Age-Restriction on Couples Intending to Parent Through Surrogacy

Vijaya Kumari v Union of India

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that couples who had commenced the surrogacy process cannot be denied their right to parenthood only because of the age bar under the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021.

Three couples intending to become parents had commenced the surrogacy process, prior to the commencement of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act,...

Case Details

Judgement Date: 9 October 2025

Citations: 2025 INSC 1209 | 2025 SCO.LR 10(2)[9]

Bench: B.V. Nagarathna J, K.V. Viswanathan J

Keyphrases: Section 4(iii)(c)(I) of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021—date of commencement—upper age limit—50 for female—55 for male—No retrospective application of the Act—if intending couples had begun surrogacy process before commencement of the Act—Right to have child through surrogacy—constitutional right regulated by statute—Other couples similarly placed and aggrieved with age-restriction may approach jurisdictional High Court.

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

NAGARATHNA, J

These two writ petitions and one interlocutory application arise out of a set of similar but slightly differentiated facts. The common legal question arising out of them is the application of the age-restrictions on ‘intending couples’ under Section 4(iii)(c)(I) of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 (hereinafter referred to as “the Act” for the sake of brevity).

2. The Act came into force with effect from 25.01.2022. The objects of the Act are the regulation of the practice and process of surrogacy and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. The relevant definitions of the Act read as under:

“2. Definitions. — (1) In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,—

xxx

(b) “altruistic surrogacy” means the surrogacy in which no charges, expenses, fees, remuneration or monetary incentive of whatever nature, except the medical expenses and such other prescribed expenses incurred on surrogate mother and the insurance coverage for the surrogate mother, are given to the surrogate mother or her dependents or her representative;

(c) “appropriate authority” means the appropriate authority appointed under Section 35;

xxx

(g) “commercial surrogacy” means commercialisation of surrogacy services or procedures or its component services or component procedures including selling or buying of human embryo or trading in the sale or purchase of human embryo or gametes or selling or buying or trading the services of surrogate motherhood by way of giving payment, reward, benefit, fees, remuneration or monetary incentive in cash or kind, to the surrogate mother or her dependents or her representative, except the medical expenses and such other prescribed expenses incurred on the surrogate mother and the insurance coverage for the surrogate mother;

(h) “couple” means the legally married Indian man and woman above the age of 21 years and 18 years respectively;

(i) “egg” includes the female gamete;

(j) “embryo” means a developing or developed organism after fertilisation till the end of fifty-six days;

xxx

(l) “fertilisation” means the penetration of the ovum by the spermatozoan and fusion of genetic materials resulting in the development of a zygote;

(m) “foetus” means a human organism during the period of its development beginning on the fifty-seventh day following fertilisation or creation (excluding any time in which its development has been suspended) and ending at the birth;

(n) “gamete” means sperm and oocyte;

xxx

(r) “intending couple” means a couple who have a medical indication necessitating gestational surrogacy and who intend to become parents through surrogacy;

xxx

(v) “oocyte” means naturally ovulating oocyte in the female genetic tract;

xxx

(zd) “surrogacy” means a practice whereby one woman bears and gives birth to a child for an intending couple with the intention of handing over such child to the intending couple after the birth

xxx

(zf) “surrogacy procedures” means all gynaecological, obstetrical or medical procedures, techniques, tests, practices or services involving handling of human gametes and human embryo in surrogacy;

(zg) “surrogate mother” means a woman who agrees to bear a child (who is genetically related to the intending couple or intending woman) through surrogacy from the implantation of embryo in her womb and fulfils the conditions as provided in sub-clause (b) of clause (iii) of Section 4;

(zh) “zygote” means the fertilised oocyte prior to the first cell division.

(2) Words and expressions used herein and not defined in this Act but defined in the Assisted Reproductive Technology Act shall have the meanings respectively assigned to them in that Act.

2.1 Section 3 speaks of prohibition and regulation of surrogacy clinics, while Section 4 deals with regulation of surrogacy and surrogacy procedures. The expressions “surrogacy” and “surrogacy procedures” are defined in clauses (zd) and (zf) respectively of subsection (1) of Section 2 of the Act. Sections 4 and 53 read as under:

“4. Regulation of surrogacy and surrogacy procedures.— On and from the date of commencement of this Act, —

(i) no place including a surrogacy clinic shall be used or cause to be used by any person for conducting surrogacy or surrogacy procedures, except for the purposes specified in clause

(ii) and after satisfying all the conditions specified in clause (iii); (ii) no surrogacy or surrogacy procedures shall be conducted, undertaken, performed or availed of, except for the following purposes, namely:

(a) when an intending couple has a medical indication necessitating gestational surrogacy:

Provided that a couple of Indian origin or an intending woman who intends to avail surrogacy, shall obtain a certificate of recommendation from the Board on an application made by the said persons in such form and manner as may be prescribed.

Explanation.—For the purposes of this subclause and item (I) of sub-clause (a) of clause (iii) the expression “gestational surrogacy” means a practice whereby a surrogate mother carries a child for the intending couple through implantation of embryo in her womb and the child is not genetically related to the surrogate mother;

(b) when it is only for altruistic surrogacy purposes;

(c) when it is not for commercial purposes or for commercialisation of surrogacy or surrogacy procedures;

(d) when it is not for producing children for sale, prostitution or any other form of exploitation; and

(e) any other condition or disease as may be specified by regulations made by the Board;

(iii) no surrogacy or surrogacy procedures shall be conducted, undertaken, performed or initiated, unless the Director or in-charge of the surrogacy clinic and the person qualified to do so are satisfied, for reasons to be recorded in writing, that the following conditions have been fulfilled, namely:—

(a) the intending couple is in possession of a certificate of essentiality issued by the appropriate authority, after satisfying itself, for the reasons to be recorded in writing, about the fulfilment of the following conditions, namely: —

(I) a certificate of a medical indication in favour of either or both members of the intending couple or intending woman necessitating gestational surrogacy from a District Medical Board.

Explanation.—For the purposes of this item, the expression “District Medical Board” means a medical board under the Chairpersonship of Chief Medical Officer or Chief Civil Surgeon or Joint Director of Health Services of the district and comprising of at least two other specialists, namely, the chief gynaecologist or obstetrician and chief paediatrician of the district;

(II) an order concerning the parentage and custody of the child to be born through surrogacy, has been passed by a court of the Magistrate of the first class or above on an application made by the intending couple or the intending woman and the surrogate mother, which shall be the birth affidavit after the surrogate child is born; and

(III) an insurance coverage of such amount and in such manner as may be prescribed in favour of the surrogate mother for a period of thirtysix months covering postpartum delivery complications from an insurance company or an agent recognised by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority established under the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority Act, 1999 (41 of 1999);

(b) the surrogate mother is in possession of an eligibility certificate issued by the appropriate authority on fulfilment of the following conditions, namely: —

(I) no woman, other than an ever married woman having a child of her own and between the age of 25 to 35 years on the day of implantation, shall be a surrogate mother or help in surrogacy by donating her egg or oocyte or otherwise;

(II) a willing woman shall act as a surrogate mother and be permitted to undergo surrogacy procedures as per the provisions of this Act:

Provided that the intending couple or the intending woman shall approach the appropriate authority with a willing woman who agrees to act as a surrogate mother;

(III) no woman shall act as a surrogate mother by providing her own gametes;

(IV) no woman shall act as a surrogate mother more than once in her lifetime: Provided that the number of attempts for surrogacy procedures on the surrogate mother shall be such as may be prescribed; and

(V) a certificate of medical and psychological fitness for surrogacy and surrogacy procedures from a registered medical practitioner;

(c) an eligibility certificate for intending couple is issued separately by the appropriate authority on fulfilment of the following conditions, namely:–

(I) the intending couple are married and between the age of 23 to 50 years in case of female and between 26 to 55 years in case of male on the day of certification;

(II) the intending couple have not had any surviving child biologically or through adoption or through surrogacy earlier: Provided that nothing contained in this item shall affect the intending couple who have a child and who is mentally or physically challenged or suffers from life threatening disorder or fatal illness with no permanent cure and approved by the appropriate authority with due medical certificate from a District Medical Board; and

(III) such other conditions as may be specified by the regulations.

xxx

53. Transitional provision.— Subject to the provisions of this Act, there shall be provided a gestation period of ten months from the date of coming into force of this Act to existing surrogate mothers’ to protect their well being.

3. Presently, we are concerned with Section 4(iii)(c)(I). The same states that on and from the date of commencement of the Act, i.e., 25.01.2022, an intending couple requires an ‘eligibility certificate’ issued by the appropriate authority certifying that the intending couple are married and between the age of 23 to 50 years in case of the female and between 26 to 55 years in case of the male on the day of certification. The appropriate authority under Section 36 of the Act has to consider and grant or reject any application under clause (vi) of Section 3 and sub-clauses (a) to (c) of clause (iii) of Section 4 within a period of ninety days which also includes the power to issue eligibility certificate.

3.1 The common grievance of the petitioners and applicants herein is with regard to the upper age limit fixed for the intending couple, inasmuch as the female cannot be over and above 50 years of age and the male cannot be over and above 55 years of age.

4. In Writ Petition (Civil) No.331 of 2024, petitioner No.1 is the wife, and petitioner No.2 is the husband (hereinafter referred to collectively as ‘intending couple No.1’). In 2019, they were married under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. This was the second marriage for both the petitioners. Petitioner No.1 has one daughter from her previous marriage, and petitioner No.2 has two daughters from his previous marriage. All three children have attained adulthood and are living abroad.

4.1 The petitioners do not have children (biological, adopted or surrogate) together. Consequently, in 2020, they began IVF treatment to conceive a child. However, the couple was advised to opt for conceiving a child through surrogacy due to petitioner No.1’s advanced age, excessive bleeding during previous pregnancies and other issues.

4.2 On 28.08.2020, the first attempt at ‘egg retrieval’ (the process by which eggs are collected from a woman’s ovaries) from petitioner No.1 failed due to her age. On 30.10.2020, she was diagnosed with ovarian cysts. The petitioners subsequently approached Iswarya Fertility Centre, Chennai, where two eggs were successfully retrieved on 26.01.2021 and the embryos were frozen in preparation for transfer into a surrogate womb.

4.3 However, the petitioners contend that the process of transferring the embryo into the surrogate womb was stalled due to unforeseeable circumstances beyond their control, i.e., the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thereafter, on 25.01.2022, the Act came into effect and on 21.06.2022, the Surrogacy (Regulation) Rules, 2022 (for short, “Rules”) were promulgated.

4.4 On 03.02.2024, the petitioners took a second opinion from Iswarya Fertility Centre, Chennai, whose report opined that the couple needs surrogacy, in view of the risks during delivery and pregnancy experienced by petitioner No.1 in the past. However, it also noted that “the law does not permit surrogacy in view of age”.

Therefore, aggrieved, intending couple No.1 has preferred this writ petition, challenging the propriety of the age-restrictions under the Act, and also contending that they had commenced surrogacy procedures before the enforcement of the Act.

5. In Writ Petition (Civil) No.809 of 2024, petitioner No.1 is the wife, and petitioner No.2 is the husband (hereinafter referred to collectively as ‘intending couple No.2’). They were married on 07.02.2011 and registered their marriage under the Special Marriage Act, 1954. Intending couple No.2 submitted that they have been unable to conceive a child naturally with multiple unsuccessful attempts at frozen embryo transfer between the years 2012 and 2018. Intending couple No.2 submitted that in the year 2019, two embryos were made at the Southern Cross Fertility Centre, Mumbai, but the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 prevented the continuation of the process of surrogacy.

5.1 In 2022, the Act and the Rules were enforced, following which, the petitioners became ineligible for surrogacy procedures. This is because at the time of enforcement of the Act and Rules petitioner No.2 had crossed the age limit of 55 years prescribed for males under the Act. As on the date that the Writ Petition was filed, i.e., 21.10.2024, petitioner No.2 was 58 years old. Therefore, the intending couple No.2 has preferred this writ petition, contending that they have demonstrated a bona fide intent to avail the option of surrogacy through multiple aborted and failed attempts over the years. Further, they submitted that if they had anticipated the stringent age-related criteria under the Act, they would have availed the surrogacy option well in time.

6. The applicants in I.A. No.181569 of 2022 are hereinafter collectively referred to as ‘intending couple No.3’. As on date of the application, i.e., 23.11.2022, the applicant-husband was about 62 years old and the applicant-wife was about 56 years old. Intending couple No.3 lost their only child in 2018. Although they desired to conceive a child naturally again, they were advised to opt for InVitro Fertilisation (IVF) due to their advanced age.

6.1 In May 2019, the applicant-wife underwent an examination, and was deemed fit to bear an embryo with donor oocytes. However, due to the presence of fibroids in her uterus, it was advised that IVF be pursued with donor eggs. The applicant-wife then underwent Myomectomy Laparoscopic Surgery on 22.11.2019 and was nonetheless deemed fit to bear an embryo.

6.2 Intending couple No.3 submitted that the process was subsequently put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic, during which the applicant wife developed hypertension, due to which, the couple received medical advice that surrogacy was the advisable course of action. Having decided to transfer the embryo to the surrogate by April 2021, the applicants submitted that this process was further delayed by the second wave of the pandemic. Subsequently, although an embryo was successfully transferred to a surrogate mother in January 2022, the surrogate mother suffered a miscarriage and the pregnancy was not successful.

6.3 Thereafter, the Act and the Rules were enforced and intending couple No.3 has been rendered ineligible for undergoing surrogacy procedures since both applicant-wife and husband are above the age-limit of 50 years and 55 years respectively. Therefore, intending couple No.3 has preferred this application in W.P. (C) No.756/2022, contending that they had already begun the process of conducting medical procedures for the transfer of embryos to an identified surrogate mother. When they began such procedures, they were well within the ambit of the then prevailing law. It is only subsequently that they have been barred by the Act. Intending couple No.3 submitted that as on date, the embryos are ready to be transferred to the surrogate mother.

Submissions:

7. We have heard learned senior counsel Ms. Pinky Anand and Ms. Mohini Priya learned counsel for intending couple Nos.1, 2 and 3, and learned Additional Solicitor General (ASG) Ms. Aishwarya Bhati for the respondent-Union of India and perused the material on record.

7.1 Learned senior counsel for intending couple No.1 submitted as follows:

7.1.1 The provisions of the Act cannot be applied retrospectively to intending couples who had started surrogacy procedures much prior to its enforcement. In support of this contention, the judgement of a five-judge bench of this Court in CIT vs. Vatika Township (P) Ltd., (2015) 1 SCC 1 was relied on, the relevant portion of which is produced below:

“28. Of the various rules guiding how a legislation has to be interpreted, one established rule is that unless a contrary intention appears, a legislation is presumed not to be intended to have a retrospective operation. The idea behind the rule is that a current law should govern current activities. Law passed today cannot apply to the events of the past.”

7.1.2 In this case, the intending couple began their surrogacy procedures in January 2021 by freezing their embryos. When this process of freezing was begun, it was completely within the ambit of the then-prevailing law, which prescribed no upper age limit for either a man or woman to avail of surrogacy.

7.1.3 On a broader level, it was submitted that the fixation of an upper age-limit lacks rationale or justifiable basis, since the physical, emotional and financial capability to raise a child are not merely a function of age alone. Further, the imposition of an age cap on intending couples has no nexus with the core concerns of the Act, namely protecting surrogate mothers from exploitation and helping infertile parents bear children.

7.1.4 From a constitutional perspective, it was submitted that the upper age-limit falls foul of the right to reproductive autonomy under Article 21 of the Constitution. This right enables a woman to make autonomous decisions regarding, if, when, and in what manner to have children. Our attention was drawn to the following extract from the decision of this Court in X2 vs. State (NCT of Delhi), (2023) 9 SCC 433 (“X2 vs. State”):

“101. The ambit of reproductive rights is not restricted to the right of women to have or not have children. It also includes the constellation of freedoms and entitlements that enable a woman to decide freely on all matters relating to her sexual and reproductive health. Reproductive rights include the right to access education and information about contraception and sexual health, the right to decide whether and what type of contraceptives to use, the right to choose whether and when to have children, the right to choose the number of children, the right to access safe and legal abortions, and the right to reproductive healthcare. Women must also have the autonomy to make decisions concerning these rights, free from coercion or violence.”

7.1.5 In light of this decision, it was submitted that the agerestrictions under the Act run contrary to the constitutional right afforded to women to make unhindered decisions regarding their reproductive choices.

7.1.6 Further, it was submitted that the principle of ‘transformative constitutionalism’ supports the view that laws regulating new methods of family planning and childbearing, such as the Act, must align and support such societal shifts and therefore must not impose undue legal or regulatory burdens.

7.1.7 Learned counsel also submitted examples of international conventions and treaties to which India is a signatory that enshrine the right to parenthood. The Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), 1979 (ratified by India in the year 1993) recognises a woman’s right to freely make decisions on having children and access reproductive health services. The International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action, adopted in 1994 with India as a signatory, recognises reproductive rights and the importance of reproductive health services.

7.1.8 Therefore, intending couple No.1 have prayed that the fixation of an upper-age limit for intending couples availing surrogacy be struck down/read down. Further, they submitted that they were subject to exceptional and unforeseeable circumstances and hence pray that directions be issued to the National Board to allow them to proceed with surrogacy using their embryos frozen in the year 2021, i.e., prior to the coming into force the Act.

7.1.9 The right to access surrogacy procedures being a right that vested with couples that began procedures prior to the enforcement of the Act, cannot be taken away by a subsequent law, is a contention that was also advanced by learned senior counsel for intending couple No.1. In this regard, our attention was drawn to a judgement of this Court in S.L. Srinivasa Jute Twine Mills (P) Ltd. vs. Union of India, (2006) 2 SCC 740 (“S.L. Srinivasa Jute Twine Mills”).

7.1.10 Therefore, it was submitted that the language of Act does not specifically manifest its intention to apply the age-related restrictions retrospectively to intending couples who had begun the procedure for surrogacy prior to the enforcement of the Act. Hence, it cannot affect the vested right afforded to the petitioners to continue the surrogacy process that they had lawfully begun under the pre-existing legal regime.

7.1.11 Similarly, learned senior counsel for intending couple No.1 also drew our attention to the view of this Court in K. Gopinathan Nair vs. State of Kerala, (1997) 10 SCC 1 (“Gopinathan Nair”), wherein the majority observed that “it is now well settled that where a statutory provision which is not expressly made retrospective by the legislature seeks to affect vested rights and corresponding obligations of parties, such provision cannot be said to have any retrospective effect by necessary implication.”

7.2 Learned counsel for intending couple No.2 submitted as follows: The Act is a welfare legislation enacted to benefit couples bereft of the ability to conceive children naturally. However, the age-limits in Section 4(iii)(c)(I) bar couples who have unknowingly and due to bona fide reasons, crossed the thresholds. Petitioner No.1 (the wife) suffered repeated spontaneous abortions which demonstrates the bona fide reason and necessity to pursue surrogacy treatment. Therefore, the Act has taken away the vested’ right of the petitioners by imposing an age limit on availing the option of surrogacy.

7.2.1 Both intending couple Nos.1 and 2 drew our attention to an order of the Delhi High Court dated 10.10.2023 in Mrs. D & Anr. vs. Union of India & Anr., W.P.(C) No.12395/2023, wherein it granted interim protection to a couple that had similarly been denied surrogacy treatment due to the age-limits, despite having frozen embryos prior to the enforcement of the Act.

7.2.2 Learned counsel for intending couple No.2 further submitted that had the petitioners known about or anticipated the enforcement of such a law with stringent criteria, they would have specifically made sure to pursue surrogacy procedures (beyond the freezing of embryos) before petitioner No.2 (the husband) crossed the age limit. Therefore, ‘transitional provision’ that accommodated couples who had already commenced the surrogacy procedures in some form, is limiting irrational and arbitrary.

7.2.3 In this regard, our attention was drawn to a judgement of the Kerala High Court in Nandini K. vs. Union of India, 2022 SCC OnLine Ker 8235 in the context of similar age-restrictions under the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021 (‘ART Act’). It was observed that while the prescription of an upper age limit was not so “excessive and arbitrary” as to warrant judicial interference, the absence of a transitional provision was irrational and arbitrary.

7.2.4 Therefore, intending couple No.2 have prayed that Section 4(iii)(c)(I) of the Act be declared unconstitutional and that the petitioners may be permitted to continue surrogacy treatment despite the age of the petitioner-husband.

7.3 Learned counsel for intending couple No.3 submitted that the applicants, aged 62 (husband) and 56 (wife) respectively stand excluded from the process. Further, the applicant-wife is also excluded from the definition of ‘intending woman’ under the Act, as well as a ‘woman’ under the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021, leaving the couple incapable of pursuing Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) methods.

7.3.1 Learned counsel further submitted that the applicants had already selected an appropriate surrogate mother and were in the process of conducting the medical procedures required to transfer the embryos (which were ready) to the surrogate mother. Their disentitlement and ineligibility under the Act happened after they had already take substantial steps prior thereto. On the date that they began medical procedures, they were well within the ambit of the then prevailing law. As a matter of urgency, learned counsel submitted that the last semen analysis of the applicant husband was conducted at age 58. He is now already 62 and the chances of medical abnormalities and associated issues may rise.

7.3.2 Therefore, intending couple No.3 have prayed for directions to permit them to proceed with the medical procedures associated with carrying out a successful surrogacy.

8. Per contra, learned ASG for respondent-Union of India submitted that the object of the Act is to protect the individuals who are the most vulnerable (and consequently, whom the State has a higher degree of responsibility to protect) in the process, namely the surrogate mother and the child born through surrogacy. Specifically, the child has a right to adequate guardianship, which might otherwise have an impact on its quality of life.

8.1 Since surrogacy procedures involve the use of the body of a third individual, i.e., the surrogate mother, it was submitted that surrogacy can never be seen as the preferred option to conceive a child and should only be used as a last-resort measure. This is in contrast to the relatively less-restrictive regime under the ART Act, since ART procedures are conducted on one’s own body.

8.2 Further, since the Constitution does not recognise a right over another individual’s body, the right to avail surrogacy cannot be claimed as a fundamental right and exists purely as a statutory right subject to the conditions/restrictions prescribed in the Act. The right to reproductive autonomy is personal in nature (since Article 21 recognises the right to ‘personal liberty’) and does not subsume an individual’s right to use another’s body

8.3 Learned ASG submitted, that prior to the Act, courts were forced to adjudicate legal issues such as the right to parenthood through surrogacy in a legislative vacuum. Therefore, there was a need to ensure that the rights and interests of surrogate mothers and children are adequately protected.

8.4 It was submitted that the present trend in India is that the average age at which couples are getting married is higher than before. Therefore, the impugned upper age-limits on intending couples are also in alignment with this trend. The average age of menopause in India is 46.2 years and women older than 50 years of age have a higher likelihood of conceiving children with chromosomal conditions. Further, the sperm quality in men is compromised above the age of 55. Therefore, after consultation with stakeholders and domain experts, in the interests of surrogate children, a need was felt to place an upper-age limit on intending couples in order to ensure that the child born through surrogacy has a higher chance of a healthy life and access to adequate guardianship. It was also submitted that the child has a right to be raised by two parents of a reasonable age until the child attains majority and that this right supersedes any right claimed by the intending couple to bear a child through surrogacy. This is especially so when they have crossed the age-limits in question and may be classified incapable of providing adequate guardianship to the child.

8.5 Learned ASG also submitted that attempting to seek children beyond the prescribed age is ‘against the natural state of being’, since even natural birth is not unrestricted by age. By age 45, the fertility of a woman generally declines to such an extent that a natural pregnancy is unlikely.

8.6 In response to arguments challenging the constitutionality of the age-restrictions, it was submitted that the right to avail surrogacy is now only a statutory right and not a fundamental right. Further, the age-restrictions are based on a rational principle founded on scientific reasoning, introduced on the advice of domain experts. Therefore, it cannot be contended that the age-limits are arbitrary

8.7 It was further contended that while the classification created by the age-limits can be tested under Article 14, the fixation of the age-limits itself is a matter of legislative prerogative. In this regard, reliance was placed on the decision of this Court in Javed vs. State of Haryana, (2003) 8 SCC 369, wherein this Court upheld a legislation that disqualified persons having more than two living children from holding certain Panchayat offices as an exercise of legislative prerogative and wisdom which was not open to judicial scrutiny.

8.8 On the issue of non-retrospective application, learned ASG submitted that the Act does not recognise the ‘cryopreservation’ of gametes/embryos as a point of commencement of surrogacy procedure. Further, Parliament has indeed applied its mind to existing rights of individuals in the surrogacy process by making a ‘transitional provision’ in Section 53 of the Act. Therefore, it was submitted that the transitional period of ten months was only provided in favour of “existing surrogate mothers” and cannot be read to include any other category of people and this is the clear intention of the Parliament.

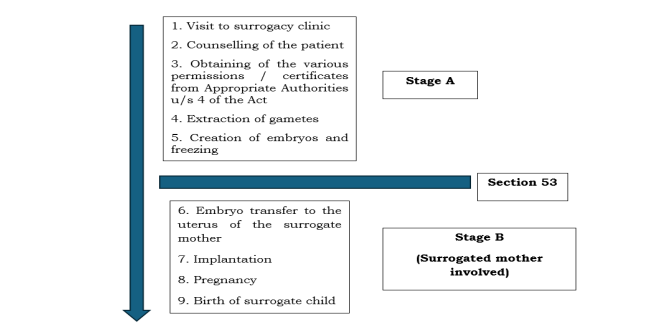

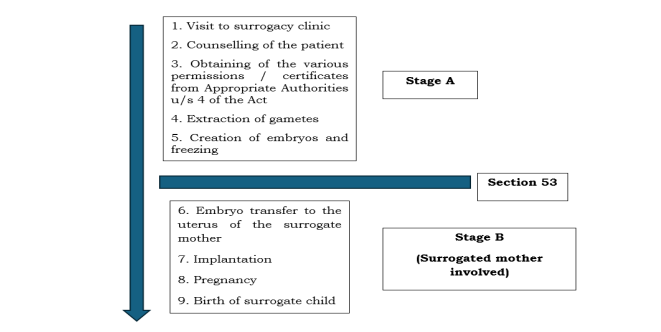

8.9 Learned ASG drew our attention to paragraph 97 of her written submissions, which shows that the process of surrogacy consists of two stages: Stage A and Stage B. The same is extracted as under:

“97. The process of surrogacy broadly entails the following stages:

8.10 Learned ASG submitted that the transitional period of ten months under Section 53 protects only Stage B of the surrogacy process, which involves the surrogate mother. The attempt of the petitioners is to move the line upwards, to cover individuals (intending couple) at various points in Stage A, which is against the intention of the Parliament.

8.11 It was further submitted that even if cryopreservation was done prior to the Act, it does not mean that surrogacy can then proceed de hors the provisions of the Act. Since surrogacy is now a statutory right, there can be no right to avail surrogacy in a manner beyond the scope of the Act.

8.12 It was also submitted that the Act was introduced after a long deliberative process over years, in which the draft Bill was made public. Two Parliamentary Committees also undertook public consultations. Therefore, individuals affected by the Act, including the petitioners and applicants herein, had the opportunity to understand and react to the impact of the Act on them at the relevant point in time. But today, they cannot plead that their rights, as they prevailed prior to the enforcement of the Act, be protected.

Issue for Consideration:

9. The issue that has arisen in these cases is that the appropriate authority would not have the power to issue an eligibility certificate to undertake a surrogacy procedure under Section 4 of the Act to an intending couple if the female is above 50 years of age and the male is above 55 years of age on the date of certification. The common contention of learned senior counsel and learned counsel for the petitioners as well as applicant is that they had commenced the surrogacy procedures prior to the date of enforcement of the Act, i.e., prior to 25.01.2022 and therefore, when they were in the midst of such a procedure, the Act brought in an embargo in the form of the aforementioned age-limit. As a result, they are barred from continuing the surrogacy procedure post the enforcement of the Act, although the same had been commenced much prior to the Act.

9.1 In this regard, our attention was drawn to the transitional provision which only protects the surrogate mother undergoing a surrogacy procedure for a period of ten months but not an intending couple undertaking such a procedure. Therefore, there is a challenge to the fixation of the maximum age under the Act. It was contended that all intending couples who had commenced surrogacy procedures prior to the enforcement of the Act may be permitted to continue with the same. It was submitted that the age of the intending couple would have no bearing on the procedure of surrogacy. That, if there is no bar on bearing a child at that age by a natural process, or for adopting an infant under the personal law, then such an embargo regarding age should not be applied in the case of an intending couple having a child by a surrogacy procedure. That couples resort to surrogacy as a last resort and if by the time of seeking certification under Section 4 of the Act, they have crossed the age bar, they would be deprived of parenthood. It was submitted that in the case of these petitioners and applicants, the surrogacy procedure had commenced long before the coming into force of the Act and the parties had also frozen the embryos and were at a crucial stage of the process when the age-bar under the Act led to a frustration of the procedure itself. Therefore, it was contended that where intending couples had commenced surrogacy procedures prior to the enforcement of the Act, they may be permitted to complete the same, irrespective of their age on the date of certification, if they otherwise comply with the requirements under the Act.

9.2 Per contra, learned counsel for the respondent-Union of India contended that with effect from the enforcement of the Act, no male or female or intending couple who have crossed the age bar can avail any surrogacy procedure leading to the birth of a child through surrogacy. Hence, she urged that the age limit on the date of certification, that determines eligibility for the purpose of availing surrogacy, must be read accordingly.

10. Section 4(ii)(a) of the Act mandates that no surrogacy procedures shall be conducted unless the intending couple “has a medical indication necessitating gestational surrogacy”. Further, Section 4(iii)(a)(I) provides that a ‘certificate of essentiality’ (issued by a District Medical Board) certifying a medical indication in favour of either or both members of the intending couple, is a pre-requisite for undertaking surrogacy procedures. The phrase “medical indication necessitating gestational surrogacy” is in turn defined under Rule 14 of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Rules, 2022, (‘Rules’, for short) which is reproduced below:

“14. Medical indications necessitating gestational surrogacy.—A woman may opt for surrogacy if;—

(a) she has no uterus or missing uterus or abnormal uterus (like hypoplastic uterus or intrauterine adhesions or thin endometrium or small unicornuate uterus, Tshaped uterus) or if the uterus is surgically removed due to any medical conditions such as gynaecological cancer;

(b) intended parent or woman who has repeatedly failed to conceive after multiple In vitro fertilization or Intracytoplasmic sperm injection attempts. (Recurrent implantation failure);

(c) multiple pregnancy losses resulting from an unexplained medical reason. unexplained graft rejection due to exaggerated immune response;

(d) any illness that makes it impossible for woman to carry a pregnancy to viability or pregnancy that is life threatening.”

10.1 In the cases of intending couple Nos.1, 2 and 3, it is not denied or contested that they qualify for surrogacy procedures based on the above reasons. Intending couple No.1 submitted that the petitioner-wife has suffered from excessive bleeding during prior pregnancies; intending couple No.2 submitted that they have suffered multiple failed attempts at embryo transfer between 2012 and 2018; and intending couple No.3 submitted that the applicantwife was unable to carry a child naturally due to fibroids in her uterus, and was advised to opt for surrogacy due to hypertension. The respondent-Union of India has not contested the fact that prima facie, all three intending couples may qualify as necessitating gestational surrogacy under the above Rule. However, this is subject to medical opinion in light of Rule 14 of the Rules.

10.2 Therefore, the question that falls for our adjudication is whether the age-restrictions under Section 4(iii)(c)(I) should be applied to intending couple Nos.1 to 3, all of whom had commenced the surrogacy process, to the extent of having their embryos frozen, before the enforcement of the Act. Concept of Surrogacy:

11. The first attempt at surrogacy regulation in India was in the form of the “National Guidelines for Accreditation, Supervision and Regulation of ART Clinics in India”, drafted by the Indian Council of Medical Research (‘ICMR’), and approved by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India in the year 2005. It defined ‘surrogacy’ as an “arrangement in which a woman agrees to carry a pregnancy that is genetically unrelated to her and her husband, with the intention to carry it to term and hand over the child to the genetic parents for whom she is acting as a surrogate”. It also prescribed a list of ‘general considerations’ for surrogacy procedures, for instance, HIV tests for prospective surrogate mothers, mandatory adoption of the child by the genetic parents and limits on how many times a woman can act as a surrogate. Importantly however, the aforesaid Guidelines did not forbid the practice of ‘commercial surrogacy’. This was also the case in the subsequent Draft ART Bill, 2008, which allowed the surrogate mother to work out “the financial terms and conditions of the surrogacy with the couple”.

11.1 ‘Surrogacy’ as a concept was elaborated upon in great detail by this Court in Baby Manji Yamada vs. Union of India, (2008) 13 SCC 518, wherein it was observed as follows:

“8. Surrogacy is a well-known method of reproduction whereby a woman agrees to become pregnant for the purpose of gestating and giving birth to a child she will not raise but hand over to a contracted party. She may be the child’s genetic mother (the more traditional form for surrogacy) or she may be, as a gestational carrier, carry the pregnancy to delivery after having been implanted with an embryo. In some cases surrogacy is the only available option for parents who wish to have a child that is biologically related to them.

9. The word “surrogate”, from Latin “subrogare”, means “appointed to act in the place of”. The intended parent(s) is the individual or couple who intends to rear the child after its birth.

10. In traditional surrogacy (also known as the Straight method) the surrogate is pregnant with her own biological child, but this child was conceived with the intention of relinquishing the child to be raised by others; by the biological father and possibly his spouse or partner, either male or female. The child may be conceived via home artificial insemination using fresh or frozen sperm or impregnated via IUI (intrauterine insemination), or ICI (intracervical insemination) which is performed at a fertility clinic.

11. In gestational surrogacy (also known as the Host method) the surrogate becomes pregnant via embryo transfer with a child of which she is not the biological mother. She may have made an arrangement to relinquish it to the biological mother or father to raise, or to a parent who is themselves unrelated to the child (e.g. because the child was conceived using egg donation, germ donation or is the result of a donated embryo). The surrogate mother may be called the gestational carrier.

12. Altruistic surrogacy is a situation where the surrogate receives no financial reward for her pregnancy or the relinquishment of the child (although usually all expenses related to the pregnancy and birth are paid by the intended parents such as medical expenses, maternity clothing, and other related expenses).

13. Commercial surrogacy is a form of surrogacy in which a gestational carrier is paid to carry a child to maturity in her womb and is usually resorted to by well-off infertile couples who can afford the cost involved or people who save and borrow in order to complete their dream of being parents. This medical procedure is legal in several countries including in India where due to excellent medical infrastructure, high international demand and ready availability of poor surrogates it is reaching industry proportions. Commercial surrogacy is sometimes referred to by the emotionally charged and potentially offensive terms “wombs for rent”, “outsourced pregnancies” or “baby farms”.

14. Intended parents may arrange a surrogate pregnancy because a woman who intends to parent is infertile in such a way that she cannot carry a pregnancy to term. Examples include a woman who has had a hysterectomy, has a uterine malformation, has had recurrent pregnancy loss or has a health condition that makes it dangerous for her to be pregnant. A female intending parent may also be fertile and healthy, but unwilling to undergo pregnancy.

15. Alternatively, the intended parent may be a single male or a male homosexual couple.

16. Surrogates may be relatives, friends, or previous strangers. Many surrogate arrangements are made through agencies that help match up intended parents with women who want to be surrogates for a fee. The agencies often help manage the complex medical and legal aspects involved. Surrogacy arrangements can also be made independently. In compensated surrogacies the amount a surrogate receives varies widely from almost nothing above expenses to over $30,000. Careful screening is needed to assure their health as the gestational carrier incurs potential obstetrical risks.”

11.2 The first move towards the prohibition of commercial surrogacy came with the 228th Report of the Law Commission of India in 2009, which flagged the problem of India becoming a “reproductive tourism destination” (i.e., foreign couples come to India for cost-effective surrogacy procedures) and wombs being “on rent”. It concluded with the following recommendations, inter alia:

“1. Surrogacy arrangement will continue to be governed by contract amongst parties, which will contain all the terms requiring consent of surrogate mother to bear child, agreement of her husband and other family members for the same, medical procedures of artificial insemination, reimbursement of all reasonable expenses for carrying child to full term, willingness to hand over the child born to the commissioning parent(s), etc. But such an arrangement should not be for commercial purposes.

2. A surrogacy arrangement should provide for financial support for surrogate child in the event of death of the commissioning couple or individual before delivery of the child, or divorce between the intended parents and subsequent willingness of none to take delivery of the child.

3. A surrogacy contract should necessarily take care of life insurance cover for surrogate mother.

4. One of the intended parents should be a donor as well, because the bond of love and affection with a child primarily emanates from biological relationship. Also, the chances of various kinds of child-abuse, which have been noticed in cases of adoptions, will be reduced. In case the intended parent is single, he or she should be a donor to be able to have a surrogate child. Otherwise, adoption is the way to have a child which is resorted to if biological (natural) parents and adoptive parents are different.

5. Legislation itself should recognize a surrogate child to be the legitimate child of the commissioning parent(s) without there being any need for adoption or even declaration of guardian.

6. The birth certificate of the surrogate child should contain the name(s) of the commissioning parent(s) only.

7. Right to privacy of donor as well as surrogate mother should be protected.

8. Sex-selective surrogacy should be prohibited.

9. Cases of abortions should be governed by the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act 1971 only.”

11.3 The question of age restrictions on the intending couple did not arise in these prior frameworks and recommendations. For instance, the ART (Regulation) Bill, 2008 imposed an age bracket of 21-45 years within which one could become a surrogate mother. However, there were no similar restrictions on the commissioning/intending couple. It is only with the advent of the Act in the year 2022 that the age-restrictions in Section 4(iii)(c)(I) have been created. Prior to the Act therefore, in the absence of a legal bar, or for that matter any binding surrogacy regulations, intending couples were free to bear children through surrogacy procedures irrespective of their age.

Surrogacy as an Exercise of Reproductive Autonomy:

12. In recent jurisprudence, the Supreme Court has often recognised that ‘reproductive autonomy’ is part of the constellation of rights afforded to all people under Article 21 of the Constitution. In 2009, a three-judge bench of this Court in Suchita Srivastava vs. Chandigarh Admn., (2009) 9 SCC 1 (“Suchita Srivastava”) observed as follows:

“22. There is no doubt that a woman’s right to make reproductive choices is also a dimension of `personal liberty’ as understood under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. It is important to recognise that reproductive choices can be exercised to procreate as well as to abstain from procreating. The crucial consideration is that a woman’s right to privacy, dignity and bodily integrity should be respected. This means that there should be no restriction whatsoever on the exercise of reproductive choices such as a woman’s right to refuse participation in sexual activity or alternatively the insistence on use of contraceptive methods.”

12.1 In K.S. Puttaswamy (Privacy-9J.) vs. Union of India, (2017) 10 SCC 1, which a recognised a right to privacy within the contours of Article 21, Dr. D.Y. Chandrachud, J. (as he then was), observed as follows:

“248. Privacy has distinct connotations including (i) spatial control; (ii) decisional autonomy; and (iii) informational control. [ Bhairav Acharya, “The Four Parts of Privacy in India”, Economic & Political Weekly (2015), Vol. 50 Issue 22, at p. 32.] Spatial control denotes the creation of private spaces. Decisional autonomy comprehends intimate personal choices such as those governing reproduction as well as choices expressed in public such as faith or modes of dress.”

12.2 Indeed, the freedom to make procreative choices as a facet of a right to privacy was recognised even as far back as this Court’s judgement in R. Rajagopal vs. State of T.N., (1994) 6 SCC 632, in which it was observed that “any right to privacy must encompass and protect the personal intimacies of the home, the family, marriage, motherhood, procreation and child-rearing”.

12.3 It would also be apt to refer to the more recent judgement of a three-judge bench of this Court in X2 vs. State, authored by Dr. D.Y. Chandrachud, CJ., where it was observed as under:

“101. The ambit of reproductive rights is not restricted to the right of women to have or not have children. It also includes the constellation of freedoms and entitlements that enable a woman to decide freely on all matters relating to her sexual and reproductive health. Reproductive rights include the right to access education and information about contraception and sexual health, the right to decide whether and what type of contraceptives to use, the right to choose whether and when to have children, the right to choose the number of children, the right to access safe and legal abortions, and the right to reproductive healthcare. Women must also have the autonomy to make decisions concerning these rights, free from coercion or violence.”

12.4 As recently as 2024, this Court in A vs. State of Maharashtra, (2024) 6 SCC 327 held that “(the right to choose and) reproductive freedom is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution”.

12.5 The 228th Report of the Law Commission of India (supra), opined that “if reproductive right gets constitutional protection, surrogacy which allows an infertile couple to exercise that right also gets the same constitutional protection”. Indeed, before the enforcement of the Act in the year 2022, we observe that this was the case. The choice of a couple, medically incapable of conceiving/bearing children naturally, to pursue surrogacy procedures to procreate in the absence of binding regulations was but an exercise of their decisional and reproductive autonomy. The Act has the object of regulating surrogacy so as to protect it from commercial exploitation. The object of the Act is not to frustrate the rights of intending couples who are otherwise eligible to undertake surrogacy procedures.

12.6 Therefore, at the time that intending couple Nos.1 to 3 herein generated and froze their embryos, they had qualified for surrogacy under the prevailing law. Thus, they came to possess a right to surrogacy as a part of reproductive autonomy and parenthood. Before 25.01.2022, we find that there were no binding laws, certifications, etc. regarding age restrictions on intending couples wishing to avail surrogacy (such as intending couple Nos.1 to 3 herein). Therefore, for couples above the (statutory) age limits under the Act, the right to access surrogacy or their entitlement to surrogacy was not conditional on their age and was freely available to couples under the prevailing law.

12.7 To reiterate, we are concerned solely with the question of age-restrictions in these three cases. The short point is, that on the issue of age alone, the right to surrogacy as a facet of autonomy under Article 21 was unrestricted prior to the enforcement of the Act under consideration. In other words, the right to decide that despite one’s age, one wishes to have children through surrogacy, was afforded to intending couples under Article 21 prior to the enforcement of the Act. Now with the enforcement of the Act, can that right be stultified?

Retrospective Application of Age-Restrictions:

13. In the case of intending couple Nos.1 to 3, they had exercised this decisional autonomy and commenced the process of surrogacy, to the extent of freezing their embryos in preparation for transfer to the womb of the surrogate mother. They were at the last step of Stage A as per the diagram (supra).

13.1 Therefore, the real issue is whether a statutory regulation may apply retrospectively and frustrate a right which had and has the imprimatur of the Constitution under Article 21 and had been exercised by intending couples who had commenced the process of surrogacy prior to the enforcement of the Act.

13.2 Ms. Aishwarya Bhati, learned ASG argued that the agerestrictions under the Act should apply retrospectively to such couples also since the State has an interest in ensuring that children born to such parents receive adequate parenting. Put simply, the submission was that intending couples, one or both of whom are above the prescribed age-limit(s) under the Act, will not be able to effectively parent their children.

13.3 We are unable to accept this submission. In Suchita Srivastava, this Court observed in the case of a pregnant rape victim that also suffered from mental retardation, that “(the victim’s) reproductive choice should be respected in spite of other factors such as the lack of understanding of the sexual act as well as apprehensions about her capacity to carry the pregnancy to its full term and the assumption of maternal responsibilities thereafter”.

13.4 In the present case, the parenting capabilities of the couple are being used to assail their eligibility to have children through surrogacy. The above observations in Suchita Srivastava would apply squarely to such a case as well. It is not for the State to question the couple’s ability to parent children after they had begun the exercise of surrogacy when there were no restrictions on them to do so.

13.5 In this regard, we consider it useful to note that the law does not impose any age restrictions on couples who wish to conceive and bear children naturally. In this regard, prior to the enforcement of the Act, intending couple Nos.1 to 3 were on the same footing as couples who wished to conceive naturally. But, the stark distinction is that owing to medical reasons/disadvantages, they could not have children naturally. Having exercised this parity in freedom by commencing the surrogacy process, can it be said that they can now be denied the continued exercise of this freedom only because of the age bar under the Act? We are not inclined to believe so.

13.6 Learned ASG for the respondent-Union of India also argued that the age-limits should be applied retrospectively due to concerns over the declining quality of gametes with age and the potential impact of the same on the children born through surrogacy. However, we are also not inclined to accept this submission for the same reasons as above. Whatever be the restrictions post the enforcement of the Act, the fact remains that prior to 25.01.2022, intending couple Nos.1 to 3 were not restricted by their age and had duly commenced the surrogacy process using their freedom. On the basis of concerns over gamete quality, the law does not fetter couples who wish to bear children naturally. Prior to the enforcement of the Act, the law did not fetter intending couple Nos.1 to 3 on this ground either. Moreover, there is no age bar for couples who wish to adopt children under the provisions of the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956, which personal law applies to the intending couples herein.

13.7 We must clarify that we are not questioning the wisdom of the Parliament in its prescription of age-limits under the Act, or passing a judgement on its validity. Rather, the cases before us are limited to couples who commenced the surrogacy process before the enforcement of the Act, and we limit our observations to the same. Therefore, the question that arises is, whether, the respondent- Union of India has been able to demonstrate compelling reasons as to why the age-limits must apply retrospectively and why the freedom of intending couple Nos.1 to 3 to pursue surrogacy, once exercised by them, should now be taken away. Concerns over parenting and gamete quality, while possibly being legitimate concerns for lawmakers (though we do not express any opinion on the same), are not compelling reasons for retrospective application of the Act, especially since the State allows some categories of couples (those who wish to conceive naturally) to procreate despite these concerns or for that matter to opt for adoption as per personal law.

13.8 In this regard, we find force in the submissions of learned senior counsel and counsel for the petitioners that the right to surrogacy vested in intending couple Nos.1 to 3 prior to the enforcement of the Act, it was a constitutionally recognized right which continues to be so recognized but subject to reasonable restrictions with a view to obviate exploitation of surrogate mothers through a process of commercial surrogacy. Therefore, such a constitutional right cannot be taken away retrospectively from them on account of their age, without an express intention to do so under the Act. The judgements of this Court in S.L. Srinivasa Jute Twine Mills and Gopinathan Nair squarely apply in the cases before us. In the first of the aforesaid cases, it was observed in paragraph 18 as under:

“18. It is a cardinal principle of construction that every statute is prima facie prospective unless it is expressly or by necessary implication made to have retrospective operation. (See Keshavan Madhava Menon v. State of Bombay [1951 SCC 16 : 1951 SCR 228 : AIR 1951 SC 128: 1951 Cri LJ 860] .) But the rule in general is applicable where the object of the statute is to affect vested rights or to impose new burdens or to impair existing obligations. Unless there are words in the statute sufficient to show the intention of the legislature to affect existing rights, it is deemed to be prospective only nova constitutio futuris formam imponere debet, non praeteritis. In the words of Lord Blanesburgh,

“provisions which touch a right in existence at the passing of the statute are not to be applied retrospectively in the absence of express enactment or necessary intendment” (see Delhi Cloth & General Mills Co. Ltd. v. CIT [AIR 1927 PC 242 : 54 IA 421] , AIR p. 244).

“Every statute, it has been said”, observed Lopes, L.J.,

“which takes away or impairs vested rights acquired under existing laws, or creates a new obligation or imposes a new duty, or attaches a new disability in respect of transactions already past, must be presumed to be intended not to have a retrospective effect.” (See Amireddi Rajagopala Rao v. Amireddi Sitharamamma [(1965) 3 SCR 122 : AIR 1965 SC 1970] .) [Ed. : But see fn. 27, p. 402 of Principles of Statutory Interpretation, by Justice G.P. Singh, 8th Edn. (Reprint) 2002.]

As a logical corollary of the general rule, that retrospective operation is not taken to be intended unless that intention is manifested by express words or necessary implication, there is a subordinate rule to the effect that a statute or a section in it is not to be construed so as to have larger retrospective operation than its language renders necessary. (See Reid v. Reid [(1886) 31 Ch D 402 : 54 LT 100 (CA)] .) In other words, close attention must be paid to the language of the statutory provision for determining the scope of the retrospectivity intended by Parliament. (See Union of India v. Raghubir Singh [(1989) 2 SCC 754 : AIR 1989 SC 1933] .) The above position has been highlighted in Principles of Statutory Interpretation by Justice G.P. Singh. (10th Edn., 2006 at pp. 474 and 475.)”

13.9 It is important to note in this regard, that the relevant agelimits under the Act are imposed on the intending couples in the present cases. Therefore, they are in the nature of fetters on the freedom of choice and the realm of decision-making that, in the absence of regulation, would be the sole prerogative of intending couples. For intending couples who undertook surrogacy procedures prior to the Act, age-related considerations were entirely their prerogative and as explained earlier, an exercise of their rights under Article 21 of the Constitution. Therefore, we have no hesitation in observing that the right to make autonomous decisions regarding the age at which one wished to pursue surrogacy, had vested in intending couple Nos.1 to 3. Hence, since there is no manifest intention in the provisions of the Act to apply the age-limits retrospectively, we are of the view that the same is not permissible. Further, the intending couples in the present cases could have opted for adoption of children under personal law in the absence of an age restriction. In such a situation, the argument regarding quality parenting would be futile and of no consequence.

13.10 In this regard, it is helpful to refer to the Statement of Objects and Reasons in the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2019, relevant parts of which are reproduced below:

“India has emerged as a surrogacy hub for couples from different countries for past few years. There have been reported incidents of unethical practices, exploitation of surrogate mothers, abandonment of children born out of surrogacy and import of human embryos and gametes. Widespread condemnation of commercial surrogacy in India has been regularly reflected in different print and electronic media for last few years. The Law Commission of India has, in its 228th Report, also recommended for prohibition of commercial surrogacy by enacting a suitable legislation. Due to lack of legislation to regulate surrogacy, the practice of surrogacy has been misused by the surrogacy clinics, which leads to rampant of commercial surrogacy and unethical practices in the said area of surrogacy.

2. In the light of above, it had become necessary to enact a legislation to regulate surrogacy services in the country, to prohibit the potential exploitation of surrogate mothers and to protect the rights of children born through surrogacy.”

13.11 The common thread that runs through the emphasised portions above is that they express the need for surrogacy regulation in terms of impacts on people who are different from the intending couple – exploitation of the surrogate mother and the rights (pertinently the protection against abandonment) of children born through surrogacy. These considerations have manifested in various provisions of the Act, such as the prohibition of commercial surrogacy [Section 4(ii)(c)]; the prohibition on surrogacy clinics, inter alia, inducing a woman to act as a surrogate mother [Section 3(v)(b)]; the prohibition on abandonment of the child (Section 7); the right of a child to be deemed a ‘biological child’ of the intending couple (Section 8), etc.

13.12 Thus, prior to the enforcement of the Act, the right to pursue surrogacy despite one’s age, did not impinge on any of the above considerations and was solely in the decision-making domain of the intending couple. It was a personal decision, with personal consequences. Although the respondent-Union of India has argued that the age-limits are directly related to the welfare of the children, as explained above, we are unable to accept this submission in view of the unlimited freedom afforded to couples who wish to conceive children naturally, irrespective of their age. This was also the status occupied by intending couple Nos.1 to 3 before the enforcement of the Act. Their decision to have children through surrogacy despite their age was a personal one and did not involve a third person (the surrogate mother) or the rights of the children to be considered biological children.

13.13 Therefore, we are of the view that the right to decide to bear children through surrogacy despite their ages, is one that can legitimately be considered to have vested in intending couple Nos.1 to 3 herein prior to the coming into force of the Act, following their decision to undertake the surrogacy procedure. At this point, we must once again reiterate that our decision is restricted to intending couple Nos.1 to 3, who have been prevented from pursuing surrogacy solely due to their age, despite having commenced the surrogacy procedure before the enforcement of the Act. We make it clear that have not considered the vires of the age fixation under Section 4 for intending couples in this order.

‘Commencement’ of the Surrogacy Procedure:

14. The next question that arises is the proper meaning of the term ‘commencement’ of the surrogacy procedure. When can it be said that couples have ‘commenced’ the process of surrogacy before the enforcement of the Act, and hence may be allowed to continue despite the subsequent age-limits? In this regard, we find it helpful to refer to the diagram submitted by the respondent-Union of India, referred to in an earlier paragraph of this order.

14.1 We can see that the last step in Stage A is the ‘freezing of embryos’, which marks the last step before the commencement of Stage B, which involves the surrogate mother inasmuch as the embryos are transferred to the uterus of the surrogate mother by implantation. At this point, the intending couple has already completed the process of extracting gametes which included both the sperm and oocyte; fertilising them to form zygotes, and freezing the resulting ‘embryos’, which means a developing or developed organism after fertilization till the end of fifty-six days. Section 2(c) defines “fertilisation” to mean the penetration of the ovum by the spermatozoan and fusion of genetic materials resulting in the development of a zygote. The word ‘zygote’ is defined in Section 2(zh) to mean the fertilised oocyte prior to the first cell division. Further, from the fifty-seventh day after fertilization onwards, the organism is called a ‘foetus’ which is defined to mean a human organism during the period of its development beginning on the fifty-seventh day following fertilisation or creation (excluding any time in which its development has been suspended) and ending at birth.

This is the stage at which intending couple Nos.1 to 3 found themselves before the commencement of the Act. They were thus ready to transfer the embryo to the womb of the surrogate mother.

14.2 Now, if the transfer to the womb had been effected before the commencement of the Act, then Section 53 would have operated as a ‘gestational’ (transitional) period to the benefit of the surrogate mother in which the age restrictions on the intending couple would not have applied at all. Therefore, even if a surrogate child is born within ten months after the Act is enforced then the age bar would not apply insofar as the intending couples are concerned. Hence, the submission of learned ASG is that the age-limits can be transgressed only when the surrogate mother has been introduced into the surrogacy procedure. However, we do not find this to be a valid argument. This would mean that even if the intending couple had crossed the age restriction prior to the enforcement of the Act, and the transitional provision applied, the concerns of them being too old to have children and concerns regarding the quality of their parenting would vanish and be disregarded. Such a position cannot be accepted as the same in effect frustrates the right of intending couples attempting to have a surrogate child, which is a constitutional right regulated by statute. Hence, there is a need to strike a balance between the provision regarding the age restriction, the transitional provision (Section 53 of the Act) and the rights of the intending couples to have a surrogate child when they had commenced the surrogacy procedure prior to the commencement of the Act and were in the midst of the said procedure when the Act has placed age restrictions on them. In the instant case, the intending couples were a step away from involving the surrogate mother in the process.

14.3 Therefore, we deem it appropriate to observe that the ‘commencement’ of the surrogacy process for the limited purpose of determining when the age-limits under the Act must be applied prospectively and not retrospectively takes place after the intending couple has completed the extraction and fertilisation of gametes and has frozen the embryo with an intention to and for the purposes of, transfer to the womb of the surrogate mother. There is no additional step to be undertaken by the couple themselves. All subsequent steps would involve only the surrogate mother. There is nothing else for the couple to do by themselves, that would strengthen the manifestation of their intention to pursue surrogacy. Therefore, the freezing of embryos for the purpose of surrogacy is a stage at which one can say that the intending couple has taken multiple bona fide steps and had manifested their intention to pursue surrogacy and all that remained was involvement of the surrogate mother herself in Stage B of the diagram, which could not be gone through due to various circumstances including the intervention of Covid-19 Pandemic in these cases.

14.4 We also wish to refer in an analogous way to the relevant portion of an earlier order of this Court (B.V. Nagarathna and Ujjal Bhuyan, JJ.) dated 18.10.2023 in the main Writ Petition, i.e., Arun Muthuvel vs. Union of India and Ors., WP (Civil) No.756 of 2022. This was in the context of an amendment made to Form 2 (disallowing the use of donor gametes) and the other provisions of the Surrogacy Act and Rules, which can be extracted as under:

“Secondly, the petitioner herein had commenced the procedure for achieving parenthood through surrogacy much prior to the amendment which has come into effect from 14.03.2023. Therefore, the amendment which is now coming in the way of the intending couple and preventing them from achieving parenthood through surrogacy, we find, is prima facie contrary to what is intended under the main provisions of the Surrogacy Act both in the form as well as in substance.”

However, the point on ‘commencement of surrogacy prior to the amendment’ is mentioned only briefly in the order, while considering the question regarding the dissonance between the impugned amendment to Form 2, and Rule 14(a) of the Surrogacy Rules.

Operation of a statute:

15. The controversy in this case really revolves around the concept of operation of statutes under principles of statutory interpretation. This is because the Act has been enforced with effect from 25.01.2022 mandating certain requirements to be fulfilled by the intending couples, one of which is the requirement of age. As already noted, the petitioners and applicant herein contend that they have commenced the surrogacy procedure prior to the commencement of the Act and therefore, the same cannot now be frustrated on the basis of age restrictions imposed under Section 4(iii)(c)(I) of the Act. Hence, the point for consideration is, whether, the operation of the Act is retrospective in nature so as to encompass intending couple Nos.1, 2 and 3, or whether, the mandatory requirements under the Act would only apply prospectively from the date of the enforcement of the Act, i.e., when the surrogacy procedure is commenced on or after 25.01.2022.

15.1 We observe that a piece of Central Legislation comes into operation on the day it receives Presidential assent and is generally construed as coming into operation immediately on the expiration of the day preceding its commencement. Thus, in the instant case, the Act has come into operation on the midnight between 24.01.2022 and 25.01.2022. Further, the Parliament as well as the State Legislatures have the plenary powers to make laws both prospectively as well as retrospectively. By retrospective legislation, the Parliament or a Legislature may make a law which is operative for a limited period prior to the date of its coming into force. This power is generally used for validating prior executive and legislative acts by retrospectively curing the defects which led to the invalidity and thus, making ineffective judgments of competent courts declaring the invalidity.

15.2 Another cardinal principle of construction is that every statute is generally prospective unless it is made retrospective either expressly or by necessary implication vide State of Bombay vs. Vishnu Ramchandra, AIR 1961 SC 307 (“Vishnu Ramchandra”); Zile Singh vs. State of Haryana, AIR 2004 SC 5100 (“Zile Singh”).

Thus, a new law ought to regulate what is to follow and not the past. This is a presumption of prospectivity which is expressed in the legal maxim, nova constitutio futuris formam imponere debet non praeteritis. Thus, the presumption operates unless the contrary is expressed in the statute itself or is otherwise discernible by necessary implication vide Monnet Ispat & Energy Ltd. vs. Union of India, (2012) 11 SCC 1. In other words, a right in existence at the passing of the statute cannot be impacted by its provisions retrospectively in the absence of an express enactment or necessary intendment. Thus, any statute which takes away or impairs vested rights acquired under existing laws or, inter alia, attaches a new disability in respect of transaction already passed, must be presumed to be intended not to have a retrospective effect. Therefore, a statute cannot be construed to have a retrospective operation than what the language desires it to be necessary. Further, a statute need not have an express provision to make it retrospective as by necessary implication a statute can have a retrospective operation depending on the use of legal fiction or by necessary implication.

15.3 Another principle flowing from presumption against retrospectivity is that “one does not expect rights conferred by the statute to be destroyed by events which took place before it was passed”.

15.4 In contrast to statutes dealing with substantive rights, statutes dealing merely with matters of procedure are presumed to be retrospective unless such a construction is textually inadmissible vide Hitendra Vishnu Thakur vs. State of Maharashtra, AIR 1994 SC 2623 (“Hitendra Vishnu Thakur”). It has been said that law relating to forum and limitation is procedural in nature whereas law relating to right of action and right of appeal even though remedial is substantive in nature; that procedural statute should not generally speaking be applied retrospectively where the result would be to create new disabilities or obligations or to impose new duties in respect of transactions already accomplished; that statute which not only changes the procedure but also creates new rights and obligations shall be construed to be prospective unless otherwise provided either expressly or by necessary implication vide Hitendra Vishnu Thakur.

15.5 The classification of a statute as either substantive or procedural does not necessarily determine whether it may have a retrospective operation. For example, a statute of limitation is generally regarded as procedural but if its application to a past cause of action has the effect of reviving or extinguishing a right of suit, such an operation cannot be said to be merely procedural. For these reasons the rule against retrospectivity has also been avoiding the classification of statutes into substantive and procedural and avoiding use of words like existing or vested. One such formulation by Dixon, C.J. is in Maxwell vs. Murphy, (1957) 96 CLR 261, page No. 267 which is as follows:

“The general rule of the common law is that a statute changing the law ought not, unless the intention appears with reasonable certainty, to be understood as applying to facts or events that have already occurred in such a way as to confer or impose or otherwise affect rights or liabilities which the law had defined by reference to the past events. But, given rights and liabilities fixed by reference to the past facts, matters or events, the law appointing or regulating the manner in which they are to be enforced or their enjoyment is to be secured by judicial remedy is not within the application of such a presumption.”

15.6 Another more simple statement of the rule was made in Secretary of State for Social Security vs. Tunnicliff, (1991) 2 All ER 712 by Staughton LJ in the following words:

“The true principle is that Parliament is presumed not to have intended to alter the law applicable to past events and transactions in a manner which is unfair to those concerned in them unless a contrary intention appears. It is not simply a question of classifying an enactment as retrospective or not retrospective. Rather it may well be a matter of degree – the greater the unfairness, the more it is to be expected that Parliament will make it clear if that is intended.”

The above statement was approved by the House of Lords in L’office Cherifien des Phosphates vs. Yamashita Shinnihon Steamship Co. Ltd., (1994) 1 All ER 20. It was observed that the question of fairness will have to be answered in respect of a particular statute by taking into account various factors, viz., value of the rights which the statute affects; extent to which that value is diminished or extinguished by the suggested retrospective effect of the statute; unfairness of adversely affecting the rights; clarity of the language used by Parliament and the circumstances in which the legislation was created.

15.7 All these factors must be weighed together to provide a direct answer to the question whether the consequences of reading the statute with the suggested degree of retrospectivity is so unfair that the words used by Parliament could not have been intended to mean what they might appear to say. (Source: G.P. Singh’s Principles of Statutory Interpretation, 15th Edition)