Court Data

Which languages is the SC translating judgments into?

Out of the 232 translations published on the official website between 1 January 2019 and 29 February 2020, 114 of them were in Hindi.

Article 348 of the Constitution dictates that all Supreme Court proceedings ‘shall be in the English language‘. While this does allow the Court to operate efficiently, it also restricts its accessibility. As the Supreme Court itself has recognised in its Annual Report 2018-19 (pg. 88), many litigants are not well-versed in English. To address this language barrier problem, the Supreme Court plans to make judgments available to litigants in their vernacular language.

The Court intends to make translations available for cases that fall into the below 14 ‘subject categories‘. It reasons that ‘the litigants in relation to these categories of cases, by and large, belong either to the lower or middle strata of the society and are considered to be not well-versed with English language‘ (Annual Report, pg. 88).

- Labour matters

- Rent Act matters

- Land Acquisition and Requisition matters

- Service matters

- Compensation matters

- Criminal matters

- Family Law matters

- Ordinary Civil matters

- Personal Law matters

- Religious and Charitable Endowments matters

- Simple Money and Mortgage matters

- Eviction under the Public Premises (Eviction) Act matters

- Land Laws and Agricultural Tenancies matters

- Consumer Protection matters

Currently, the Supreme Court Registry lacks the capacity to translate all judgments that fall into these categories. Nevertheless, it has begun the process. In 2019 alone, it published translations of 229 judgments on the Supreme Court website.

Distribution of Translations across Vernacular Languages

So which languages is the Registry translating judgments into? We looked at the translations published on the Supreme Court’s website and mapped their distribution. For this preliminary study, we limited ourselves to judgments delivered between 1 January 2019 and 29 February 2020.

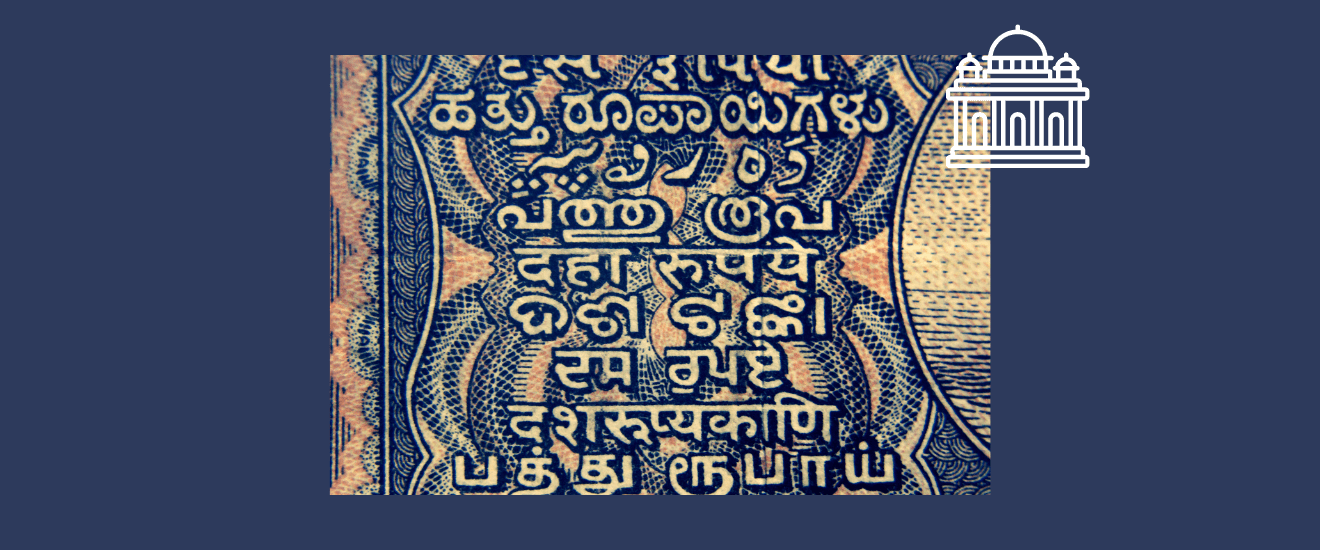

As Figure 1 shows, the vast majority of translations are into Hindi. Out of the 232 translations published on the official website (for the selected period), 114 of them were in Hindi. This is nearly 50% of the total translations. South Indian languages also featured prominently. Out of the total, 31.03% of the translations were in Kannada, Malayalam, Tamil or Telugu.

The three languages that featured least frequently were Bengali, Nepali and Urdu. For the selected period, the Registry only produced 1 translated judgment for each of these languages.

Further, it published no translations at all into some languages in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution (contains the 22 official Indian languages). For example, none of the translated judgments published on the website are in Gujarati. These omitted languages have not been included in Figure 1.

Connection to Language Frequency

There appears to be a connection between the distribution of translations and how commonly a language is spoken in India. In Figure 2, we compare the above distribution to the data in the 2011 Census of India. The 2011 Census approximates how many people speak each Eight Schedule language. It records the number of persons who label each Eight Schedule language as their mother tongue.

The Census defines a mother tongue as ‘the language spoken in childhood by the person’s mother to the person‘. For persons who had no mother growing up, it considers the mother tongue to be whichever language was ‘mainly spoken in the person’s home‘ during childhood (pg. 3).

Figure 2 captures the proportional distribution of the mother tongue and translation data. For example, consider that the ‘Hindi’ row in ‘SC Translations’ is 49.14%. This represents the fact that out of the total number of translated judgments (232 judgments), 49.14% of them are in Hindi (114 judgments). The formula for the left column, ‘2011 Census’, works in the same way. The percentage for each language represents the number of mother tongue speakers for that language, divided by the total number of mother tongue speakers surveyed. For the 2011 Census, the total number of recorded mother tongue speakers (of Eight Schedule Languages) was 1.17 billion.

The chart below shows that there is a relationship between how frequently a language is spoken and how frequently a judgment is translated into that language. Notably, by far the most common language both for mother tongue and translation frequency, is Hindi – 45.12% and 49.14% respectively. Further, both columns follow the same pattern with minor peaks around Marathi, Tamil and Telugu.

While the two distributions share common patters, there are some notable differences. Firstly, some languages that are commonly spoken (relatively) have very few to no translations. In particular, Bengali, Gujarati and Urdu are under-represented. While Bengali is recognised by 8.3% of Census respondents as their mother tongue, only 0.43% of the translated judgments are in Bengali. Gujarati and Urdu are the mother tongues of 4.74% and 4.34% of respondents respectively. However, 0 of the published judgments were in Bengali and only 0.43% of them were in Urdu.

Another notable discrepancy is that the South Indian languages, with the exception of Telugu are over-represented. 6.9%, 6.9% and 11.21% of the translations are in Kannada, Malayalam and Tamil respectively. This is roughly double the proportion of mother tongue speakers. Only 3.73%, 2.97% and 5.89% of respondents reported Kannada, Malayalam and Tamil as their mother tongues respectively.

It is unclear what the cause of these discrepancies may be. One possible explanation may lie in the relative socio-political influence associated with these languages. Perhaps the more influence speakers of a language hold, the more pressure they can assert on the Court to produce translation in their language. Alternatively, the explanation may lie on the supply-side, namely in the capacity of the Registry. It is possible that the Registry is more capable of producing translations in certain languages over others, due to for example, the availability of translators.

Whatever the causes of these discrepancies may be, the fact remains that there appears to be a correlation between how common a language is and the likelihood a judgment being translated into it. After all, the Court’s primary aim in translating judgments is to make them more accessible to litigants, not the public at large. One interesting question that follows is whether this distribution of translations can give us any insight into the types of litigants who are approaching the Supreme Court. Does the mother-tongue distribution of litigants map on to that of Indians in general? Or are certain language-speakers more easily able to access the Supreme Court?