Analysis

Unpacking Original Jurisdiction of SC #2: Legal Precedents

Several cases have been filed under Article 131 particularly in terms of constitutional violations by Central legislations.

In a suit filed in the Supreme Court in January 2020, the state of Kerala challenged the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019 (CAA). This suit is unique because in other instances, petitioners, as ordinary citizens, have challenged the CAA under Article 32 of the Constitution, Kerala has instead relied on Article 131, invoking the ‘original jurisdiction’ of the Supreme Court to adjudicate on disputes between the State and the Centre.

In part 1 we explored the constitutional history and scope of Article 131. In part 2, we will examine the legal precedents around Article 131 to shed some light on how the Court has previously dealt with constitutional challenges to Central legislation by States.

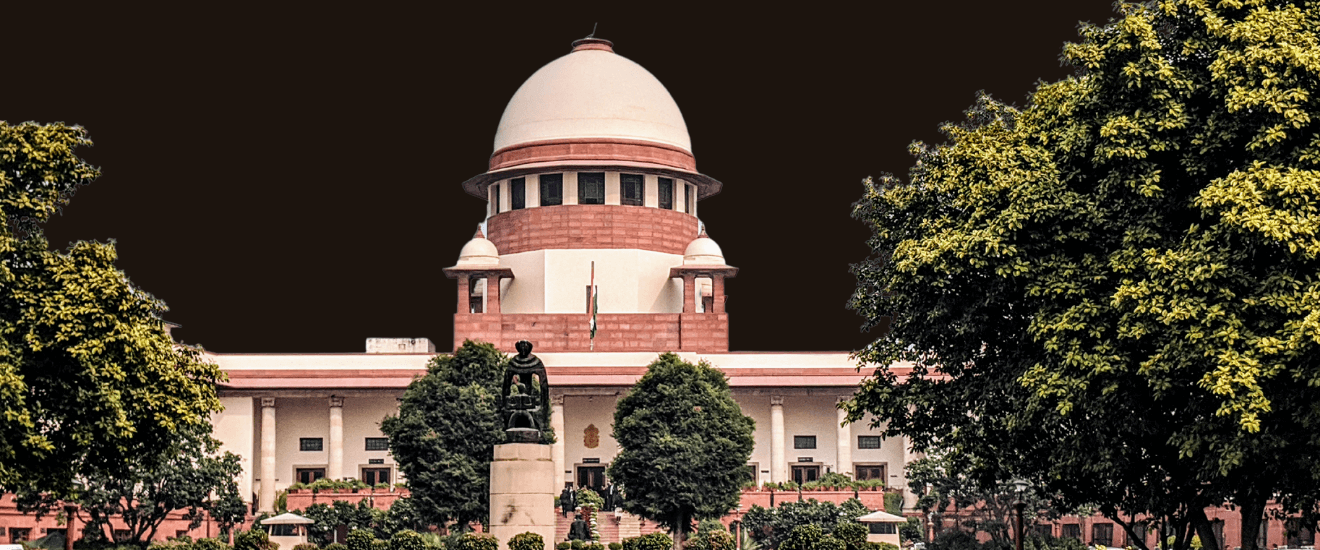

Image Credits: Kerala Chief Minister P Vijayan

Precedent on the use of Article 131

Article 131 has been invoked in several cases to adjudicate disputes between the Centre and a State. In the case of State of Rajasthan v Union of India (1973), Chandrachud J held that “mere wrangles between governments” had no place under Article 131. In State of Karnataka v Union of India (1977) Bhagwati J interpreted the scope of Article 131 rather broadly, holding that it was sufficient if the suit concerned a question on which the “existence or extent” of a legal right depends, regardless of whether or not this right was violated. The Court, in this case, concluded that Article 131 could be invoked “whenever a State and other States or the Union differ on a question of interpretation of the Constitution so that a decision of it will affect the scope or exercise of governmental powers which are attributes of a State.”

However, this case was quite different from the one filed by the State of Kerala. Where the State of Karnataka case had to do with a question of authority, the present case asks for an examination of constitutionality. It is not entirely clear whether Article 131 empowers the Supreme Court to perform such an inquiry on legislation passed by the Centre or make a declaration of unconstitutionality at the behest of a State.

Most recently in 2011, in State of Madhya Pradesh v Union of India, the two-member bench of Justices Sathasivam and Chauhan held that an original suit filed under Article 131 was not an ‘appropriate forum’ to challenge the constitutionality of legislation passed by the Union Government. The Court held that the correct route for such a challenge was either Article 32 or Article 226 of the Constitution.

Three years later in State of Jharkhand v State of Bihar, the defendant relied on the 2011 judgment to argue that an original suit under Article 131 as to the constitutionality of a clause of the Bihar Reorganisation Act, 2000 was not maintainable. In response, the two-member bench of Chelameswar and Bobde JJ rejected the defendant State’s reliance on the ruling in State of Madhya Pradesh v Union of India, saying that it ‘[regretted its] inability to agree with the conclusion’ in that case. This rejection was based mainly on their determination that the language of Article 131 made it amply clear that the Court’s exclusive original jurisdiction extended to any disputes between the Government of India and any State(s), whether of law or fact—as long as it concerned a legal right as defined by Justice Bhagwati in State of Karnataka v Union of India. However, since both cases were heard by two-member bench, the latter was unable to overrule the decision of the former.

Thus, the question as to whether Article 131 can be used to examine the constitutionality of legislation was referred to a larger bench composed of three justices, headed by N.V. Ramana J, where it is still pending.

What next?

The State of Kerala, in its original suit, relied upon two points to support the maintainability of its claim. First, it argued that Article 256 of the Constitution compels the State of Kerala to implement the CAA, which causes a dispute between the State and the Union involving questions of both law and fact, concerning the legal rights of those that live in the State. Thus, it clears the test of subject matter laid out by Chandrachud and Bhagwati JJ in 1973 and 1977. The State of Kerala made this argument in anticipation of the assertion by BJP leader Kummanam Rajasekharan that the suit concerns a question that is political rather than legal. Second, it argued that as per the judgement of the bench in State of Jharkhand v State of Bihar, the question of constitutionality was one that may be considered by the Court under Article 131.

Thus, while the first question of subject matter appears to be resolved by the suit itself, the second remains uncertain. The decision of Justice Ramana’s bench on this question will have a significant bearing on the suit filed by the State of Kerala. If the bench finds that exclusive original jurisdiction under Article 131 cannot be used to challenge the constitutionality of legislation passed by the centre, it is highly unlikely that the Kerala government’s suit can be maintained. However, if it does find that constitutionality is a question that Article 131 allows, following the conclusion of the Court in State of Jharkhand v State of Bihar, the Kerala suit is likely to be maintained and considered by the Court. This will also set a precedent for other original suits such as that filed by the State of Chhattisgarh challenging the National Investigative Agency Act, 2008.

(Manini Menon is a first-year student of BA Jurisprudence (Senior Status) at the University of Oxford. She is currently interning with us.)

Resources