Teachers’ Eligibility Test Mandatory to Continue in Service

Anjuman Ishaat-e-Taleem Trust v The State of Maharastra & Ors.

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that teachers with more than five years of service remaining must clear the Teacher Eligibility Test (TET) to continue in their jobs. It referred to a larger Bench the question of whether the Right to Education Act, 2009 (RTE Act), applies to Minority Educational Institutions (MEI).

Anjuman...

Case Details

Judgement Date: 1 September 2025

Citations: 2025 INSC 1063 | 2025 SCO.LR 9(2)[7]

Bench: Dipankar Datta J, Manmohan J

Keyphrases: Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009—Section 23—Teacher Eligibility Test (TET)—In-service teachers with more than 5 years to superannuation must qualify TET within two years to continue in service—Whether Minority Educational Institutions should comply with RTE Act referred to a larger Bench—Section 12(1)(c) of RTE Act—minority rights under Article 30

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

DIPANKAR DATTA, J.

I. Introduction

1. These civil appeals challenge judgments/orders of two of the three chartered high courts of the nation delivered/made on multiple

proceedings instituted before them. Inter alia, questions as regards applicability of the Teacher Eligibility Test1 to minority educational institutions and whether qualifying in the TET is a mandatory prerequisite for recruitment of teachers as well as promotion of teachers already in service, were under consideration in such proceedings. In brief, the appellants before this Court are:

a. Minority educational institutions who are aggrieved because they are not being allowed to recruit teachers who have not qualified in the TET;

b. Authorities within the meaning of Article 12 of the Constitution claiming that qualifying the TET is a mandatory requirement for appointment of teachers not only in non-minority but also minority institutions, whether aided or unaided; and

c. Individual teachers, who were appointed prior to the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 20092 being enforced, claiming that the TET qualification cannot be made a mandatory requirement for the purposes of their promotion.

2. The present set of appeals raise questions of seminal importance. Vide order dated 28th January, 2025 in the erstwhile lead matter, viz. Civil Appeal No.1384 of 20253, the issues for consideration were framed by us. The said appeal came to be disposed of as withdrawn along with certain other appeals, vide order dated 20th February 2025, as the appellant(s) did not wish to pursue the appeals any further; however, the remaining tagged appeals were heard and subsequently reserved for judgment (with the lead matter now being Civil Appeal No. 1385 of 2025).

3. Two broad issues arising for consideration were noted in the order dated 28th January, 2025. The first issue was framed by a coordinate Bench vide order dated 14th February, 2022 in B. Annie Packiarani Bai (supra) whereas the other was framed by us, upon hearing counsel for the parties who had the occasion to address the Court on 28th January, 2025. The issues, as recast, read as under:

a. Whether the State can insist that a teacher seeking appointment in a minority educational institution must qualify the TET? If so, whether providing such a qualification would affect any of the rights of the minority institutions guaranteed under the Constitution of India?

and

b. Whether teachers appointed much prior to issuance of Notification No.61-1/2011/NCTE (N & S) dated 29th July, 2011 by the National Council for Teacher Education4 under sub-section (1) of Section 23 of the RTE Act read with the newly inserted proviso (second proviso) in Section 23(2) and having years of teaching experience (say, 25 to 30 years) are required to qualify in the TET for being considered eligible for promotion?

II. ORDERS PASSED BY THE RESPECTIVE HIGH COURTS, IMPUGNED IN THE APPEALS

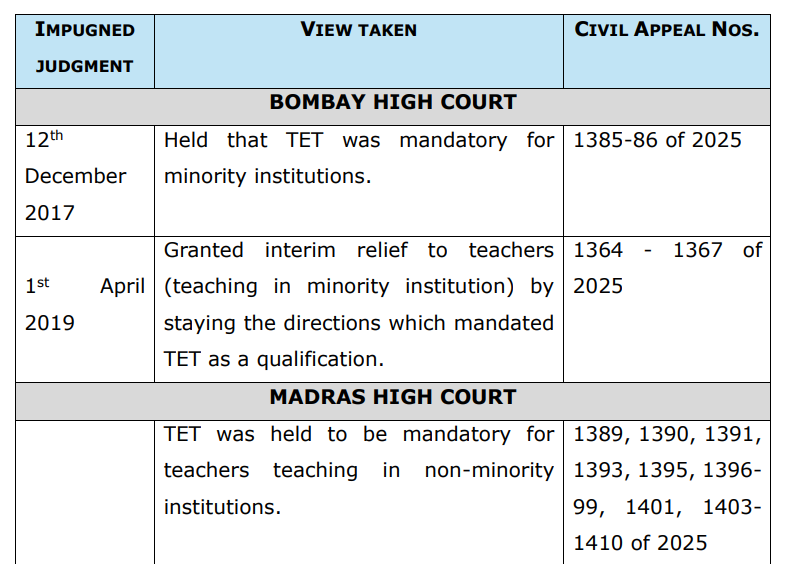

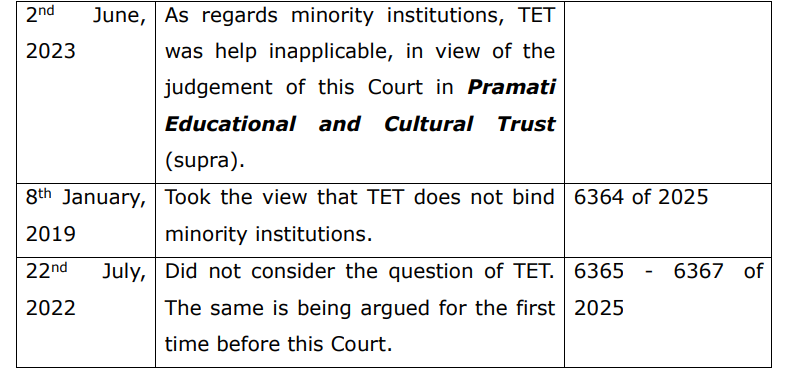

4. At the outset, we consider it appropriate to give a brief outline of the judgments/orders under challenge in the present surviving set of appeals.

IMPUGNED JUDGMENT IN THE LEAD APPEAL BEING CIVIL APPEAL NO. 1385 OF 2025 AND CIVIL APPEAL NO. 1386 OF 2025

5. The judgment impugned in the lead appeal is that of the High Court of Judicature at Bombay5 dated 12th December 2017 on a writ petition6 instituted by Azad Education Society, Miraj (a minority institution). Under challenge was a Government Resolution dated 23rd August, 2013, by which the TET qualification was made a pre-condition for appointment of teachers in schools imparting primary education by the Government of Maharashtra. The Bombay High Court considered the validity of such resolution and upheld it relying on the decision of this Court in Ahmedabad St. Xavier’s College Society v. State of Gujarat7. It was held that the impugned Government Resolution did not put any embargo on the right of the minority institutions to appoint teachers of their own choice, if found eligible being a TET qualified candidate. The writ petition, thus, came to be dismissed by the impugned order. Azad Education Society, Miraj has not preferred any appeal against the said judgment.

6. The appellant, Anjuman Ishaat-e-Taleem Trust (a recognised minority education society), was not a party to the writ petition instituted by Azad Education Society, Miraj before the Bombay High Court. It sought permission to file the special leave petition against the said judgment, which was granted. Its appeal is Civil Appeal No. 1385 of 2025.

7. The same judgment has also been impugned by the appellant, Association of Urdu Education Societies (an association managing minority educational institutions), in Civil Appeal No. 1386 of 2025 in the same manner upon being granted permission to file the special leave petition.

8. It has been argued that this judgment (dated 12th December 2017) failed to consider a judgment of a co-ordinate bench of the Bombay High Court8 which took a contrary view.

IMPUGNED JUDGMENT IN CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 6365 – 6367 OF 2025

9. The impugned judgment in these civil appeals has been passed by the High Court of Judicature at Madras9, whereby the writ appeals10 filed by the appellants therein, i.e., the State of Tamil Nadu and officers in the State’s Education Department, came to be dismissed.

10. The writ petitions11 were filed by the Management of Islamiah Higher Secondary Schools (respondent herein, being a minority institution), challenging the rejection of their proposal for appointment of teachers. The District Educational Officer denied the proposal for appointment observing that surplus/excess staff under the same management must be exhausted fully before making fresh appointments.

11. A Single Judge of the High Court vide order dated 7th December, 2021, allowed the writ petition by setting aside the rejection of the proposal and held that the respondent, as a standalone institution, was not bound by the rule of recruiting surplus staff under the same management.

12. The writ appeal against the order of the Single Judge came to be dismissed by a Division Bench of the High Court vide judgment and order dated 22nd July, 2022, which is impugned in these appeals by the State of Tamil Nadu and its officers.

13. Interestingly, the argument regarding the TET qualification was not raised before the Madras High Court and is being raised for the first time in the present appeal. The State of Tamil Nadu has contended that the teachers sought to be appointed did not possess the TET qualification and hence, their proposal for appointment should be rejected on that ground alone.

Impugned Order in Civil Appeal Nos. 1364 – 1367 of 2025

14. The common order under challenge in these appeals, dated 1st April 2019, was passed by the Bombay High Court on four writ petitions12 . Interim relief was granted thereby in favour of the writ petitioners.

15. In 2015, the Bombay Memon’s Education Society, a registered minority society, had appointed Shikshan Sevaks/teachers for a school run by it, viz. Shree Ram Welfare Society’s High School. In 2018, the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai13, through its Education Department informed these teachers of the requirement to qualify the TET by 30th March, 2019 and directed the school to terminate the services of those who failed to comply.

16. Challenging these directions, the affected teachers filed the said four writ petitions. The Bombay High Court granted interim stay on the MCGM’s directives and also directed that the salaries of the teachers be released. Aggrieved thereby, the MCGM has preferred the present

IMPUGNED JUDGMENT IN CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 1389, 1390, 1391, 1393, 1395,1396, 1397, 1398, 1399, 1401, 1403, 1404, 1405, 1406, 1407, 1408, 1409, 1410 OF 2025

17. The common judgment dated 2nd June, 2023 under challenge in these appeals was passed by the Madras High Court in its intra-court writ appeal jurisdiction. Several individual teachers working in minority as well as non-minority schools in Tamil Nadu petitioned the Madras High Court aggrieved by Notification No.61-03/20/2010/NCTE/(N&S) dated 23rd August, 2010 issued by the NCTE which laid down minimum qualification for appointment of teachers in classes I to VIII in a school and also made the TET as the minimum qualification. By notification dated 29th July, 2011, certain amendments were made to the first notification, without changing the requirement to qualify the TET. Pursuant to the NCTE notifications, the Government of Tamil Nadu, through its School Education (C2) Department, issued G.O. No.181 making the TET qualification mandatory for the State, to be conducted by the Teachers Recruitment Board (TRB). These notifications along with subsequent others, laying down the procedure for conduct of the TET, were challenged before the Madras High Court.

18. The primary grievance of the petitioners — who had not cleared the TET— was that they were being denied promotion, whilst the teachers who possessed the TET had climbed the promotion ladder and were holding higher posts. The petitioners, having been appointed prior to the notification dated 23rd August, 2010, contended that they were not required to possess the TET qualification either for promotion or for continued service. According to them, the TET could not be treated as a condition precedent for their continuation in service.

19. On the other hand, a separate batch of petitioners had approached the Madras High Court seeking a declaration that a G.O. Ms. No.13 issued by the School Education Department on 30th January, 2020, framing Special Rules for the Tamil Nadu Elementary Education Subordinate Service and restricting the requirement of the TET to direct recruitment, was ultra vires the RTE Act and subsequent notifications issued thereunder by the It was contended that in-service candidates who did not possess the TET qualification could not be conferred promotion.

20. Several teachers, who had been promoted without possessing the TET qualification, also approached the Madras High Court by way of separate petitions, seeking the grant of annual increments on account of their promotions.

21. Upon extensive analysis of the submissions and considering the relevant law, the Madras High Court held that any teacher appointed as secondary grade teacher or graduate teacher/BT Assistant prior to 29th July, 2011 could continue in service and receive increments and incentives, however, it was mandatory for teachers aspiring for promotion to possess the TET qualification. The Court further held that all appointments made after 29th July, 2011 on the post of Secondary Grade Teacher must be of candidates possessing the TET qualification. Likewise, all appointments on the posts of BT Assistant/Graduate Teacher made after 29th July, 2011 – whether by direct recruitment or by promotion – must also meet the TET requirement.

22. The Special Rules for the Tamil Nadu School Educational Subordinate Service, dated 30th January, 2020, insofar as they prescribed “a pass in Teacher Eligibility Test (TET)” only for direct recruitment and not for promotion were struck down, consequently holding the TET mandatory for appointment even by promotion.

23. As regards the requirement of qualifying the TET for appointment of teachers in minority institutions, the Court referred to the decision of this Court in Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust v. Union of India 14 which held that TET will not apply to minority institutions. It was made clear that the principles laid down in the judgment would not apply to minority institutions (whether aided or unaided).

Impugned judgment in Civil Appeal No. 6364 of 2025

24. This appeal, at the instance of the Union of India15, arises from the judgment and order dated 8th January, 2019 passed by the Madras High Court in its intra-court appellate jurisdiction dismissing the writ appeal16filed by the State of Tamil As a consequence thereof, the order of the Single Judge (under appeal allowing the writ petition17 filed by M.A. Stephen Sundar Singh18, respondent no.1 herein, was upheld. UoI was not a party to the writ petition before the Madras High Court, but has carried the said judgment in this civil appeal upon being granted permission to file the Special Leave Petition.

25. Stephen was appointed as a Secondary Grade Teacher in TDTA Primary and Middle School19– an aided minority The appointment of Stephen was communicated by the school to the District Elementary Education Officer20, for confirmation. The DEEO, however, refused to approve the appointment on the ground that Stephen had not qualified the TET. Aggrieved by the rejection, Stephen filed the writ petition, which was allowed by the High Court vide order dated 28th April, 2018.

26. A Division Bench of the High Court upheld the said judgment and order dated 8th January, 2019 in light of Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra), consistent with the view that the RTE Act does not bind minority Consequently, Stephen was held not to be required to have cleared the TET, and the DEEO was directed to approve his appointment.

27. Aggrieved, UoI has approached this Court.

Summary of the judgments

28. A brief summary of the views taken by the Bombay and the Madras High Courts vide different judgments is encapsulated below:

III.Previous decisions concerning the RTE Act

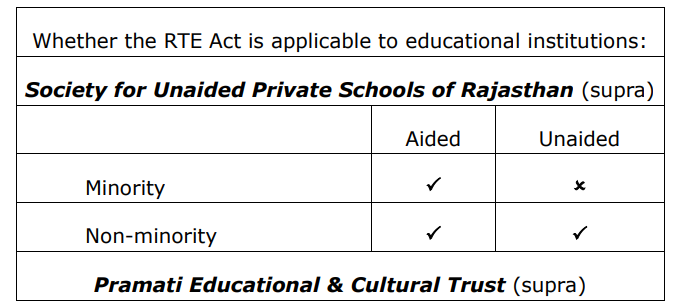

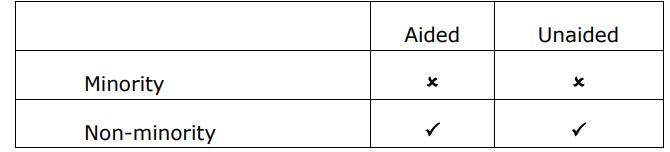

Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan

29. A three-Judge Bench had the occasion to consider a challenge to the constitutionality of the RTE Act, specifically to Sections 3, 12(1)(b) and 12(1)(c) thereof, in P. 95 of 2010 (Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan v. Union of India) and other connected writ petitions. Vide order dated 6th September, 201021, the Bench of three-Judges had referred the matter to a larger Bench. The reference order reads thus:

“1. Since the challenge involved raises the question as to the validity of Articles 15(5) and 21-A of the Constitution of India, we are of the view that the matter needs to be referred to the Constitution Bench of five Judges.

2. Issue rule The learned Solicitor General waives service of the rule. All the respondents are before us. The counter-affidavits be filed within four weeks.

3. These petitions be placed before the Constitution Bench for directions on a suitable date.”

30. However, despite the aforesaid reference, the same remained unanswered. The three-Judge Bench then proceeded to hear and dispose of the matter by a majority of 2:1 vide its judgment in Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan v. Union of India22.

31. The issue in Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan (supra) is well encapsulated at paragraph 69 of the minority judgment, reading thus:

“69.………………. Controversy in all these cases is not with regard to the validity of Article 21-A, but mainly centres around its interpretation and the validity of Sections 3, 12(1)(b) and 12(1)(c) and some other related provisions of the Act, which cast obligation on all elementary educational institutions to admit children of the age 6 to 14 years from their neighbourhood, on the principle of social inclusiveness. The petitioners also challenge certain other provisions purported to interfere with the administration, management and functioning of those institutions.”

32. The issues so framed were approved by the majority, as it appears from the following passage:

“2. The judgment of *** fully sets out the various provisions of the RTE Act as well as the issues which arise for determination, the core issue concerns the constitutional validity of the RTE Act.”

33. Section 3 of the RTE Act affirms the right of a child between 6 and 14 years of age, to receive free and compulsory elementary education in a neighbourhood Section 12(1)(c) read with Sections 2(n)(iii) and (iv) imposes an obligation on unaided private educational institutions, both minority and non-minority, to admit in Class I (and in pre-school, if available) at least 25% of their strength from among children covered under Sections 2(d) and 2(e). Section 12(1)(b) read with Sections 2(n)(ii) provides imposes a similar obligation on aided private educational institutions.

34. Per curiam, challenge to the constitutionality of most of the provisions of the RTE Act was rejected. However, difference of opinion arose as to the applicability of the RTE Act to unaided minority and unaided non- minority educational institutions.

35. The minority view held that the RTE Act was not applicable to any unaided educational institution – whether minority or non-minority – as it infringed their Fundamental Rights under Articles 19(1)(g) and 30(1) of the Constitution.

36. The minority also took the view that the obligation under Section 12 (1)(c) cannot be cast on unaided private institutions, whether minority or non-minority. It was emphasized that private citizens running a private school, receiving no aid from the State, have no constitutional duty to assume the welfare responsibilities of the State. Citing the decisions of this Court in M.A. Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka23 and P. A. Inamdar v. State of Maharashtra24, the learned Judge concluded that compulsory seat-sharing and fee regulation by the State constituted an unjust encroachment on the autonomy of such institutions and their Fundamental Rights under Articles 19(1)(g) and 30(1). Furthermore, it was held, as regards unaided institutions (whether minority or non-minority), that Section 12(1)(c) can be implemented only on the basis of voluntariness and consensus, as otherwise, it may violate the autonomy of such institutions. Accordingly, Section 12(1)(c) was read down as being merely directory qua all unaided educational institutions (minority and non-minority).

37. The majority, while agreeing that the RTE Act could not be applied to unaided minority institutions in view of the protection under Article 30(1), held that the RTE Act, particularly the obligation imposed by Section 12(1)(c), was applicable to aided minority institutions. The majority reasoned that such a provision constituted a reasonable restriction on the Fundamental Right under Article 19(1)(g), permissible under Article 19(6).

38. The majority further held that Section 12(1)(c) meets the test of reasonable classification under Article 14 of the Constitution and constitutes a reasonable restriction on the right to establish and administer educational institutions under Article 19(1)(g). Inter alia, the court: (i) observed that Article 21-A left it for the State to determine by law how the obligation of providing free and compulsory education may be fulfilled; (ii) emphasized that the Fundamental Rights must be interpreted in conjunction with the Directive Principles of State Policy, and that any law which limits Fundamental Rights within the limits justified by the Directive Principles can be upheld as a “reasonable restriction” under Articles 19(2) to 19(6); (iii) underscored that since education is a charitable activity (and not commercial), imposing an obligation on educational institutions under Section 12(1)(c) constitutes a reasonable restriction on their Fundamental Right under Article 19(1)(g),which is a qualified right; (iv) further traced that Section 12(1)(c) is a reasonable restriction as it advances the State’s obligation to provide education; (v) clarified that the RTE Act does not override the rights recognized in T.M.A. Pai Foundation (supra) and P. A. Inamdar (supra), as those decisions pertained to higher/professional education and did not address the interpretation of Article 21-A or the provisions of the RTE Act.

Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust v. Union of India

39. While the matter stood thus, W.P. (C) No. 416 of 2012 (Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust v. Union of India) came up for consideration before a Bench of two-judges. This Bench comprised of a learned Judge who was a member of the three-Judge Bench that had decided Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan (supra). Incidentally, the three-Judge Bench had proceeded to decide Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan (supra) despite there being an earlier order of reference to a Constitution Bench [noted in paragraph 9 (supra)]. In view of such earlier reference of the issues to a Constitution Bench [noted in paragraph 9 (supra)], the said Bench vide its order dated 22nd March, 201325 was of the opinion that the matter ought to be heard by a larger Bench and, accordingly, directed that the same be placed before the Hon’ble the Chief Justice of India for its listing before an appropriate bench. Thus, the lead writ petition and the accompanying petitions came to be heard by a five-Judge Constitution Bench of this Court leading to the judgment in Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra).

40. Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra) considered the validity of the Constitution (Ninety-third Amendment) Act, 2005 inserting clause (5) in Article 15 of the Constitution, and the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, which inserted Article 21-A in Part III as an additional independent fundamental right.

41. The Constitution Bench in Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra) framed specific questions for consideration, as under:

“(i) Whether by inserting clause (5) in Article 15 of the Constitution by the Constitution (Ninety-third Amendment) Act, 2005, Parliament has altered the basic structure or framework of the Constitution?

(ii) Whether by inserting Article 21-A of the Constitution by the Constitution (Eighty-Sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, Parliament has altered the basic structure or framework of the Constitution?”

42. Notably, the validity of the Constitution (Ninety-third Amendment) Act, 2005, which inserted clause (5) in Article 15, had been considered by a Constitution Bench of this Court in Ashoka Kumar Thakur Union of India26 to the limited extent of its application to state-maintained institutions and aided educational institutions. Relevant passages from the decision in Ashoka Kumar Thakur (supra) read as under:

“668. The Constitution 93rd Amendment Act, 2005, is valid and does not violate the “basic structure” of the Constitution so far as it relates to the State maintained institutions and aided educational institutions. Question whether the Constitution (Ninety Third Amendment) Act, 2005 would be constitutionally valid or not so far as ‘private unaided’ educational institutions is concerned, is not considered and left open to be decided in an appropriate case. Justice***, in his opinion, has, however, considered the issue and has held that the Constitution (Ninety Third Amendment) Act, 2005 is not constitutionally valid so far as private un-aided educational institutions are concerned.

669. Act 5 of 2007 is constitutionally valid subject to the definition of ’Other Backward Classes’ in Section 2(g) of the Act 5 of 2007 being clarified as follows: If the determination of ’Other Backward Classes’ by the Central 2 Government is with reference to a caste, it shall exclude the ’creamy layer’ among such caste.

670. Quantum of reservation of 27% of seats to Other Backward Classes in the educational institutions provided in the Act is not illegal.

671. Act 5 of 2007 is not invalid for the reason that there is no time limit prescribed for its operation but majority of the Judges are of the view that the Review should be made as to the need for continuance of reservation at the end of 5 years.”

(emphasis ours)

Therefore, effectively, what remained to be considered, qua issue no.(i) in Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra) was, whether the amendment inserting clause 5 in Article 15 is valid or not, insofar as private unaided instructions are concerned.

43. To ascertain the constitutionality of the Constitution (Ninety-third Amendment) Act, 2005, the Bench considered the objects and reasons of the Act and opined that the insertion of clause (5) to Article 15 is an enabling provision. It observed that the amendment was brought forth to fructify the object of equality of opportunity provided in the Preamble to the The court relied on the judgment of State of Kerala v. N.M. Thomas27 which held that clause (4) of Article 16 of the Constitution is not an exception or a proviso to Article 16. Drawing an inference, it was observed that the opening words of clause (5) of Article 15 are similar to the opening words of clause (4) of Article 16 and thus held that Article 15(5) cannot be read as an exception to Article 15, but is an enabling provision intended to give equality of opportunity to backward classes of citizens in matters of public employment.

44. The validity of clause (5) of Article 15 of the Constitution was then tested against the right enshrined under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution and the court held as thus:

“28. …………………………. In our view, all freedoms under which Article 19(1) of the Constitution, including the freedom under Article 19(1)(g), have a voluntary element but this voluntariness in all the freedoms in Article 19(1) of the Constitution can be subjected to reasonable restrictions imposed by the State by law under clauses (2) to (6) of Article 19 of the Constitution. Hence, the voluntary nature of the right under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution can be subjected to reasonable restrictions imposed by the State by law under clause (6) of Article 19 of the Constitution. As this Court has held in T.M.A. Pai Foundation [T.M.A. Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka, (2002) 8 SCC 481] and P.A. Inamdar [P.A. Inamdar v. State of Maharashtra, (2005) 6 SCC 537] the State can under clause (6) of Article 19 make regulatory provisions to ensure the maintenance of proper academic standards, atmosphere and infrastructure (including qualified staff) and the prevention of maladministration by those in charge of the management. However, as this Court held in the aforesaid two judgments that nominating students for admissions would be an unacceptable restriction in clause (6) of Article 19 of the Constitution, Parliament has stepped in and in exercise of its amending power under Article 368 of the Constitution inserted clause (5) in Article 15 to enable the State to make a law making special provisions for admission of socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes for their advancement and to a very limited extent affected the voluntary element of this right under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution. We, therefore, do not find any merit in the submission of the learned counsel for the petitioners that the identity of the right of unaided private educational institutions under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution has been destroyed by clause (5) of Article 15 of the Constitution.”

45. The Court further observed that clause (5) of article 15, which excluded the application of Article 19(1)(g), was constitutional and would not be in violation of the decisions of this court in M.A. Pai Foundation (supra), as subsequently followed in P. A. Inamdar (supra). Thus, on this count as well, it was held that the exception provided in clause (5) of Article 15 was reasonable, and as such this court upheld the validity of Constitution (Ninety-third Amendment) Act, 2005, inserting clause (5) of Article 15.

46. The Bench then considered the validity of the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002.

47. It was noticed that the majority in Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan (supra) had upheld the constitutionality of the RTE Act with a caveat that it would be inapplicable to unaided minority institutions. In that context, it was observed thus:

“4. Article 21-A of the Constitution reads as follows:

21-A.Right to education.—The State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of six to fourteen years in such manner as the State may, by law, determine.’

Thus, Article 21-A of the Constitution, provides that the State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of six to fourteen years in such manner as the State may, by law, determine. Parliament has made the law contemplated by Article 21- A by enacting the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009 (for short “the RTE Act”). The constitutional validity of the RTE Act was considered by a three-Judge Bench of the Court in Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan v. Union of India [(2012) 6 SCC 1]. Two of the three Judges have held the RTE Act to be constitutionally valid, but they have also held that the RTE Act is not applicable to unaided minority schools protected under Article 30(1) of the Constitution. In the aforesaid case, however, the three-Judge Bench did not go into the question whether clause (5) of Article 15 or Article 21-A of the Constitution is valid and does not violate the basic structure of the Constitution. In this batch of writ petitions filed by the private unaided institutions, the constitutional validity of clause (5) of Article 15 and of Article 21-A has to be decided by this Constitution Bench.”

(emphasis ours)

48. The validity of the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, which inserted Article 21A to the Constitution of India, was considered on the anvil of the basic structure doctrine as expounded in the landmark decision of this Court in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala28. Answering the issue in the negative, the Bench held that Parliament was within its bounds to insert Article 21-A and as such, the amendment would not be in violation of the basic structure doctrine.

49. Thereafter, the Court considered the objects and reasons of the Constitution (Eighty-third Amendment) Bill, 1997, which ultimately resulted in the enactment of the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, and observed that the amendment was brought in force to satisfy the obligation under Article 45 of the Indian Constitution. The Bench, upon extracting the objects and reasons, opined thus:

“48. …It will, thus, be clear from the Statement of Objects and Reasons extracted above that although the directive principle in Article 45 contemplated that the State will provide free and compulsory education for all children up to the age of fourteen years within ten years of promulgation of the Constitution, this goal could not be achieved even after 50 years and, therefore, a constitutional amendment was proposed to insert Article 21-A in Part III of the Constitution. Bearing in mind this object of the Constitution (Eighty- sixth Amendment) Act, 2002 inserting Article 21-A of the Constitution, we may now proceed to consider the submissions of the learned counsel for the parties.”

50. Interpreting the word ‘State’ in Article 21A, it was held that ‘State’ would mean the State which can make the law. This, the Bench held, was the dicta of the 11-judge Constitution Bench of this Court in M.A. Pai Foundation (supra). It was held that Article 21A must be construed harmoniously with Article 19(1)(g) and Article 30(1). It then proceeded to observe as follows:

“49. Article 21-A of the Constitution, as we have noticed, states that the State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of six to fourteen years in such manner as the State may, by law, determine. The word ‘State’ in Article 21-A can only mean the ‘State’ which can make the law. Hence, Mr Rohatgi and Mr Nariman are right in their submission that the constitutional obligation under Article 21-A of the Constitution is on the State to provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of 6 to 14 years and not on private unaided educational institutions. Article 21-A, however, states that the State shall by law determine the ‘manner’ in which it will discharge its constitutional obligation under Article 21-A. Thus, a new power was vested in the State to enable the State to discharge this constitutional obligation by making a law. However, Article 21-A has to be harmoniously construed with Article 19(1)(g) and Article 30(1) of the Constitution. As has been held by this Court in Venkataramana Devaru v. State of Mysore [AIR 1958 SC 255]: (AIR p. 268, para 29)

‘29. … The rule of construction is well settled that when there are in an enactment two provisions which cannot be reconciled with each other, they should be so interpreted that, if possible, effect could be given to both. This is what is known as the rule of harmonious construction.’

We do not find anything in Article 21-A which conflicts with either the right of private unaided schools under Article 19(1)(g) or the right of minority schools under Article 30(1) of the Constitution, but the law made under Article 21-A may affect these rights under Articles 19(1)(g) and 30(1). The law made by the State to provide free and compulsory education to the children of the age of 6 to 14 years should not, therefore, be such as to abrogate the right of unaided private educational schools under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution or the right of the minority schools, aided or unaided, under Article 30(1) of the Constitution.”

51. Thus, this Court upheld the validity of the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, and proceeded to hold that the RTE Act, insofar it is made applicable to minority schools referred to in Article 30(1), is ultra vires the Constitution of India. While overruling the decision in Society of Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan (supra) insofar as it held that the RTE Act was applicable to aided minority schools, it was further held that the RTE Act, insofar as it is made applicable to minority schools covered under Article 30(1), aided or unaided, is ultra vires the Constitution. It was concluded thus:

“55. When we look at the RTE Act, we find that Section 12(1)(b) read with Section 2(n)(ii) provides that an aided school receiving aid and grants, whole or part, of its expenses from the appropriate Government or the local authority has to provide free and compulsory education to such proportion of children admitted therein as its annual recurring aid or grants so received bears to its annual recurring expenses, subject to a minimum of twenty-five per cent. Thus, a minority aided school is put under a legal obligation to provide free and compulsory elementary education to children who need not be children of members of the minority community which has established the school. We also find that under Section 12(1)(c) read with Section 2(n)(iv), an unaided school has to admit into twenty- five per cent of the strength of Class I children belonging to weaker sections and disadvantaged groups in the neighbourhood. Hence, unaided minority schools will have a legal obligation to admit children belonging to weaker sections and disadvantaged groups in the neighbourhood who need not be children of the members of the minority community which has established the school. While discussing the validity of clause (5) of Article 15 of the Constitution, we have held that members of communities other than the minority community which has established the school cannot be forced upon a minority institution because that may destroy the minority character of the school. In our view, if the RTE Act is made applicable to minority schools, aided or unaided, the right of the minorities under Article 30(1) of the Constitution will be abrogated. Therefore, the RTE Act insofar it is made applicable to minority schools referred in clause (1) of Article 30 of the Constitution is ultra vires the Constitution. We are thus of the view that the majority judgment of this Court in Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan v. Union of India [(2012) 6 SCC 1] insofar as it holds that the RTE Act is applicable to aided minority schools is not correct.

56. In the result, we hold that the Constitution (Ninety-third Amendment) Act, 2005 inserting clause (5) of Article 15 of the Constitution and the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002 inserting Article 21-A of the Constitution do not alter the basic structure or framework of the Constitution and are constitutionally valid. We also hold that the RTE Act is not ultra vires Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution. We, however, hold that the RTE Act insofar as it applies to minority schools, aided or unaided, covered under clause (1) of Article 30 of the Constitution is ultra vires the Constitution. Accordingly, Writ Petition (C) No. 1081 of 2013 filed on behalf of Muslim Minority Schools Managers’ Association is allowed and Writ Petitions (C) Nos. 416 of 2012, 152 of 2013, 60, 95, 106, 128, 144-45, 160 and 136 of 2014 filed on behalf of non-minority private unaided educational institutions are dismissed. All IAs stand disposed of. The parties, however, shall bear their own costs.”

(emphasis ours)

For ease of reference, the decisions of this Court in so far as the applicability of the RTE Act, considered in Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan (supra) and Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra), are encapsulated in the table below:

IV. Arguments of the Parties

52. Learned senior counsel and counsel for the respective parties were heard at length. We also requested Mr. Venkatramani, learned Attorney General for India to address us on the issue and to assist us in reaching the correct conclusion.

53. Accordingly, in support of the issues that Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra) may be referred for reconsideration and also that qualifying the TET is mandatory, we have heard the learned Attorney General, Nataraj, learned Additional Solicitor General, and a host of other senior advocates and advocates, in favour as well as opposing the prayer for a reference and the TET being mandatory, referred to above.

54. In order to maintain brevity and avoid repetition of the arguments by counsel, a summary of the submissions on either side is provided hereafter.

55. Those opposing reconsideration contended that:

a. There is no State legislation in place making the TET as mandatory for appointment of teachers in the State of Maharashtra.

b. Strict TET requirement amid low pass rates and rising teacher demand will lead to shortage of teachers which will undermine the objectives of the RTE Act.

c. Law made in exercise of the mandate of Article 21A should not abrogate the rights of minority educational institutions under Article 30(1) of the Constitution.

d. Section 1(4) of the RTE Act itself provides that the provisions of the RTE Act are subject to Articles 29 and 30 of the Constitution – hence RTE Act is not applicable to minority institutions.

e. TET is not a ‘minimum qualification’ under Section 23 of the RTE Act, but it is merely an eligibility test to assess teaching aptitude and should not be equated with a minimum qualification.

f. The phrase ‘appointment as a teacher’ under Section 23 of the RTE Act should be read to mean ‘initial appointment as a teacher’ and would not include appointment by promotion to any grades subsequently and hence it is sufficient that the teacher concerned has necessary minimum qualification at the time of first appointment.

g. In Section 23(1), ‘appointment as teacher’ refers to appointment from external sources and not from internal sources.

h. TET is not mandatory but only directory as: (i) Notification dated 23rd August, 2010, limits TET to classes I–VIII, despite NCTE’s authority under Section 12A of the National Council for Teacher Education Act,199329 to set qualifications up to the intermediate level; (ii) clauses 3 and 4 of the same notification allow exceptions where the TET is not required for appointment or continuation as a teacher; and (iii) consequences of not qualifying the TET are not provided in the RTE Act.

i. Teachers appointed to classes I to VIII prior to the date of the notification dated 23rd August 2010 (vide which NCTE laid down minimum qualifications for appointment of teachers for classes I to V and classes VI to VIII) would not be required to pass the TET for their appointment to remain valid, for, the said notification does not provide for minimum qualifications for promotions.

j. The valid and invalid provisions of the RTE Act are inseparable and, thus, the entire RTE Act cannot apply to minorities and if, at all, the issue must be referred to a larger Bench, the same has to be restricted to the applicability of Section 23 of the RTE Act.

k. The Constitution Bench in Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra) upheld the exemption granted to minorities under Article 15(5), to protect the minority character of the institutions, and to prevent the majority from making a law permitting others to be imposed in a minority institution.

l. Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan (supra) held that minority educational institutions under Article 30(1) form a separate category of institutions.

m. In Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra), this Court, going a step further from what was held in Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan (supra) held that all minority institutions, whether aided or unaided, would not fall within the purview of the RTE Act.

n. In view of Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra), the RTE Act cannot apply to minority institutions, and would be in violation of Article Furthermore, if the RTE Act in its entirety does not apply, the question of applying sections 12 or 23 of the RTE Act, does not arise.

o. The subject matter in Society for Unaided Private Schools of Rajasthan (supra) was with respect to the validity of the RTE Act, whereas, Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra) considered the validity of both Article 15(5) and Article 21A.

p. Imposing TET qualification for promotion may cause stagnation, which could not have been the intention of the Parliament. Opportunity for promotion is vital in public service, for, promotion boosts proficiency, while stagnation hampers effectiveness (see CSIR KGS Bhatt30);

q. There cannot be retrospective removal of right of retrospectively revoking benefits acquired under existing rules would violate Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution (see T.R. Kapur vs. State of Haryana31).

56. Supporting the plea for a reference to reconsider Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra) and that the TET qualification is mandatory, arguments as follows were advanced:

a. The right of each and every child to be taught by qualified teachers is integral to Right to Education. This right cannot be limited or impeded, except to the limited extent provided for under Article 29 or Article 30 of the Constitution.

b. Laying down higher standards is the logic of enhancing knowledge acquisition and is an independent facet of the right to The management of minority educational institution has no right to interfere with the educational rights of the children.

c. To exempt a particular category of institutions would be contrary to Article 21A of the Constitution of India and create an artificial distinction. The State holds a positive obligation to ensure that every child, irrespective of caste, creed or religion, receives quality education on equal footing.

d. Article 30, granting the minorities a right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice, does not override the State’s duty to ensure that the quality of education imparted remains consistent across all institutions. Even if an educational institution is an aided minority institution, it does not provide a constitutionally valid exemption for applying a different eligibility criterion for the recruitment and promotion of teachers based on religion or language. While considering T.M.A. Pai Foundation (supra), Secy., Malankara Syrian Catholic College v. T. Jose32 held that the right of minorities to administer minority institutions under Article 30 is not to place the minorities in a better or more advantageous position. There cannot be reverse discrimination in favour of the minorities. The freedom to appoint teachers and lecturers would be subject to eligibility conditions/ qualifications.

e. A classification that seeks to differentiate the eligibility criteria for teachers based on the religious character of an institution would create an unreasonable distinction between children studying in minority-aided institutions and those in other institutions, violating Articles 14 and 21A.

f. The exemption from adhering to essential eligibility norms, i.e., the TET, would be an arbitrary classification, based neither on intelligible differentia nor bears any rational nexus with the objective sought to be achieved. This would violate Article 14 and deprive the students of the standard of education available in other institutions.

g. The burden on the State to select quality teachers lies entirely on the State. In such process, the State has an obligation and authority to regulate the quality of education, including education imparted in minority educational institutions. T.M.A. Pai Foundation (supra), as reiterated in Brahmo Samaj Education Society & Ors. v. State of West Bengal33, Sindhi Education Society v. Chief Secretary Govt. of Delhi34, Chandana Das (Malkar) v. State of West Bengal35, were cited.

h. The educational institutions may have the liberty to grant relaxation to meet exigent circumstances, however, such relaxations may not continue indefinitely; also, relaxations cannot be granted to distort the regulation of Reliance was placed on Committee of Management, Vasanta College for Women v. Tribhuwan Nath Tripathi36 and Food Corpn. of India v. Bhanu Lodh37.

i. TET is a mandatory and an indispensable qualification/eligibility criterion to ensure the maintenance of quality education, irrespective of their classification as minority/majority or aided/un-aided institutions. TET applies to recruitment and promotions, subject to statutory rules.

j. The NCTE Act was amended to insert Section 12A, which gave effect to Section 23 of the RTE Act, granting power to the Council to determine minimum standards of education of school teachers. The National Council for Teachers Education (Determination of Minimum Qualifications for Persons to be Recruited as Education Teachers and Physical Education Teachers in Pre-primary, Primary, Upper Primary, Secondary, Senior Secondary or Intermediate Schools or Colleges) Regulations, 201438 are to be read along with Section 12A of the NCTE Act which refers to notification relaxing qualification by notification dated 23rd August, 2010 to interpret that the TET and other minimum qualifications are mandated and could have been obtained by teachers within 9 years as specified under the RTE Act and the NCTE Rules/Regulations.

k. Articles 15(5), 15(6) and 21A must be treated as the trilogy of education rights. Merely because Articles 15(5) and 15(6) exclude minority institutions from its scope, it must not be construed that they are relieved from their social justice obligation to aid and assist the emancipation of weaker sections of the society. While the State may not interfere with the right of management of the minority institutions, it does not mean that they cannot be called upon to share the obligations of social justice under Articles 15 and 21A of the Constitution. Thus, the State may not insist upon minority institutions to abide by Section 23 of the RTE Act unconditionally, but it can subject them to other regulatory Minority institutions may be subject to absolutely minimal and negative controls. It will be a travesty of Constitutional scheme of attainment of excellence if such exclusions are provided.

l. A composite reading of Section 23(2) of the RTE Act along with the proviso thereto would reveal that the RTE Act provides 9 years for the teachers to acquire such minimum qualifications, as may be prescribed. Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Rules, 201039, framed under the RTE Act, must be read along with Section 23.

m. In exercise of powers under Section 35(1) of RTE Act, the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India40 has issued guidelines vide communication F No. 1-15/2010 EE4 dated 08th November, 2010 for implementation and relaxation of qualifications under Section 23(2) of the RTE Act, conveying that the condition of passing the TET cannot be relaxed by the Central Government.

n. The National Council for Teacher Education (Determination of Minimum Qualifications for Recruitment of Teachers in Schools) Regulations, 2001 were framed under the NCTE NCTE also issued a notification dated 23rd August, 2010 mandating TET for appointment of teachers for standards I to VIII. In furtherance of this notification, NCTE also issued guidelines dated 11th February, 2011 for conducting the TET.

o. MHRD vide O.No.17-2/2017-EE.17 dated 03rd August, 2017 issued to all States and Union Territories reiterated the last chance being given to acquire the requisite minimum qualifications and also warned that in-service teachers would not be allowed to continue beyond 01st April, 2019 without acquiring the requisite minimum qualifications.

p. In terms of Union of India v. Pushpa Rani41,as reiterated in Hardev Singh Union of India42, the employer (being the State) has the absolute right of fixing the qualifications for recruitment and promotion and that the court cannot sit in appeal over the discretion of the employer. The policy of employment and promotion is the exclusive domain of the employer, as per J. Ranga Swamy v. Govt. of Andhra Pradesh43. Also, there is no vested right to promotion is the law settled by Union of India v. Krishna Kumar44.

q. Judgment of a larger Bench of this Court can be explained by a smaller bench. Similarly, the judgment in Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra), in particular paragraph 55, can be adequately explained in the present case by providing a context to the RTE Act with the NCTE scheme. Only in the event that this exercise cannot be undertaken, the question of reference to a larger Bench may arise.

r. Paragraph 55 of Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra) is merely obiter dicta and will not lead to a conclusion insofar as applicability/eligibility criteria for appointment of teachers is concerned. Applicability of the RTE Act to minority institutions was incidental to the main issue and not essential to the decision.

s. In Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra), this Court was never called upon to decide the constitutional validity of the entire RTE Act or even Section 23 thereof. The Court was restricted to the validity of the Constitution (Ninety-third) Amendment Act, 2005 and Constitution (Eighty-sixth) Amendment Act, 2002. It cannot be said that the Constitution Bench in Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra) was seized of the question as to whether the entire RTE Act was unconstitutional.

t. Regulation of teachers’ qualification, such as the TET, fall within the permissible regulatory measure as the object is to maintain educational quality and standards. Application of paragraph 55 of Pramati Educational & Cultural Trust (supra) as a strait-jacket principle would lead to untenable position where students in minority institutions would be taught by teachers who do not meet the minimum qualification, thereby compromising educational quality. Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra) did not lay down any binding law to hold the entirety of the RTE Act as unconstitutional and its observations must be restricted to Section 12(1)(c).

u. As held in Zee Telefilms v Union of India45 , judgments of this Court should not be read like a statute or Euclid’s theorems; observations 99(2005) 4 SCC 649))made therein must be read in the context in which it A point which was not raised before the Court would not be an authority on the said question and that per B. Shama Rao v. Union Territory of Pondicherry46, a decision is binding not because of its conclusion but what is binding is its ratio and the principle laid down therein.

v. State of Orissa v. Sudhanshu Sekhar Misra47 and Director of Settlements, Andhra Pradesh M.R. Appa Rao48 were placed to emphasize the role of this Court in interpreting its judgments. Further, the dissenting opinion authored by Hon’ble A.P. Sen J., in Dalbir Singh v. State of Punjab49 was cited to emphasize on the phrase ‘law declared’ under Article 141, to limit its application in the facts and context of the matter in which the case was decided. On the principle of binding value of judgment wherein a conclusion of law was neither raised nor preceded by consideration, reference was made to the judgment in the case of State of UP v. Synthetics & Chemicals Ltd.50 Further, reliance was placed on Arnit Das v. State of Bihar51 that a judgment rendered sub-silentio cannot be deemed to be a law declared to have a binding effect as contemplated under Article 141. Also, on the principle of sub-silentio, Madhav Rao Jivaji Rao Scindia v. Union of India52 was cited.

w. Thus, this Court would be within its authority to explain the precedential value of a larger Bench judgment, only in cases where the ratio and the conclusions do not match. The authority that this Court possesses to explain a previous judgment will be treated as an integral part of its constitutionally acknowledged adjudicatory

x. The authority available to the State Government under Article 309 is a general power and must yield to the special statutory authority enacted under the NCTE Consequently, rules or executive orders issued by the State Government to keep the application of the NCTE Regulations out of reckoning will also be bad in law.

y. In Christian Medical College Vellore Assn. v. Union of India53, considering the issue of applicability of the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test, this Court held that minority institutions are equally bound to comply with the conditions imposed under the relevant Act and Regulations, which apply to all institutions. The National Education Policy (NEP), 2020 also makes the TET mandatory for all levels of teaching. The right to administer minority institutions does not grant the right to mal-administer an institution to the detriment of the students.

z. In case of transition between two realms or settings, relaxations may be When in such a scenario the State is found to be lacking in its policy, provisions of Article 142 may be invoked. In the present set of facts, Section 23 of the RTE Act read with Section 12A of the NCTE Act have been enacted by the Legislature towards reasonable transition process. If the teachers appointed prior to the cut-off date fail to adhere to the statute, their case may deserve a differential treatment but not to the extent of altering the core meaning of the statute.

II. The Acts, Rules, Regulations and Notifications

57. After introduction of the RTE Act, the NCTE Act came to be amended to make it in line with Article 21A of the Constitution as well as the RTE Act. The long title of the NCTE Act was also amended to include the regulation of qualifications of school teachers.

58. Further, Section 1 was amended to include sub-section (4), which made the NCTE Act applicable to schools’ imparting pre-primary, primary, upper-primary, secondary or senior secondary schools. Section 2 was amended to include the definition of school which, among other things, included schools not receiving any aid or grants to meet whole or part of its expenses from a government or local authority.

59. The amendment that assumes primacy for the present issue was the insertion of section 12A, the marginal note of which reads, ‘Power of Council to determine minimum standards of education of school teachers’. The aforesaid section permits the Council, i.e., the NCTE, to determine the qualifications of teachers in schools, by way of regulations. The further proviso to this section provides that the minimum qualifications of a teacher must be acquired within the period specified in the NCTE Act or the RTE Act.

60. Section 23 of the RTE Act authorizes the Central Government to authorize an academic authority to lay down “minimum qualifications” for being eligible to be appointed as a teacher:

“23. Qualifications for appointment and terms and conditions of service of teachers.—(1) Any person possessing such minimum qualifications, as laid down by an academic authority, authorised by the Central Government, by notification, shall be eligible for appointment as a teacher. …”

61. In exercise of such powers, the Central Government vide Notification S.O. 750(E) dated 31st March, 2010 appointed NCTE as the “academic authority” to lay down the minimum qualifications for a person to be eligible for appointment as a teacher.

62. Pursuant thereto, NCTE vide Notification No.61- 03/20/2010/NCTE/(N&S) dated 23rd August, 2010 laid down minimum qualifications for a person to be eligible for appointment as a teacher in classes I to VIII in a school referred to in clause (n) of Section 2 of the RTE Act54 This is when the TET was made mandatory for the first time.

Clause 355 of the notification provided for compulsory training for certain categories of teachers.

Clause 456 excluded certain categories of teachers from the requirement of attaining minimum qualifications specified in paragraph (1).

As per clause 557 , if any advertisement for appointment of teachers had already been issued prior to the date of the notification, such appointments were to be made in accordance with the NCTE Regulations, 2001.

63. By three subsequent notifications58, NCTE made amendments in the notification dated 23rd August, 2010. Inter alia, certain changes were made in clause 1 (which laid down minimum qualifications for appointment) regarding the educational requirement. Without going much into the details of the amendment, suffice it is to mention that the mandatory requirement of TET remained unchanged.

64. We consider it important to refer to certain parts of the notification dated 11th February, 2011 issued by NCTE vide which guidelines were issued for conducting the TET examination, highlighting the rationale for mandating the TET:

“3 The rationale for including the TET as a minimum qualification for a person to be eligible for appointment as a teacher is as under:

i. It would bring national standards and benchmark of teacher quality in the recruitment process;

ii. It would induce teacher education institutions and students from these institutions to further improve their performance standards;

iii.It would send a positive signal to all stakeholders that the Government lays special emphasis on teacher quality”

65. On 6th March, 2012, the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) issued a circular stating that all teachers hired after the date of circular, to teach classes I to VIII students in CBSE-affiliated schools must pass the Teacher Eligibility Test (TET).

66. On 12th November, 2014, the NCTE laid down regulations, inter alia, providing for qualifications for recruitment of teachers for imparting education from pre-primary level to the senior secondary level. It will suffice to mention that the minimum qualifications for teachers teaching primary and upper primary (classes I to VIII) were the same as provided in the notification dated 23rd August, 2010.

67. As discussed above, NCTE made the TET a mandatory requirement vide its notification dated 23rd August, 2010. Be that as it may, in the year 2017, the Parliament made an amendment59in Section 23 of RTE Act by introducing a proviso in section 23(2) of the The proviso reads thus:

“Provided further that every teacher appointed or in position as on the 31st March, 2015, who does not possess minimum qualifications as laid down under sub-section (1), shall acquire such minimum qualifications within a period of four years from the date of commencement of the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (Amendment) Act, 2017.”

68. The Parliament, therefore, provided an opportunity to teachers appointed/in service, prior to 31st March, 2015 and who had not attained the minimum qualifications as prescribed (including the TET) to acquire the said qualifications within a period of four years from the date of commencement of the Amendment Act which was 1st April, 2017.

69. On 3rd August, 2017, the Additional Secretary, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Department of School Education & Literacy, issued a letter to the State secretaries, reminding that the last date to acquire minimum qualifications is 1st April, 2019, and no teacher, who did not possess minimum qualifications under the RTE Act, would be permitted to continue in service beyond the given date.

VI. Analysis and Reasons

70. The task at our hand is indeed onerous. Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra), being a decision rendered by a Constitution Bench of this Court, deserves due deference. While the said decision does shed light on key issues and provides valuable insights, it also leaves some questions open that could be explored further and productively addressed.

71. The two issues we are tasked to decide, which are indeed very significant for the future generations of our nation, bring in its train one more important issue: whether the decision of the Constitution Bench of five Judges of this Hon’ble Court in Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra), insofar as it exempts minority schools—whether aided or unaided—falling under clause (1) of Article 30 of the Constitution from the applicability of the RTE Act, warrants reconsideration. In course of our analysis, we propose to consider whether Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra) should be accepted as the last word in the matter of applicability of the RTE Act to minority institutions or whether there is a need to explore its efficacy as a binding precedent in the changed circumstances.

A. From promise to right: the constitutional journey of Article 21A and the right to elementary education in India

72. The right to elementary education in India did not begin its journey as a fundamental In the Constitution, as originally drafted, elementary education was initially recognized only as a Directive Principle of State Policy60under Article 45, which provided:

“The State shall endeavour to provide, within a period of ten years from the commencement of this Constitution, for free and compulsory education for all children until they complete the age of fourteen years.”

73. Article 45 seems to be the only directive principle framed with a specific time frame, reflecting the urgency and significance that the framers of the Constitution placed on its implementation. This directive, though aspirational, was unfortunately not judicially enforceable and depended heavily on the discretion and capacity of the State. The framers of the Constitution consciously placed ‘EDUCATION’ in Part IV, recognizing its criticality but also acknowledging the financial and administrative limitations of the newly independent nation.

74. The drafting history of the Constitution reveals that the inclusion of elementary education as a fundamental right was deliberated upon but ultimately deferred. Several members of the Constituent Assembly advocated for a justiciable fundamental right to education, arguing that without education, other rights and civil liberties would remain meaningless61). However, a competing viewpoint—concerned with resource constraints and state capacity—prevailed62. This led to the compromise of placing the right to elementary education as a non- enforceable and a non-binding directive principle, to be pursued by the State progressively over time.

75. However, through judicial pronouncements, the movement to recognize education, particularly elementary education, as a fundamental right gained momentum.

76. A decade before the enactment of the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, which introduced Article 21A, a two-Judge Bench of this Court in Mohini Jain v. State oF Karnataka63 held:

“12. … The right to education flows directly from right to life. The right to life under Article 21 and the dignity of an individual cannot be assured unless it is accompanied by the right to education. The State Government is under an obligation to make endeavour to provide educational facilities at all levels to its citizens.

17. We hold that every citizen has a ‘right to education’ under the Constitution. The State is under an obligation to establish educational institutions to enable the citizens to enjoy the said right. The State may discharge its obligation through state-owned or state-recognised educational institutions. When the State Government grants recognition to the private educational institutions it creates an agency to fulfil its obligation under the Constitution. The students are given admission to the educational institutions — whether state-owned or state-recognised — in recognition of their ‘right to education’ under the Constitution. Charging capitation fee in consideration of admission to educational institutions, is a patent denial of a citizen’s right to education under the Constitution.”

77. However, in Unni Krishnan, J. P. v. State of Andhra Pradesh64, the correctness of the decision in Mohini Jain (supra) was challenged by private educational Though the decision was not affirmed in its entirety, the lead judgment of the five-Judge Constitution Bench of this Court further expanded the right to elementary education and while holding that a child up to the age of 14 years has a fundamental right to free education, held as follows:

“171. In the above state of law, it would not be correct to contend that Mohini Jain was wrong insofar as it declared that ‘the right to education flows directly from right to life’. But the question is what is the content of this right? How much and what level of education is necessary to make the life meaningful? Does it mean that every citizen of this country can call upon the State to provide him education of his choice? In other words, whether the citizens of this country can demand that the State provide adequate number of medical colleges, engineering colleges and other educational institutions to satisfy all their educational needs? Mohini Jain seems to say, yes. With respect, we cannot agree with such a broad proposition. The right to education which is implicit in the right to life and personal liberty guaranteed by Article 21 must be construed in the light of the directive principles in Part IV of the Constitution. So far as the right to education is concerned, there are several articles in Part IV which expressly speak of it. Article 41 says that the ‘State shall, within the limits of its economic capacity and development, make effective provision for securing the right to work, to education and to public assistance in cases of unemployment, old age, sickness and disablement, and in other cases of undeserved want’. Article 45 says that ‘the State shall endeavour to provide, within a period of ten years from the commencement of this Constitution, for free and compulsory education for all children until they complete the age of fourteen years’. Article 46 commands that ‘the State shall promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and, in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation’. Education means knowledge — and ‘knowledge itself is power’. As rightly observed by John Adams, ‘the preservation of means of knowledge among the lowest ranks is of more importance to the public than all the property of all the rich men in the country’. (Dissertation on Canon and Feudal Law, 1765) It is this concern which seems to underlie Article 46. It is the tyrants and bad rulers who are afraid of spread of education and knowledge among the deprived classes. Witness Hitler railing against universal education. He said: ‘Universal education is the most corroding and disintegrating poison that liberalism has ever invented for its own destruction.’ (Rauschning, The Voice of Destruction : Hitler speaks.) A true democracy is one where education is universal, where people understand what is good for them and the nation and know how to govern themselves. The three Articles 45, 46 and 41 are designed to achieve the said goal among others. It is in the light of these Articles that the content and parameters of the right to education have to be determined. Right to education, understood in the context of Articles 45 and 41, means : (a) every child/citizen of this country has a right to free education until he completes the age of fourteen years, and (b) after a child/citizen completes 14 years, his right to education is circumscribed by the limits of the economic capacity of the State and its development. […].

175. Be that as it may, we must say that at least now the State should honour the command of Article 45. It must be made a reality — at least now. Indeed, the National Education Policy 1986 says that the promise of Article 45 will be redeemed before the end of this century. Be that as it may, we hold that a child (citizen) has a fundamental right to free education up to the age of 14 years.”

(emphasis in original)

78. The decision in Unni Krishnan (supra), however, stands overruled by an eleven-Judge Constitution Bench of this Hon’ble Court in M.A. Pai Foundation (supra) albeit on a different point.

79. These two decisions together interpreted Article 21, e., the right to life, as including the right to elementary education, providing the groundwork for its constitutional recognition as a fundamental right. The right to life and dignity was held to be incomplete without access to basic education, thus, reading into the Constitution an implicit fundamental right to education even before it was formally codified in 2002.

80. These judicial efforts culminated in the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, which introduced Article 21A into the

81. Alongside Article 21A, the amendment also substituted Article 45 to focus on early childhood care and education and introduced a corresponding fundamental duty under Article 51A(k), requiring parents and guardians to ensure educational opportunities for their children between the ages of 6 and 14.

82. Article 21A, thus, marked a constitutional transformation by elevating the child’s right to free and compulsory elementary education to the status of an enforceable fundamental right.

83. Notably, the right to education which is positioned right after the right to life and personal liberty, underscores the intrinsic connection between life and knowledge acquisition, to be gained through elementary education. This sequence of rights is also reflective of Parliament’s consciousness of the critical nexus between knowledge and human dignity.

84. Indubitably, Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust (supra) could not have and, as such, did not see anything objectionable in Article 21A to hold that it trenches upon minority rights protected by Article 30. What it said is that the power under Article 21A vesting in the State does not extend to making a law to abrogate minority rights of establishing and administering schools of their choice.

B. Breathing life into the promise: the RTE Act and the realisation ofArticle 21A

85. To give effect to the newly inserted fundamental right, e., Article 21A, Parliament enacted the RTE Act. The RTE Act breathed life into Article 21A by providing a comprehensive statutory framework to ensure access to free, compulsory, and quality elementary education for all children in the 6–14 age group.

86. As outlined in the Statement of Objects and Reasons accompanying the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Bill, 200865, the objectives of the RTE Bill read:

“The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Bill, 2008, is anchored in the belief that the values of equality, social justice and democracy and the creation of a just and humane society can be achieved only through provision of inclusive elementary education to all. Provision of free and compulsory education of satisfactory quality to children from disadvantaged and weaker sections is, therefore, not merely the responsibility of schools run or supported by the appropriate Governments, but also of schools which are not dependent on Government funds.”

87. Viewed holistically, the RTE Act—contrary to the commonly held belief— does not impose an onerous or excessive regulatory burden; rather, it lays down the bare minimum core obligations and standards that all schools [as defined in Section 2(n)] must follow to ensure that the constitutional promise envisioned by Article 21A is not rendered meaningless. They include requirements such as trained teachers, student-teacher ratio, adequate infrastructure, inclusive admission policies, age-appropriate common curriculum, etc. All these are indispensable to deliver quality elementary education.

88. At its heart, the RTE Act is an instrument for universalisation of education, which is rooted in the values of social inclusion, national development, and child-centric growth. It is aimed at bridging the gap between privileged and disadvantaged, and it ensures that every child, regardless of caste, creed, class, or community, is given a fair and equal opportunity to learn, grow, and thrive. The RTE Act is designed not to stifle institutional autonomy but to uphold a threshold of dignity, safety, equity, and universality in the learning environment for a child.

89. Born of Article 21A, the RTE Act is not merely another addition to the statute books. It is the living expression of a long-deferred promise. When the Constitution was first adopted, the right to education could find place only among the Directive Principles, tempered by the economic and institutional limitations of a newly independent nation; yet, the vision was never abandoned but merely postponed. It took the nation over half a century of democratic maturity, social awakening, and judicial insistence for this vision to be shaped into a fundamental right.

90. In this sense, Article 21A stands, perhaps, a shade taller than many other rights, not merely by hierarchy but by the weight of the journey it carries—a journey of struggle, consensus, and above all, a reaffirmation that right to elementary education is not charity, but justice.

91. Against this backdrop, if a conflict were ever to arise between the two competing fundamental rights, i.e., Article 21A and Article 30, it must be remembered that not all rights stand on equal footing when their purposes diverge and reconciliation is no longer possible. In such a scenario, Article 30, though crucial in preserving cultural and educational autonomy, must be interpreted in tandem with Article 21A, for the latter is not merely a fundamental right but we consider it to be the foundation upon which the other rights of the younger generation would find meaning and voice. Article 21A is not just a right in isolation, it is an enabler of other fundamental rights, a unifying thread that weaves together the garland of all other fundamental rights promised by our Constitution. Despite transition from Part IV to Part III of the Constitution, much of the object and purpose for introduction of Article 21A would seem lost if means to provide free and compulsory education, which is sought to be achieved by enacting the RTE Act, were withheld for minorities for no better reason than that the RTE Act abrogates their right protected under Article 30. Education for children aged 6–14 is foundational for their development and the broader goals of nation building. The right to speak freely could ring hollow, the right to vote could become mechanical and the right to livelihood could largely be rendered meaningless when the younger generation were to grow up and transition to To deny Article 21A its rightful primacy is to reduce it to a skeletal promise—a right without fundamentals, stripped of the very essence that animates our constitutional vision.

92. Any interpretation that diminishes the scope or limits the application of the RTE Act must, therefore, be critically examined against the broader backdrop of the constitutional evolution as traced aforesaid.

C. The constitutional goal of universal elementary education and common schooling system

93. It is only in furtherance of its commitment to universal elementary education that Parliament enacted the Constitution (Eighty-sixth Amendment) Act, 2002, introducing Article 21A and elevating the right to free and compulsory education for all children aged between 6 and 14 years to the status of a fundamental right.

94. Therefore, at the outset, we must and do recognise that under the RTE Act, our focus is on elementary education which is the foundational building block of a child’s journey of learning, rather than tertiary or higher education. Since independence, Universal Elementary Education and the idea of a common schooling system have stood among the foremost national as well as constitutional We may ask, why does the universalisation of elementary education matter so deeply? The answer is not far to seek. It is at this stage that the seeds of equality, opportunity, and national integration are sown—shaping not only individual futures but the very character of the nation.