Analysis

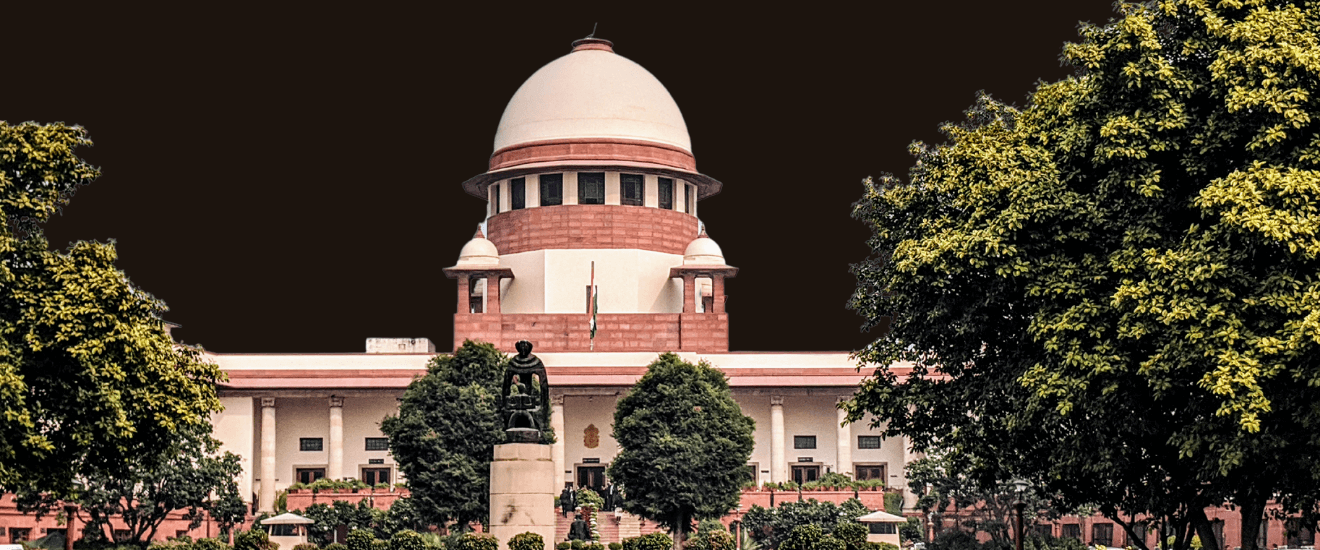

Judicial Transfers: Sankalchand Redux?

Judicial Transfers without consent of judges demonstrates tussle between the executive and judiciary.

In 1976, the President transferred Sankalchand H. Sheth J from the Gujarat High Court to the High Court of Andhra Pradesh, without his consent. Justice Sheth complied with the presidential order, and assumed his new office. Yet he challenged the order as being based on a faulty interpretation of Article 222(1) of the Constitution. He claimed that his consent was required and the executive did not hold ‘effective consultation’ with the Chief Justice of India. Unfortunately for him, the Supreme Court ruled that the President had the power to transfer judges with neither their consent nor the ‘concurrence’ of the Chief Justice of India (CJI).

For the last 4 decades Sankalchand was bad law as the Supreme Court collegium wrested control of judicial appointments and transfers from the executive branch. The Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) which governs high court judicial appointments and transfers gives primacy to the Supreme Court Collegium and CJI who must act in the public interest and promote the ‘better administration of justice throughout the country’.

Recent developments concerning Kureshi J’s appointment test the law in this field. For four months, the Union ignored the Collegium’s May 10th recommendation to elevate Kureshi J to Chief Justice of the Madhya Pradesh High Court. The GHCAA filed a PIL on July 3rd praying for Kureshi J’s immediate appointment, shifting the issue from the administrative to the judicial side. The Union Law Ministry finally responded to the CJI but insisted that Kureshi J be transferred to a different High Court. It’s unclear if the CJI will resolve this impasse on the administrative or judicial side. In any event, the ghost of Sankalchand lingers over High Court judicial transfers in India.

Sincerely,

SC Observer Desk

(This post is extracted from our weekly newsletter, the Desk Brief. Subscribe to receive these in your inbox.)