Analysis

Divyang, ‘Sitaare Zameen Par’ and the constitutional lives of the disabled

The Censor’s directive to include a message from the PM reflects the State’s tendency to contend with the disabled on its own, flawed terms

Recently, the Central Board for Film Certification directed the makers of Sitaare Zameen Par to add a message by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the film’s opening credits. The protagonist of the film, which is a remake of the Spanish-language Campeones, is a suspended basketball coach who is compelled to train a team of players with disabilities as a form of community service.

Here is the text of the PM’s message that had to be shown:

“In 2047, when we celebrate the 100th anniversary of Independence, our divyang friends will be seen as an inspiration to the whole world. Today we have to be determined for this goal. Let us all build a society where no dream or goal is impossible—only then we will be able to build a truly inclusive and developed India.”

This development, and the occasion of India’s 79th Independence Day, provide an entry point for us to discuss the term ‘Divyang’ and the constitutional lives of the disabled. While scholars in the fields of law and cinema have explored narratives around India’s secular imagination to make sense of lives in a democracy, disabled lives have remained marginal in the discourse.

This fringe treatment begins from the Constitution, which has a deep normative deficiency towards disabled lives. In this brief article, we contend with how categorisation, stereotyping and covert labelling stigmatise disability.

‘Harijan’, ‘Divyang’ and contested fraternity

The word ‘Divyang’, which translates to ‘the one with the divine body’, has been problematised by critical disability scholars since its inception. They have found it ‘diabolical’ and hermeneutically marginalising. It has also been noted that the term has an uncanny similarity with ‘Harijan’, which was coined by Mohandas Gandhi.

Gopal Guru argues that the Gandhian enunciation of ‘Harijan’ was complex and part of his larger search for universal truth in a society torn apart by untouchability—a search that had distinct criteria for the ‘untouchables’, who were closer to universal truth and fellowship, and savarnas, who lacked access to truth owing to their ‘repulsive social attitude towards untouchables’ from which they must ‘detoxify themselves’ through a constant ‘moral editing’.

In Guru’s view, this complexity was lost in the work of later scholars and activists who approach ‘Harijan’ as (a) a passive term that connotes sympathy and ‘theological parentage’ and the evasion of moral responsibility for the practice of untouchability by savarnas; or (b) as stigmatising and violent. It is this euphemistic use of ‘Harijan’, devoid of political charge, that has ruled the discourse on Gandhian approaches to untouchability from various standpoints, leading to its fading out from intellectual engagements.

In a manner of speaking, the coinage of ‘Divyang’ in 2015 made way for the second coming of ‘Harijan’ in our political discourse. Since ‘Divyang’ was used for a minority often described in judicial decisions as ‘discrete and insular’ and outside the realm of the political, the usage did not attract critical scholarly attention even within the disability rights movement.

Other radical movements, of course, have approached the category of ‘disability’ as an apolitical one—witness the late entry of disability as a ground for the release of the late Dr. G.N. Saibaba from custody. So ‘Divyang’ became a default setting, tied to governmental and judicial moves, escaping scrutiny that might have exposed its exclusionary nature.

There is, however, a difference in political orientation between Gandhi’s ‘Harijan’ and Modi’s ‘Divyang’. It is seen in how the usage of the words would stack up against the meaning of ‘fraternity’ within India’s constitutional imagination. Dhananjay Rai points out that Gandhi’s constructive programme geared towards Poorna Swaraj outlined four components: Hindu-Muslim unity, removal of untouchability, prohibition and the charkha. Despite having an in-built hermeneutical injustice, the term ‘Harijan’ is not based on an idea of ‘political’ that makes a distinction between friend and enemy. An inclusive fraternity remains pivotal in the Gandhian outlook despite the limitations of his paternalistic lens and vocabulary.

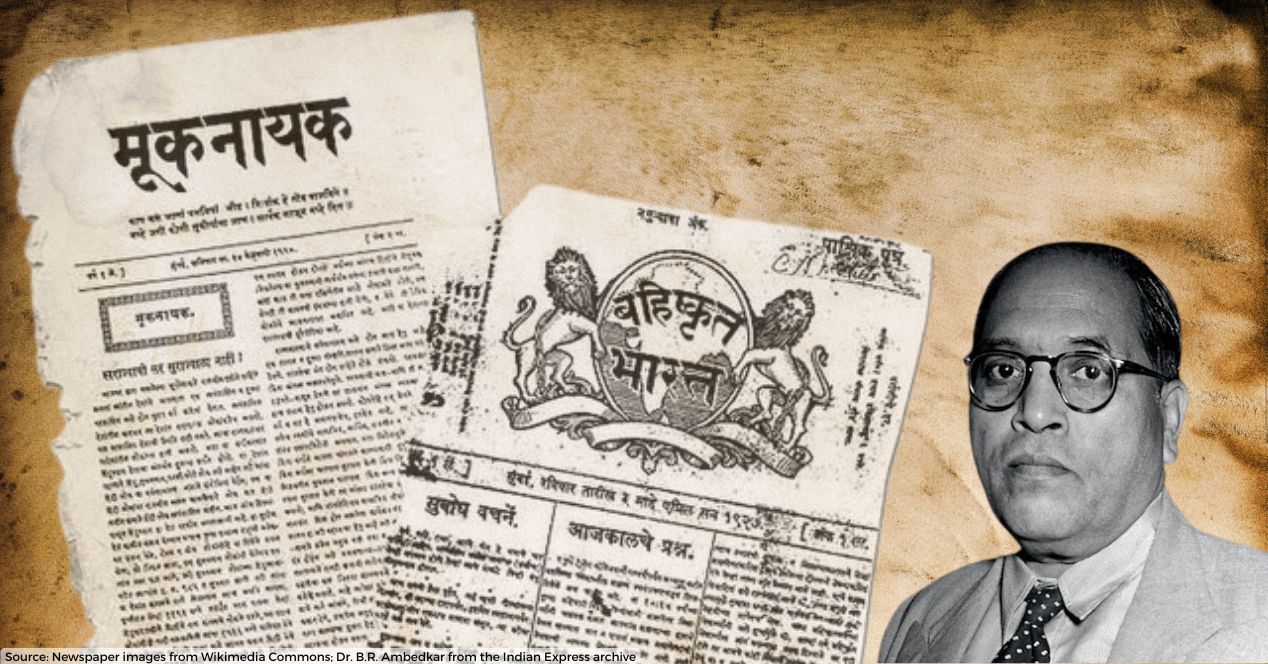

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was categorical about the lack of fraternity in Indian society when he said in anguish: ‘Gandhiji, I have no homeland’. In his final speech in the Constituent Assembly, he asserted that ‘equality and liberty will be no deeper than coats of paint’ without ‘fraternity’.

For him, the annihilation of caste would open pathways to fraternity. This movement had begun to imagine the complex ways in which we might achieve an egalitarian republican life, mindful of dense diversities, pluralisms and intersections of the social with sororal, non-binary, gender-fluid fraternity. In this conception of the world, justice and maithri emerge as core values.

Suffice to say that there is a deep and illuminating complexity to the Gandhian and Ambedkarite debates on fraternity. This is reflected in postcolonial writing on the subject as well. However, this extensive work does not touch on disability as a measure of diversity or plural embodiments; nor is disability theorised as a core aspect of justice that intersects in various ways at various levels with other grounds of disentitlement in defeating justice claims.

It is against this background that we argue that while ‘Harijan’ and ‘Divyang’ may both, at first glance, have their genesis in Hindu epistemic privilege, the use of ‘Divyang’ is more problematic, and deeply so. We argue that ‘Divyang’ must be situated within the complex history that conversations around deep pluralisms and diversities have inaugurated. Since ‘Divyang’ is birthed within the Hindutva ecosystem and absorbed into governmental modalities to posit a homogenous category of the disabled, it is shaped and structured by the exclusions of Hindutva.

It would be pertinent to ask how the maiming produced by the quotidian, narrow Hindu nationalist politics of Hindutva impacts the disenfranchisement of persons with disabilities. We must situate the term ‘Divyang’ within what Shruti Kapila calls ‘the eruption of a new fraternity’ imagined by Hindutva politics, which sees ‘key enmity’ with Muslims as a binding factor among Hindus.

The proliferation of borderlands holds the disabled within words that do not reflect lifeworlds. Further, the exclusion insidiously fuels further maiming—whether through war or neglect or erasure or denial of voice and visibility. The terms of engagement indicated by catchwords like ‘Divyang’, emptied of political heft and recognition, replace moral responsibility and human and political agency with abject surrender to divinity that reflects the conditionalities of acquiescence and forced consent of the disabled.

The judiciary as the gladiator of hermeneutical justice

Sitaare Zameen Par presents a narrative in which the judiciary is presented as the gladiator of hermeneutic justice and as an institution of empathy for the disabled. The film begins with a case of drunken driving where basketball coach Gulshan Arora, played by Aamir Khan, is produced in court after crashing into a police vehicle and verbally abusing the policemen who intercept him. The woman judge orders him to do community service as a coach for persons with intellectual disabilities.

The conversation goes as follows (translated from Hindi):

Judge: Do you know about people with ‘intellectual disabilities’?

Arora: You mean mad (‘pagal’) people?

Judge: ‘Intellectual disability’—meaning people who are different because their mental and physical growth is affected by intellectual disability. When you speak about them, you must use appropriate words.

…

Judge: Gulshan Arora is ordered to coach a team of intellectually disabled persons in basketball.

Arora: Madam, how will I teach mad people for three months?

Judge (looking disapprovingly):….and Rs. 500 fine.

Arora: Rs. 500 for saying ‘pagal’?

Judge: Rs. 1000.

Arora: But everyone calls them ‘pagal’!

Judge: Rs. 2000.

Gulshan Arora: What is the big deal about saying ‘pagal’?

Judge (banging the gavel loudly): Rs. 5000.

Sitaare Zameen Par’s depiction of the judiciary as the protector of disabled citizens reflects the ‘mainstream’ disability movement’s reliance on courts for relief and rights enforcement. But these depictions and this valorisation of the role of the courts see disability justice in silos and reproduce the public imagination of the ability-disability binary.

The fact remains that our courts have evaded problematising ‘Divyang’ for the last ten years. The Supreme Court’s Handbook Concerning Persons with Disabilities has a list of terms it considers ‘stereotype perpetuating’, but it does not see ‘Divyang’ as patronising. In M. Karpagam v The Chief Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities, a two-judge Bench of the Madras High Court patronisingly asked a petitioner challenging the use of ‘Divyang’ to stop following ‘the fad of political correctness.’

While we do not have the space to explore the possibilities of the ‘jurisprudential-aesthetic approach’ that legal scholar Oishik Sircar proposes, the intertwining of the aesthetic dimensions of legal texts (judgements and directives in this case) and the jurisprudential dimensions of cinema that he speaks of as co-constitutive are relevant to questions we raise.

In Om Rathod v The Director General of Health Services (2024), the Supreme Court highlighted the importance of fraternity and ‘a progressive grundnorm that seeks to eschew…societal prejudices and biases.’ The Court also linked national progress with the collective outcome based on non-discrimination for disabled citizens.

However, basing fraternity for the disabled on the collective outcome or imagination of the nation often results in the production of the prescriptive disabled citizen of crip nationalist variety that seeks accommodation in medical admission, air travel and other middle-class issues but does not challenge the narrative of the State or the dominant publics.

Disabled persons like the late Professor Saibaba, the late Father Stan Swamy and Hem Mishra—all arrested by the State for alleged links to Maoists—remain outside the category of this prescriptive model of ‘the disabled’, since in the statist framework, the juxtaposition of ability-disability intersects with other binaries that oust them from the nationalist and fundamentalist imagination.

The role of the court must also be appraised on the question of debilitation, which is the endemic condition based on the policies and the politics of exclusion. In Om Rathod, the Supreme Court affirmatively cited Talila A. Lewis’ framework, which suggests that ableism that assigns value to people’s bodies and minds is rooted in ‘eugenics, anti-blackness, misogyny, colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism.’ In the Indian context, caste and the precarious situation of religious minorities remain the sites of strident ableism, where the Court’s performance has not been exemplary.

Were the Muslim characters of Sitaare Zameen Par (Golu Khan and Karim Qureshi) real, one wonders whether they would have had protection from the maiming and debilitation caused by Hindutva politics in constitutional contestations. Much like another fictional protagonist, Manto’s Toba Tek Singh, they would have been stranded between fenced constitutional borderlands, reproducing Ambedkar’s anguish at not having a homeland in a different context.

Vijay K. Tiwari is an Assistant Professor (Law) at The West Bengal National University of Juridical Sciences, Kolkata; Kalpana Kannabiran is a sociologist based in Hyderabad and Distinguished Professor, Council for Social Development, New Delhi.