Appreciation of Testimonial Evidence of Minor Victims

K.P. Kirankumar v State

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that in cases of child trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation, the evidence of minor victims must be appreciated with sensitivity and realism. It held that the credible testimony of a minor victim can, by itself, sustain a conviction and cannot be rejected on the basis of...

Case Details

Judgement Date: 19 December 2025

Citations: 2025 INSC 1473 | 2025 SCO.LR 12(4)[20]

Bench: Manoj Misra J, Joymalya Bagchi J

Keyphrases: child trafficking–commercial sexual exploitation–minor victim testimony–judicial appreciation of evidence–sensitivity and realism–victim not an accomplice–sole testimony sufficient for conviction–Sections 366A, 372, 373 IPC–Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956–Sections 3, 4, 5 and 6–Karnataka High Court judgment affirmed–appeal dismissed

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

Joymalya Bagchi, J.

1. Leave granted.

2. The instant case lays bare the deeply disturbing reality of child trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation in India, an offence that strikes at the very foundations of dignity, bodily integrity and the State’s constitutional promise of protection to every child against exploitation leading to moral and material abandonment. The facts before us are not isolated aberrations but form part of a wider and entrenched pattern of organised exploitation that continues to flourish despite legislative safeguards.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

3. On the fateful day of 22.11.2010, the complainant, H.Sidappa (PW-1) received information from NGO workers, Tojo and Dominic (PW-11) that minor girls were being kept for prostitution at a rented house in Peenya, T. Dasarahalli, Bangalore. After obtaining the requisite verbal permission from senior officers, he, along with the raiding party, proceeded to the spot. One Jaikar (PW- 8), an associate of PW-11 was sent to the premises as a decoy with Manjunath (PW-12). Jaikar offered money to the appellant (A1) for having sex with the minor victim (PW-13) who was in the house. After handing over the money, PW-8 intimated PW-1. Consequently, PW-1 along-with other officers and PW-11 rescued the minor victim. Upon search, the currency notes handed over to the appellant were recovered. A mobile phone and Rs. 620 were seized from the appellant’s wife (A2). A condom was also found on the cot. PW-1 lodged a written complaint bearing FIR No. 778/2010 at Peenya Police Station, Bangalore against A1 & A2 u/s. 366A, 372, 373 & 34 of the Indian Penal Code, 18601 r/w.s.3, 4, 5, 6 and 9 of the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 19562. Charge-sheet was filed u/s. 366A, 372, 373 & 34, IPC r/w. s. 3, 4,5 & 6, ITPA.

4. The case was registered as C.C. No. 5438/2011 and taken up for trial. Charges were framed under the aforesaid provisions. Prosecution proceeded to examine 16 prosecution witnesses, arrayed as PW-1 to PW-16, to prove its case.

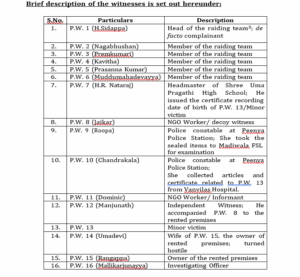

Brief description of the witnesses is set out hereunder:

FINDINGS RECORDED BY THE COURTS BELOW:

(i) Trial Court:

5. Trial Court placed substantial reliance upon the testimony of minor victim, PW-13, which stood amply corroborated by the testimonies of PW-8 and PW-12. The victim’s testimony revealed that four unknown individuals had forcibly removed her from the Chikkabanavara bus stand and placed her in the custody of A1 & A2 at a rented premises in Dasarahalli. She further stated that the appellant subsequently sent her to the house of one Naveen, where she was coerced into prostitution. Owing to her ensuing reluctance, she was taken back to the rented premises and forced to indulge in illicit sexual intercourse. A1 & A2 also wrongfully confined her within the rented premises and prevented her from establishing any contact with the outside world. Upon considering the witness testimonies, the Court observed that the ingredients of the charged offences stood proved, particularly in the absence of any credible evidence from the accused persons to demonstrate that they bore any relationship with the victim. Therefore, the Trial Court convicted A1 & A2 u/s. 366A, 373, 34 IPC r/w. s. 3, 4, 5 & 6 of the ITPA vide order dated 25.07.2013.

(ii) High Court:

6. Assailing the judgment passed by the Trial Court, Criminal Appeal No. 860/2013 was preferred by A1 & A2 before the High Court. The High Court, upon re-appreciation of the evidence on record, held that the ingredients of the alleged offences stood established. The defence failed to put forth any credible evidence while responding to the incriminatory circumstances proved by the prosecution. Consequently, High Court concluded that the prosecution had proved its case beyond reasonable doubt. Accordingly, the Criminal Appeal was dismissed vide order dated 05.02.2025. The Court further observed that no mitigating circumstances were forthcoming on record to warrant any reduction of sentence.

7. Aggrieved by the concurrent findings of the Trial Court and High Court, the appellant has preferred the present appeal.

ANALYSIS:

8. The prosecution case primarily hinges on the version of the victim (PW-13). Driven by abject poverty, the victim left her residence seeking respectful employment. Taking advantage of such economic vulnerability, four unknown persons brought her to the appellant’s house. In her presence, appellant made telephone calls for sexually exploiting the victim. Pursuant to such negotiation, some persons came to the house and the victim was asked to have sex with them, which she refused. Thereupon, A1 & A2 compelled her to accompany one Naveen, who took her to another place where she was sexually exploited. Thereafter, she was brought back to the appellant’s rented apartment where she had to satisfy the lust of various customers. Finally, on 22.11.2020, the police raided the apartment and rescued her. Her statement wasrecorded before the Magistrate which substantially corroborates her version in Court.

9. Ld. Counsel for appellant has challenged the victim’s version on various scores. He contends that the victim’s evidence regarding forcible sexual intercourse is an embellished one. While in Court the victim claimed that due to illicit sexual intercourse with two persons, she had suffered injuries and blood oozed out of her private parts, such fact does not transpire in her previous statement before the Magistrate. The topography of the rented apartment comprising two rooms, kitchen and a bathroom as narrated by the victim is not corroborated by PW-8 or PW-12 who claim that the apartment comprised a hall, kitchen and bathroom.

10. The Courts below rightly rebutted such contentions holding that the contradictions are minor and the victim’s version has been substantially corroborated by other evidence on record. We are of the view that both Trial Court and High Court have correctly appreciated the evidence of the minor trafficked victim, considering the need for sensitivity and latitude while appreciating the evidence of minor victims of sex trafficking and prostitution.

11. While appreciating the evidence of a minor victim of trafficking, the Court ought to bear in mind:

i. Her inherent socio-economic and, at times, cultural vulnerability when the minor belongs to a marginalised or socially and culturally backward community.

ii. Complex and layered structure of organised crime networks which operate at various levels of recruiting, transporting, harbouring and exploiting minor victims. Such organised crime activities operate as apparently independent verticals whose insidious intersections are conveniently veiled through subterfuges and deception to hoodwink innocent victims. Such diffused and apparently disjoint manner in which the crime verticals operate in areas of recruitment, transportation, harbouring and exploitation make it difficult, if not impossible for the victim, to narrate with precision and clarity the interplay of these processes as tentacles of an organised crime activity to which she falls prey. Given this situation, failure to promptly protest against ostensibly innocuous yet ominous agenda of the trafficker ought not to be treated as a ground to discard a victim’s version as improbable or against ordinary human conduct.

iii. Recounting and narration of the horrible spectre of sexual exploitation even before law enforcement agencies and the Court is an unpalatable experience leading to secondary victimisation. This is more acute when the victim is a minor and is faced with threats of criminal intimidation, fear of retaliation, social stigma and paucity of social and economic rehabilitation. In this backdrop, judicial appreciation of victim’s evidence must be marked by sensitivity and realism.

iv. If on such nuanced appreciation, the version of the victim appears to be credible and convincing, a conviction may be maintained on her sole testimony. A victim of sex trafficking, particularly a minor, is not an accomplice and her deposition is to be given due regard and credence as that of an injured witness. We draw inspiration from the poignant remarks in State of Punjab v. Gurmit Singh and Others ((State of Punjab v. Gurmit Singh and Others, (1996) 2 SCC 384)) a locus classicus in victimology and gender justice:-

“21. Of late, crime against women in general and rape in particular is on the increase. It is an irony that while we are celebrating woman’s rights in all spheres, we show little or no concern for her honour. It is a sad reflection on the attitude of indifference of the society towards the violation of human dignity of the victims of sex crimes. We must remember that a rapist not only violates the victim’s privacy and personal integrity, but inevitably causes serious psychological as well as physical harm in the process. Rape is not merely a physical assault — it is often destructive of the whole personality of the victim. A murderer destroys the physical body of his victim, a rapist degrades the very soul of the helpless female. The courts, therefore, shoulder a great responsibility while trying an accused on charges of rape. They must deal with such cases with utmost sensitivity. The courts should examine the broader probabilities of a case and not get swayed by minor contradictions or insignificant discrepancies in the statement of the prosecutrix, which are not of a fatal nature, to throw out an otherwise reliable prosecution case. If evidence of the prosecutrix inspires confidence, it must be relied upon without seeking corroboration of her statement in material particulars. If for some reason the court finds it difficult to place implicit reliance on her testimony, it may look for evidence which may lend assurance to her testimony, short of corroboration required in the case of an accomplice. The testimony of the prosecutrix must be appreciated in the background of the entire case and the trial court must be alive to its responsibility and be sensitive while dealing with cases involving sexual molestations.”

(Emphasis supplied)

12. Weighing PW-13’s version on the aforesaid legal scales, we are convinced that her testimony is most credible and establishes that A1 & A2 had procured her for sexual exploitation and utilised her for such immoral purposes. The minor’s version is also corroborated by other evidence on record. PW-11, an NGO worker had intimated the police with regard to prostitution being carried out by the appellant in his rented premises. In order to work out such information, PW-8, an associate of the NGO was sent as a decoy. PW-12 accompanied him. PW-8 found the minor in the premises and offered money to the appellant for sexual gratification. Thereafter, he intimated the police who subsequently raided the premises and rescued the minor. Police also recovered cash received by the appellant, along-with other incriminating articles namely, condom etc.

13. Defence sought to improbabilize the prosecution case on the following grounds. They contended that while PW-1 claimed hehad received a missed call from PW-8, PW -8 deposed that he had a conversation with PW-1 prior to the raid. This has been rightly rebutted by the courts below as a minor contradiction. Admittedly, there was some form of communication between PW-8 and PW-1 prior to the raid and as such, slight variation with regard to the manner in which such communication took place does not render the unfolding of the prosecution case vulnerable. The other aspect highlighted by the defence namely, failure on part of PW-12 to identify the accused in the court is also rendered inconsequential. PW-12 has otherwise substantially corroborated the prosecution case and explained away such lapse of memory due to passage of time. Admittedly, A1 & A2 were apprehended from the spot along- with the minor victim clearly dispelling any shadow of doubt with regard to their presence at the spot. The fact that A1 & A2 had taken the premises on rent is also proved through the house- owner PW-15’s testimony. The apparent variation in the topography of the rented apartment i.e. whether there were two rooms or one is also of no consequence. The decoy, PW-8 clearly proves that appellant had received money in lieu of permitting him to engage in sexual intercourse with PW-13 in the said apartment. His version is corroborated by an independent witness, PW-12. Cash and other incriminating articles i.e. condom were recovered from the spot as per panchnama Ex. P-2. The evidence on recordclearly proves beyond doubt that A1 & A2 were using the premises for prostitution by sexually exploiting the minor victim, PW-13, for commercial purposes, and thereby committed offences u/s. 3, 4, 5 and 6 of the ITPA in addition to the offences under the Penal Code.

14. Age of the victim on the date of the incident has been proved as 16 years and 6 months. The letter Ex. P-3 issued by the School Headmaster (P.W. 7) records her date of birth as 24.04.1994. The submission of the appellant that such evidence is unreliable as no ossification test was conducted does not hold water. Age determined through ossification test is a mere approximation and cannot be held to have better probative value than a certificate issued by the school. In Jarnail Singh v. State of Haryana ((Jarnail Singh v. State of Haryana, (2013) 7 SCC 263)), this Court held that determination of age of a minor victim of sexual offence is to be done with reference to Rule 12 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Rules, 2007 wherein the date of birth recorded in the certificate from the school first attended by the victim would take precedence over medical opinioni.e. ossification test. The Court held as follows:

“23. Even though Rule 12 is strictly applicable only to determine the age of a child in conflict with law, we are of the view that the aforesaid statutory provision should be the basis for determining age, even of a child who is a victim of crime. For, in our view, there is hardly any difference insofar as the issue of minority is concerned, between a child in conflict with law, and a child who is a victim of crime. Therefore, in our considered opinion, it would be just and appropriate to apply Rule 12 of the 2007 Rules, to determine the age of the prosecutrix VW, PW 6. The manner of determining age conclusively has been expressed in sub-rule (3) of Rule 12 extracted above. Under the aforesaid provision, the age of a child is ascertained by adopting the first available basis out of a number of options postulated in Rule 12(3). If, in the scheme of options under Rule 12(3), an option is expressed in a preceding clause, it has overriding effect over an option expressed in a subsequent clause. The highest rated option available would conclusively determine the age of a minor. In the scheme of Rule 12(3), matriculation (or equivalent) certificate of the child concerned is the highest rated option. In case, the said certificate is available, no other evidence can be relied upon. Only in the absence of the said certificate, Rule 12(3) envisages consideration of the date of birth entered in the school first attended by the child. In case such an entry of date of birth is available, the date of birth depicted therein is liable to be treated as final and conclusive, and no other material is to be relied upon. Only in the absence of such entry, Rule 12(3) postulates reliance on a birth certificate issued by a corporation or a municipal authority or a panchayat. Yet again, if such a certificate is available, then no other material whatsoever is to be taken into consideration for determining the age of the child concerned, as the said certificate would conclusively determine the age of the child. It is only in the absence of any of the aforesaid, that Rule 12(3) postulates the determination of age of the child concerned, on the basis of medical opinion.”

15. Finally, it is argued that the prosecution, under the special law, must fail as the search and recovery of the minor was conducted in violation of s. 15(2) of the ITPA. S.15(2) reads as follows:

“15. Search without warrant.(2) Before making a search under sub-section (1), the special police officer [or the trafficking police officer, as the case may be] shall call upon two or more respectable inhabitants (at least one of whom shall be a woman) of the locality in which the place to be searched is situate, to attend and witness the search, and may issue an order in writing to them or any of them so to do:[Provided that the requirement as to the respectable inhabitants being from the locality in which the place to be searched is situate shall not apply to a woman required to attend and witness the search.]”

16. The aforesaid provision enjoins that, at the time of search under the special law, the police officer shall call upon two or more respectable inhabitants of the locality, including a woman (who may not be a member of the locality) to attend and witness the search and may issue an order in writing to such persons to do so. The provision is akin to S.100 (4) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 19733 which requires search to be conducted in presence of two or more respectable members of the locality. S. 15(2) fell for interpretation in Bai Radha v. State of Gujarat4 wherein distinguishing the ratio in State (UT of Delhi) v. Ram Singh5 (where search was conducted by an authorised police officer), this Court held that infraction of such provision is an irregularity and does not per se vitiate the trial unless it is shown that there has been a failure of justice.

“6. … This case6 (( certainly supports one part of the submission of the counsel for the appellant that the Act is a complete Code with respect to what has to be done under it. In that sense it would be legitimate to say that a search which is to be conducted under the Act must comply with the provisions contained in Section 15; but it cannot be held that if a search is not carried out strictly in accordance with the provisions of that section, the trial is rendered illegal. There is hardly any parallel between an officer conducting a search who has no authority under and a search having been made which does not strictly conform to the provisions of Section 15 of the Act. The principles which have been settled with regard to the effect of an irregular search made in exercise of the powers under Section 165 of the Code of Criminal Procedure would be fully applicable even to a case under the Act, where the search has not been made in strict compliance with its provisions. It is significant that there is no provision in the Act according to which any search carried out in contravention of Section 15 would render the trial illegal. In the absence of such a provision we must apply the law which has been laid down with regard to searches made under the provision of the Criminal Procedure Code.”

17. In the present case, the search was undertaken in presence of the decoy PW-8 and PW-12. They are respectable and independent persons residing in the same city, who had joined the search. Nothing is brought on record to show that they are pocket witnesses who had deposed for the police in other cases. It is also relevant to note that PW-14 (wife of the owner of the premises) had also been requested to witness the search. Unfortunately, she turned hostile and denied having made any previous statement to the police, but during cross-examination, the prosecution confronted her with her earlier statement, wherein it is noted that she had requested the police to undertake the search.

18. In this factual background, we are of the view that statutory requirements u/s. 15(2) were substantially complied with and the conviction cannot be doubted on such score.

19. Therefore, we uphold the conviction and sentence awarded by the High Court and dismiss the appeal. Pending application(s), if any, shall stand disposed of.