Analysis

The Farmers’ Protests and the Court: A Recap

The Union announced the repeal of the farm laws, but the SC has not decided on its constitutionality and the scope right to protest.

In September 2020 Parliament passed three farm laws in an attempt to liberalise the Indian agricultural sector. These laws, the government argued, would bring efficiency to the agricultural markets and increase farmer income.

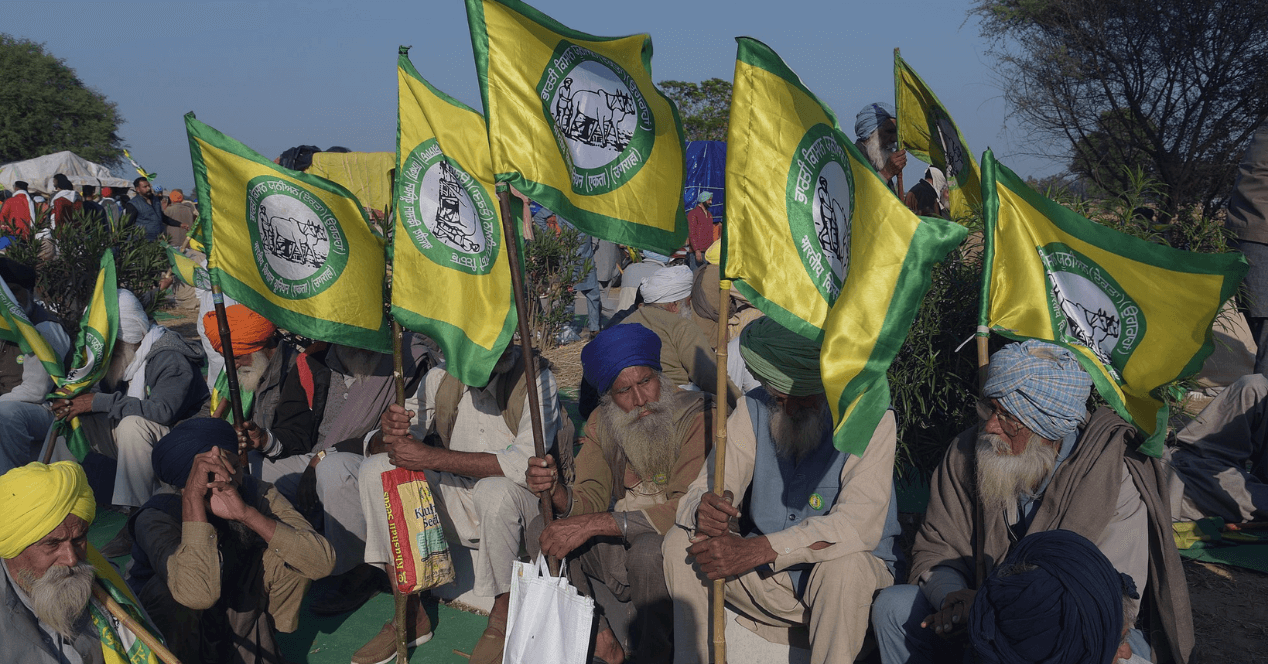

Significant sections of India’s farmers however were not convinced. They argued that the laws allowed private players to dictate prices and production. Starting August 2020 (when the bills were made public), farmers in Punjab and Delhi mounted widespread protests against the farm laws attracting media and political attention. These protests lasted over a year.

On November 19th, 2021 Prime Minister Modi in a televised national address, reminiscent of demonetisation, announced that these laws will be repealed. This came in the wake of the failure of negotiations between the government and the farmers, and protest related violence.

In this post, we highlight the key inflections in the farm law story with a particular focus on the Supreme Court’s involvement and what the repealing of the law means.

Farmers’ Concerns

During the 60s and 70s, state governments began introducing Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) to regulate prices and trade practices. The APMCs created rules for the management of wholesale agricultural markets (or mandis). These regulated mandis are heavily relied upon by farmers for protection against fluctuating prices for their produce.

The new farm laws proposed three significant changes: first they facilitate the trade of agricultural produce outside of these mandis. This means that any price regulation (such as a minimum support price) imposed by APMCs would not apply, exposing farmers to highly volatile market prices. Second, they allow contract farming, where production can be specifically tailored to the buyer’s order, allowing private companies to control farm land and production. And third, they allow private entities to store essential commodities for emergencies (such as natural calamities or war) which only government authorised agents previously could.

Farmers and labourers protested in the outskirts of Delhi for months, seeking these laws to be repealed. Attempts at negotiations failed, with the farmer unions claiming that the key issues were still not being addressed by the government.

Farm Laws Challenged at the Supreme Court

Soon, opposition to the farm laws reached the Supreme Court. Multiple petitions were filed challenging the constitutionality of the farm laws. For four months, the Court passed no substantial order regarding the challenge and protests continued. Then, on January 12th 2021, the Court stayed the farm laws, even though none of the parties had sought such an order.

The Court also set up a committee to negotiate between the Union and the farmers. The committee submitted their report on March 19th 2021 despite eight major farmers unions refusing to participate in the deliberations. The Court did not take any substantive action based on this report.

The Court made no progress in deciding if the farm laws were constitutional since issuing its stay Order in January 2021. Share on X

Since September 2020, when the matter was brought before the Court, more than 600 lives have been lost. Protests in Delhi on Republic Day turned violent, provoking tear gas deployment, and death of one protester. Later, in October, four farmers were mowed down by three vehicles in Lakhimpur Kheri, Uttar Pradesh. These instances sparked outrage and brought further public attention to the ‘right to protest’.

The SC Pivots on the Right to Protest

Since August 2020, protesters have gathered on the outskirts of Delhi, asking for these laws to be repealed. The residents of Delhi-NCR filed several PILs against the protests. The Court heard the matter, and passed an Order on December 17th 2020 recognising the farmers’ right to protest.

Prior to Republic Day when violence broke out in Delhi, the Delhi Police filed an application seeking an injunction against a rally proposed for the day. The Court emphasised that they will not “stifle a peaceful protest”, after which the application was withdrawn.

Seven months later, on July 17th 2021, a body of farmers called the Kisan Mahapanchayat filed a petition seeking permission to protest in Jantar Mantar, Delhi. A Bench constituted by Justices A.M. Khanwilkar and C.T. Ravikumar, heard the petition. This time, the Court pivoted its disposition towards the protests and criticised the protesters for not trusting the Court. They questioned whether the right to protest is an absolute right, especially when a legal remedy has already been sought.

Unanswered Constitutional Questions

On November 19th 2021, Prime Minister Modi unexpectedly announced that the farm laws would be repealed in the Parliament’s winter session. After over a year of protesting, failed negotiations, and violence, this news has come as a relief to many. However, some believe this is a politically motivated move affected by two key events- the violence and protests in Lakhimpur Kheri; and the upcoming elections in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

If the farm laws are repealed, the challenge before the Supreme Court will be infructuous. While the repeal provides closure on the issue at hand, there is no clarity from the Court as to whether these laws would be unconstitutional.

Arguably, the Supreme Court’s delay in hearing the matter has left the issue to be resolved by political forces. The lack of constitutional clarity has potentially opened the doors for the Union government to bring back the same or altered form of these laws in the future.

* The three farm laws are the Farmers (Empowerment & Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance & Farm Services Act, 2020, Farmers Produce Trade & Commerce (Promotion & Facilitation) Act, 2020 and Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020