Analysis

Seventy-Five years on: A Constitution still in negotiation

V. Krishna Ananth’s book argues that authoritative tools were a foundational compromise in the Constitution

Constitution of India: 75 Years of the World’s Largest Democracy, by V. Krishna Ananth, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (P) Ltd., New Delhi, 2025, Pages: xxix +1011, ₹1895, (discounted: ₹1325)

Constitution of India: 75 Years of the World’s Largest Democracy, by historian V. Krishna Ananth is not a commemorative reflection, but a rigorously argued political history of India’s constitutional experience. Rather than treating the Constitution as a fixed legal code interpreted solely by the judiciary, Ananth engages with it as a living document shaped by political contestation. Across over a thousand pages, Ananth offers a reference work that also functions as a political argument. He situates constitutional development within the interplay of state power, popular movements and institutional negotiation.

Ananth’s distinctive contribution lies in reading constitutional change through the lens of political struggle. He refuses to isolate judicial interpretation from legislative and executive action, showing how the Constitution has been used to facilitate both progressive reform and executive consolidation. Drawing on his earlier work on the right to property, he now expands the canvas to encompass a wider range of constitutional conflicts—liberty, land reform, federalism, preventive detention and emergency powers. The result is a constitutional history that foregrounds Parliament and elected governments, without romanticising them.

The book is chronologically structured but thematically layered. It traces founding debates, early amendments, land reform battles, the centralising turn of the 1960s and 1970s, the Emergency and its afterlives and the contemporary period of executive assertiveness and majoritarian politics. Ananth’s prose is direct and its dense documentation is aimed at students, lawyers, journalists and researchers. It is not an introductory text, but a deep dive for those seeking to understand how political pressures have reshaped constitutional doctrine and institutional behaviour.

Preventive detention

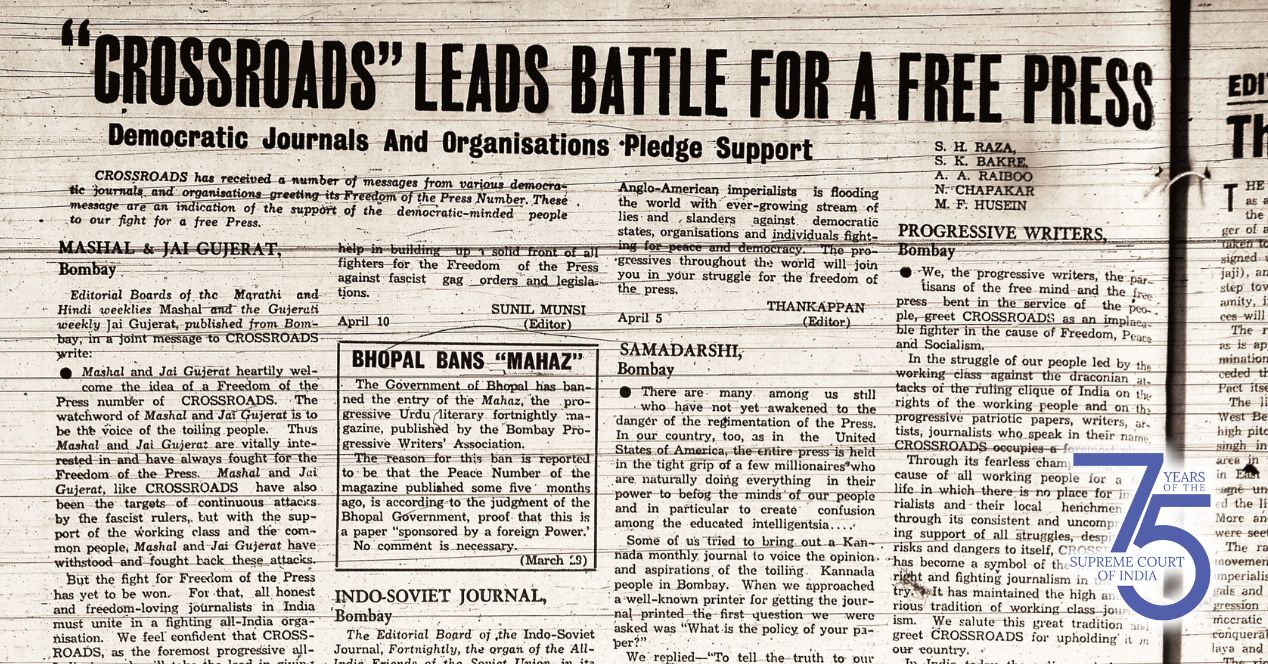

Ananth argues that the constitutional endorsement of preventive detention, through Article 22, reflects a “fear of freedom” embedded in the founding framework. This was not merely a postcolonial anomaly, but a structural feature born out of colonial continuities, partition anxieties and a political class wary of mass politics. From this perspective, contemporary uses of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 and the National Security Act, 1980 are not aberrations but logical extensions of constitutional choices made early on. This reframing challenges the view that authoritarian turns began only in the recent past.

The Supreme Court

Ananth offers an unsentimental treatment to the Supreme Court. He challenges the heroic narrative often attached to the Court’s civil liberties jurisprudence, arguing that its record is uneven. From A.K. Gopalan v State of Madras (1950) to A.D.M Jabalpur v S.S. Shukla (1976), he presents the judiciary as frequently deferential to executive power, especially in moments of political crisis. While acknowledging recent jurisprudence that has expanded civil rights, he situates it within broader trends where judicial affirmation of liberty coexists with the Court’s acceptance of growing administrative authority. The Court is a central actor in his story, but never the sole or dominant one.

The chapters on property and social revolution are among the book’s strongest. Here, Ananth examines the constitutional and legislative attempts to restructure agrarian relations and the judicial resistance these efforts encountered. He shows how the First, Fourth, Seventeenth and Twenty-fifth Amendments were not simply attempts to curtail judicial power but were aimed at aligning the Constitution with developmental priorities. In this respect, Ananth echoes Granville Austin’s “cornerstone” thesis but with greater scepticism about elite motives. Even when state action claimed socialist objectives, it often protected institutional authority as much as distributive justice.

The Emergency

The Emergency is treated as a culmination of processes that were already in motion and not a historical rupture. The legal and constitutional tools that enabled its imposition—detention powers, constitutional amendments, judicial acquiescence—were embedded in the system. This historical continuity has implications for how we understand current trends of executive dominance, tribunalisation and surveillance. For Ananth, the problem is not that authoritarian tools have recently emerged, but that they were built into the constitutional architecture early on.

Sharp insights

Nevertheless, there are areas where the book leaves more to be desired. It pays limited attention to the Court’s recent jurisprudence on representation, identity and institutional functioning. Developments in 2024-25—on electoral bonds, reservation or institutional autonomy—are understandably not covered, but prior debates on how the Court manages benches, rosters and interim orders could have received more attention. The absence of a consolidated analysis of how the judiciary structures its own institutional authority is a notable omission in an otherwise comprehensive volume.

Despite these gaps, Ananth’s work marks a significant contribution to constitutional historiography. It aligns with recent critical volumes that reassess the judiciary’s role, such as Senior Advocate S. Muralidhar’s edited collection, In(complete) Justice?: The Supreme Court at 75. Ananth’s strength lies in tracing institutional continuity and placing constitutional crises within a longer trajectory of contestation. His perspective insists that the challenges faced today are not departures from constitutionalism but are often its product.

This book is unlikely to be purchased casually. It is best suited for institutional libraries, law departments and scholars of Indian constitutionalism. That is a pity, for buried in its pages are sharp, quotable insights: that the Court’s civil liberties record is “uneven rather than heroic.” That Parliament’s amendment drives were often attempts to realign the Constitution with political demands, and that preventive detention was never a deviation but a foundational compromise.