Analysis

The right to life and personal liberty under Article 21: A timeline

50 years since the Emergency, SCO traces the Court’s gradual expansion of the right to life and personal liberty

1950

A.K. Gopalan v State of Madras

Text: The phrase “procedure established by law” under Article 21 was interpreted by a 5:1 majority to mean state-enacted law that need not reflect principles of natural justice. Preventive detention was held constitutionally permissible, subject to limited procedural safeguards, and not reviewable under the broader set of fundamental rights. The judgement was overruled by a 7 judge bench decision in Maneka Gandhi v Union of India.

1954

M.P. Sharma v Satish Chandra

In one of the earliest cases addressing the right to privacy in India, the Supreme Court noted that the Constitution does not contain a provision similar to the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution, which protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. Consequently, the Court ruled that the government’s authority to conduct search and seizure could not be challenged on the basis of a right to privacy.

1962

Kharak Singh v State of Uttar Pradesh

The Supreme Court held that the right to privacy is not explicitly guaranteed under the Constitution; however, the concept of “personal liberty” under Article 21 is broad and includes a range of rights not covered by Article 19(1). The term “life” under Article 21 was interpreted to mean more than mere animal existence, including the full enjoyment of bodily and personal integrity.

The Court invalidated surveillance under the UP Police Regulation and held unauthorised domiciliary visits to violate personal liberty. But it didn’t strike down the part of the regulation that permitted the shadowing of history-sheeters.

Justices Subba Rao and J.C. Shah, however, disagreed with the majority, holding that Article 21 safeguards individuals from both direct and indirect encroachments. They also found that the Regulation violated the freedoms of expression and movement. On these grounds, they held the entirety of the Regulation to be invalid. Their dissent was later endorsed in Maneka Gandhi.

1965

State of Maharashtra v Prabhakar Pandurang Sangzgiri

The Supreme Court held that the conditions under the Bombay Conditions of Detention Order, 1951 define the lawful scope of restricting a detainee’s personal liberty and are not mere privileges. Since the Order did not prohibit writing or publishing a book, the State’s refusal to allow it violated the detainee’s personal liberty under Article 21. Even during a situation of Emergency, the Court noted, Article 359 does not bar courts from intervening if the detention is in contravention of the prescribed law.

1970

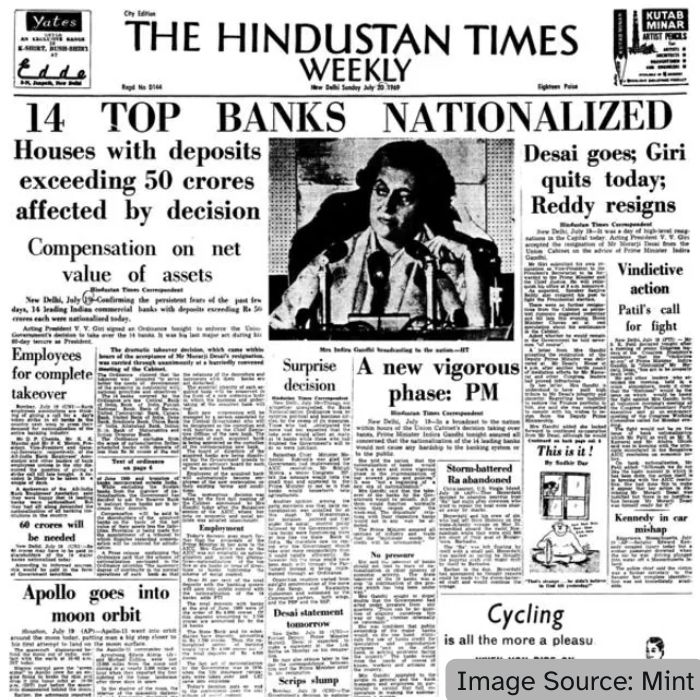

R.C. Cooper v Union of India

A 11-judge Bench of the Supreme Court held that Article 21 takes the form of specific restrictions on State action, legislative and executive, to ensure protection of individual rights. A 10:1 majority interpreted ‘law’ to mean “a law which is within the competence of the Legislature, and does not impair the guarantee of the rights in Part III”, departing from the interpretation of ‘procedure established by law’ under Article 21 in A.K. Gopalan v State of Madras.

1973

Sambhu Nath Sarkar v State of West Bengal

Text: A 7-judge Bench of the Supreme Court dealt with a challenge to the Maintenance of Internal Security Act, 1971. The Court found Section 17-A of the Act unconstitutional on the ground of violation of Article 22(7). Observing that Article 21 guarantees safeguards against arbitrary deprivation of life and personal liberty, except through a procedure established by law, the judgement underscored the importance of procedural safeguards in the context of preventive detention laws.

1974

D. Bhuvan Mohan Patnaik v State of Andhra Pradesh

A three-judge Bench observed that even convicts cannot be denied the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21, except by a procedure established by law. Some freedoms already stand curtailed by reason of imprisonment. Therefore, the right of personal liberty must not be totally denied to a convict during the period of incarceration. The right to personal liberty is to be balanced with security measures.

1976

ADM Jabalpur v Shivkant Shukla

The Supreme Court, in a 4:1 majority, held that no person has any locus to claim Article 21 protections if an Emergency under Article 359 is in force, even if they have been illegally detained. The majority ruled that fundamental rights are not absolute and can be limited to balance competing claims. The Court noted that exceptional circumstances allow the exercise of extraordinary powers and at times, individual liberty must yield to the broader interests of the State. Justice H.R. Khanna, in a famous dissent, held that the right to life is not a gift of the Constitution and cannot be suspended.

1978

Maneka Gandhi v Union of India

Overruled Gopalan. Held that “procedure established by law” must be fair, just and reasonable. The right to travel outside the country was held to be included in the right to personal liberty. Article 21 was held to not be just a negative restriction on State action but also a recognition of the broad scope of personal liberty it protects. Any restriction on rights under Article 21 must also meet the tests of fairness and reasonableness under Articles 14 and 19.

1979

Hussainara Khatoon (V) v Home Secy., State of Bihar

A three-judge Bench dealt with the rights of undertrials under Article 21. Directing the release of 59 undertrial prisoners, the Supreme Court observed that pre-trial detention exceeding the maximum sentence was violative of Article 21.

Further, even a failure to provide free legal services to indigent accused could amount to a violation of Article 21. The Supreme Court also held that the State cannot deny the constitutional right to a speedy trial.

1981

Francis Coralie Mullin v Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi

Personal liberty under Article 21 was given wide amplitude and held to include a variety of rights, some of which also receive independent protection under Article 19. Importantly, any deprivation of liberty must be under a law that passes constitutional scrutiny. The Court held that preventive detention laws must satisfy the requirements not only of Article 22 but also Article 21.

1984

Saroj Rani v Sudarshan Kumar Chadha

The Supreme Court held that a decree for restitution of conjugal rights under Section 9 of the Hindu Marriage Act aimed to help spouses resolve marital disputes amicably and prevent the breakdown of marriage, thus serving a valid social purpose. It clarified that “conjugal rights” did not imply forced sexual cohabitation, but rather referred broadly to the marital relationship. The Court rejected the Andhra Pradesh High Court’s ruling in T. Sareetha, which had found Section 9 unconstitutional for infringing on sexual autonomy and privacy. Instead, it upheld the view expressed by the Delhi High Court in Harvinder Kaur, where the Bench had found that Section 9 did not violate Article 21.

1985

Olga Tellis v Bombay Municipal Corporation

The Court held that the sweep of the right to life under Article 21 encompasses not merely the negative limitation that life cannot be taken except according to procedure established by law but also includes positive entitlements essential for a dignified existence. A key facet of this right is the right to livelihood. The substance of a law cannot be divorced from its procedure. Thus, the constitutional mandate under Article 21 imposes a dual test of legality and reasonableness, ensuring that both the law and its implementation respect the fundamental values of fairness, justice and dignity.

1993

Unni Krishnan v State of Andhra Pradesh

The Court held that the citizens of India have a fundamental right to education, which emanates from Article 21. However, this right is not absolute, and its scope must be construed in light of Directive Principles of State Policy, especially Article 45 which urges the State to provide free education to all children under 14 years. For those above 14, the right would be subject to the State’s economic capacity and development, as per Article 41. The judgement consequently led to the 86th Constitutional Amendment in 2002 which introduced Article 21A making free and compulsory education a fundamental right for children between the ages of 6 and 14.

1994

R. Rajagopal v State of Tamil Nadu

The Court held that the right to privacy is implicit in Article 21 and includes a “right to be let alone.” It protects information about personal matters such as marriage, procreation and education from unauthorised publication, regardless of whether the content is truthful or critical. However, the Court clarified that this right is not absolute. If a person voluntarily enters public controversy or if the information published is drawn from the public record, the right to privacy may be limited. Moreover, public officials cannot claim privacy regarding acts relevant to official duties unless the publication is malicious or recklessly false. The Court emphasised that privacy claims can only arise after a violation and not in anticipation.

1996

People’s Union for Civil Liberties v Union of India

The Court held that telephone tapping constitutes a grave intrusion of an individual’s privacy. While it is acknowledged that every government, even a democratic one, may undertake covert operations as part of its intelligence framework, such actions must not override the citizen’s interest in privacy, which must be safeguarded against abuse by state authorities. The Court noted that Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 specified when phone tapping could be allowed but lacked proper procedural safeguards. Instead of striking it down, the Court upheld the provision and laid down detailed guidelines to regulate surveillance.

2010

Selvi v State of Karnataka

The Supreme Court examined the constitutional validity of investigative techniques such as narcoanalysis, brain mapping (BEAP) and polygraph tests. It held that the involuntary administration of these techniques amounts to testimonial compulsion, violating Article 20(3) as well as Article 21. The Court ruled that Article 20(3) must be interpreted in light of the broader protections offered by Article 21, including the right to a fair trial, mental privacy and substantive due process. The Court held that compelled extraction of physiological responses or drug-induced disclosures, without statutory basis or consent, is an unconstitutional intrusion into mental privacy.

2012

In Re: Ramlila Maidan Incident

The right to sleep, the Court held, is a fundamental right under Article 21, just like the rights to breathe, eat, drink, or blink. In this case, the Court found that the police action of forcibly evacuating a crowd while they were asleep, without adequate notice or an opportunity to leave peacefully, amounted to an illegitimate intrusion into their privacy. Such conduct violated their basic human right to sleep and was therefore unconstitutional.

2017

Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v Union of India

The Supreme Court unanimously held that the right to privacy is a fundamental right, protected as an essential aspect of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21, and as part of the broader guarantees under Part III of the Constitution. The Court overruled earlier decisions in M.P. Sharma and Kharak Singh, to the extent that they had denied constitutional recognition to privacy. Justice Chandrachud’s majority opinion expressly noted that the majority opinions in ADM Jabalpur are “seriously flawed” on the ground that the Constitution is not the “sole repository” of the right of life. The Court further emphasised the need for a comprehensive data protection law.

2017

Independent Thought v Union of India

The Supreme Court held that Exception 2 to Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC), which excluded marital intercourse with a minor wife between the ages of 15 and 18 from the definition of rape, must be read down to align with the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO) . This effectively raised the age of consent for marital sexual relations to 18 years, thus protecting the rights and bodily autonomy of married girl children. Emphasising Article 21, the Court observed that early marriage undermines a girl child’s dignity, self-esteem and bodily integrity.

2018

Joseph Shine v Union of India

The Supreme Court, in striking down Section 497 of the IPC (criminalisation of adultery) and the corresponding provision Section 198(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 held that these laws were unconstitutional as they violated Articles 14, 15 and 21. The Court rejected the idea that family structures could shield violations of fundamental rights, and condemned Section 497 for perpetuating gender inequality. The Judgement reaffirmed that sexual autonomy is an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21.

2018

Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India

The Supreme Court held that Section 377 of IPC was discriminatory against the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) community, recognising that sexual orientation is an intrinsic element of an individual’s identity, dignity and autonomy. It found that the provision violated the rights to dignity, privacy and sexual autonomy under Article 21, alongside other fundamental rights.

2018

Common Cause v Union of India

The Supreme Court held that the right to die with dignity is a fundamental right under Article 21, forming part of the right to live with dignity. It recognised that individuals with terminal illness or deteriorating health have the right to execute Advance Medical Directives or living wills, allowing them to make informed choices about end-of-life care. It held that continuing medical treatment against a patient’s wishes violates informed consent, bodily privacy and integrity, all of which are facets of the right to privacy under Article 21.

Central Public Information Officer, Supreme Court of India v Subhash Chandra Agarwal

2019

The Court noted that under the Right to Information Act, personal information is protected from unwarranted invasion of privacy but may be disclosed if a larger public interest justifies it. The Court further clarified that the right to privacy includes both quantitative and qualitative protections— covering what has already been disclosed and what remains private. The emphasis of privacy law lies not just in the content of the information, but in preventing illegal intrusions into private rights.

2021

Laxmibai Chandaragi B. v The State Of Karnataka

The Court held that when two consenting adults decide to marry, they do not need approval from their families or communities. It reaffirmed that the freedom to choose one’s spouse is a fundamental component of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21.

2022

X v Principal Secretary, Health and Family Welfare Department, Govt. of NCT of Delhi

The Court held that the right to privacy encompasses reproductive autonomy and includes a pregnant woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy due to changes in her marital status. It ruled that a narrow interpretation of Rule 3B of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules that excludes unmarried women would conflict with the legislative intent. The Court concluded that Rule 3B must be interpreted broadly to ensure that unmarried women are also entitled to access safe and legal abortions between 20 to 24 weeks of pregnancy.

2022

Jacob Puliyel vs. Union of India

The Supreme Court held that bodily integrity is protected under Article 21 and individuals cannot be forcibly vaccinated. The right to personal autonomy includes the freedom to refuse medical treatment, including vaccines. However, the Court also recognised that protecting public health is a legitimate State objective. It ruled that the Government may impose reasonable restrictions such as mandatory vaccination requirements in situations where refusal to vaccinate may endanger others, contribute to virus mutation or strain healthcare infrastructure.

2023

Indrakunwar v State of Chhattisgarh

The Supreme Court of India held that the right to privacy encompasses an accused person’s right to remain silent during a criminal trial. Accordingly, an accused’s silence about a personal aspect of their life cannot be considered an incriminating factor for a homicide conviction.

2023

Kaushal Kishor v State of Uttar Pradesh

The Court held that the scope of the ‘right to life’ has expanded over the years to encompass human dignity, the right to privacy and the right to be forgotten. Since non-State actors play significant roles in various aspects of life, the State has a positive obligation to safeguard the right to life from infringements by such entities.