Right of Legal Heirs to Continue Appeal

Khem Singh (D) Through LRs v State Of Uttranchal

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that an aggrieved party’s right to appeal can be carried forward by their legal heirs.

A Sessions Court in Haridwar had convicted three persons, accused of murder and causing injury during a dispute. The High Court acquitted three accused who were sentenced to life imprisonment....

Case Details

Judgement Date: 31 July 2025

Citations: 2025 INSC 1024 | 2025 SCO.LR 8(4)[16]

Bench: B.V. Nagarathna J, K.V. Viswanathan J

Keyphrases: Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973—Section 372—right to prosecute—right to prefer an appeal includes legal heirs—substitution allowed

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

NAGARATHNA J.

1. Being aggrieved by the common judgment dated 12.09.2012 passed in Criminal Appeal Nos. 254 of 2004, 258 of 2004, 259 of 2004 by the High Court of Uttarakhand at Nainital, the original appellant Khem Singh S/o Tarachand preferred these Special Leave Petitions before this Court. By order dated 06.07.2017, leave was granted by this Court and consequently, the Special Leave Petitions have been converted to these Criminal Appeals.

Facts in Brief:

2. For ease of reference, the private respondents herein, namely, (i)Anil @ Neelu; ii) Pramod; and iii) Ashok, who were accused Nos. 4, 3, and 2 respectively in S.T. No.133/1993 in the Court of Addl. District & Sessions Judge, Haridwar (henceforth “Sessions Court”), are henceforth referred to as ‘respondents-accused’. The other accused in S.T. No.133/1993, who were acquitted by the Sessions Court, are referred to as ‘other accused’.

2.1 Briefly stated, the facts of the case according to the prosecution are that there was a long-standing previous enmity between the respondents-accused and other accused and the original informant and others. On 08.12.1992, there was some heated exchange between them. The next day, i.e. on 09.12.1992, at about 08.00 A.M., informant Tara Chand (P.W.1), his brother Virendra Singh, and W.1’s son Khem Singh (P.W.3) were attacked by the respondents-accused and the other accused using guns, sharp weapons, and bricks. As a result, Virendra Singh passed away, and P.W.1 and P.W.3 sustained injuries. On the arrival of villagers, all the accused managed to escape.

2.2 The specific roles attributed to the respondents-accused are that: i) Accused 2, Ashok, fired on Virendra Singh using a gun; (ii) Accused No.3, Pramod, fired on P.W.3 using a gun; and iii) Accused No.4, Anil @ Neelu, fired on Smt. Mithilesh, wife of P.W.3. On a complaint given by W.1 Tara Chand, Case Crime No.547/92 dated 09.12.1992 was registered at P.S. Jwalapur, District Haridwar against all the accused persons. The respondents- accused were charged under Sections 148, 452, 302, 307, 149, 326, and 149 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (hereinafter, “IPC”).

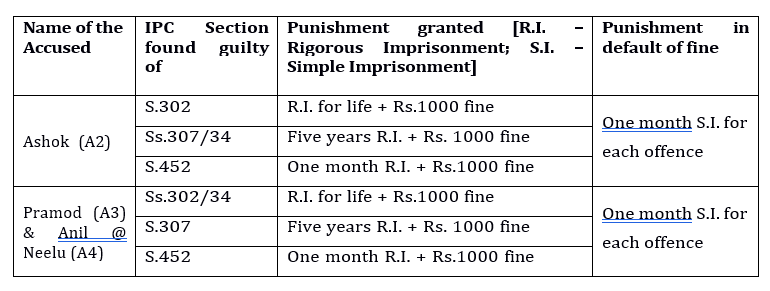

2.3 After examining all the material witnesses and after hearing both the parties, the Sessions Court, vide judgment and order dated 02.08.2004/04.08.2004 acquitted the other accused on the ground that the role assigned to them was not fully proved. However, the Sessions Court found that the case against the respondents-accused was fully proved beyond all reasonable The sentence passed against the respondents-accused is as follows:

2.4 Being aggrieved by the judgment and order of the Sessions Court, the respondents-accused preferred Criminal Appeal Nos.254, 258 and 259 of 2004 before the High Court of Uttarakhand at Nainital. The High Court, vide common impugned judgment and order dated 12.09.2012, allowed the criminal appeals filed by the respondents-accused.

2.5 The second respondent in Criminal Appeal 1330 of 2017 was appellant/Accused No.4-Anil @ Neelu in Criminal Appeal No.254 of 2004 before the High Court. The second respondent in Criminal Appeal No.1331 of 2017 was appellant/accused No.3- Pramod in Criminal Appeal No.258 of 2004 before the High Court. The second respondent in Criminal Appeal No.1332 of 2017 was appellant/accused No.2-Kali Ram in Criminal No.259 of 2004 before the High Court. For ease of reference, henceforth the second respondent in these appeals, who are accused Nos.4, 3 and 2 respectively, are referred to as accused in these appeals. The State’s Appeal No.47 of 2008 was also disposed of by the High Court along with the aforesaid appeals.

INTERLOCUTORY APPLICATION NOS.11322/2025, 11329/2025 & 131604 OF 2025 IN CRIMINAL APPEAL NOS.1330-1332 OF 2017:

2.6 During the pendency of these appeals, son of original appellant-Khem Singh (since deceased) – Raj Kumar filed an application seeking setting aside of the abatement and for substitution. Consequently, IA No.11322/2025 (application for seeking setting aside of the abatement), IA No.11329/2025 (application seeking condonation of delay in filing application for setting aside of abatement), and IA No.131604/2024 (application for substitution) have been preferred.

Submissions:

3. Learned counsel for the applicant contended that having regard to the proviso to Section 372 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (for short, “CrPC”), the substitution applications may be allowed by condoning the delay in filing the said application. He further contended that the original appellant was aggrieved by the acquittal of accused Nos.4, 3 and 2 respectively by the High Court when, in fact, they had been convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment and fine by the Sessions Court and hence, the original appellant herein preferred these appeals.

3.1 It was also brought to our notice that these appeals assume significance due to the fact that the State has not preferred any appeal as against the judgment and order of acquittal passed by the High Court by way of the impugned judgment and In the circumstances, in view of the proviso to Section 372 CrPC as well as the definition of ‘Victim’ laid down under Section 2(wa) of CrPC as well as the principles adumbrated by the Constitution Bench of this Court in PSR Sadhanantham vs. Arunachalam (1980) 3 SCC 141 (“PSR Sadhanantham”), the substitution applications may be allowed; the abatement may be set aside; the delay in filing the applications for seeking setting aside of the abatement may be condoned and the applicant may be substituted in place of the original appellant and the appeals may be heard on merits.

3.2 In this regard, learned counsel for the applicant also submitted that the proviso to Section 372 CrPC which has the expression ‘the right to prefer an appeal’ would also include ‘the right to prosecute an appeal’. In the circumstances, the right to prosecute an appeal given to a legal heir of the victim must also be construed to extend to a case where the legal heir of the original appellant, who was also an injured victim in the instant case must be brought on record. Moreover, the applicant is also an injured victim. It was contended that the delay in filing the applications for setting aside of the abatement and in filing the application for substitution was owing to the long pendency of these appeals before this Court as well as due to bona fide reasons. In this regard, learned counsel for the applicant submitted that the reason as to why the applications have to be allowed in these cases is also owing to the fact that the High Court, by the impugned judgment, which is a cryptic one as is evident by the manner in which the same has been written, has allowed the appeals filed by the accused and consequently acquitted them. In the circumstances, the applications may be allowed and in the place of the original appellant, who is since deceased, the applicant, his son, who is also an injured victim may be substituted so as to prosecute these appeals.

3.3 Per contra, learned senior counsel and learned counsel for the respondent(s) vehemently objected to the applications being allowed. In this regard, they drew our attention to Section 394 CrPC and contended that although the said provision refers to an appeal filed against a conviction, sub-section (1) of Section 394 CrPC deals with abatement of an appeal on the death of an accused when the appeal was filed under Sections 377 or 378 CrPC. The expression, “every other appeal under this Chapter” in sub-section (2) of Section 394 CrPC is significant inasmuch as the said sub- section lays down that apart from an appeal filed under Section 377 or Section 378 CrPC, every other appeal under the Chapter shall finally abate on the death of the appellant; that the CrPC has not defined the expression “appellant”, and it could be either a victim or a complainant, who is the appellant, or it could also be the convict or the accused who is an appellant; that the proviso expressly deals with a case where the accused or the convict is the appellant and if he dies during the pendency of the appeal, the legal heirs of such an accused can be brought on record to continue the appeal and they can seek an acquittal if the appeal had been filed under Section 377 or Section 378 CrPC or on any other ground. However, the said proviso does not extend to a case where an appeal is filed by a victim or a legal heir of a victim under the proviso to Section 372 CrPC. It was further submitted that the expression ‘near relative’ in the proviso to sub-section (2) of Section 394 CrPC is of a wider connotation to include a parent, spouse, lineal descendant, brother or sister, but such an expression cannot be applied in the case of substitution of an original victim who had preferred an appeal on his demise during the pendency of his appeal.

3.4 In the above circumstances, they contended that the applications may be Consequently, the appeal may also be dismissed as having abated since the original appellant has died during the pendency of the appeals before this Court.

Points for Consideration:

4. Having heard learned counsel for the parties, the following points arise for our consideration:

(a) Whether the applicant is entitled to be substituted in place of the original appellant so as to continue to prosecute these appeals?

(b) What order?

5. We have considered the arguments advanced at the bar in light of the provisions of the CrPC. It is noted that while Sections 377 and 378 CrPC were on the statute book even at the time of the enforcement of the CrPC, on the basis of the reports of the Law Commission, an amendment was made to Section 372 CrPC by insertion of the proviso thereto with effect from 31.12.2009. Consequently, the definition of ‘victim’ was also inserted to Section 2(wa) of CrPC which reads as under:

“2(wa)-“victim” means a person who has suffered any loss or injury caused by reason of the act or omission for which the accused person has been charged and the expression “victim” includes his or her guardian or legal heir;”

5.1 Simultaneously, proviso to Section 372 CrPC was inserted which reads as under:

“372. No appeal to lie unless otherwise provided.- No appeal shall lie from any judgment or order of a Criminal Court except as provided for by this Code or by any other law for the time being in force.

Provided that the victim shall have a right to prefer an appeal against any order passed by the Court acquitting the accused or convicting for a lesser offence or imposing inadequate compensation, and such appeal shall lie to the Court to which an appeal ordinarily lies against the order of conviction of such Court.”

5.2 A conjoint reading of the proviso to Section 372 CrPC in light of the definition in Section 2(wa) of CrPC, would lead to the conclusion that the expression ‘victim’ is not restricted to any person who has suffered any loss or injury caused by reason of the act or omission for which the accused person has been charged. It also includes a person who is a guardian or legal heir of a victim as defined above.

5.3 In the instant cases, the legal heir of the injured victim and himself being an injured victim had preferred these appeals as he had every right to do so particularly having regard to amendment made to the CrPC with effect from 31.12.2009 by insertion of the proviso to Section 372 CrPC. However, the contentious issue in these cases is, whether a legal heir of a legal heir, who had preferred these appeals, could also continue to prosecute these appeals as during the pendency of these appeals the original appellant has died. We are considering this issue irrespective of the fact that the applicant who seeks substitution as an appellant in these appeals is himself an injured victim in the incident and in his own right could have filed appeals against the acquittal of the accused. However, he has filed the applications for substitution in place of his father as a legal heir of an injured victim, the original appellant in these appeals.

5.4 We have considered the arguments advanced at the bar in light of the amendment made to Section 372 CrPC and also the insertion of the expression ‘Victim’ by way of a definition clause to Section 2 of the Act extracted above and generally in light of Article 14 of the Constitution including the right to equal opportunity before law and right to access to justice.

6. In Mallikarjun Kodagali (dead) represented through Legal representatives State of Karnataka, (2019) 2 SCC 752 (“Mallikarjun Kodagali”), there is a reference to four reports that have dealt with the rights of victims of crime and the remedies available to them. The same may be briefly discussed as under:

- The first report is the 154th Report of the Law Commission of India of August, 1996. The said Report touched upon, inter alia, compensation to be paid to the victim of crime, their rehabilitation, etc.

- In March 2003, Justice Malimath Committee submitted its report on ‘Reforms of Criminal Justice System’. Paragraph 21 in the Chapter on Adversarial Rights under the sub-heading of ‘Victims Right to Appeal’, states as under:

“2.21. The victim or his representative who is a party to the trial should have a right to prefer an appeal against any adverse order passed by the trial court. In such an appeal he could challenge the acquittal, or conviction for a lesser offence or inadequacy of sentence, or in regard to compensation payable to the victim. The appellate court should have the same powers as the trial court in regard to assessment of evidence and awarding of sentence.”

There is also discussion on other rights of victims under the Chapter titled, ‘Justice to Victims’. In paragraph 6.(14)(v), Justice Malimath Committee made the following recommendations:

“6. (14)(v) The victim shall have a right to prefer an appeal against any adverse order passed by the court acquitting the accused, convicting for a lesser offence, imposing inadequate sentence, or granting inadequate compensation. Such appeal shall lie to the court to which an appeal ordinarily lies against the order of conviction of such court.”

- In July 2007, a Report of the Committee on the Draft National Policy on Criminal Justice was submitted which is also known as ‘Professor Madhava Menon Committee Report’. Observations with regard to providing victim-oriented criminal justice and a balance between the constitutional rights of an accused and victim of crime have been discussed. One of the suggestions made is that the victim must be impleaded in the trial proceedings so that such a party would have a right to file an appeal against an adverse order, particularly an order of aquittal.

- In the 221st Report of the Law Commission of India submitted in April, 2009, it has been noted that as the law then stood, an aggrieved person could not file an appeal against an order of acquittal. However, a revision petition could be filed. Noting that the powers of a revisional court are limited and the process involved is cumbersome, a recommendation was made by the Law Commission that as against an order of acquittal passed by a Magistrate, a victim should be entitled to file an appeal before the revisional court. Similarly, in complaint cases, the appeal should be provided to the Sessions Court instead of the High Court. However, it was suggested that the aggrieved person or complainant should have the right to prefer an appeal with the leave of the appellate court.

- It was further recommended that Section 378 CrPC requires an amendment with a view to enable filing of appeals in complaint cases also in the Sessions Court, of course, subject to the grant of special leave by it. Limited scope of powers of a revisional court under Section 401 CrPC was taken note of and it was suggested that there is a need to amend the CrPC.

6.1 Taking note of the aforesaid reports, an amendment was brought to Section 372 CrPC with effect from 12.2009 by adding a proviso thereto.

6.2 The decisions of the Full Benches of the High Courts in the matter of interpretation of the proviso to Section 372 CrPC are highlighted by this Court in the case of Mallikarjun Kodagali. There are also Division Bench decisions of the High Courts taking different views.

Mallikarjun Kodagali:

6.3 This Court in Mallikarjun Kodagali, speaking through Lokur, for himself and Nazeer, J. referred to the Declaration of the Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in the 96th Plenary Session on 29.11.1985. It was observed in paragraphs 74, 75 & 76 as under:

“74. Putting the Declaration to practice, it is quite obvious that the victim of an offence is entitled to a variety of rights. Access to mechanisms of justice and redress through formal procedures as provided for in national legislation, must include the right to file an appeal against an order of acquittal in a case such as the one that we are presently concerned with. Considered in this light, there is no doubt that the proviso to Section 372 CrPC must be given life, to benefit the victim of an offence.

75. Under the circumstances, on the basis of the plain language of the law and also as interpreted by several High Courts and in addition the resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations, it is quite clear to us that a victim as defined in Section 2(wa) CrPC would be entitled to file an appeal before the Court to which an appeal ordinarily lies against the order of conviction. …

76. … The language of the proviso to Section 372 CrPC is quite clear, particularly when it is contrasted with the language of Section 378(4) The text of this provision is quite clear and it is confined to an order of acquittal passed in a case instituted upon a complaint. The word “complaint” has been defined in Section 2(d) CrPC and refers to any allegation made orally or in writing to a Magistrate. This has nothing to do with the lodging or the registration of an FIR, and therefore it is not at all necessary to consider the effect of a victim being the complainant as far as the proviso to Section 372 CrPC is concerned.”

6.4 Consequently, the appeals in the said case were allowed and the judgment and order of the High Court was set aside and the matter was remanded to the High Court to hear and decide the appeal against the judgment and order of acquittal once again.

Analysis of the Relevant Provisions of CrPC:

7. Section 2 CrPC is the definition clause under which relevant definitions are extracted as under:

“2. Definitions.—In this Code, unless the context otherwise requires,—

xxx

(d) “complaint” means any allegation made orally or in writing to a Magistrate, with a view to his taking action under this Code, that some person, whether known or unknown, has committed an offence, but does not include a police report.

Explanation.—A report made by a police officer in a case which discloses, after investigation, the commission of a non-cognizable offence shall be deemed to be a complaint; and the police officer by whom such report is made shall be deemed to be the complainant;

xxx

(n) “offence” means any act or omission made punishable by any law for the time being in force and includes any act in respect of which a complaint may be made under section 20 of the Cattle Trespass Act, 1871 (1 of 1871);

xxx

24. Public Prosecutors.-

xxx

(8) The Central Government or the State Government may appoint, for the purposes of any case or class of cases, a person who has been in practice as an advocate for not less than ten years as a Special Public Prosecutor:

Provided that the Court may permit the victim to engage an advocate of his choice to assist the prosecution under this sub-section.

CHAPTER XXIX

APPEALS

372. No appeal to lie unless otherwise provided.—No appeal shall lie from any judgment or order of a Criminal Court except as provided for by this Code by any other law for the time being in force:

Provided that the victim shall have a right to prefer an appeal against any order passed by the Court acquitting the accused or convicting for a lesser offence or imposing inadequate compensation, and such appeal shall lie to the Court to which an appeal ordinarily lies against the order of conviction of such Court.

xxx

377. Appeal by the State Government against sentence.—(1) Save as otherwise provided in sub-section (2), the State Government may, in any case of conviction on a trial held by any Court other than a High Court, direct the Public Prosecutor to present an appeal against the sentence on the ground of its inadequacy—

(a) to the Court of Session, if the sentence is passed by the Magistrate; and

(b) to the High Court, if the sentence is passed by any other Court.

(2) If such conviction is in a case in which the offence has been investigated by the Delhi Special Police Establishment, constituted under the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, 1946 (25 of 1946), or by any other agency empowered to make investigation into an offence under any Central Act other than this Code, the Central Government may also direct the Public Prosecutor to present an appeal against the sentence on the ground of its inadequacy—

(a) to the Court of Session, if the sentence is passed by the Magistrate; and

(b) to the High Court, if the sentence is passed by any other Court.

(3) When an appeal has been filed against the sentence on the ground of its inadequacy, the Court of Session or, as the case may be, the High Court shall not enhance the sentence except after giving to the accused a reasonable opportunity of showing cause against such enhancement and while showing cause, the accused may plead for his acquittal or for the reduction of the sentence.

(4) When an appeal has been filed against a sentence passed under section 376, section 376A, section 376AB, section 376B, section 376C, section 376D, section 376DA, section 376DB or section 376E of the Indian Penal Code (45 of 1860), the appeal shall be disposed of within a period of six months from the date of filing of such appeal.

378. Appeal in case of acquittal.—(1) Save as otherwise provided in sub-section (2), and subject to the provisions of sub-sections (3) and (5),—

(a) the District Magistrate may, in any case, direct the Public Prosecutor to present an appeal to the Court of Session from an order of acquittal passed by a Magistrate in respect of a cognizable and non-bailable offence;

(b) the State Government may, in any case, direct the Public Prosecutor to present an appeal to the High Court from an original or appellate order of acquittal passed by any Court other than a High Court not being an order under clause (a) or an order of acquittal passed by the Court of Session in revision.

(2) If such an order of acquittal is passed in any case in which the offence has been investigated by the Delhi Special Police Establishment constituted under the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, 1946 (25 of 1946), or by any other agency empowered to make investigation into an offence under any Central Act other than this Code, the Central Government may, subject to the provisions of sub- section (3), also direct the Public Prosecutor to present an appeal—

(a) to the Court of Session, from an order of acquittal passed by a Magistrate in respect of a cognizable and non-bailable offence;

(b) to the High Court from an original or appellate order of an acquittal passed by any Court other than a High Court not being an order under clause (a) or an order of acquittal passed by the Court of Session in

(3) No appeal to the High Court under sub-section (1) or sub-section (2) shall be entertained except with the leave of the High Court.

(4) If such an order of acquittal is passed in any case instituted upon complaint and the High Court, on an application made to it by the complainant in this behalf, grants special leave to appeal from the order of acquittal, the complainant may present such an appeal to the High

(5) No application under sub-section (4) for the grant of special leave to appeal from an order of acquittal shall be entertained by the High Court after the expiry of six months, where the complainant is a public servant, and sixty days in every other case, computed from the date of that order of acquittal.

(6) If, in any case, the application under sub-section (4) for the grant of special leave to appeal from an order of acquittal is refused, no appeal from that order of acquittal shall lie under sub-section (1) or under sub-section (2).

xxx

386. Powers of the Appellate Court.—After perusing such record and hearing the appellant or his pleader, if he appears, and the Public Prosecutor if he appears, and in case of an appeal under section 377 or section 378, the accused, if he appears, the Appellate Court may, if it considers that there is no sufficient ground for interfering, dismiss the appeal, or may—

(a) in an appeal from an order or acquittal, reverse such order and direct that further inquiry be made, or that the accused be re-tried or committed for trial, as the case may be, or find him guilty and pass sentence on him according to law;

(b) in an appeal from a conviction—

(i) reverse the finding and sentence and acquit or discharge the accused, or order him to be re- tried by a Court of competent jurisdiction subordinate to such Appellate Court or committed for trial, or

(ii) alter the finding, maintaining the sentence, or

(iii) with or without altering the finding, alter the nature or the extent, or the nature and extent, of the sentence, but not so as to enhance the same—

(c) in an appeal for enhancement of sentence—

(i) reverse the finding and sentence and acquit or discharge the accused or order him to be re- tried by a Court competent to try the offence, or

(ii) alter the finding maintaining the sentence, or

(iii) with or without altering the finding, alter the nature or the extent, or, the nature and extent, of ) the sentence, so as to enhance or reduce the same;

(d) in an appeal from any other order, alter or reverse such order;

(e) make any amendment or any consequential or incidental order that may be just or proper:

Provided that the sentence shall not be enhanced unless the accused has had an opportunity of showing cause against such enhancement:

Provided further that the Appellate Court shall not inflict greater punishment for the offence which in its opinion the accused has committed, than might have been inflicted for that offence by the Court passing the order or sentence under appeal.

394. Abatement of appeals. Every appeal under Section 377 or Section 378 shall finally abate on the death of the accused.

(2) Every other appeal under this Chapter (except an appeal from a sentence of fine) shall finally abate on the death of the appellant:

Provided that where the appeal is against a conviction and sentence of death or of imprisonment, and the appellant dies during the pendency of the appeal, any of his near relatives may, within thirty days of the death of the appellant, apply to the Appellate Court for leave to continue the appeal; and if leave is granted, the appeal shall not abate.

Explanation.- In this section, “near relative” means a parent, spouse, lineal descendant, brother or sister.”

7.1 Chapter XXIX of the CrPC deals with The said Chapter delineates the statutory framework governing appeals. Section 372 CrPC unequivocally declares that no appeal shall lie from any judgment or order of a criminal court except as provided for by the CrPC itself or by any other law for the time being in force. In fact, Section 372 CrPC speaks of an embargo on the filing of an appeal from any judgment or order of a criminal court except as provided for by the CrPC or by any other law for the time being in force. Section 372 CrPC is couched in a negative language and it states that no appeal shall lie from any judgment or order of a criminal court except as provided for by the CrPC or by any other law for the time being in force. Section 372 CrPC is a preface to the chapter on appeals which in substance states that an appeal can be filed only in accordance with what has been stated in the provisions to follow Section 372 CrPC. The proviso to Section 372 was introduced by the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 2008 (Act 5 of 2009), which came into effect from 31.12.2009. By virtue of this amendment, a limited right of appeal has been conferred upon the victim of an offence. On a reading of the proviso to Section 372 CrPC, it is apparent that a victim shall have a right to prefer an appeal against: (i) any order passed by the court acquitting the accused; or (ii) convicting for a lesser offence; or (iii) imposing inadequate compensation. Such appeal shall lie to the court to which an appeal ordinarily lies against the order of conviction of such court. In fact, with effect from 31.12.2009 when clause (wa) to Section 2 CrPC was inserted to the definition of victim, proviso to Section 24 was also added which provides that the Court may permit the victim to engage an advocate of his choice to assist the prosecution under the said sub-section.

7.1.1 Further, with effect from 31.12.2009, Section 357A and Section 357B were inserted to the CrPC in the form of victim compensation scheme for providing compensation to the victim or his dependants who have suffered loss or injury as a result of the crime and who require rehabilitation. The compensation payable by the State Government under Section 357A is in addition to the payment of fine to the victim of offences under Section 326A, Section 376AB, Section 376D, Section 376DA and Section 376DB of the Indian Penal Code. Also, Section 357C states that all hospitals, public or private, whether run by the Central Government, the State Government, local bodies or any other person, shall immediately provide first-aid or medical treatment, free of cost, to the victims of any offence covered under the aforesaid Sections.

7.2 While Section 374 CrPC deals with appeals from convictions with which we are not concerned in this case, what is of relevance is Section 378 CrPC which, inter alia, deals with an appeal in case of The remedy of an appeal against an acquittal is couched in certain conditions which are evident on a reading of sub-sections (4) and (5) of Section 378 CrPC vis-à-vis an appeal that could be filed by a complainant. However, the Parliament in its wisdom amended Section 372 CrPC by adding a proviso thereto by virtue of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act 2008 (5 of 2009), (with effect from 31.12.2009). It is hence necessary to unravel the definition of victim in clause (wa) of Section 2 of the CrPC which was also introduced along with proviso to Section 372 CrPC. A victim is defined to mean a person who has suffered any loss or injury caused by reason of the act or omission for which the accused person has been charged and the expression ‘victim’ includes his or her guardian or legal heir.

7.3 The expression ‘injury’, as defined in Section 44 of the IPC includes:

“Any harm whatever illegally caused to any person, in body, mind, reputation or property.”

7.3.1 Similarly, Black’s Law Dictionary defines injury to include property damage, bodily harm, or violation of a legal right.

7.3.2 Additionally, the United Nations General Assembly’s Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power (1985) provides a broad and inclusive definition of victim. According to Article 1 of the Declaration:

“Victim means persons who, individually or collectively, have suffered harm through acts or omissions which involve physical or mental injury, emotional distress, economic loss or substantial impairment of their fundamental rights.”

7.3.3 Further, Article 2 extends the definition of victim to include immediate family members, dependents, or those who have intervened to assist a victim in crisis.

7.4 On a reading of the definition of ‘victim’, it is clear that the said expression is initially exhaustive and thereafter inclusive. The expression ‘victim’ means a person who has suffered any loss or injury. The loss or injury could be either physical, mental, a financial loss or injury. The expression ‘injury’ could also be construed as a legal injury in a wider sense and not just a physical or a mental injury. The loss or injury must be caused by reason of an act or omission for which the accused person has been charged. Thus, it can be both by a positive act or negatively by an omission which is at the instance of the accused and for which such accused has been charged. Further, the expression ‘victim’ also includes his/her guardian or legal heir in the case of demise of the victim.

7.5 Thus, the expression ‘victim’ has been couched in a broad manner so as to include a person who has suffered any loss or injury. The expressions ‘loss’ or ‘injury’ themselves are of a very broad import which expressions also enlarge the scope of the expression ‘victim’. Further, the expression ‘victim’ includes not only the person who has suffered any loss or injury caused by reason of any act or omission for which the accused person has been charged but also includes his or her guardian or legal heir which means that the definition of victim is inclusive in nature.

7.6 Having regard to the insertion of the proviso to Section 372 CrPC, we find that in the case of a victim who seeks to file an appeal, he or she could proceed under the proviso to Section 372 CrPC in the circumstances mentioned therein and need not prefer an appeal by invoking Section 378(4) CrPC which is in respect of appeals to be filed by a complainant. It may be that the complainant is a victim in certain cases and therefore, the victim has the right to file an appeal under the proviso to Section 372 CrPC and need not proceed under Section 378(4) CrPC. However, if the complainant is not a victim and intends to file an appeal, in such a case a complainant would have to proceed under Section 378 CrPC which circumscribes the right to file an appeal by virtue of the conditions which are stipulated under the said Section.

7.6.1 The word ‘victim’ is derived from the latin word “victima” and originally contained the concept of sacrifice. In more contemporary times, the term ‘victim’ has been expanded to imply a victim of war, an accident, a scam, etc. As a scientific concept, according to Criminologist Mendelsohn (1976), a victim may be viewed as containing four fundamental criteria which are as follows:

- The nature of the determinant that causes the suffering. The suffering may be physical, psychological, or both, depending on the type of injurious act.

- The social character of the suffering. This suffering originates in the victim’s and others’ reaction to the event.

- The nature of the social factor. The social implications of the injurious act can have a greater impact, sometimes, than the physical or psychological impact.

- The origin of the inferiority complex. This term, suggested by Mendelsohn, manifests itself as a feeling of submission that may be followed by a feeling of revolt. The victim generally attributes his injury to the culpability of another person.

Victimology thus is a social-structural way of viewing crime, the law, the criminal and the victim. Insofar as the injury is concerned, apart from there being short time and long time physical injuries, there could also be economic or financial loss which are also injuries within the meaning and definition of victim under clause (wa) of Section 2 CrPC. We could also place reliance on Dr. Vimla vs. State (NCT of Delhi), AIR 1963 SC 1572, wherein the expression “injury” has been explained to mean something other than economic loss i.e., deprivation of property, whether movable or immovable, or of money, and to include any harm whatever caused to any person in body, mind, reputation or such others. In short, it is a non-economic or non-pecuniary loss.

7.7 Further, while analysing the expression ‘victim’, it is noted that it is with reference to an accused person who has been charged. Under the CrPC, the expression ‘charge’ is defined under clause (b) of Section 2 which reads as under:

“2. Definitions.—In this Code, unless the context otherwise requires,—

xxx

(b) “charge” includes any head of charge when the charge

contains more heads than one;

7.7.1 Besides the omnibus meaning, the CrPC does not define what a charge is. However, judicial pronouncements tell us that a charge is actually a precise formulation of the specific accusation made against a person who is entitled to know its nature at the earliest stage. The charge is against a person in respect of an act committed or omitted in violation of penal law forbidding or commanding it. In other words, a charge is an accusation made against a person in respect of offence alleged to have been committed by him, vide Esher Singh vs. State A.P., (2004) 11 SCC 585. In Birichh Bhuian vs. State of Bihar, AIR 1963 SC 1120, this Court observed that a charge is not a mere abstraction but a concrete accusation against a person in respect of an offence and that joinder of charges is permitted under certain circumstances, whether joinder is against one person or different persons.

7.7.2 In Advanced Law Lexicon by P Ramanatha Aiyar, 6th Edition, Volume I, a charge is defined to mean an expression as applied to a crime, sometimes used in a limited sense, intending the accusation of a crime which precedes a formal trial; to mean a person charged with an accusation of a crime. In a fuller and more accurate sense, the expression charge includes the responsibility for the crime. As a formal complaint, a charge signifies an accusation, made in a legal manner of legal conduct, either of omission or commission by the person charged. A person charged with a crime means something more than being suspected or accused of a crime by popular opinion or rumour and implies that the offence has been alleged against the accused parties according to the forms of The purpose of a charge is to tell an accused person as precisely and consciously as possible of the matter with which he is charged with. Thus, the expression charge includes the element of offence and also reference to the person who is alleged to have committed the offence.

8. Section 378 CrPC is a specific provision dealing with appeals. Sub-section (4) of Section 378 CrPC is pertinent. It states that if an order of acquittal is passed in any case instituted upon a complaint and the High Court, on an application made to it by the complainant in that behalf, grants special leave to appeal from the order of acquittal, the complainant may present such an appeal to the High Court. The limitation period for seeking special leave to appeal is six months where the complainant is a public servant and sixty days in every other case, computed from the date of the order of acquittal. Sub-Section (6) states that if, in any case, the application under sub-section (4) for grant of special leave to appeal from an order of acquittal is refused, no appeal from that order of acquittal shall lie under sub-section (1) or under sub-section (2) of Section 378 CrPC.

8.1 A reading of section 378 CrPC would clearly indicate that in case the complainant intends to file an appeal against the order of acquittal, his right is circumscribed by certain conditions precedent. When an appeal is to be preferred by a complainant, the first question is, whether the complainant is also the victim or only an informant. If the complainant is not a victim and the case is instituted upon a complaint, then sub-section (4) requires that the complainant must seek special leave to appeal from an order of acquittal from the High Court. As noted under sub-section (6), if the application under sub-section (4) for grant of special leave to appeal from the order of acquittal is refused, no appeal from that order of acquittal would lie, inter alia, under sub-section (1) of Section 378 CrPC. However, if the complainant is also a victim, he could proceed under the proviso to Section 372 CrPC, in which case the rigour of sub-section (4) of Section 378 CrPC, which mandates obtaining special leave to appeal, would not arise at all, as he can prefer an appeal as a victim as a matter of right. Thus, if a victim who is a complainant proceeds under Section 378 CrPC, the necessity of seeking special leave to appeal would arise but if a victim, whether he is a complainant or not, files an appeal in terms of proviso to Section 372 CrPC, then the mandate of seeking special leave to appeal would not arise.

8.2 The reasons for the above distinction are not far to see and can be elaborated as follows:

Firstly, the victim of a crime must have a right to prefer an appeal which cannot be circumscribed by any condition precedent except as provided under the provision of the CrPC.

Secondly, the right of a victim of a crime must be placed on par with the right of an accused who has suffered a conviction, who, as a matter of right can prefer an appeal under Section 374 CrPC. A person convicted of a crime has the right to prefer an appeal under Section 374 CrPC as a matter of right and not being subjected to any conditions. Similarly, a victim of a crime, whatever be the nature of the crime, must have a right to prefer an appeal as per the CrPC.

Thirdly, it is for this reason that the Parliament thought it fit to insert the proviso to Section 372 CrPC without mandating any condition precedent to be fulfilled by the victim of an offence, which expression also includes the legal representatives of a deceased victim who can prefer an appeal.

On the contrary, as against an order of acquittal, the State, through the Public Prosecutor, can prefer an appeal even if the complainant does not prefer such an appeal, though of course such an appeal is with the leave of the court. However, it is not always that the State or a complainant would prefer an appeal. But when it comes to a victim’s right to prefer an appeal, the insistence on seeking special leave to appeal from the High Court under Section 378(4) CrPC would be contrary to what has been intended by the Parliament by insertion of the proviso to Section 372 CrPC.

Fourthly, the Parliament has not amended Section 378 CrPC which deals with appeals against acquittal to circumscribe the victim’s right to prefer an appeal just as it has with regard to a complainant or the State filing an appeal. On the other hand, the Parliament has inserted the proviso to Section 372 CrPC so as to envisage a superior right for the victim of an offence to prefer an appeal on the grounds mentioned therein as compared to a complainant.

9. The right to prefer an appeal is no doubt a statutory right and such a right in an accused against a conviction is not merely a statutory right but can also be construed to be a fundamental right under Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. If that is so, then the right of a victim of an offence to prefer an appeal cannot be equated with the right of the State or the complainant to prefer an appeal unless the victim is also the complainant. Hence, the statutory rigours for filing of an appeal by the State or by a complainant against an order of acquittal cannot be read into the proviso to Section 372 CrPC so as to restrict the right of a victim to file an appeal on the grounds mentioned therein, when none exists.

9.1 As already noted, the proviso to Section 372 CrPC was inserted in the statute book only with effect from 31.12.2009. The object and reason for such insertion must be realised and must be given its full effect to by a In view of the aforesaid discussion, we hold that the victim of an offence has the right to prefer an appeal under the proviso to Section 372 CrPC, irrespective of whether he is a complainant or not. Even if the victim of an offence is a complainant, he can still proceed under the proviso to Section 372 CrPC and need not advert to sub-section (4) of Section 378 CrPC.

9.2 We find that on the recommendation made by the Law Commission, the Parliament inserted the proviso in order to give an independent right to a victim to prefer an appeal under the circumstances mentioned under the proviso. This is de hors an appeal that could be filed by the complainant under Section 378(4) CrPC. The object and purpose of giving an independent right to a victim to prefer an appeal is particularly in a case where a complainant may not file an appeal and the State also would decide not to prefer an appeal as against the acquittal or award of a lesser sentence to an accused. If we bear in mind the object with which the amendment has been made by the Parliament, we find that the victim has every right to prefer an appeal as against a conviction for a lesser offence or for imposing inadequate compensation or even in the case of an acquittal of an accused as stated in the proviso to Section 372 CrPC. There is no doubt that in the instant cases they are cases of acquittal of the accused by the High Court.

9.3 The expression ‘right to prefer an appeal’ in the proviso to Section 372 CrPC cannot be limited to mean ‘only the filing of an appeal’. Mere filing of an appeal in the absence of prosecution of an appeal is of no avail. It does not fulfill the object with which the proviso has been added to Section 372 Therefore, we interpret the expression ‘the right to prefer an appeal’ to also include the ‘right to prosecute an appeal’. Then, if during the pendency of an appeal, the original appellant dies, can it be said that his legal heir cannot be substituted so as to prosecute the appeal further? Any curtailing of the legal right to prosecute an appeal on the death of an original appellant by his legal heir would make the proviso to Section 372 CrPC wholly redundant and in fact may result in a situation which is contrary to the entire object with which the Parliament had inserted the proviso to Section 372 CrPC. In this context, it is also relevant to note that the Parliament has been conscious to expand the definition of the word ‘victim’ to not only include the victim himself who had suffered the loss or injury but also to include his legal heir. When a legal heir, who is not a complainant or an injured victim, can prefer an appeal then why not his legal heir on the death of the legal heir who had preferred the appeal be permitted to prosecute the appeal? We see no reason to curtail the right of a legal heir, who had preferred the original appeal, to be denied the right to prosecute the appeal. In the instant cases, the applicant, who is seeking substitution, is the legal heir of the victim who had preferred the appeal before this Court and is also an injured victim.

Relevant Judicial Dicta:

10. A Constitution Bench of this Court in PSR Sadhanantham, speaking through Krishna Iyer, J., observed that in a murder case, when an appeal against acquittal was not filed by the State but by a brother of the deceased, a private citizen, who is neither a complainant nor the first informant, could invoke the special power under Article 136 of the Constitution for leave to appeal against an acquittal, the same would not violate Article 21 of the Constitution. The facts of the said case were that the petitioner therein was acquitted of a murder charge by the High Court but the brother of the deceased — not the State nor even the first informant — moved this Court under Article 136, got leave and had his appeal heard which resulted in the petitioner (accused) being convicted and sentenced to life term under Section 302 IPC. A writ petition was filed by the accused challenging the locus standi of the brother of the deceased in moving this Court under Article 136 of the Constitution.

10.1 It was observed that Article 136 of the Constitution is of composite structure wherein power-cum-procedure is in-built which vests power in this Court to entertain a petition and prescribes a mode of hearing so characteristic of the Court process. When a motion is made for leave to appeal against an acquittal, this Court has to appreciate the gravity of the peril to personal liberty involved in that proceeding. The Court will also pay attention to the person who seeks such leave from the Court, his motive and his locus standi and the weighty factors which persuade the Court to grant special leave. The Court may not, save in special situations, grant leave to one who is not eo nomine a party on the record.

10.1.1 This Court observed that the strictest vigilance over abuse of the process of the Court is necessary, as ordinarily meddlesome bystanders should not be granted a “visa”, but access to justice to every bona fide seeker is a democratic dimension of remedial jurisprudence. It was further observed that while the criminal law should not be used as a weapon in personal vendettas between private individuals, in the absence of an independent prosecution authority easily accessible to every citizen, a wider connotation of the expression “standing” is necessary for Article 136 to further its mission.

10.1.2 Pathak, J. (as he then was) writing a separate judgment for himself and Koshal, J. considered the question whether a brother of a deceased person, who had been murdered, possessed the right to petition under Article 136 of the Constitution for special leave to appeal against an acquittal of the accused. It was observed that this question touched directly on the nature of the crime and of a criminal proceeding. When entertaining a petition for special leave to appeal by a private party against an order of acquittal, certain factors to be borne in mind were also enumerated. It was opined that the judicial process under Article 136 ought not to be invoked for the satisfaction of private revenge or persona vendetta. Nor can it be permitted as an instrument of coercion where a civil action would lie. In every case, this Court is bound to consider what is the interest which brings the petitioner to this Court and whether the interest of the public community will benefit by the grant of special leave. This Court should closely scrutinise the motives and urges of those who seek to employ its process against the life or liberty of another. The Court should entertain a special leave petition filed by a private party, other than the complainant, in those cases only where it is convinced that the public interest justifies an appeal against the acquittal and that the State has refrained from petition for special leave for reasons which do not bear on the public interest but are prompted by private influence, want of bona fide and other extraneous considerations. Therefore, locus standi of the petitioner must be recognised in law. It was observed that the petitioner therein had failed to establish that there was a case for interfering with the judgment of this Court allowing the appeal and hence, the writ petition was dismissed.

10.2 In Chand Devi Daga vs. Manju K. Humatani, (2018) 1 SCC 71, the original complainant had died during the pendency of the criminal miscellaneous petition before the High Court which was filed against the order of the Sessions Court rejecting the criminal revision against the order of the Magistrate dismissing the complaint. The High Court allowed the interlocutory application filed by the legal representatives of the petitioner in the criminal miscellaneous petition. The respondent before the High Court, being aggrieved by the said order, had filed an appeal before this Court. Referring to Section 256 CrPC, this Court observed that even in case of trial of summons case, it is not necessary or mandatory that after the death of the complainant, the complaint has to be rejected. Under the proviso to the said Section, the Magistrate can proceed with the complaint. That a similar provision with regard to trial of warrant cases by the Magistrate is not provided for under the CrPC but the Magistrate has the power to discharge a case where the complainant is absent under Section 249 which is, however, hedged with a condition that “the offence may be lawfully compounded or is not a cognizable offence”. Therefore, there is no indication that on the death of the complainant, the complaint has to be rejected in a warrant case. Referring to certain other judicial dicta, this Court observed that the High Court did not commit any error in allowing the legal heirs of the complainant to prosecute the criminal miscellaneous petition before the High Court and consequently, dismissed the appeal.

10.3 In M.R. Ajayan vs. State of Kerala, 2024 SCC OnLine SC 3373, this Court considered the locus of a private individual seeking exercise of jurisdiction of this Court under Article 136 of the Constitution. Placing reliance on National Commission for Women vs. State of Delhi, (2010) 12 SCC 599; Amanullah vs. State of Bihar, (2016) 6 SCC 699 (“Amanullah”) and PSR Sadhanantham, it was observed that the appellant therein had locus standi to prosecute the special leave petition before this Court. Referring to the observations of this Court in Amanullah, it was stated that it may not be possible to strictly enumerate as to who all will have locus to maintain an appeal before this Court invoking Article 136 of the Constitution of India as that would depend upon the factual matrix of each case, as each case has its unique set of facts. In other words, any person having a bona fide connection with the matter, to maintain the appeal with a view to advance substantial justice, must be permitted to do so.

10.4 We take note of the aforesaid judgments of this Court which are judgments rendered in the context of Article 136 of the Constitution of India as they would squarely apply to the present case as apart from the original appellant herein the applicant (injured victim) could have also preferred a Special Leave Petition under Article 136 of the Constitution of India in his own right but instead he is now seeking to prosecute these Criminal Appeals as an heir of the original appellant who was a victim. Although PSR Sadhanantham is a case which arose in a petition filed under Article 32 of the Constitution of India, nevertheless the question which arose therein is similar to the question in the present case and therefore, the observations therein squarely apply.

11. We are conscious of the fact that the applicant who is seeking substitution in the instant case is not only the son and heir of the original appellant who preferred these appeals but is also an injured victim in the incident which occurred on 09.12.1992 in respect of which these appeals have been filed. Therefore, the applicant could have filed these appeals assailing the judgment of acquittal passed by the High Court in his individual capacity as an injured victim. However, the applications for substitution have been filled in order to continue the prosecution of these appeals as the heir of the original appellant who was also an injured victim. Hence, the detailed discussion that we have made is in acceptance of the argument of learned counsel for the applicant that as heir of the original appellant, who was an injured victim, he can prosecute these appeals. Therefore, the applicant is being permitted to be substituted in place of the original appellant as heir of the original appellant (who was a victim in the incident). In other words, we observe that even if the applicant was not an injured victim in the said incident but has sought to prosecute these appeals as heir of

the injured victim (original appellant), he is permitted to do so. We therefore say, coincidentally, the applicant is also an injured victim in the incident. In view of the above discussion, we do not accept the contention of learned senior counsel for the respondent- accused that the applicant herein would have to separately file appeals before this Court as an injured victim and in that capacity only and not as heir of the original appellant.

11.1 Secondly, another contention of learned senior counsel for the respondent-accused is that under Section 394(2) CrPC, the expression “every other appeal” other than an appeal filed under Section 377 CrPC or Section 378 CrPC shall finally abate applies to an appeal filed by a victim. We do not think the same can be simply applied to an appeal filed by a victim or an heir of the victim. Although, sub-section (2) of Section 394 CrPC states that “every other appeal under this Chapter shall finally abate on the death of the appellant”, it cannot be related to an appeal filed by a victim or on the death of the victim/appellant. This is because Sections 377 and 378 CrPC respectively deal with an appeal filed by the State Government against sentence and an appeal in case of acquittal. Such appeals are filed against the accused and therefore, when the accused dies, such appeals would abate. The expression “every other appeal” must therefore, relate to an appeal which is not filed under Section 377 or Section 378 CrPC. Such an appeal is an appeal against a conviction such as under Section 374 CrPC and on the death of the appellant who is the accused, such appeal would abate. The proviso to sub-section (2) of Section 394 CrPC however, states, that even if the accused-appellant dies during the pendency of the appeal, any of his near relatives may continue the appeal and the appeal may not abate. In other words, the heirs of the deceased accused-appellant have been permitted to continue the appeals so as to seek an acquittal and realise the fruits of such an acquittal which could be even in monetary terms despite the death of the accused-appellant.

11.2 If the same logic is to apply to the proviso to Section 372 CrPC, it would imply that the heirs of a victim can also pursue an appeal filed under that provision as the definition of victim under Section 2(wa) includes the heir of a victim.

11.3 The expression “prefer an appeal” in proviso to Section 372 CrPC has to be given an expanded meaning to include prosecution of an appeal or effectively pursue an appeal. According to Black’s Law Dictionary, the word “prefer” means “to bring before; to prosecute; to try; to proceed with. Thus, preferring an indictment signifies prosecuting or trying an indictment; – Manik Lal Majumdar vs. Gouranga Chandra Dey, (2004) 12 SCC 448.

11.4 We may usefully refer to Constitution Bench Judgment of this Court in Garikapati Veeraya vs. N. Subbiah Choudhry, AIR 1957 SC 540, wherein it was observed thus:

“23. From the decisions cited above the following principles clearly emerge:

(i) That the legal pursuit of a remedy, suit, appeal and second appeal are really but steps in a series of proceedings all connected by an intrinsic unity and are to be regarded as one legal proceeding.

(ii) The right of appeal is not a mere matter of procedure but is a substantive right.

(iii) The institution of the suit carries with it the implication that all rights of appeal then in force are preserved to the parties thereto till the rest of the career of the suit.

(iv) The right of appeal is a vested right and such a right to enter the superior court accrues to the litigant and exists as on and from the date the lis commences and although it may be actually exercised when the adverse judgment is pronounced such right is to be governed by the law prevailing at the date of the institution of the suit or proceeding and not by the law that prevails at the date of its decision or at the date of the filing of the appeal.

(v) This vested right of appeal can be taken away only by a subsequent enactment, if it so provides expressly or by necessary intendment and not otherwise.”

11.5 More importantly, Article 136 of the Constitution deals with Special leave to appeal by the Supreme Court. Sub-clause (1) of Article 136 begins with a non-obstante clause and confers discretion on the Supreme Court to grant special leave to appeal from any judgment, decree, determination, sentence or order in any cause or matter passed or made by any court or tribunal in the territory of India. When this power under Article 136 is exercised by the Supreme Court by granting leave, the special leave petition would get converted into a criminal appeal. If during the pendency of the special leave petition or the criminal appeal, the appellant dies, the heir of the appellant must be given an opportunity to prosecute the appeal irrespective of whether the heir is a victim of the criminal offence. More significantly, the appeal heard pursuant to Article 136 of the Constitution is not an appeal under Chapter XXIX CrPC.

11.6 In the circumstances, we find that in the instant case, the applicant, being heir of the victim, has the right to continue these appeals irrespective of the fact that he is an injured victim. In that view of the matter also, we find that the application for substitution has to be allowed.

11.7 However, if in a situation, the complainant who has preferred an appeal under Section 378 CrPC dies, what would be the fate of the appeal is not a question which arises in this case and therefore, we keep the said question open to be adjudicated in any other appropriate case.

12. In the circumstances, the delay in filing the application for seeking setting aside of the abatement is condoned. The abatement is set aside. The application for substitution of applicant is allowed. Consequently, the applicant is permitted to be brought on record as the legal representative of the original appellant, apart from he being an injured victim also. Appellant’s counsel to file amended memo of parties.

CRIMINAL APPEAL NOS.1330-1332 OF 2017:

1. The appellant herein, who is the legal heir of the original appellant (and a victim of the incident that occurred on 09.12.1992) has been substituted to prosecute these appeals which have been filed being aggrieved by the judgment of acquittal of the accused vide order dated 12.09.2012 passed in Criminal Appeal Nos.254 of 2004, 258 of 2004, 259 of 2004 by the High Court of Uttarakhand at Nainital.

2. Learned counsel for the appellant made a two-fold submission: firstly, he contended that even without going into the merits of the case, the manner and tenor of the judgment may be considered; that this is a judgment of a High Court which was considering a first appeal against a judgment and order of conviction which appeals were filed by respondents – accused; that in a cryptic manner, the judgment has been delivered by the High Court acquitting the respondents – accused. That this Court in a catena of cases has observed that even if a judgment confirming the judgment of a Sessions Court is to be rendered by the High court and thereby dismissing the first appeal which has been preferred under Section 374 CrPC, the appeal would have to be considered based on the evidence on record and thereafter possibly the High Court could dismiss such an appeal. But here is a case where the High Court has reversed the judgment of the Sessions Court inasmuch as the judgment and sentence of life imprisonment has been set aside and a complete acquittal given to the respondents – accused without there being any reasons and marshalling of the facts and the evidence on record. In this regard, he drew our attention to paragraph 7 of the impugned judgment and submitted that the findings in paragraph 7 of the impugned judgment are de hors any basis in the absence of there being a discussion of the facts and evidence on record. In the circumstances, he submitted that this Court if it is so inclined may consider remanding of the matter without going into the merits of the case.

3. The second submission of learned counsel for the appellant is, in the event this Court is not inclined to accept the first submission, then the appeal can be taken up on merits. Learned counsel submitted that even on merits, the High Court could not have given a judgment of acquittal by reversing the judgment of the Sessions Court. He therefore submitted that the impugned judgment may be set aside and the judgment of the Sessions Court may be restored.

4. Per contra, learned senior counsel and learned counsel appearing for the respondents-accused who have been acquitted, vehemently contended that there is no merit in the submissions made by appellant’s counsel. They drew our attention to the fact that the High Court may have given the judgment pithily but it is not without substance. Merely because the impugned judgment is short and not lengthy cannot make it an erroneous judgment so long as the reasoning is evident and there is a basis for the findings arrived In the circumstances, this Court may not accept the first contention of the appellant and hence, they contended that they are ready to argue the matter on merits so that this Court could confirm the judgment of acquittal passed by the High Court.

5. Learned counsel for the respondent-State submitted that, no doubt the State has not preferred an appeal against the judgment of acquittal as against the respondents – accused before this However, the State had preferred an appeal against the acquittal of six other accused and that appeal was dismissed but in these appeals filed by the appellant herein, the State is supporting the appellant. Learned counsel for the respondent – State submitted that having regard to the submissions advanced by the respective counsel and learned counsel for the parties, this Court may consider remanding the matter to the High Court so that all parties would get an opportunity to put forth their respective cases and the High Court could consider the appeal afresh and in accordance with law and come to its conclusion.

6. While hearing the appeals under Section 374(2) of the CrPC, the High Court is exercising its appellate There shall be independent application of mind in deciding the criminal appeal against conviction. It is the duty of an appellate court to independently evaluate the evidence presented and determine whether such evidence is credible. Even if the evidence is deemed reliable, the High Court must further assess whether the prosecution has established its case beyond reasonable doubt. The High Court though being an appellate Court is akin to a Trial Court, must be convinced beyond all reasonable doubt that the prosecution’s case is substantially true and that the guilt of the accused has been conclusively proven while considering an appeal against a conviction.

As the first appellate court, the High Court is expected to evaluate the evidence including the medical evidence, statement of the victim, statements of the witnesses and the defence version with due care.

7. While the judgment need not be excessively lengthy, it must reflect a proper application of mind to crucial evidence. Albeit the High Court does not have the advantage to examine the witnesses directly, the High Court should, as an appellate Court, re-assess the facts, evidence on record and findings to arrive at a just conclusion in deciding whether the Trial Court was justified in convicting the accused or not. We are also cognizant of the large pendency of cases bombarding our courts. However, the same cannot come in the way of the Court’s solemn duty, particularly, when a person’s liberty is at stake.

8. This Court in State of Uttar Pradesh vs. Ambarish, (2021) 16 SCC 371 held that while deciding a criminal appeal on merits, the High Court is required to apply its mind to the entirety of the case including the evidence on the record before arriving at its conclusion. In this regard, we may also refer to the orders passed by this Court in Shakuntala Shukla State of Uttar Pradesh, (2021) 20 SCC 818 and State Bank of India vs. Ajay Kumar Sood, (2023) 7 SCC 282.

9. We find that the High Court ought to have considered the evidence on record in light of the arguments advanced at the bar and thereafter ascertained whether the Sessions Court was justified in passing the judgment of conviction and imposing the sentence. The same being absent in the impugned judgment, for that sole reason, we set aside the same.

10. We therefore find that the first contention advanced by the learned counsel for the appellant and the submission made by learned counsel for the respondent-State has to be accepted for the reason that the respondents-accused in these appeals respectively would also have another opportunity in the appeals that they had filed before the High Court. In the circumstances, while holding that the impugned judgment of the High Court is cryptic and de hors any reasoning in coming to the findings in paragraph 7 of the said judgment, we set aside the said judgment without expressing anything on the merits of the case.

11. We allow the appeals filed on the aforesaid limited grounds.

12. The matters are remanded to the High Court of Uttarakhand at Nainital.

13. The High Court is requested to rehear the appeals filed by the respondents/accused respectively in these appeals by also giving an opportunity to the appellant herein to make his submission in the said appeals as well as the State to make its submission in the matter.

14. We once again clarify that we have not made any observations on the merits of the matter.

15. All contentions on both sides are left open to be advanced before the High Court.

16. Since the incident is of the year 1992 and the impugned order is dated 12.09.2012 and we are remanding the matter to the High Court, we request the High Court to dispose of the appeal as expeditiously as possible.

17. Since we have set aside the judgment dated 12.09.2012 passed by the High Court of Uttarakhand at Nainital in Criminal Appeal Nos.254 of 2004, 258 of 2004, 259 of 2004, the accused Nos.4, 3 and 2 respectively shall remain on However, accused Nos.4, 3 and 2 shall appear before the concerned Principal District and Sessions Judge, Haridwar and execute fresh bonds for a sum of Rs.15,000/- each with two like sureties each and subject to other conditions imposed by the concerned Principal District and Sessions Judge, Haridwar.

These appeals are allowed and disposed of in the aforesaid terms.