Convict Entitled to Immediate Release After Completion of Life Sentence

Sukhdev Yadav v State of (NCT of Delhi)

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that a convict sentenced to life imprisonment for a fixed term is entitled to immediate release upon completing the term, without having to apply for remission. Detention beyond this period violates Article 21 of the Constitution.

Sukhdev Yadav was serving a sentence of life imprisonment for 20...

Case Details

Judgement Date: 12 August 2025

Citations: 2025 INSC 969 | 2025 SCO.LR 8(3)[12]

Bench: B.V. Nagarathna J, K.V. Viswanathan J

Keyphrases: Keywords/phrases: Section 432 read with 433A of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973—remission—life imprisonment without remission—immediate release after completion of sentence—no remission application after completion of sentence

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

NAGARATHNA, J.

1. Leave granted

2. The salient question that arises in this appeal is, whether, an accused/convict who has completed his “life imprisonment for a fixed term” such as twenty years of actual sentence without remission, as in the instant case, is entitled to be released from prison on completion of such a sentence. In other words, on completion of the fixed term of sentence as aforesaid, should the accused/convict seek remission of his sentence of “life imprisonment” by making an application to the competent authority for seeking “reduction of his sentence”.

Background Facts:

3. By the impugned order dated 25.11.2024, the learned single Judge of the Delhi High Court in W.P. (Crl.) No.1682 of 2023 rejected the petition filed under Article 226 of the Constitution of India seeking release of the appellant on furlough for a period of three weeks considering the apprehension expressed by the complainant i.e. mother of the deceased victim and respondent No.3 herein.

3.1 Being aggrieved by the said order dated 25.11.2024, the appellant has preferred this appeal.

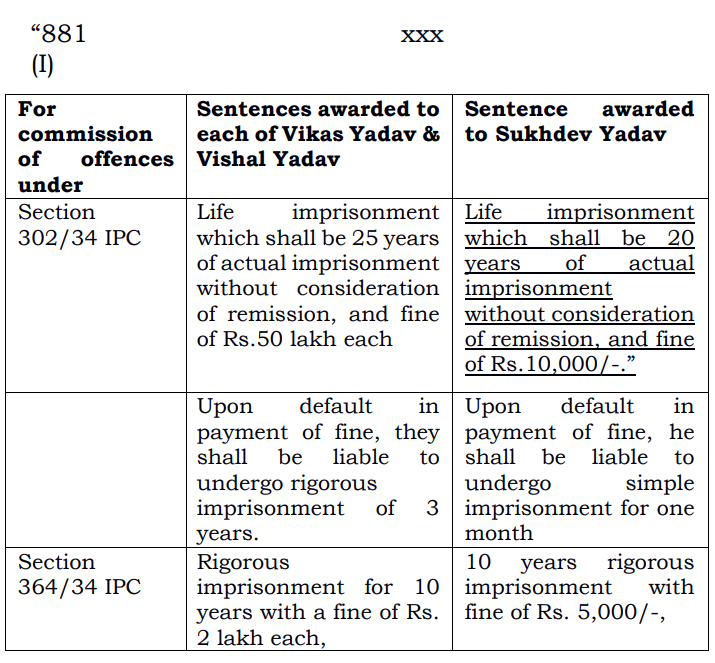

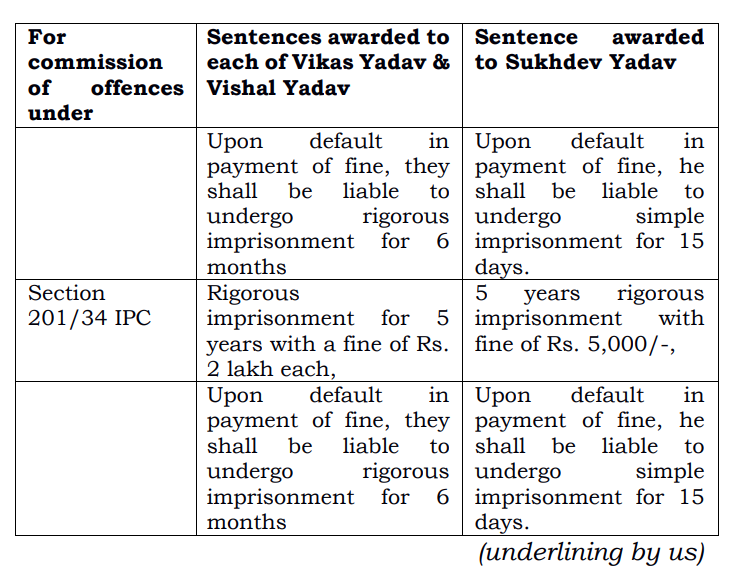

3.2 The relevant facts of the case are that on 17.02.2002, FIR No.192/2002 was registered at P.S. Kavi Nagar, District Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh under Section 364/34 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (hereinafter, “IPC”) on the basis of a complaint filed by Smt. Nilam Katara i.e. complainant and mother of the deceased. On 28.05.2008, after completion of investigation and trial, his co-convicts – Vikas Yadav and Vishal Yadav – were convicted for commission of offences under Sections 302, 364, 201 read with Section 34 of the IPC in SC No.78/2002 by the Additional Sessions Judge (01), New Delhi, (“Sessions Court”). Thereafter, they were sentenced to undergo life imprisonment as well as fine of Rs.1,00,000/- each under Section 302 of the IPC and in default of payment of fine, to undergo simple imprisonment for one year. They were sentenced to rigorous imprisonment for ten years and fine of Rs.50,000/- each for their conviction under Section 364/34 IPC and in default of payment of fine, to undergo simple imprisonment of six months, and rigorous imprisonment for five years and fine of Rs.10,000/- each under Section 201/34 IPC and in default of payment of fine, to undergo simple imprisonment for three months. All sentences were to run concurrently.

3.3 On 06.07.2011, the appellant herein was found guilty of commission of offences under Sections 302, 364, 201 read with Section 34 of the IPC in SC No.76/2008 by the Sessions Court. Subsequently, on 12.07.2011, the appellant was sentenced to undergo life imprisonment and fine of Rs.10,000/- for commission of the offence under Section 302 IPC and in default of payment of fine to undergo rigorous imprisonment for two years; rigorous imprisonment for seven years and fine of Rs.5,000/- for commission of the offence under Section 364 IPC, and in default of payment of fine, rigorous imprisonment for six months; rigorous imprisonment for three years and fine of Rs.5,000/- for his conviction under Section 201 IPC and in default of payment of fine, rigorous imprisonment for six months. All sentences were to run concurrently.

3.4 Aggrieved by their conviction, the co-convicts and the appellant herein preferred criminal appeals before the High Court of Delhi. By judgment dated 02.04.2014, the Criminal Appeal No.145/2012 preferred by the appellant herein was dismissed by the High Court of Delhi and his conviction was upheld. During the pendency of the aforesaid appeals, the State had also preferred Criminal Appeal No.1322/2011 against the appellant along with Criminal Appeal No.958/2008 against the co-convicts seeking enhancement of sentence of life imprisonment to imposition of death penalty. The complainant had also preferred Criminal Revision Petition No.369/2008 against the order of the Sessions Court, seeking enhancement of sentence for all convicts including the appellant herein. By judgment dated 06.02.2015, the High Court disposed of all appeals and the revision petition by modifying the sentence imposed upon the appellant by judgment and order dated 12.07.2021 and directed that he shall undergo the sentence as extracted hereunder:-

(II) It is directed that the sentences for conviction of the offences under Section 302/34 and Section 364/34 IPC shall run concurrently. The sentence under Section 201/34 IPC shall run consecutively to the other sentences for the discussion and reasons in paras 741 to 745 above.

(III) The amount of the fines shall be deposited with the trial court within a period of six months from today.

xxx

(V) Amount of fines deposited by Sukhdev Yadav and other fines deposited by Vikas Yadav and Vishal Yadav shall be forwarded to the Delhi Legal Services Authority to be utilized under the Victims Compensation Scheme.

(VI) In case an application for parole or remission is moved by the defendants before the appropriate government, notice thereof shall be given to Nilam Katara as well as Ajay Katara by the appropriate government and they shall also be heard with regard thereto before passing of orders thereon.”

3.5 Aggrieved by the order of the High Court, the appellant herein preferred Criminal Appeal Nos.1528-1530/2015 before this Court which, along with appeals preferred by co-convicts, was disposed of by a common judgment dated 03.10.2016, with a singular modification in the sentence, i.e. the sentence under Section 201/34 IPC shall run concurrently.

3.6 Since the year 2015, the appellant herein has been intermittently granted parole for short periods. On 30.11.2022, the appellant moved an application seeking grant of first spell of furlough for a period of three weeks as per Rule 1223 of the Delhi Prison Rules, 2018 (for short, “2018 Rules”) before the Director General of Prisons, Prison Headquarters, Tihar (hereinafter, “Competent Authority”). However, the same came to be rejected vide order dated 28.04.2023 considering the nature of crime committed, the sentence awarded and apprehension that the appellant may abscond, disturb law and order and cause irreparable damage to the victim’s family.

3.7 Aggrieved by the order rejecting the application for grant of furlough, the appellant filed Writ Petition Criminal No.1682/2023 before the High Court of Delhi seeking a writ of mandamus directing the State to release the petitioner on furlough for a period of three weeks. By impugned order dated 25.11.2024, the writ petition preferred by the appellant was dismissed by the High Court on the ground, inter alia, that there were serious apprehensions with regard to threat to life and liberty of the complainant and the star witness.

4. Hence, this appeal.

5. By Order dated 06.01.2025, this Court issued notice in the instant matter. During subsequent hearings, this Court passed the following order on 24.02.2025:

“We have perused the judgment of the High Court dated 6th February, 2025 in Criminal Appeal No.145 of 2012. As regards the sentence awarded to the petitioner, in paragraph 881 of the operative part of the judgment, it is stated thus:

“Life imprisonment which shall be 20 years of actual imprisonment without consideration of remission, and fine of Rs.10,000/-.”

The learned Additional Solicitor General appearing for the respondent State of Delhi states that even after completion of 20 years of actual imprisonment, the State Government will not release the petitioner, notwithstanding what is stated in paragraph 881 of the judgment of the High Court which has attained finality.

We direct the Secretary of the Home Department of the State of NCT of Delhi to file an affidavit making a statement on oath on the question whether after completing 20 years of actual sentence, the petitioner will be released. An affidavit to be filed by 28th February, 2025.

List on 3rd March, 2025.”

(underlining by us)

5.1 On 03.03.2025, this Court adjourned the matter for two weeks on the assurance of the learned Additional Solicitor General (ASG) appearing for the State that the case of the appellant for remission shall be considered and decided within a period of two weeks from the date of the order. However, as the same was not done by the next date of hearing i.e. 17.03.2025; this Court issued notice to the Principal Secretary of the Home Department of Delhi Government calling upon him to indicate why action under the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971 should not be initiated against him. The order of this Court recorded as follows:

“A solemn statement on instructions of the State Government was recorded in this order. Now we are informed that Sentence Review Board is likely to consider the case of the petitioner today. The State Government has not shown elementary courtesy of making an application for grant of extension of time.

We, therefore, issue notice to the Principal Secretary of the Home Department of Delhi Government calling upon him to show why action under the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971 should not be initiated against him.

Notice of contempt is made returnable on 28th March, 2025. We direct the Secretary to remain present through video conference.”

5.2 Pertinently, during the pendency of the instant appeal, the appellant completed twenty years of actual incarceration on 09.03.2025.

5.3 On 28.03.2025, this Court listed the matter on 22.04.2025 for considering the issue whether the appellant is entitled to be released on completion of actual twenty years of incarceration. However, on 22.04.2025, despite its clear and advance notice to all parties that this Court will consider the aforesaid substantive question of sentencing, the learned ASG raised a preliminary objection after a half an hour of arguments that since the appellant had not canvassed this ground in his petition, this Court could not go into the question. In these circumstances, the appellant was directed to file an amended petition within three days from the date of the order, which recorded as follows:

“The learned senior counsel appearing for the petitioner completed his submissions. The learned ASG appearing for the State of NCT of Delhi, after making submissions for half an hour, raised a preliminary objection that the petitioner has not raised a plea in this Petition that he is entitled to be released after undergoing actual sentence of 20 years. Thus, the submission in short was that this Court cannot go into this question. As indicated in the earlier two orders, which we have quoted above, make it clear that we had put the learned counsel for the parties to the notice that the issue whether the petitioner is entitled to be released on completion of 20 years of incarceration will be considered today. While the learned ASG was arguing, we thought that the Advocates waiting for other cases should not be made to wait as remaining part of the day’s time was likely to be consumed in this case. Therefore, at 3:15 p.m., we discharged the rest of the cases on the cause list and informed the members of the Bar that those cases will not be taken up. Fifteen minutes thereafter, this preliminary objection was raised by the learned ASG. Therefore, raising such a preliminary objection after arguing the case for half an hour especially in the light of the two orders which we have quoted above, is unfair to the other litigants whose cases were listed before this Court today. Since this strong objection has been raised, we permit the petitioner to amend the Petition for raising the contention noted in the earlier orders, though this amendment is strictly not required in view of our earlier orders. We direct the petitioner to file an amended petition within three days from today with an advance copy to the learned counsel representing the respondents.”

5.4 On 07.05.2025, the application seeking permission to amend the special leave petition was allowed by this Court. Having completed twenty years of actual incarceration on 09.03.2025, the appellant also moved I.A. No.147782/2025 seeking release on furlough for a suitable period during the pendency of instant special leave petition. By Order dated 25.06.2025, this Court allowed the application and granted the relief of furlough to the appellant for a period of three months from the date of release, subject to appropriate terms and conditions to be imposed by the learned trial court. The said order reads as under:

“I.A. No.147782/2025 in SLP (Crl.) No.17915/2024

We have heard Shri Siddharth Mridul, learned senior counsel for the petitioner, Mrs. Archana Pathak Dave, learned A.S.G. for the respondent(s)/State and Ms. Vrinda Bhandari, learned counsel for respondent No.2.

This interlocutory application has been filed by the petitioner seeking the relief of his release on furlough for a suitable period during the pendency of the related special leave petition.

Be it stated that the related SLP(Crl) No. 17915/2024 has been preferred by the petitioner against the order dated 25.11.2024 passed by the High Court of Delhi in

W.P. (Crl.) No.1682/2023 [Sukhdev Yadav @ Pehalwan Vs. State (NCT of Delhi] whereby and whereunder prayer of the petitioner for grant of furlough was rejected.

Be it stated that petitioner was convicted by the Trial Court under Sections 302, 364 and 201 read with Section 34 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) and sentenced to undergo imprisonment for life.

In Criminal Appeal No.145/2012, the High Court passed judgment and order dated 06.02.2015 enhancing the sentence of the petitioner to life imprisonment which shall be 20 years of actual imprisonment without consideration of remission and fine of Rs.10,000/-. This order of the High Court has been affirmed by this Court.

Learned senior counsel for the petitioner submits that petitioner had completed 20 years of actual imprisonment without consideration of remission on 09.03.2025. However, prior thereto the related Writ Petition, i.e., W.P. (Crl.) No.1682/2023 was filed before the High Court seeking furlough for a period of three weeks.

As noted above, by the impugned order dated 25.11.2024, the said prayer was rejected.

In the course of hearing of the main SLP, this Court permitted the petitioner to amend the Special Leave Petition incorporating the ground that petitioner’s sentence would come to an end on undergoing 20 years of actual incarceration without remission.

In the hearing today, learned A.S.G very fairly submits that since it is a matter of furlough, Court may consider passing appropriate order. But, at the same time, the security of the informant should also be taken into consideration by the Court as she has already been offered security by the State because of the circumstances surrounding the case.

Learned counsel for respondent No.2 vehemently objects to the prayer of the petitioner. She submits that conduct of the petitioner leaves much to be desired and would not entitle him to any discretionary relief from the Court. In this connection, she has referred to an order dated 06.02.2025 passed by a learned Judge of the High Court in W.P. (Crl.) No.1848/2020 whereby the learned Judge recused herself from hearing the matter observing that attempts have been made to influence the Court.

While such conduct is highly deplorable and condemnable, there is nothing on record to show whether any enquiry was conducted to find out who had indulged in such reprehensible activity. In the absence thereof, it would not be just and proper to deny relief to the petitioner on that count.

After hearing learned counsel for the parties and taking an overall view of the matter, more particularly the factum that petitioner has completed 20 years of uninterrupted incarceration without remission, as ordered by the High Court which was affirmed by the Supreme Court, we are of the view that it is a fit case where petitioner deserves to be released on furlough at least for a limited duration. Of course, necessary conditions would have to be imposed on the petitioner so that liberty of furlough is not misused. That apart, safety and security of respondent Nos.2 and 3 are also required to be protected.

That being the position, we grant furlough to the petitioner for a period of three months from the date of release. Petitioner shall be produced before the learned Trial Court within a maximum period of seven days from today, whereafter the learned Trial Court shall release the petitioner on furlough on appropriate terms and conditions including concerning safety and security of respondent Nos.2 and 3.

The Interlocutory Application is disposed of.

List the matters before the Regular Bench on 29.07.2025, as already ordered.”

6. Admittedly, during the pendency of the appeal before this Court, on 09.03.2025 the appellant has completed his jail sentence inasmuch as he served the sentence which was awarded to him under Section 302/34 of the IPC vide paragraph 881 of the order of the High Court of Delhi dated 06.02.2015. For convenience, the same is extracted as under:

“Life Imprisonment which shall be twenty years of actual imprisonment without consideration of remission and fine of Rs.10,000/-.”

(underlining by us)

Submissions:

7. We have heard learned senior counsel Sri Siddharth Mridul for the appellant and learned ASG Ms. Archana Pathak Dave appearing for the respondent(s)-State and learned senior counsel Ms. Aparajita Singh for the respondent No.2/complainant and perused the material on record.

7.1 It was submitted by learned senior counsel appearing on behalf of the appellant that the appellant has complied with the sentence imposed on him and learned Additional Solicitor General appearing for the respondent(s)-State has also acknowledged the fact that he has completed twenty years of actual imprisonment. In the circumstances, the appellant is entitled to be released on completion of his sentence. Consequently, it was contended that it would be unnecessary to go into the question of the correctness or otherwise of the impugned order dated 25.11.2024 and the appeal may be allowed and disposed of in the aforesaid terms on the basis of the aforesaid admitted facts.

7.2 Learned senior counsel Sri Mridul further contended that although the application filed by the appellant for release on furlough has not been accepted and in fact, the writ petition filed by the appellant under Article 226 of the Constitution has been dismissed by the High Court, the significant fact that on 09.03.2025, the appellant has completed his sentence inasmuch as he has undergone incarceration for twenty years and has also paid the fine would entitle him to be released. Since by interim order dated 25.06.2025, this Court has released the appellant on furlough, the appellant may be stated to have been released from jail on completion of his sentence, if not wanted in any other case.

7.3 Per contra, learned ASG appearing for the respondent-State contended that the appellant has been sentenced to undergo life imprisonment. That the period of incarceration being twenty years is to be construed as the period without remission. However, on completion of the period of twenty years, the Sentence Review Board would have to consider whether the appellant is entitled to be released from jail or not. This would be on remission of his life sentence. That having regard to the serious crime in which the appellant has been convicted of and the fact that he has sustained the sentence of life imprisonment, he cannot straightaway seek release from jail in the absence of any application being made seeking remission of his sentence. In other words, it was contended that it is necessary to consider as to, whether, the appellant is entitled for release from jail at all inasmuch as he has been sentenced to life imprisonment and hence, unless there is an order of remission of sentence passed in favour of the appellant remitting his sentence of life imprisonment, he cannot be released from jail. Therefore, on completion of the period of three months furlough granted by this Court, the appellant has to surrender and return to jail.

7.4 Learned senior counsel appearing for the respondent- complainant also echoed the very same submission and in that regard referred to the judgments of this Court in the case of Navas alias Mulanavas vs. State of Kerala, 2024 SCC OnLine SC 315 (“Navas alias Mulanavas”) and Maru Ram vs. Union of India, (1981) 1 SCC 107 (“Maru Ram”), to contend that the appellant cannot be simply released from jail only because he has completed twenty years of incarceration when in fact he has been sentenced to life imprisonment. It was therefore vehemently submitted by the learned senior counsel for the respective respondents that the appeal would not call for any further consideration and the same may be dismissed.

7.5 By way of reply arguments, learned senior counsel Sri Mridul submitted that there is a distinction between release from jail on completion of sentence of imprisonment and remission of a sentence. He pointed out that remission of a sentence is considered when the sentence is not yet complete whereas release from jail is only upon completion of the period of incarceration that the convict was sentenced to undergo. It is not in dispute that on 09.03.2025, the appellant herein completed his jail sentence of imprisonment being twenty years and therefore was entitled to be released from jail; however, the respondents have raised highly technical and irrelevant submissions before this Court which has delayed the release. Nevertheless, this Court has been pleased to grant a furlough order dated 25.06.2025 only for a period of three months, which implies that he would have to surrender on completion of the said period.

7.6 Learned senior counsel argued that the course of action suggested by the State to be taken in the case of the appellant, that is, the appellant for seeking remission of his sentence must be made by him (which could also be rejected) would be illegal and contrary to the sentence of imprisonment imposed on the appellant and in violation of appellant’s right to liberty. That the submissions of the learned senior counsel for the respondents would tantamount to sitting in judgment over a judicial order imposing the sentence on the appellant herein by the High Court which has been sustained by this Court and, therefore, no other authority can interfere with the sentence imposed on the appellant. Learned senior counsel therefore contended that the appellant would no longer require to plead for remission of a sentence or for furlough in future as he has completed his period of imprisonment being twenty years and is, therefore, entitled to be released on such completion of a sentence, if not wanted in any other case. Learned senior counsel for the appellant submitted that the objections raised by the respondents are wholly unsustainable and therefore, bearing in mind the aforesaid facts, the appeal may be allowed.

8. In light of the aforesaid rival contentions, it is necessary to delineate on the distinction between remission of sentence and release on completion of a sentence of an accused-convict in the case of a life sentence. But before that, it is necessary to understand the meaning of the phrase “life imprisonment”.

Life Imprisonment:

8.1 Section 53 of the IPC speaks about various punishments which could be ordered against the offenders and imprisonment for life is one of such punishment. The said Section reads as under:

“53. Punishments.- The punishments to which offenders are liable under the provisions of this Code are –

First. – Death;

Secondly. – Imprisonment for life;

***[Clause “Thirdly” omitted by Act 17 of 1949, sec. 2

(w.e.f. 6.4.1949].

Fourthly. – Imprisonment, which is of two descriptions, namely :-

(1) Rigorous, that is, with hard labour;

(2) Simple;

Fifthly. – Forfeiture of property;

Sixthly. – Fine.”

Section 57 of the IPC is also relevant and is extracted as under:

“57. Fractions of terms of punishment.– In calculating fractions of terms of punishment, imprisonment for life shall be reckoned as equivalent to imprisonment for twenty years.”

8.2 The expression life imprisonment has been considered in various decisions of this Court which could be adverted to at this stage. In Gopal Vinayak Godse vs. State of Maharashtra, AIR 1961 SC 600 (“Gopal Vinayak Godse”), it was observed that a sentence of imprisonment for life must prima facie be treated as imprisonment for the whole of the remaining period of the convicted person’s natural life. In Ashok Kumar alias Golu vs. Union of India, AIR 1991 SC 1792, it was observed that the expression “imprisonment for life” must be read in the context of Section 45, IPC. Then, it would ordinarily mean imprisonment for the full or complete span of life. In Saibanna vs. State of Karnataka, (2005) 4 SCC 165, it was observed that life imprisonment means to serve imprisonment for the remainder of his life unless sentence is commuted or remitted. It cannot be equated with any fixed term. In Swamy Shraddananda (2) vs. State of Karnataka, (2008) 13 SCC 767 (“Swamy Shraddananda (2)”), it was observed that it is conclusively settled by a catena of decisions that the punishment of imprisonment for life handed down by the Court means a sentence of imprisonment for the convict for the rest of his life. However, further discussion of this case is made later. In Mohinder Singh vs. State of Punjab, (2013) 3 SCC 294, it was observed that life imprisonment cannot be equivalent to imprisonment for fourteen years or twenty years or even thirty years, rather it always means the whole natural life. In Yakub Abdul Razak Memon vs. State of Maharashtra, (2013) 13 SCC 1, it was observed that imprisonment for life is to be treated as rigorous imprisonment for life. It was also observed that life imprisonment cannot be considered as equivalent to imprisonment for fourteen years or twenty years or even thirty years, rather it always means the whole natural life.

8.3 However, in a catena of cases, the punishment of imprisonment for life has been restricted to certain number of years, for instance twenty years or thirty years or thirty-five years. In such a situation, would it mean, on completion of the fixed term of imprisonment, say twenty years as in the instant case, that the accused-convict would have to continue to remain in jail for the remainder of his life or become entitled to be released from jail on completion of the term of twenty years?

8.4 Krishna Iyer, J. in Mohd. Giasuddin vs. State of A.P., (1977) 3 SCC 287, quoted (at SCC p. 290, para 9) George Bernard Shaw, the famous satirist who said, “If you are to punish a man retributively, you must injure him. If you are to reform him, you must improve him and, men are not improved by injuries.” According to him, humanity today views sentencing as a process of reshaping a person who has deteriorated into criminality and the modern community has a primary stake in the rehabilitation of the offender as a means of social defence. Thus, the reformative approach to punishment should be the object of criminal law, in order to promote rehabilitation without offending communal conscience and to secure social justice.

9. In Swamy Shraddananda (2), a three-Judge Bench of this Court considered the question as to how would the sentence of imprisonment for life works out in actuality. This Court pondered over the definition of the word “life” in Section 45 of the IPC which has been defined to denote the life of the human being, unless the contrary appears from the context. Further, whether this Court, which commutes the punishment of death awarded by the trial court and confirmed by the High Court as life imprisonment, would mean literally for life or in any case, for a period far in excess of fourteen years. It was observed that this Court in its judgment may make its intent explicit and state clearly that the sentence handed over to the convict is imprisonment till his last breath or, life permitting, imprisonment for a term not less than twenty, twenty- five or even thirty years. But once the judgment is pronounced, the execution of the sentence passes into the hands of the executive and is governed by the different provisions of law. This Court questioned as to how the sentence of imprisonment for life (till its full natural span) given to a convict as a substitute for the death sentence be viewed differently and segregated from the ordinary life imprisonment given as the sentence of first choice.

9.1 The appellant in the said case, on conviction, was imposed the death sentence, which was confirmed by the High Court. A two-Judge Bench of this Court concurred on the conviction of the appellant but was unable to agree on the punishment to be meted out to him. Sinha, J. felt that in the facts and circumstances of the case the punishment of life imprisonment, rather than death would serve the ends of justice. However, he opined, the appellant would not be released from prison till the end of his life. Katju, J. on the other hand, was of the view that the appellant therein deserves nothing but death penalty. Hence, the matter was referred to a three-Judge Bench.

9.2 Aftab Alam, J. speaking for the three-Judge Bench, after discussing the manner in which the crime was committed referred to the judgments in Machhi Singh vs. State of Punjab, (1983) 3 SCC 470 (“Machhi Singh”) and Bachan Singh vs. State of Punjab, (1980) 2 SCC 684 (“Bachan Singh”). It was observed that in Bachan Singh, the principle of “the rarest of rare” cases was laid down and in Machhi Singh, this Court for practical application, crystallised the principle into five definite categories of cases of murder and in doing so also considerably enlarged the scope for imposing death penalty. It was also observed that in reality in the later decisions neither “the rarest of rare cases” principle nor the Machhi Singh categories were followed uniformly and consistently. Holding that this Court was reluctant to confirm the death sentence of the appellant therein, the question about the punishment being commensurate to the appellant’s crime was considered. Not accepting the fact that life imprisonment could be equated to a term of fourteen years, it was observed that “the answer lies in breaking this standardisation that, in practice, renders the sentence of life imprisonment equal to imprisonment for a period of no more than fourteen years: in making it clear that the sentence of life imprisonment when awarded as a substitute for death penalty would be carried out strictly as directed by the Court.” This Court, therefore, thought it fit to lay down a good and sound legal basis for imposing the punishment of imprisonment for life, when awarded as substitute for death penalty, beyond any remission so that it may be followed in appropriate cases as a uniform policy not only by this Court but also by the High Courts, being the superior courts in their respective States.

9.3 Referring to Sinha, J. order, that a life sentence was meant to be “life sentence”, reference was also made to the judgments of this Court in Subash Chander vs. Krishan Lal, (2001) 4 SCC 458; Shri Bhagwan vs. State of Rajasthan, (2001) 6 SCC 296; Prakash Dhawal Khairnar (Patil) vs. State of Maharashtra, (2002) 2 SCC 35; Ram Anup Singh vs. State of Bihar, (2002) 6 SCC 686; Mohd. Munna vs. Union of India, (2005) 7 SCC 417 (“Mohd. Munna”); Jayawant Dattatraya Suryarao vs. State of Maharashtra, (2001) 10 SCC 109; and Nazir Khan vs. State of Delhi, (2003) 8 SCC 461.

9.4 In the aforesaid seven decisions, this Court modified the death sentence to imprisonment for life or in some case imprisonment for a term of twenty years with a further direction that the convict must not be released from prison for the rest of his life or before actually serving the term of twenty years, as the case may be, primarily on two premises: one, an imprisonment for life, in terms of Section 53 read with Section 45 of the IPC meant imprisonment for the rest of life of the prisoner and two, a convict undergoing life imprisonment has no right to claim remission. In support of the second premise, reliance was placed on the line of decisions beginning from Gopal Vinayak Godse and upto Mohd. Munna.

9.5 In Swamy Shraddananda (2), this Court took note of the contention that to say that a convict undergoing a sentence of imprisonment has no right to claim remission was not the same as the Court, while imposing the punishment of imprisonment, suspending the operation of the statutory provisions of remission and restraining the appropriate Government from discharging its statutory function. It was contended in the said case that just as the Court could not direct the appropriate Government for granting remission to a convicted prisoner, it was not open to the Court to direct the appropriate Government not to consider the case of a convict for grant of remission in sentence. It was contended therein that giving punishment for an offence is a judicial function but the execution of the punishment passes into the hands of the executive and under the scheme of statute, the Court had no control over the execution. This contention was however, not accepted and held to be untenable. Referring to Sections 45, 53, 54, 55 and 57 of the IPC, it was observed that Section 57 provides that in calculating fractions of terms of punishment, imprisonment for life shall be reckoned as equivalent to imprisonment for twenty years. That Section 57 of the IPC does not in any way limit the punishment for imprisonment for life to a term of twenty years. It only provides that imprisonment for life shall be reckoned as imprisonment for twenty years while calculating fraction of terms of punishment. It was observed that the object and purpose of Section 57 would be clear by referring to Sections 65, 116, 119, 129 and 511 of the IPC.

9.6 Discussing on remission, it was pointed out that under the Prison Acts and the Rules for good conduct and for doing certain duties, etc. inside the jail, the prisoners are given some days’ remission on a monthly, quarterly, or annual basis. The days of remission so earned by a prisoner are added to the period of his actual imprisonment (including the period undergone as an undertrial) to make up the term of sentence awarded by the Court.

9.7 Taking note of the way in which remission is actually allowed in cases of life imprisonment, it was found necessary to make a special category for the very few cases where the death penalty might be substituted by the punishment of imprisonment for life or imprisonment for a term in excess of fourteen years and to put that category beyond the application of remission. This Court further observed that if the Court’s option is limited only to two punishments, one a sentence of life imprisonment, for all intents and purposes, of not more than fourteen years and the other death, the Court may feel tempted and find itself nudged into endorsing the death penalty which would be disastrous in certain cases. The Court observed thus:

“A far more just, reasonable and proper course would be to expand the options and to take over what, as a matter of fact, lawfully belongs to the Court i.e. the vast hiatus between 14 years’ imprisonment and death. It needs to be emphasized that the Court would take recourse to the expanded option primarily because in the facts of the case, the sentence of 14 years’ imprisonment would amount to no punishment at all.”

9.8 Consequently, the three-Judge Bench agreed with the view taken by Sinha, J. and substituted the death sentence given to the appellant therein by imprisonment for life and directed that he shall not be released from prison till the rest of his life.

10. Thereafter, the Constitution Bench of this Court in Union of India vs. V. Sriharan, (2016) 7 SCC 1 (“Sriharan”) considered, inter alia, the following two questions:

“(i) As to whether the imprisonment for life means till the end of convict’s life with or without any scope for remission?

(ii) Whether a special category of sentence instead of death for a term exceeding 14 years can be made by putting that category beyond grant of remission?”

10.1 The Constitution Bench speaking through Kalifulla, J.- for the majority- observed that the first question relates to Sections 53 and 45 of the IPC vis-à-vis the meaning of “life imprisonment” as to whether it means imprisonment for the rest of one’s life or a convict has a right to claim remission. The second question is based on the ruling of Swamy Shraddananda (2).

10.2Having noted the judgments of this Court in Gopal Vinayak Godse and Maru Ram as well as other cases discussed therein which have followed those decisions, it was observed that, “The first part of the first question can be conveniently answered to the effect that imprisonment for life in terms of Section 53 read with Section 45 of the Penal Code only means imprisonment for rest of the life of the prisoner subject, however, to the right to claim remission, etc. as provided under Articles 72 and 161 of the Constitution to be exercisable by the President and the Governor of the State and also as provided under Section 432 of the Criminal Procedure Code.”

10.3 On the concept of remission in paragraph 62, it was observed as under:

“62……Similarly, in the case of a life imprisonment, meaning thereby the entirety of one’s life, unless there is a commutation of such sentence for any specific period, there would be no scope to count the earned remission. In either case, it will again depend upon an answer to the second part of the first question based on the principles laid down in Swamy Shraddananda (2).”

(underlining by us)

10.4 With regard to the second part of the first question which pertains to the special category of the sentence to be considered in substitute of death penalty by imposing a life sentence i.e., the entirety of the life or a term of imprisonment which can be less than full life term but more than fourteen years and put that category beyond application of remission which has been propounded in paragraphs 91 and 92 of Swamy Shraddananda (2), it was observed that the said dictum “has come to stay as on this date”.

10.5 Analysing the decision in Swamy Shraddananda (2) and endorsing the same, it was observed that the death penalty in that case was set aside although much anguish was expressed on the nature of the crime and the life sentence for the rest of the life of the convict therein was ordered by this Court. The justification for the same was stated in paragraph 68 of Sriharan in the following words:\

“68. … But in an organised society where the Rule of Law prevails, for every conduct of a human being, right or wrong, there is a well-set methodology followed based on time tested, well-thought out principles of law either to reward or punish anyone, which were crystallised from time immemorial by taking into account very many factors, such as the person concerned, his or her past conduct, the background in which one was brought up, the educational and knowledge base, the surroundings in which one was brought up, the societal background, the wherewithal, the circumstances that prevailed at the time when any act was committed or carried out whether there was any pre-plan prevalent, whether it was an individual action or personal action or happened at the instance of anybody else or such action happened to occur unknowingly, so on so forth. It is for this reason, we find that the criminal law jurisprudence was developed by setting forth very many ingredients while describing the various crimes, and by providing different kinds of punishment and even relating to such punishment different degrees, in order to ensure that the crimes alleged are befitting the nature and extent of commission of such crimes and the punishments to be imposed meets with the requirement or the gravity of the crime committed.”

10.6 After referring in detail to the judgment of this Court in Swamy Shraddananda (2), it was observed that when by way of a judicial decision, after a detailed analysis, having regard to the proportionality of the crime committed, it is decided that the offender deserves to be punished with the sentence of life imprisonment i.e. till end of his life or for a specific period of twenty years, thirty years or forty years, such a conclusion should survive without any interruption. In such an event, it can be stated that such punishment imposed will have no remission or other such liberal approach should not come into effect to nullify such imposition. Accepting the submission of learned Solicitor General that there is no restriction to fix any period beyond fourteen years and up to the end of one’s life span, it was stated that the Court can sentence the accused to undergo imprisonment for a specified period even beyond fourteen years without any scope for remission. The Court can direct that such offender is not to be released early and be kept in confinement for a longer period by imposition of an appropriate sentence.

10.7 Moving further it was observed that nowhere under the IPC is there any prohibition that the imprisonment cannot be imposed for any specific period within the lifespan. Thus, when life imprisonment is imposed, the Court can specify the period up to which the said sentence of life should remain, befitting the nature of the crime committed, when the Court’s conscience does not persuade the death penalty. Therefore, the dictum in Swamy Shraddananda (2) was approved by this Court by observing that within the prescribed limit of life imprisonment, imprisonment for a specified period would be a proportionate punishment having regard to the nature of the crime as well as the interest of the victim.

10.8 Therefore, the law-makers have thought it fit to prescribe the minimum and maximum sentence to be imposed having regard to the nature of crime and have left it to the Courts to determine the kind of punishments that have to be imposed within the prescribed limit under the relevant provision. In other words, while the maximum extent of punishment of either death or life imprisonment is provided for under the relevant provisions, it will be for the Courts to decide if, in its opinion, the imposition of death may not be warranted, what should be the number of years of imprisonment that would be judiciously and judicially more appropriate. This is by taking into account, apart from the crime itself, the interest of the society at large and other relevant factors which cannot be put in any straight jacket formula. The said process of determination must be held to be available with the courts by virtue of extent of the punishments provided for such specified nature of crimes and such power is also to be derived from those penal provisions themselves.

10.9 Further, it was noted that even with regard to the nature of punishment imposed by the Sessions Court insofar as capital punishment is concerned, the reference made to the Division Bench of the High Court is in order to give a second look to the findings arrived by the Sessions Court, both with regard to conviction as well as with regard to the death penalty imposed. In a death reference case, the High Court can commute the death penalty to life imprisonment or for any specific period of more than fourteen years i.e. twenty, thirty or so on, depending upon the gravity of the crime committed and the exercise of judicial conscience vis-à-vis the offences proved to have been committed. In conclusion, it was observed as under:

“105. We, therefore, reiterate that the power derived from the Penal Code for any modified punishment within the punishment provided for in the Penal Code for such specified offences can only be exercised by the High Court and in the event of further appeal only by the Supreme Court and not by any other court in this country. To put it differently, the power to impose a modified punishment providing for any specific term of incarceration or till the end of the convict’s life as an alternate to death penalty, can be exercised only by the High Court and the Supreme Court and not by any other inferior court.”

10.10 Consequently, the ratio laid down in Swamy Shraddananda (2) with regard to special category of sentence was affirmed. It was expressed that the opinion of this Court in Sangeet vs. State of Haryana, (2013) 2 SCC 452 that the deprival of remission power of the appropriate Government by awarding sentences of twenty or twenty-five years without any remission was not permissible, was not in consonance with law and hence, the said judgment was overruled.

11. Recently, this Court in Shiva Kumar vs. State of Karnataka, (2023) 9 SCC 817 (“Shiva Kumar”) reiterating the aforesaid observations made in Sriharan, observed that there is a power which can be derived from the IPC to impose a fixed term sentence or modified punishment which can only be exercised by the High Court or in the event of any further appeal, by the Supreme Court and not by any other Court. It was further observed that the Constitution Bench in Sriharan held that power to impose a modified punishment of providing any specific term of incarceration or till the end of convict’s life as an alternative to death penalty, can be exercised only by the High Court and the Supreme Court and not by any other inferior Court. More pertinently, it was observed that the observations of the Constitution Bench in Sriharan cannot be construed in a narrow perspective. Oka, J. speaking for the Bench observed that “the majority view in Sriharan cannot be construed to mean that such a power cannot be exercised by the Constitutional Courts unless the question is of commuting the death sentence”. For this, paragraph 104 of the judgment of the Constitution Bench in Sriharan was relied upon. Clarifying the position at paragraph 14 of the judgment in Shiva Kumar, Oka, J. held as under:

“14. Hence, we have no manner of doubt that even in a case where capital punishment is not imposed or is not proposed, the constitutional courts can always exercise the power of imposing a modified or fixed-term sentence by directing that a life sentence, as contemplated by “secondly” in Section 53IPC, shall be of a fixed period of more than fourteen years, for example, of twenty years, thirty years and so on. The fixed punishment cannot be for a period less than 14 years in view of the mandate of Section 433-A CrPC.”

(Underlining by us)

11.1 In the said case, the sentence imposed by the Fast Track Court (Sessions Court) on the appellant therein to undergo rigorous imprisonment for rest of his life for an offence punishable under Section 302 IPC was modified to the extent that the appellant was directed to undergo thirty years of actual sentence and to be released thereafter. The appeal was partly allowed to the above extent.

12. Navas alias Mulanavas was a criminal appeal which arose out of a death reference from the judgment of the Additional Sessions Judge, Fast Track Court, Thrissur in Sessions Case No.491 of 2006. The High Court had modified the death penalty to imprisonment for life with the further direction that the accused shall not be released from prison for a period of thirty years including the period already undergone with set off under Section 428 of Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (for short, “CrPC”) alone. The accused approached this Court assailing the aforesaid judgments both on conviction as well as on sentence. While considering the alternative submission regarding the sentence of imprisonment for thirty years without remission being excessive and disproportionate, this Court speaking through one of us (Viswanathan, J.) considered the judgments discussed above and after a chronological survey of a large number of cases, observed in paragraph 59 as under:

“59. A journey through the cases set out hereinabove shows that the fundamental underpinning is the principle of proportionality. The aggravating and mitigating circumstances which the Court considers while deciding commutation of penalty from death to life imprisonment, have a large bearing in deciding the number of years of compulsory imprisonment without remission, too. As a judicially trained mind pores and ponders over the aggravating and mitigating circumstances and in cases where they decide to commute the death penalty they would by then have a reasonable idea as to what would be the appropriate period of sentence to be imposed under the Swamy Shraddananda (supra) principle too. Matters are not cut and dried and nicely weighed here to formulate a uniform principle. That is where the experience of the judicially trained mind comes in as pointed out in V. Sriharan (supra). Illustratively in the process of arriving at the number of years as the most appropriate for the case at hand, which the convict will have to undergo before which the remission powers could be invoked, some of the relevant factors that the courts bear in mind are : – (a) the number of deceased who are victims of that crime and their age and gender; (b) the nature of injuries including sexual assault if any; (c) the motive for which the offence was committed; (d) whether the offence was committed when the convict was on bail in another case; (e) the premeditated nature of the offence; (f) the relationship between the offender and the victim; (g) the abuse of trust if any; (h) the criminal antecedents; and whether the convict, if released, would be a menace to the society. Some of the positive factors have been, (1) age of the convict; (2) the probability of reformation of convict; (3) the convict not being a professional killer; (4) the socioeconomic condition of the accused; (5) the composition of the family of the accused and (6) conduct expressing remorse. These were some of the relevant factors that were kept in mind in the cases noticed above while weighing the pros and cons of the matter. The Court would be additionally justified in considering the conduct of the convict in jail; and the period already undergone to arrive at the number of years which the Court feels the convict should, serve as part of the sentence of life imprisonment and before which he cannot apply for remission. These are not meant to be exhaustive but illustrative and each case would depend on the facts and circumstances therein.”

12.1 Applying the aforesaid factors to the case, this Court allowed the appeal in part by modifying the sentence imposed under Section 302 IPC by the High Court for a period of thirty years’ of life imprisonment without remission to a period of twenty- five years without remission, including the period already undergone.

13. We have discussed the implications of the punishment imposed on the appellant herein by analysing the same and holding that the life imprisonment has been fixed at twenty years of actual imprisonment without consideration of remission. This means that within the twenty years of sentence the appellant could not have sought any remission of his sentence. Therefore, it was mandatory on the part of the appellant to have completed twenty years of actual imprisonment without remission and pay fine of Rs.10,000/- (Rupees ten thousand). This sentence imposed by the High Court was affirmed by this Court except for the singular modification already noted. Then, what would be the position after completion of twenty years of actual imprisonment? Does it mean that after the completion of twenty years of actual imprisonment the appellant has to seek remission of his sentence inasmuch as he has been awarded a life imprisonment or, on the other hand, on completion of twenty years of actual imprisonment without remission the appellant can be released from prison.

14. The expression “remission” has been considered in a number of judgments which we can discuss. This is as opposed to the expression “parole and furlough” etc. With reference to the decisions of this Court and on a discussion of the expression “remission”, it becomes clear that the said expression is used in two nuances: firstly, when the remission of sentence would mean a reduction in the sentence imposed on a convict without wiping out of the conviction which does not amount to an acquittal. On the other hand, remissions are also granted during the course of undergoing a sentence on the basis of the certain legal considerations. The same can be discussed in detail.

14.1 The principles covering grant of remission as distinguished from concepts such as “commutation”, “pardon”, and “reprieve” can be brought out with reference to a judgment of this Court in State (NCT of Delhi) vs. Prem Raj, (2003) 7 SCC 121 (“Prem Raj”). Articles 72 and 161 deal with clemency powers of the President of India and the Governor of a State respectively, and also include the power to grant pardons, reprieves, respites or remissions of punishment or to suspend, remit or commute the sentences in certain cases. The power under Article 72, inter alia, extends to all cases where the punishment or sentence is for an offence against any law relating to a matter to which the executive power of the Union extends and in all cases where the sentence is a sentence of death. Article 161 states that the Governor of a State shall have the power to grant pardons, reprieves, respites or remissions of punishment or to suspend, remit or commute the sentence of any person convicted of any offence against any law relating to a matter to which the executive power of the State extends. It was observed in the said judgment that the powers under Articles 72 and 161 of the Constitution of India are absolute and cannot be fettered by any statutory provision, such as, Sections 432, 433 or 433-A of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (hereinafter, “CrPC”) or by any prison rules.

14.1.1 It was further observed in Prem Raj that a pardon is an act of grace, proceeding from the power entrusted with the execution of the laws, which exempts the individual on whom it is bestowed from the punishment the law inflicts for a crime he has committed. It affects both the punishment prescribed for the offence and the guilt of the offender. But pardon has to be distinguished from “amnesty” which is defined as a “general pardon of political prisoners; an act of oblivion”. An amnesty would result in the release of the convict but does not affect disqualification incurred, if any. “Reprieve” means a stay of execution of a sentence, a postponement of a capital sentence. “Respite” means awarding a lesser sentence instead of the penalty prescribed in view of the fact that the accused has had no previous conviction. It is tantamount to a release on probation for good conduct under Section 360 of the CrPC. On the other hand, remission is reduction of a sentence without changing its character. In the case of a remission, neither the guilt of the offender is affected nor is the sentence of the court, except in the sense that the person concerned does not suffer incarceration for the entire period of the sentence, but is relieved from serving out a part of it. Commutation is change of a sentence to a lighter sentence of a different kind. Section 432 of the CrPC empowers the appropriate Government to suspend or remit sentences.

14.2 Further, a remission of sentence does not mean acquittal and an aggrieved party still has every right to vindicate himself or herself. In this context, reliance could be placed on Sarat Chandra Rabha vs. Khagendranath Nath, AIR 1961 SC 334, wherein a Constitution Bench of this Court, while distinguishing between a pardon and a remission, observed that an order of remission does not wipe out the offence and it also does not wipe out the conviction. All that it does is to have an effect on the execution of the sentence; though ordinarily a convicted person would have to serve out the full sentence imposed by a court, he need not do so with respect to that part of the sentence which has been ordered to be remitted. An order of remission, thus, does not in any way interfere with the order of the court; it affects only the execution of the sentence passed by the court and frees the convicted person from his liability to undergo the full term of imprisonment inflicted by the court even though the order of conviction and sentence passed by the court still stands as it is. The power to grant remission is an executive power and cannot have the effect which the order of an appellate or revisional court would have of reducing the sentence passed by the trial court and substituting in its place the reduced sentence adjudged by the appellate or revisional court. According to Weater’s Constitutional Law, to cut short a sentence by an act of clemency is an exercise of executive power which abridges the enforcement of the judgment but does not alter it qua the judgment.

14.3 Reliance could be placed on State of Haryana vs. Mahender Singh, (2007) 13 SCC 606, to observe that a right to be considered for remission, keeping in view the constitutional safeguards of a convict under Articles 20 and 21 of the Constitution of India, must be held to be a legal one. Such a legal right emanates from not only the Prisons Act, 1894 but also from the Rules framed thereunder. Although no convict can be said to have any constitutional right for obtaining remission in his sentence (except under Articles 72 and 161), the policy decision itself must be held to have conferred a right to be considered therefor. Whether by reason of a statutory rule or otherwise, if a policy decision has been laid down, the persons who come within the purview thereof are entitled to be treated equally – vide State of Mysore vs. H. Srinivasmurthy, (1976) 1 SCC 817.

14.4 Satish vs. State of U.P., (2021) 14 SCC 580 can be pressed into service to hold that the length of the sentence or the gravity of the original crime cannot be the sole basis for refusing premature release. Any assessment regarding a predilection to commit crime upon release must be based on antecedents as well as conduct of the prisoner while in jail, and not merely on his age or apprehensions of the victims and witnesses. It was observed that although a convict cannot claim remission as a matter of right, once a law has been made by the appropriate legislature, it is not open for the executive authorities to surreptitiously subvert its mandate. It was further observed that where the authorities are found to have failed to discharge their statutory obligations despite judicial directions, it would then not be inappropriate for a Constitutional Court while exercising its powers of judicial review to assume such task onto itself and direct compliance through a writ of mandamus. Considering that the petitioners therein had served nearly two decades of incarceration and had thus suffered the consequences of their actions, a balance between individual and societal welfare was struck by granting the petitioners therein conditional premature release, subject to their continuing good conduct. In the said case, a direction was issued to the State Government to release the prisoners therein on probation in terms of Section 2 of the U.P. Prisoners Release on Probation Act, 1938 within a period of two weeks. Liberty was reserved to the respondent State with the overriding condition that the said direction could be reversed or recalled in favour of any party or as per the petitioner therein.

14.5 The following judgments of this Court are apposite to the concept of remission:

14.5.1 In Maru Ram, a Constitution Bench considered the validity of Section 433-A of the CrPC. Krishna Iyer, J. speaking for the Bench, observed: (SCC p. 129, para 25)

“25. … Ordinarily, where a sentence is for a definite term, the calculus of remissions may benefit the prisoner to instant release at the point where the subtraction results in zero.”

14.5.2 However, when it comes to life imprisonment, where the sentence is indeterminate and of an uncertain duration, the result of subtraction from an uncertain quantity is still an uncertain quantity and release of the prisoner cannot follow except on some fiction of quantification of a sentence of uncertain duration.

14.5.3 Referring to Gopal Vinayak Godse, it was observed that the said judgment is an authority for the proposition that a sentence of imprisonment for life is one of “imprisonment for the whole of the remaining period of the convicted person’s natural life”, unless the said sentence is commuted or remitted by an appropriate authority under the relevant provisions of law. In the aforesaid case, a distinction was drawn between remission in sentence and life sentence. Remission, limited in time, helps computation but does not ipso jure operate as release of the prisoner. But, when the sentence awarded by the Judge is for a fixed term, the effect of remissions may be to scale down the term to be endured and reduce it to nil, while leaving the factum and quantum of sentence intact. However, when the sentence is a life sentence, remissions, quantified in time, cannot reach a point of zero. Since Section 433-A deals only with life sentences, remissions cannot entitle a prisoner to release. It was further observed that remission, in the case of life imprisonment, ripens into a reduction of sentence of the entire balance only when a final release order is made. If this is not done, the prisoner will continue to be in custody. The reason is that life sentence is nothing less than lifelong imprisonment and remission vests no right to release when the sentence is of life imprisonment nor is any vested right to remission cancelled by compulsory fourteen years jail life as a life sentence is a sentence for whole life.

14.5.4 Interpreting Section 433-A, it was observed that it was a savings clause in which there are three components. Firstly, CrPC generally governs matters covered by it. Secondly, if a special or local law exists covering the same area, the latter law will be saved and will prevail, such as short sentencing measures and remission schemes promulgated by various States. The third component is that if there is a specific provision to the contrary, then it would override the special or local law. It was held that Section 433-A of the CrPC picks out of a mass of imprisonment cases, a specific class of life imprisonment cases and subjects it explicitly to a particularised treatment. Therefore, Section 433-A of the CrPC applies in preference to any special or local law. This is because, Section 5 of the CrPC expressly declares that specific provision, if any, to the contrary will prevail over any special or local law. Therefore, Section 433-A of the CrPC would prevail and escape exclusion of Section 5 thereof. The Constitution Bench concluded that Section 433-A of the CrPC is supreme over the remission rules and short-sentencing statutes made by various States. Section 433-A of the CrPC does not permit parole or other related release within a span of fourteen years.

14.5.5 It was further observed that criminology must include victimology as a major component of its concerns. When a murder or other grievous offence is committed, the victims or other aggrieved persons must receive reparation and social responsibility of the criminal to restore the loss or heal the injury is part of the punitive exercise although the length of the prison term is no reparation to the crippled or bereaved.

14.5.6 Fazal Ali, J. in his concurring judgment in Maru Ram observed that crime is rightly described as an act of warfare against the community touching new depths of lawlessness. According to him, the object of imposing a deterrent sentence is threefold. While holding that a deterrent form of punishment may not be the most suitable or ideal form of punishment, yet, the fact remains that a deterrent punishment prevents occurrence of offence. He further observed that Section 433-A of the CrPC is actually a piece of social legislation which by one stroke seeks to prevent dangerous criminals from repeating offences and on the other hand, protects the society from harm and distress caused to innocent persons. Therefore, he opined that where Section 433-A applies, no question of reduction of sentence arises at all unless the President of India or the Governor of a State choose to exercise their wide powers under Article 72 or Article 161 of the Constitution respectively, which also have to be exercised according to sound legal principles as any reduction or modification in the deterrent punishment would, far from reforming the criminal, be counterproductive.

14.6 State of Haryana vs. Mohinder Singh, (2000) 3 SCC 394 is a case which arose under Section 432 of the CrPC on remission of sentence in which the difference between the terms “bail”, “furlough” and “parole” having different connotations were discussed. It was observed that furloughs are variously known as temporary leaves, home visits or temporary community release and are usually granted when a convict is suddenly faced with a severe family crisis such as death or grave illness in the immediate family and often the convict/inmate is accompanied by an officer as part of the terms of temporary release of special leave. Parole is the release of a prisoner temporarily for a special purpose or completely before the expiry of the sentence, on promise of good behaviour. Conditional release from imprisonment is to entitle a convict to serve remainder of his term outside the confines of an institution on his satisfactorily complying all terms and conditions provided in the parole order.

14.7 In Poonam Lata vs. M.L. Wadhawan, (1987) 3 SCC 347, it was observed that parole is a provisional release from confinement but it is deemed to be part of imprisonment. Release on parole is a wing of reformative process and is expected to provide opportunity to the prisoner to transform himself into a useful citizen. Parole is thus, a grant of partial liberty or lessening of restrictions on a convict prisoner but release on parole does not change the status of the prisoner. When a prisoner is undergoing sentence and confined in jail or is on parole or furlough, his position is not similar to a convict who is on bail. This is because a convict on bail is not entitled to the benefit of the remission system. In other words, a prisoner is not eligible for remission of sentence during the period he is on bail or when his sentence is temporarily suspended. Therefore, such a prisoner who is on bail is not entitled to get remission earned during the period he is on bail.

15. The sentence imposed on the appellant herein, inter alia, is recapitulated as under:

“Life imprisonment which shall be 20 years of actual imprisonment without consideration of remission, and fine of Rs.10,000/-.”

The word “which” used after the words “life imprisonment”, is an interrogative pronoun, related pronoun and determiner, referring to something previously mentioned when introducing a clause giving further information. Therefore, the sentence of life imprisonment is determined as twenty years which is of actual imprisonment. Further, during the period of twenty years, the appellant cannot seek remission during his sentence of twenty years of imprisonment i.e., after completion of fourteen years as per Section 433A of the CrPC but must continue his sentence for a period of twenty years without any remission whatsoever. Therefore, the appellant has no right to make any application for remission of the above sentence for a period of twenty years.

15.1 In Criminal Appeal Nos.1531-1533 of 2015 filed by Vikas Yadav as well as in Criminal Appeal Nos.1528-1530 of 2015 which also included the appeal filed by the appellant herein, the imposition of a fixed term sentence on the appellants by the High Court was also questioned but this Court observed that such a term of sentence on the appellants by the High Court could not be found fault with. Placing reliance on Gopal Singh vs. State of Uttarakhand, (2013) 7 SCC 545, at paragraph 84 of its judgment in the aforesaid criminal appeal, this Court observed that “Judged on the aforesaid parameters, we reiterate that the imposition of fixed terms sentence is justified.”

15.2 In the instant case, as already noted, the life imprisonment being twenty years of actual imprisonment was without consideration of remission. Soon after the period of twenty years is completed, in our view, the appellant has to be simply released from jail provided the other sentences run concurrently. The appellant is not under an obligation to make an application seeking remission of his sentence on completion of twenty years. This is simply for the reason that the appellant has completed his twenty years of actual imprisonment and in fact, during the period of twenty years, the appellant was not entitled to any remission. Thus, in the instant case, on completion of the twenty years’ of actual imprisonment, it is wholly unnecessary for the appellant to seek remission of his sentence on the premise that his sentence is a life imprisonment i.e. till the end of his natural life. On the other hand, learned senior counsel appearing for the respondent-State and respondent-complainant contended that once the period of twenty years is over, which was without any consideration of remission, the appellant had to seek remission of his sentence (life imprisonment) by making an application to the Sentence Review Board which would consider in accordance with the applicable policy and decide whether the remission of sentence imposed on the appellant has to be granted or not. Such a contention cannot be accepted for the following reasons:

(i) firstly, because, in the instant case, the sentence of life imprisonment has been fixed to be twenty years of actual imprisonment which the appellant herein has completed;

(ii) secondly, during the period of twenty years the appellant was not entitled to seek any remission; and

(iii) thirdly, on completion of twenty years of actual imprisonment, the appellant is entitled to be released.

15.3 This is because in this case, instead of granting death penalty, alternative penalty of life imprisonment has been awarded which shall be for a period of twenty years of actual imprisonment. That even in the absence of death penalty being imposed, life imprisonment of a fixed term of twenty years was imposed which is possible only for a High Court or this Court to do so. The period of twenty years is without remission inasmuch as the appellant is denied the right of remission of his sentence on completion of fourteen years as per Section 432 read with Section 433-A of the CrPC. Such a right has been denied by the High Court but that does not mean that on completion of twenty years of imprisonment the appellant has to still seek reduction of his sentence on the premise that he was awarded life imprisonment which is till the end of his natural life. If that was so, the High Court would have specified it in those terms. On the other hand, the High Court has imposed life imprisonment which shall be twenty years of actual imprisonment without consideration of remission. The High Court was of the view that for a period of twenty years, the appellant has to undergo actual imprisonment which would not take within its meaning any period granted for parole or furlough.

15.4 In the instant case, the actual imprisonment of twenty years was admittedly completed by the appellant on 09.03.2025 which was without any remission. If that is so, it would imply that the appellant has completed his period of sentence. In fact, the award of the aforesaid sentence was also confirmed by this Court. On completion of twenty years of actual imprisonment on 09.03.2025, the appellant was entitled to be released. The release of the appellant from jail does not depend upon further consideration as to whether he has to be released or not and as to whether remission has to be granted to him or not by the Sentence Review Board. In fact, the Sentence Review Board cannot sit in judgment over what has been judicially determined as the sentence by the High Court which has been affirmed by this Court. There cannot be any further incarceration of the appellant herein from 09.03.2025 onwards. On the other hand, in the instant case, the appellant’s prayer for furlough was refused by the High Court and, thereafter, this Court granted furlough only on 25.06.2025 as he had completed his actual sentence by then, pending consideration of the amended prayer made by the appellant herein on completion of his sentence on 09.03.2025. Therefore, the continuous incarceration of the appellant from 09.03.2025 onwards was illegal. In fact, on 10.03.2025, the appellant ought to have been released from prison as he had completed the sentence imposed on him by the High Court as affirmed by this Court.

15.5 In Bhola Kumar vs. State of Chhattisgarh, 2022 SCC OnLine SC 837, this Court lamented the unfortunate fate of prisoners languishing behind bars even long after completing their period of sentence noted as follows:

“23. …When such a convict is detained beyond the actual release date it would be imprisonment or detention sans sanction of law and would thus, violate not only Article 19(d) but also Article 21 of the Constitution of India. …”

15.6 Although, presently the appellant is not in custody but on furlough for three months pursuant to the interim order dated 25.06.2025 passed by this Court, he need not surrender after expiry of the period of furlough as he has completed his jail sentence of twenty years on 09.03.2025, if not wanted in any other case.

15.7 Consequently, we hold that in all cases where an accused/convict has completed his period of jail term, he shall be entitled to be released forthwith and not continued in imprisonment if not wanted in any other case. We say so in light of Article 21 of the Constitution of India which states that no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.

16. A copy of this order shall be circulated by the Registry of this Court to all the Home Secretaries of the States/Union Territories to ascertain whether any accused/convict has remained in jail beyond the period of sentence and if so, to issue directions for release of such accused/convicts, if not wanted in any other case. Similarly, a copy of this order shall also be sent by the Registry of this Court to the Member Secretary, National Legal Services Authority for onward transmission to all Member Secretaries of the States/Union Territories Legal Services Authorities for communication to all the Member Secretaries of the District Legal Services Authorities in the States for the purpose of implementation of this judgment.

This appeal is disposed of in the aforesaid terms.