the appellant had been invalidated under Section 100(1)(d)(iv) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, it had not been shown as to how the result of the election had been materially affected by the acceptance of his nomination form. On these counts, the judgment of the High Court was set aside and the election of the said appellant was found to be valid.

The aforesaid facts are sufficient to distinguish the said decision in the wake of the undisputed facts of the present case. The petitioner herein having been convicted and sentenced to imprisonment for a period of one year which fact was not disclosed in the affidavit filed along with the nomination form is sufficient to hold that the ratio of the aforesaid decision cannot be applied to the present case.

19. It is now necessary to deal with the contention raised on behalf of the petitioner that notwithstanding her conviction, the same was not for committing a serious offence or one touching upon moral turpitude. The conviction being under Section 138 of the Act of 1881, the petitioner was not liable to be unseated for her conviction for a minor offence.

We are unable to accept this contention which seeks to dilute the fact of non-disclosure of the petitioner’s conviction in the nomination form. Rule 24A-(1) requires a candidate to disclose any order of conviction suffered by him by filing an affidavit along with the relevant information before the Returning Officer. The format of the affidavit prescribed under the Rules of 1994 requires a disclosure as regards conviction and sentence of imprisonment for a duration of one year and more. The validity of Rule 24-A(1) of the Rules of 1994 has not been subjected to any challenge. It would therefore have to be treated as valid. Its compliance has been made mandatory as failure to furnish such information along with an affidavit as prescribed visits a candidate with the consequence of non-compliance of the provisions of the Rules of 1994. This in turn is a ground to challenge the election of the returned candidate. In absence of any provision in the Rules of 1994 that would enable the Court to condone such non-compliance or exempt its compliance on the ground that the conviction was for a non-serious offence or one not involving moral turpitude, adopting such course as urged would do violence to the Act of 1961 and the Rules of 1994.

20. At this stage, we may refer to the decision of this Court in Krishnamoorthy (supra) wherein this Court considered the effect of non-disclosure of criminal cases in respect of serious offences including those involving moral turpitude. After noting that the right to contest an election was neither a fundamental right nor a common law right, it was observed as under:

“The controversy which has emanated in this case is whether non-furnishing of the information while filing an affidavit pertaining to criminal cases, especially cases involving heinous or serious crimes or relating to corruption or moral turpitude would tantamount to corrupt practice, regard being had to the concept of undue influence”.

It was thereafter concluded in paragraph 86 as under:

“In view of the above, we would like to sum up our conclusions:

(a) Disclosure of criminal antecedents of a candidate, especially, pertaining to heinous or serious offence or offences relating to corruption or moral turpitude at the time of filing of nomination paper as mandated by law is a categorical imperative.

(b) When there is non-disclosure of the offences pertaining to the areas mentioned in the preceding clause, it creates an impediment in the free exercise of electoral right.

(c) Concealment or suppression of this nature deprives the voters to make an informed and advised choice as a consequence of which it would come within the compartment of direct or indirect interference or attempt to interfere with the free exercise of the right to vote by the electorate, on the part of the candidate.

(d) As the candidate has the special knowledge of the pending cases where cognizance has been taken or charges have been framed and there is a nondisclosure on his part, it would amount to undue influence and, therefore, the election is to be declared null and void by the Election Tribunal under Section 100(1)(b) of the 1951 Act.

(e) The question whether it materially affects the election or not will not arise in a case of this nature.”

This Court was concerned with the suppression of various cases of embezzlement by the concerned candidate in his nomination form. The reference to heinous or serious offences or offences relating to corruption or moral turpitude would have to be seen in that factual backdrop. This Court was not dealing with an offence that was not heinous or not involving moral turpitude. It is therefore not the ratio of Krishnamoorthy (supra) that disclosure only of serious and heinous offences is mandated and that failure to disclose conviction for a minor or non-serious offence could be condoned, as a principle. We may however clarify that ultimately it is a matter of exercise of judicial discretion in the given facts of the case, as was exercised in Ravi Namboothiri (supra), as to whether such nondisclosure is fatal or not. Hence, the decision in Krishnamoorthy (supra) cannot be the basis to hold that non-disclosure of conviction in case of a minor offence was always intended to be condoned and not viewed seriously.

21. The plea raised by the petitioner that her election could not be set aside in the absence of it being proved that the result of the election had been materially affected on account of the improper acceptance of her nomination form need not detain us. Once it is found that there has been non-disclosure of a previous conviction by a candidate, it creates an impediment in the free exercise of electoral right by a voter. A voter is thus deprived of making an informed and advised choice. It would be a case of suppression/non-disclosure by such candidate, which renders the election void.

22. In this regard, we may refer to the decision in Kisan Shankar Kathore vs. Arun Dattatray Sawant & Others6. Therein the election of the returned candidate to the Legislative Assembly was challenged by a voter from the constituency on the ground that the nomination form of the returned candidate had been improperly accepted by the Returning Officer and that the election was void due to non-compliance of the provisions of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. There were in all five candidates in the fray. In the election petition, the High Court held that the returned candidate failed to make material disclosures in the affidavit filed along with the nomination form and hence the nomination form was improperly accepted by the Returning Officer. It further held that the result of the election was materially affected due to non-disclosure of relevant information. Accordingly, the election of the returned candidate was set aside. While considering the challenge to the said judgment, this Court noted that the aspect of non-disclosure of material information was an admitted fact. Referring to the decisions in Association for Democratic Reforms (supra) and People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) Vs. Union of India and another7, it was held that if the required information as per the guideline the Election Commission was not given, the same would amount to suppression/non-disclosure of relevant information. On the aspect of the result of the election being materially affected due to nondisclosure of such information, it was observed in paragraph 28 as under:-

“Issue No. 8 pertains to the question as to whether the election result was materially affected because of nondisclosure of the aforesaid information. The High Court took note of provisions of Section 100 (1)(d)(i) and (iv) and discussed the same. Thereafter, some judgments cited by the appellant were distinguished and deciding this issue against the appellant, the High Court concluded as under:

“137. In my opinion, it is not necessary to elaborate on this matter beyond a point, except to observe that when it is a case of improper acceptance of nomination on account of invalid affidavit or no affidavit filed therewith, which affidavit is necessarily an integral part of the nomination form; and when that challenge concerns the returned candidate and if upheld, it is not necessary for the Petitioner to further plead or prove that the result of the returned candidate has been materially affected by such improper acceptance.

138. The avowed purpose of filing the affidavit is to make truthful disclosure of all the relevant matters regarding assets (movable and immovable) and liabilities as well as criminal actions (registered, pending or in respect of which cognizance has been taken by the Court of competent jurisdiction or in relation to conviction in respect of specified offences). Those are matters which are fundamental to the accomplishment of free and fair election. It is the fundamental right of the voters to be informed about all matters in relation to such details for electing candidate of their choice. Filing of complete information and to make truthful disclosure in respect of such matters is the duty of the candidate who offers himself or who is nominated for election to represent the voters from that Constituency. As the candidate has to disclose this information on affidavit, the solemnity of affidavit cannot be allowed to be ridiculed by the candidates by offering incomplete information or suppressing material information, resulting in disinformation and misinformation to the voters. The sanctity of disclosure to be made by the candidate flows from the constitutional obligation.”

Affirming the said finding, it was held in paragraph 38 as under:-

“…Once it is found that it was a case of improper acceptance, as there was misinformation or suppression of material information, one can state that question of rejection in such a case was only deferred to a later date. When the Court gives such a finding, which would have resulted in rejection, the effect would be same, namely, such a candidate was not entitled to contest and the election is void…”

23. In Sri Mairembam Prithviraj @ Prithviraj Singh Vs. Shri Pukhrem Sharatchandra Singh ((2016 INSC 1000)), two candidates were in the election fray. The returned candidate failed to submit any documents as regards his educational qualification alongwith the nomination form. The acceptance of his nomination form was accordingly challenged. The High Court held that the declaration made by the returned candidate as regards his educational qualification was false. The said finding was upheld by this Court. On the question as to whether the election of the returned candidate was materially affected due to such improper acceptance of the nomination form, reference was made to the decision in Kisan Shankar Kathore (supra). It was thereafter held in paragraph 23 as under:-

“23. Mere finding that there has been an improper acceptance of the nomination is not sufficient for a declaration that the election is void under Section 100 (1) (d). There has to be further pleading and proof that the result of the election of the returned candidate was materially affected. But, there would be no necessity of any proof in the event of the nomination of a returned candidate being declared as having been improperly accepted, especially in a case where there are only two candidates in the fray. If the returned candidate’s nomination is declared to have been improperly accepted it would mean that he could not have contested the election and that the result of the election of the returned candidate was materially affected need not be proved further. We do not find substance in the submission of Mr. Giri that the judgment in Durai Muthuswami (supra) is not applicable to the facts of this case.”

Though in the aforesaid case there were only two candidates who contested the elections, the principle that failure to disclose relevant information in the affidavit filed along with the nomination form amounted to non-disclosure of material information was accepted. That such wrongful acceptance of the nomination form of the returned candidate would result in the election being materially affected rendering it void was recognised as a consequence.

24. Even otherwise, it is clear from the decision in Krishnamoorthy (supra) that non-furnishing information pertaining to criminal antecedents has the effect of causing undue influence which creates an impediment in the free exercise of electoral right by a voter. When there is such non-disclosure of criminal antecedents, this Court held in paragraph 86(e) that the question whether the election is materially affected or not would not arise in such a case.

It is thus clear that by failing to disclose her conviction under Section 138 of the Act of 1881, the petitioner suppressed material information and thus failed to comply with the mandatory requirements of Rule 24-A(1) of the Rules of 1994. The acceptance of her nomination form has therefore been rightly held to be improper. She being the returned candidate, her election was rendered void. It is thus obvious that on account of such wrongful acceptance of her nomination form, the election was materially affected. This contention of the petitioner also fails.

25. We may now indicate why discretion under Article 136 of the Constitution of India does not deserve to be exercised in the present case. The Constitution Bench in Pritam Singh vs. State ((1950 INSC 9)) while explaining the scope and powers of the Court under Article 136 has held that:

“Generally speaking, this Court will not grant special leave, unless it is shown that exceptional and special circumstances exist, that substantial and grave injustice has been done and that the case in question presents features of sufficient gravity to warrant a review of the decision appealed against.”

Having considered the entire matter, we are not persuaded to hold that the petitioner has made out an exceptional case for this Court to hold that notwithstanding the failure on the part of the petitioner to disclose her conviction leading to the sentence of imprisonment of one year, such lapse should be condoned. The information furnished in her affidavit filed under Rule 24-A(1) of the Rules of 1994 has been found to be incorrect and false. The petitioner rests on her subsequent acquittal in appeal, which event occurred after her election. She did not step into the witness box to explain her inadvertence, which is now sought to be put forward. The plain reading of Rule 24-A(1) and its requirement does not admit of any doubt whatsoever. Moreover, both the Courts have concurrently found that the petitioner failed to disclose her conviction without any justifiable reason. In these facts therefore, no special or exceptional case has been made out by the petitioner for this Court to exercise jurisdiction under Article 136 of the Constitution of India. In the passing, we may observe that the petitioner had contested the bye election that had occasioned by her removal and she lost the same.

26. For all the above reasons, the Special Leave Petition stands dismissed.