Analysis

Sedition: A Hidden Contradiction

DESK BRIEF: The test for sedition contains both the 'clear and present danger' and 'bad tendency' tests from SCOTUS law.

1919 was a defining year for free speech in the United States. Two Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) judgements shaped free speech and decided its limits.

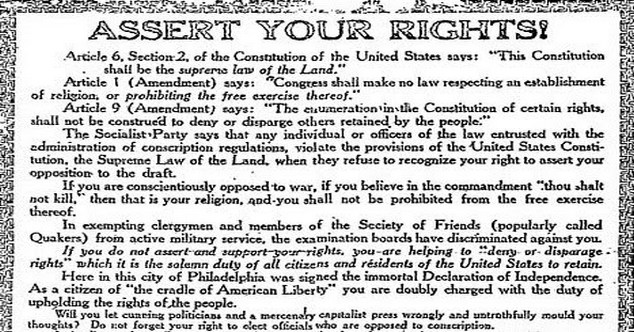

Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer were socialists who argued against compulsory military drafting. They created and distributed leaflets claiming that it violated constitutionally protected rights against servitude. The lower court convicted both under the Espionage Act, 1917. They appealed to SCOTUS. The fundamental right to free speech under the First Amendment covered their right to create and distribute anti-draft messages, they urged. SCOTUS unanimously upheld their conviction.

J. Holmes crafted one of his most famous opinions and laid down the ‘clear and present danger’ test: a clear, proximate and direct link between speech and incitement to violence is a requirement to curb free speech. However, due to the demands of wartime, the Court had to allow the Government some flexibility.

“If you do not assert and support your rights, you are helping to ‘deny and disparage rights’ which it is the solemn duty of all citizens and residents of the United States to retain.”

In the same year, SCOTUS had to decide a similar case. Abrams and his companions were convicted for espionage. They were distributing leaflets condemning America’s war with Russia and denouncing production of ammunition earmarked for the war. SCOTUS agreed with the government and came up with the ‘bad tendency test’. This allows for free speech to be restricted on the ground of public order even if violence is a remote outcome.

For decades now, the key conflict in free speech regulation, across the globe, has been between variations of the ‘clear and present danger test’ and ‘bad tendency test’. How proximate should the possibility of violence be to curb free speech?

Back home, the Supreme Court of India invoked both these cases in Kedar Nath Singh v State of Bihar (1962). In Kedar Nath, the Court upheld S. 124A of the Indian Penal Code,1860. They categorically declared that sedition did not violate free speech. However, the Court did mandate that sedition could be charged only when the act/speech is proximate to violence.

Specifically, it held that ‘incitement to offense’ and ‘intent or tendency to cause disorder’ can lead to sedition. Our post argues what many may have missed- an internal contradiction on free speech regulation. Kedar Nath retains both the ‘bad tendency’ and the ‘clear and present danger’ test to determine the seditious nature of speech.

With the ongoing hearings on the constitutionality of sedition, the Supreme Court has an opportunity to clarify what test to adopt, if it is not struck down. They may also crystallise parameters to regulate free speech.

We discuss the contradictions in understanding free speech regulation here.

We are tracking the Constitutionality of Sedition case here.