Analysis

Maratha Reservation & Judicial Review I

The Maratha Reservation case offers yet another opportunity for the Court to lay down the law relating to SEBC reservations

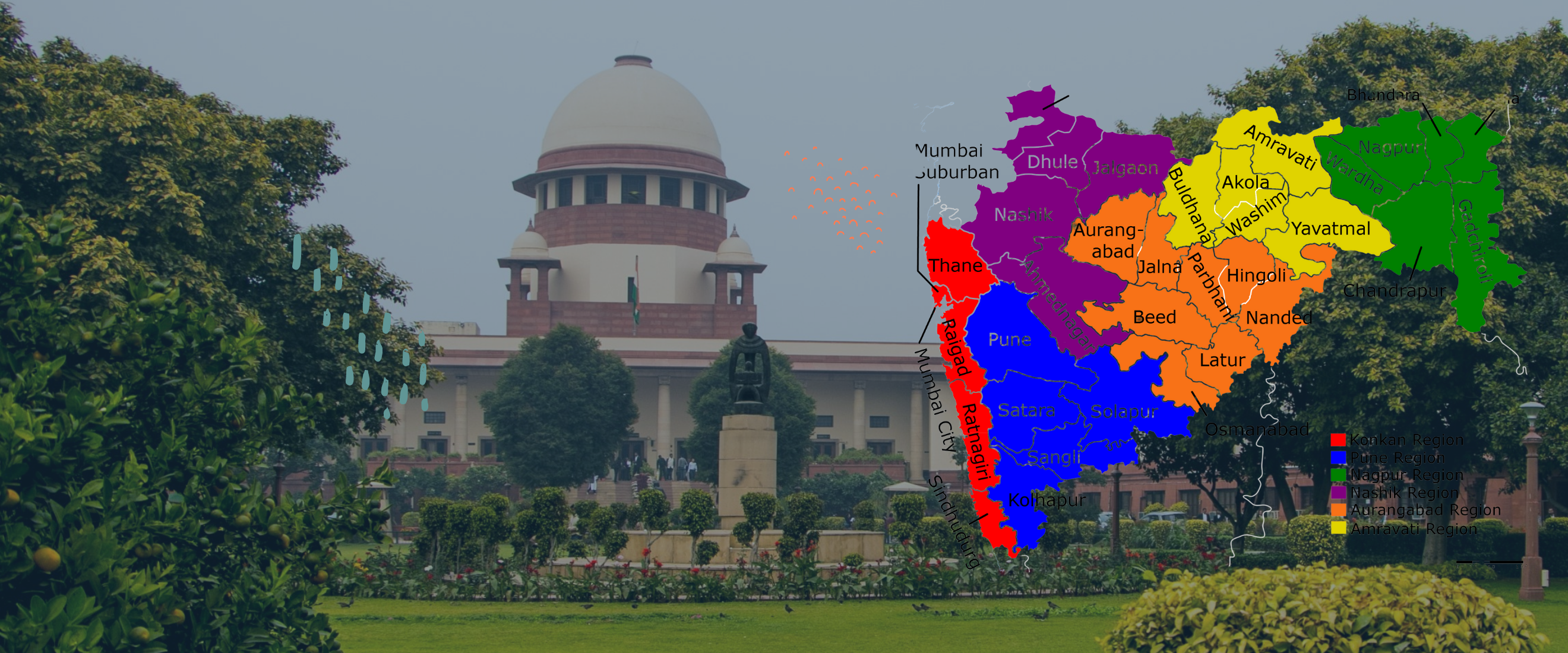

In July 2019, a batch of Petitions was filed in the Supreme Court against the judgment of the Bombay High Court upholding the Maharashtra State Reservation (of seats for admission in educational institutions in the State and for appointments in the public services and posts under the State) for Socially and Educationally Backward Classes Act, 2018 (‘SEBC Act’). The SEBC Act provides 16% reservation for the Maratha community in educational institutions, and public services in the State of Maharashtra. Although the final arguments in the Supreme Court are yet to commence, the Court declined to stay the operation of the Act in the interim.

The case provides yet another opportunity for the Court to lay the contours of the law relating to reservation for Socially and Educationally Backward Classes. In order to do this, it will have to first examine whether the SEBC Act was a legislative overruling of an earlier Bombay High Court order staying the operation of SEBC’s predecessor law. The Court will also have to determine the extent to which it can review the policy decision of the State Government to provide reservation.

The Court had the opportunity to examine these questions in its recent decisions in BK Pavitra- II and Jarnail Singh. In this two-part post, we will provide you a brief history of the current litigation, followed by a discussion of the law vis a vis the above two questions.

History of the litigation

In 2014, the Maharashtra Government passed the Maharashtra State Reservation (of seats for admissions in educational institutions in the State and for appointments or posts in the public services under the State) for Educationally and Socially Backward Category (ESBC) Ordinance, 2014 providing 16% reservation for the Maratha community in education and public employment. The Ordinance though was stayed by the Bombay High Court.

Soon thereafter, the State legislature passed the ESBC Act of 2014 providing the same benefits to the community as the Ordinance. Nevertheless, the Bombay High Court, on April 7th 2016, stayed the operation and implementation of the ESBC Act. As per the Court, the Act was passed without sufficient evidence of the Maratha community’s backward status.

MSBCC and the second round of litigation

During the litigation, the Government set up the Maharashtra State Backward Class Commission (MSBCC) under the chairmanship of Justice Gaikwad. The Committee found that the Maratha community was socially and educationally backward and had inadequate representation in public employment. Therefore, it recommended reserving 12 and 13% seats respectively in education and public employment.

Subsequent to the report, the Government enacted the SEBC Act, 2018. The Act went slightly beyond the MSBCC recommendation and provided 16% reservation to the community in public education and employment. The SEBC Act was then challenged on the grounds that: (1) the scheme of reservation under the Act had already stayed by an earlier order and the Act went against this order, and (2) Government did not have sufficient quantifiable data to recommend reservation. The Petitioners also raised a number of other grounds to contest the validity of the SEBC Act.

The Bombay High Court rejected both these contentions. It held that the Government had removed the inherent defect – lack of quantifiable data to determine the backwardness of the community – which plagued the earlier ordinance and the Act. As to the second contention, it held that the MSBCC had produced a detailed report with quantifiable data on the backwardness of the Maratha community. Nevertheless, the Court directed the Government to bring the quantum of reservation in line with what was recommended by the MSBCC.

Can court decisions be nullified through a law?

As discussed above, the Bombay High Court had stayed the reservation scheme on two occasions when the Ordinance and the ESBC Act were passed. The Government, through another law – SEBC Act, brought back the same scheme a few years later.

The general principle is that the legislature cannot make a law to directly overrule a decision of the Court. But, it has the power to remove the inherent defects which led the court to strike down a law. For example, the legislature cannot pass a law stating that the court’s stay order is flawed and that it is re-introducing the reservation scheme. Nevertheless, it can ‘cure’ the defects found by the court in the law. For instance, if one of the defects found by the Bombay High Court in its earlier order was that the reservation scheme was made without undertaking a proper study of backwardness, the legislature may cure this defect by setting up an expert panel to do such study.

The Supreme Court in BK Pavitra – II dealt with a scenario where the Karnataka Government re-introduced reservation for SC/STs in promotions, even though a similar scheme was struck down by the Court in BK Pavitra – I. Nevertheless, the Court found that this time around, the legislation had been cured of the defects identified earlier, namely the lack of quantifiable data. This, the Court held, was not an encroachment on judicial power:

“The decision in B K Pavitra I did not restrain the state from carrying out the exercise of collecting quantifiable data so as to fulfill the conditionalities for the exercise of the enabling power under Article 16 (4A). The legislature has the plenary power to enact a law. That power extends to enacting a legislation both with prospective and retrospective effect. Where a law has been invalidated by the decision of a constitutional court, the legislature can amend the law retrospectively or enact a law which removes the cause for invalidation. A legislature cannot overrule a decision of the court on the ground that it is erroneous or is nullity. But, it is certainly open to the legislature either to amend an existing law or to enact a law which removes the basis on which a declaration of invalidity was issued in the exercise of judicial review. Curative legislation is constitutionally permissible. It is not an encroachment on judicial power.”

Thus, the Supreme Court, when it hears the final arguments in the Maratha Reservation case will have to decide whether the SEBC Act was an encroachment on judicial power or was merely curing a defect. In other words, it would have to determine if the SEBC Act is a ‘curative legislation’, as discussed in BK Pavitra – II.

In the next part, we will discuss the extent to which the Court can review the findings of the Gaikwad committee report.