Reserved Candidates in General Category Seats

Rajasthan High Court v Rajat Yadav

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that reserve category candidates who score above the cut-off mark for open category candidates cannot be denied equality of treatment merely on account of their caste or community.

The Rajasthan High Court had advertised 2756 vacancies for Junior Judicial Assistants, involving a written test followed by...

Case Details

Judgement Date: 19 December 2025

Citations: 2025 INSC 1503 | 2025 SCO.LR 12(5)[25]

Bench: Dipankar Datta J, A.G. Masih J

Keyphrases: The Rajasthan District Courts Ministerial Establishment Rules, 1986—Recruitment to the post of Junior Judicial Assistant/Clerk Grade-II—Reservations—Cut-off marks for reserved candidates higher than general candidates—Reserved candidates who outperformed general candidates denied selection—High Court declares exclusion discriminatory—Supreme Court upholds judgement.

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

DIPANKAR DATTA, J

THE APPEALS

1. A Division Bench of the High Court of Judicature for Rajasthan, Bench at Jaipur, allowed D.B. Civil Writ Petition No. 7564 of 2023 and connected matters vide judgment and order dated 18th September, 20231. Aggrieved by the impugned order, the administration of the High Court and its Registrar2 have preferred these civil appeals by special leave.

BRIEF RESUME OF FACTS

2. The basic facts triggering the appellate proceedings before us are undisputed.

3. The Rajasthan District Courts Ministerial Establishment Rules, 1986 were framed to regulate appointments and conditions of service in the ministerial establishments of the District Courts. Thereafter, the Rajasthan High Court Staff Service Rules, 2002 were notified on 5th December, 2002, providing for recruitment to the post of Junior Judicial Assistant/Clerk Grade-II by way of a competitive examination comprising two stages, viz. a written test and a computer-based typewriting test.

4. In pursuance thereof, on 5th August, 2022, the High Court issued an advertisement. Applications were invited for appointment on 2756 vacancies in the posts of Junior Judicial Assistant/Clerk Grade-II in the High Court, the Rajasthan State Judicial Academy, the District Courts and allied institutions, including the Legal Services Authorities and Permanent Lok Adalats. The vacancies were distributed category-wise across General, Scheduled Caste (SC), Scheduled Tribe (ST), Other Backward Class (OBC), Most Backward Class (MBC), Economically Weaker Section (EWS), and horizontal reservation for various other categories.

5. The scheme of selection envisaged a written test of 300 marks, followed by a typewriting test on computer of 100 marks. The qualifying marks in the written test were fixed at 50% for the General category, 45% for OBC and other categories, and 40% for SC/ST/PwD3. It was further stipulated that only candidates securing the prescribed minimum in the written test, to the extent of five times the number of vacancies category-wise, would be eligible to appear in the typewriting test. The final merit list was to be drawn on the aggregate of marks secured by the aspirants at both stages.

6. The respondents in these appeals had applied pursuant to the aforementioned advertisement. Since they were found prima facie eligible, the appellants permitted them to appear in the written test.

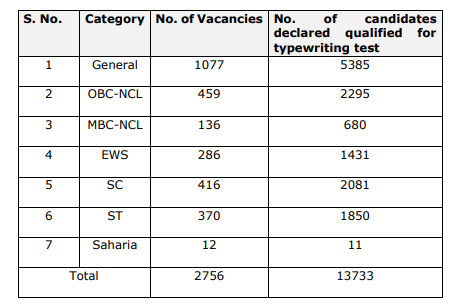

7. The written test was held on 12th and 19th March, 2023. The respondents duly participated in the written test. The results followed soon, being declared on 1st May, 2023. The list of candidates who qualified for the second stage of the examination, i.e., the typewriting test on computer, was duly published. The break-up of candidates called for the type-writing test, which was thereafter scheduled between 26th May and 29th May, 2023, is given in the chart hereinbelow

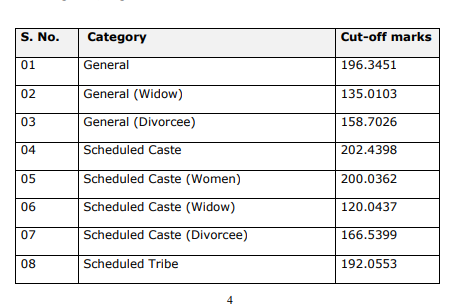

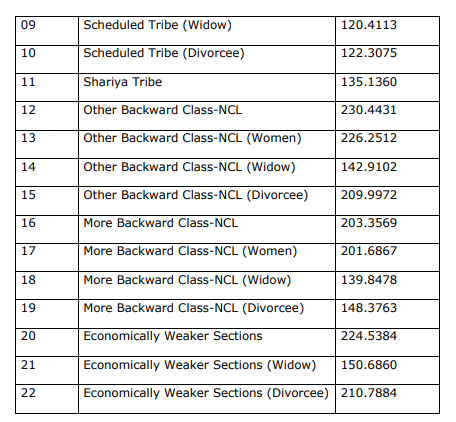

8. Significantly, the cut-off marks for various reserved categories like SC, OBC-NCL, MBC-NCL and EWS were higher than the cut-off marks provided for the General category. The cut-off marks, for various categories, is given hereinbelow:

9. The respondents, belonging to different reserved categories, secured marks in the written test in excess of the cut-off marks for the General category candidates, i.e., 196.3451, but less than the cut-off marks for their respective reserved category. Despite securing marks in excess of the cut-off marks for the General category candidates, the respondents belonging to different reserved categories were treated as aspirants who could compete for the reserved posts only and not the posts which were ‘general’; hence, much to their shock and dismay, they did not figure in the list of successful candidates, eligible to take the typewriting test on computer from their own reserved category in the short-listing process. Relative merit of the reserved category candidates was, thus, given a complete go-bye.

10. As per Note (ii) under Clause 15 of the Advertisement, those candidates who secured minimum 45% marks and 40% marks in the case of SC/ST and persons with benchmark disabilities, respectively, in the written test were eligible for appearing in the typewriting test on computer, subject to a cap of five times the number of vacancies (category wise), but in the same range all those candidates who secured the same percentage of marks were to be included.

11. On 10th May, 2023, one of the respondents, Rajat Yadav, instituted D.B. Civil Writ Petition No. 7564 of 2023 before the High Court. Several other writ petitions were thereafter filed by similarly situated candidates. The prayers in substance were to quash the result dated 1st May, 2023, including the cut-off, and to direct that reserved category candidates who had secured marks greater than the cut-off marks prescribed for the General category be included in the general list and declared qualified for taking the typewriting test.

IMPUGNED ORDER

12. We propose to take note of the impugned order, in some detail, whereby the Division Bench disposed of the writ petitions with suitable directions.

13. It was the contention of the aggrieved writ petitioners4 before the Division Bench that the appellants, being the recruiters, were obliged to shortlist all the candidates – irrespective of the categories to which they belonged, whether in the open category or in any of the reserved categories – to the extent provided in the advertisement, i.e., five times the total number of vacancies and, thereafter shortlist the candidates for typewriting test based on their performance in the written test, and that category-wise shortlisting would be contrary to law.

14. The Division Bench noted that all the vacancies for which the recruitment process was initiated were governed by the provisions with regard to reservation for various categories like ST, SC, OBC (NCL), MBC and EWS, including horizontal reservation for categories like PwD. The Division Bench also noted the permissibility of shortlisting being restricted to the extent of five times the number of vacancies, as provided in the advertisement.

15. It was held by the Division Bench that if the contention of the recruiters, as advanced by learned senior counsel on their behalf were accepted, the object of reservation itself would be jeopardized.

16. Learned senior counsel for the recruiters placed reliance on Chattar Singh and Others v. State of Rajasthan and Others5 where it was held that the rule of migration would not be applicable at the stages of shortlisting of the candidates during screening/preliminary examination as the marks are not added while preparing final merit list and that such migration of reserved category candidates would be applicable only at the time of preparation of the final merit list for the purposes of making appointment. They contended before the Division Bench that if the claim of the petitioning candidates were accepted, the candidates in the OBC category as well as other reserved categories, who obtained higher marks in the written examination were required to be migrated to the open category before the final merit list is prepared, which is impermissible.

17. The Division Bench considered Chattar Singh (supra) wherein Rule 13 of the Rajasthan State and Subordinate Service (Direct Recruitment by Combined Competitive Examination) Rules, 1962 was under challenge. The Rules therein envisaged a two-stage process of Preliminary and Main Examinations which, after an amendment, required declaration of results category-wise. The contention therein that OBC candidates were entitled to the same 5% relaxation in qualifying marks as SC/ST candidates was rejected. It was held therein that such relaxation was confined to SC/ST candidates and that, even prior to the amendment, preparation of category-wise lists was implicit in the scheme of the Rules. In furtherance thereof, the Division Bench rejected the contention that shortlisting of the candidates, categorywise after written examination is contrary to the scheme of the examination. Following this, the Division Bench also rejected the challenge against the provisions contained in the advertisement which provided for category-wise preparation of list by shortlisting the candidates after the written examination.

18. Referring to Dharamveer Tholia and Others v. State of Rajasthan and Another6, the Division Bench noted that it was held therein that a preliminary examination is essentially a screening test to shortlist candidates and that the rider of Article 335 of the Constitution of India cannot be applied at the stage of Preliminary Examination, though, it could be applied to the Main Examination as the Court cannot presume that allowing some candidates to appear in the Main Examination, would automatically lead to their induction in Government service.

19. The Division Bench in the impugned order further noted that in the previous decisions, the common reasoning was that a reserved category candidate could not claim migration to the open category at the stage of the Preliminary Examination, since marks secured therein were not carried forward to the final merit list. It was, however, emphasised that such reasoning had no application once the Main Examination commenced. Distinguishing the precedents, the Division Bench noted that those cases dealt only with claims for migration at the preliminary stage, whereas in the present case, the dispute arose after the written examination forming part of the Main Examination. On this basis, the principles laid down in Dharamveer Tholia (supra) and subsequent decisions of the High Court were held to be inapplicable, and the recruiters’ contentions stood rejected.

20. The Division Bench emphasised that exclusion of a reserved category candidate, despite securing marks higher than the cut-off marks for General/Open category, solely on account of his category, would violate Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution. It was underscored that the placement of a more meritorious reserved category candidate in the Open category is not a facet of reservation, but a principle of equality founded on merit. Relying on Janki Prasad Parimoo v. State of Jammu & Kashmir7, the Division Bench observed that while reservation may involve preferring a less meritorious candidate, it does not require confining a more meritorious reserved category candidate to his own slot, for such confinement would amount to impermissible discrimination.

21. Adverting to the factual position in the batch of petitions before it, the Division Bench noted that the cut-off marks for the General category were lower than those prescribed for SC, OBC (NCL), MBC (NCL), and EWS categories, as can be seen from the table mentioned earlier. On this basis, it was observed that the recruiters, in preparing the lists category-wise, had treated the General/Open category as if it were a compartment reserved exclusively for general candidates. The Division Bench further held that had the lists been prepared purely on the basis of merit across categories, several reserved category candidates would have displaced general category candidates, thereby preserving the constitutional principle of equality.

22. The Division Bench drew support from the Constitution Bench decisions in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India8 and R.K. Sabharwal v. State of Punjab9 to reiterate that a reserved category candidate who secures equal or higher merit cannot be denied equality of treatment merely on account of his caste or community. Any such exclusion, the Division Bench held, would amount to rejecting a more meritorious candidate solely because of the category to which he belongs.

23. In further reinforcement of its views, reliance was placed by the Division Bench on Saurav Yadav v. State of Uttar Pradesh10, wherein it was clarified that reservations, vertical or horizontal, secure representation but are not ‘rigid slots’. The open category is open to all solely on merit, and to confine candidates within quotas would negate merit and amount to communal reservation.

24. Reliance was also placed by the Division bench on U.P. Power Corporation Ltd. v. Nitin Kumar11, wherein the High Court of Allahabad held that reservation earmarks posts for specified categories, but unreserved seats are open to all on merit and not confined to general candidates. It was further held that a reserved category candidate securing selection on open merit cannot be adjusted against reserved vacancies, and that this principle applies throughout the selection process, not merely at the stage of final merit list, since any other view would yield anomalous consequences.

25. In the factual milieu presented before it, the Division Bench noted that the petitioning candidates were unable to find place in the select list of their respective reserved categories, the cut-off marks therein being comparatively high. Nevertheless, their marks were more than what was secured by a substantial number of candidates shortlisted under the general category, yet, they were not treated as open category candidates. The effect of such exclusion amounted to treating the open category as if it were a compartment reserved exclusively for general category candidates, thereby denying entry to more meritorious reserved category candidates. Such an approach, apart from being legally untenable, was held to result in a negation of merit.

26. The petitioning candidates’ contention that the Rules do not permit category-wise shortlisting after the written examination was rejected. On an analysis of the scheme, and relying on Chattar Singh (supra), it was held that preparation of category-wise lists is implicit in the rules. Equally, candidates who had participated in the process with full knowledge of its terms could not later challenge it on being unsuccessful. However, it was clarified that such bar would not extend to questioning whether the settled principle of migration of meritorious reserved category candidates to the open/general category, subject to their not having availed any special benefit, had been adhered to. The objection that the petitioning candidates were estopped from raising this claim was, therefore, rejected. The Division Bench held, as the inescapable conclusion from the foregoing discussion, that while preparing category-wise lists after the written examination, reserved category candidates who had secured marks higher than the cut-off for the general category were required to be included in the open category list. The proper course was first to prepare the General/Open category list strictly on merit, including therein all such reserved category candidates who could compete without availing any special benefit, to the extent of five times the number of vacancies. Only thereafter, the reserved category lists were to be drawn up, excluding those already accommodated in the Open category.

27. It was noted by the Division Bench that some of the petitioning candidates had been permitted to provisionally appear in the typewriting test, while others had not been so fortunate. The Division Bench directed revision of category-wise lists by first preparing the General/Open category list on merit, including therein reserved category candidates who had secured higher marks than the unreserved cut-off, provided they had not availed of any special benefit. The reserved category lists were thereafter to be drawn. Candidates successful in the written test, already permitted to provisionally appear in the typewriting test, were to have their aggregate marks computed – while those not permitted earlier, were to be given an opportunity to appear in a fresh test. The merit lists for both categories were to be re-worked and appointments offered accordingly. It was further directed that if no vacancies remained, less meritorious appointees in either category would have to make way for the more meritorious.

ARGUMENTS OF THE APPELLANT

28. The pivotal contention of Mr. Gupta, learned senior counsel for the appellants, is that non-interference with the impugned order would result in benefits of migration being given twice – first, at the stage of declaration of the results of the written test and the other at the stage of declaration of the typewriting test on computer. According to him, there are authorities in abundance declaring the law on the question of migration and it is now beyond any pale of doubt that the rule of migration of a reserved category candidate (from the category to which he/she belongs) to the general category is attracted at the stage of preparing the final merit list after all tiers of examination have been successfully cleared and not at any intermediate tier of the selection process, i.e., when the exercise of shortlisting of candidates within the respective categories is complete and the marks of all the candidates who have cleared the final tier are available, and the stage is reached for preparing the final merit list. It has been his consistent argument that law, as laid down by this Court and several other high courts, do not permit benefits of migration to be extended to the reserved category candidates at different tiers of the same selection process and such benefit can be availed only once, and that too if the reserved candidate has not availed of any concession/relaxation.

29. Mr. Gupta submitted that several findings recorded by the Division Bench of the High Court in the impugned judgment have not been challenged by the petitioning candidates and, therefore, do not call for any interference by this Court. Two of those findings are as follows and are non-issues before us:

a. The Division Bench held that the preparation of list category wise is implicit in the relevant rules.

b. The Division Bench upheld the restriction of shortlisting to the extent of five times the number of vacancies, as provided in the advertisement.

30. Mr. Gupta next contended that the rule of adjusting a meritorious reserved category candidate in the general category is to be applied at the stage of final selection, i.e., when the final merit list is prepared, and not at the intermediate stage of shortlisting for the second stage of examination. A candidate belonging to a reserved category cannot claim placement in the general category merely on the basis of marks obtained in the written examination, as the written test is only one stage of the selection process. The final determination of merit must await the completion of all stages, including the typewriting test, which carries minimum qualifying marks separately assigned. Hence, the gravamen of his contention is that the rule of migration does not apply at the stage of shortlisting of candidates through screening or preliminary examination but only at the stage of preparation of the final merit or select list for appointment.

31. It was finally urged that having participated in the selection process, the respondents are precluded from challenging the process insofar as the preparation of category-wise list is concerned.

DECISIONS CITED BY MR. GUPTA

32. Mr. Gupta had been called upon by us to cite authoritative decisions of this Court for the proposition he was advancing before us. Multiple authorities on the question of migration have been referred to by Mr. Gupta in his written notes of arguments, which we allowed him to place on record.

33. The decisions cited by Mr. Gupta together with the relevant passages therefrom are noted hereunder:

a. Vikas Sankhala & Ors. v. Vikas Kumar Agarwal & Ors.12 (2 Js): 18. The participants of reserved category candidates in recruitment process of 2012 and 2013 preferred SLP(C) No. 31109 of 2014 wherein this Court issued notice and allowed the appellant Nos. 8 to 13 belonging to 2013 recruitment, to file SLP. In March, 2015, result declared with regard to recruitment of 2013 giving relaxation in accordance with State policy dated March 23, 2011. However, appointments are not given to reserved category candidates availing relaxation although seats have been kept vacant. Moreover, migration to general seats was not allowed. The appellant in SLP(C) No. 31109 of 2014 belonging to 2013 recruitment moved I.A. No. 14 of 2015 seeking direction to the State to prepare merit list of 2013 recruitment in the same manner as done in 2012 recruitment giving benefit of relaxation and migration.

***

24. It so happened that many candidates who belonged to reserved category got higher marks than the last candidates from the general category who was selected for the appointment in the said recruitment process. In terms of its various circulars, which we shall refer to at the appropriate stage, such reserved category candidates who emerged more meritorious than the general category candidates were allowed to migrate in general category. Effect thereof was that these candidates though belonging to reserved category occupied the post meant for general category. According to the writ petitioners (respondents herein), it was impermissible as these reserved category candidates got selected after availing certain concessions and, therefore, there was no reason to allow them to shift to general category. The High Court has accepted this plea treating the relaxation in pass marks in TET as concession availed by the reserved category candidates in the selection process. ***

36. On the aforesaid basis, migration of such reserved category candidates, though emerged as more meritorious in the selection process than the last candidate selected in the general category, are not permitted to migrate to the general category.

***

38.3 (iii) Whether reserved category candidates, who secured better than general category candidates in recruitment examination, can be denied migration to general seats on the basis that they had availed relaxation in TET?

***

78. … It was further pointed out that during the pendency of the matter before this Court, appointments were made by the respective local bodies with respect to recruitment of 2012 giving relaxation in accordance with the State policy dated March 23, 2011 and also allowing migration as per policy dated May 11, 2011 subject to the decision of this Court. The participants of reserved category candidates in recruitment process of 2012 and 2013 preferred SLP (C) No. 31109 of 2014 wherein this Court issued notice and allowed the appellant Nos. 8 to 13 belonging to 2013 recruitment to file SLP. In March, 2015, result declared with regard to recruitment of 2013 giving relaxation in accordance with State policy dated March 23, 2011. However, appointments are not given to reserved category candidates availing relaxation although seats have been kept vacant. Moreover, migration to general seats was not allowed. The appellants in SLP (C) No. 31109 of 2014 belonging to 2013 recruitment, moved I.A. No. 14 of 2015 seeking direction to the State to prepare merit list of 2013 recruitment in the same manner as done in 2012 recruitment giving benefit of relaxation and migration.

***

84.2 Migration from reserved category to general category shall be admissible to those reserved category candidates who secured more marks obtained by the last unreserved category candidates who are selected, subject to the condition that such reserved category candidates did not avail any other special concession. It is clarified that concession of passing marks in TET would not be treated as concession falling in the aforesaid category.

b. Pradeep Singh Dehal v. State of H.P.13 (2 Js)

From Pradeep Singh Dehal (supra), paragraph 15 was referred to us which in turn referenced paragraph 84.2 of the decision in Vikas Sankhala (supra), reproduced supra. It reads:

15. In the judgment reported as Vikas Sankhala v. Vikas Kumar Agarwal one of the questions examined was whether reserved category candidate who obtains more marks than the last general category candidate is to be treated as general category candidate. It was held that such reserved category candidate has to be treated as unreserved category candidate provided such candidate did not avail any other special concession. …

c. Gaurav Pradhan v. State of Rajasthan13: (2 Js)

14. As per Rule 7(1), orders were issued by the State of Rajasthan from time to time providing for reservations and matters connecting therewith. In the present case we are only concerned with the question of migration of reserved category candidate into general/open category candidate. Hence, it is sufficient to note the relevant orders issued by the Government in the above context. The 1989 Rules do not contain any provision regarding migration of reserved category candidates into general/open category candidates, but the government orders which were referable to Rule 7(1) do provide the criteria and basis for such migration. The Circular dated 24-6-2008 was the last circular on the subject prior to initiation of recruitment process. Para 6.2 of the Circular dated 24-6-2008 which has also been extracted by the Division Bench [Rajesh Singh v. State of Rajasthan, 2014 SCC OnLine Raj 6470: (2014) 2 RLW 1585] of the High Court is to the following effect: (Rajesh Singh case [Rajesh Singh v. State of Rajasthan, 2014 SCC OnLine Raj 6470: (2014) 2 RLW 1585], SCC OnLine Raj para 40)

‘Circular dated 24-6-2008

6.2. In the State, members of the SC/ST/OBC can compete against non-reserved vacancies and be counted against them, in case they have not taken any concession (like that of age, etc.) available to them other than that relating to payment of examination fee in case of direct recruitment.’

23. The reservation being the enabling provision, the manner and extent to which reservation is provided has to be spelled from the orders issued by the Government from time to time. In the present case, there is no issue pertaining to the extent of reservation provided by the State Government to the SC, ST and OBC candidates. The issue involved in the present case is as to whether the reserved category candidates can be allowed to be migrated into general category candidates. The reservation is wide enough to include exemption, concession, etc. The exemption, concession, etc. are allowable to the reserved category candidates to effectuate and to give effect to the object behind Article 16 clause (4) of the Constitution. The State is fully empowered to lay down the criteria for grant of exemption, concession and reservation and the manner and methodology to effectuate such reservation. The migration of reserved candidates into general category candidates is also part and parcel of larger concept of reservation and the Government Orders issued on 17-6-1996, 4-3-2002 and 24-6-2008 were the Government Orders providing for methodology for migration of reserved category candidates into general category candidates which was well within the power of State. Neither before us nor even before the High Court, the aforesaid government orders, last being 24-6-2008, were under challenge. As noted above, the High Court itself has returned a finding that earlier methodology of providing for migration of reserved category candidates into general category candidates was reversed by order dated 11-5-2011 by which despite taking any special concession, reserved category candidates could be migrated into general category candidates.

d. Saurav Yadav v. State of U.P.15 (Para 53) (3 Js)

53. The controversy that arises in the present round of litigation is the correct method of filling the quota reserved for women candidates (‘horizontal quota’). It is the complaint of the applicants, who are largely women, belonging to the Other Backward Class categories, that the State has not correctly applied the rule of reservation, and denied such OBC women candidates the benefit of ‘migration’ i.e. adjustment in the General category vacancies.

e. Nirav Kumar Dilipbhai Makwana v. Gujrat Public Service Commission16: (2 Js)

2. The question for consideration in this appeal is whether a candidate who has availed of an age relaxation in a selection process as a result of belonging to a reserved category, can thereafter seek to be accommodated in/or migrated to the general category seat?

***

19. It is evident from the above two circulars that a candidate who has availed of age relaxation in the selection process as a result of belonging to a reserved category cannot, thereafter, seek to be accommodated in or migrated to the general category seats.

***

24. Article 16(4) of the Constitution is an enabling provision empowering the State to make any provision or reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens which in the opinion of the State is not adequately represented in the service under the State. It is purely a matter of discretion of the State Government to formulate a policy for concession, exemption, preference or relaxation either conditionally or unconditionally in favour of the backward classes of citizens. The reservation being the enabling provision, the manner and the extent to which reservation is provided has to be spelled out from the orders issued by the Government from time to time.

***

36. There is also no merit in the submission of the learned counsel for the appellant that relaxation in age at the initial qualifying stage would not fall foul of the circulars dated 29.01.2000 and 23.07.2004. The distinction sought to be drawn between the preliminary and final examination is totally misconceived. It is evident from the advertisement that a person who avails of an age relaxation at the initial stage will necessarily avail of the same relaxation even at the final stage. We are of the view that the age relaxation granted to the candidates belonging to SC/ST and SEBC category in the instant case is an incident of reservation under Article 16(4) of the Constitution of India.

f. Govt. of NCT Delhi v. Pradeep Kumar14: (3 Js)

21. At this stage we need to discuss the Vikas Sankhala judgment in some detail as the High Court and the Tribunal granted relief to the respondents on the basis of this Judgment. The recruitment in Vikas Sankhala, related to Rajasthan where the candidates who availed concession in the CTET examination, were allowed to migrate to Unreserved (or general) category vacancies, if they were more meritorious than the general category candidates.”

29. From the above extract of the two OMs, it is quite apparent that, unlike in Vikas Sankhala, there is an express bar on migration to the unreserved category of those reserved category candidates who had availed of relaxation including those for qualification. …

***

30. The other distinguishing aspect in Vikas Sankhala (supra) is that the candidates who had applied under the reserved category belonged to Rajasthan. For the selection and aspirants from the same State i.e., Rajasthan, the Court allowed such candidates to migrate to the unreserved category.

***

32. The respondents with their CTET qualification under relaxed norms would be eligible for OBC category posts provided their OBC status is certified and recognized by the Delhi government. But such not being the case, they are ineligible for the reserved category vacancies. To allow them to migrate and compete for the open category vacancies would not be permissible simply because, they have secured the CTET qualification with relaxation of pass marks meant for those belonging to the OBC category. As the respondents have not secured the normal pass marks for general category, their eligibility for the general category vacancies is not secured. Therefore, their performance in the selection examination would be of no relevance, in the present process.

g. Sadhana Singh Dangi v. Pinki Asati15: (3 Js) 6.1. Going by the settled principles of law, migration of reserved category candidate on the basis of merit for allotment of a seat in General Category would certainly be applicable to vertical reservation.

h. Ramnaresh @ Rinku Kushwah v. State of Madhya Pradesh16: (2 Js)

16. In view of the settled position of law as laid down by this Court in the case of Saurav Yadav (supra) and reiterated in the case of Sadhana Singh Dangi (supra), the methodology adopted by the respondents in compartmentalizing the different categories in the horizontal reservation and restricting the migration of the meritorious reserved category candidates to the unreserved seats is totally unsustainable. In view of the law laid down by this Court, the meritorious candidates belonging to SC/ST/OBC, who on their own merit, were entitled to be selected against the UR-GS quota, have been denied the seats against the open seats in the GS quota. i. Alok Kumar Pandit v. State of Assam20: (2 Js) 7. The learned counsel for the appellant referred to the provisions of the Assam Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Reservation of Vacancies in Services and Posts) Act, 1978, Assam Public Service Combined Competitive Examination Rules, 1989 and Office Memo No. ARP-338/83/14 dated Dispur, 4-1-1984 issued by the State Government and argued that the reserved category candidates, who were more meritorious than open category candidates, but were appointed against the reserved category posts should be deemed to have been appointed against the posts earmarked for the open category and they cannot be treated as appointed against the posts earmarked for the reserved category, which is constitutionally and legally impermissible. He submitted that if migration is allowed to more meritorious candidates of the reserved category, who, as per their overall merit should be appointed against the general category posts then the quota earmarked for reserved category will be reduced and that would be clearly contrary to the provisions of the Rules framed under the proviso to Article 309 of the Constitution, the reservation policy framed by the State Government and Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution.

ARGUMENTS OF THE PETITIONING CANDIDATES

34. Dr. Chauhan, learned senior counsel for the petitioning candidates, contended that the recruitment process initiated pursuant to the advertisement dated 05th August, 2022 suffered from a fundamental illegality, inasmuch as the General/Open category was treated as an exclusive compartment reserved for non-reserved candidates. Such an approach, it was urged, has the effect of converting the selection into a form of communal reservation, a concept expressly proscribed by the constitutional scheme.

35. Drawing our attention to the decision of this Court in Saurav Yadav (supra), Dr. Chauhan placed particular reliance on the opinion of Hon’ble S. Ravindra Bhat, J. (as His Lordship then was) where it was emphasised that the open category is not a quota, but remains accessible to all candidates irrespective of social classification.

36. It was also urged that the illegality in the present selection process is manifest from the cut-off marks for several reserved categories being demonstrably higher than the cut-off marks for the General/Open category, revealing an impermissible methodology of category-wise segregation at the stage of shortlisting after the written examination.

37. Pointing out that a candidate (who had not availed of any special or additional benefit of reservation) was entitled to be placed in the General/Open category having secured marks well above the cut-off marks for the General/Open category and that denial of such placement resulted in his wrongful exclusion from the next stage of the selection process, namely, the type-writing test on computer, Dr. Chauhan contended that the exclusion of meritorious reserved category candidates at the shortlisting stage itself defeats the very principle of equality based on merit and renders the subsequent stages of selection constitutionally infirm.

38. It was further submitted that the Division Bench in the impugned order correctly applied the settled constitutional principle that a candidate belonging to a reserved category, who secures marks higher than the cut-off prescribed for the General/Open category, is entitled to be considered against the General/Open category.

39. Highlighting that the Division Bench’s directions merely mandate a lawful reworking of the merit lists – by first preparing the Open/General category list strictly on the basis of merit, followed by the preparation of the respective reserved category lists and by granting an opportunity to candidates who were wrongly excluded to participate in the type-writing test, it was next contended that the Division Bench did not confer any undue or preferential advantage on the petitioning candidates, but merely restored them the position they would have occupied had the selection process been conducted in accordance with constitutional norms from its inception.

40. Finally, it was argued that migration of reserved category candidates to the Open/General category cannot be confined only to the final stage of appointment, but must necessarily operate at every stage where merit is assessed and shortlisting is undertaken; otherwise, the primacy of merit, which underlies Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution, would stand diluted by procedural stratification.

OUR OBSERVATIONS, ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

A. PRINCIPLE OF ESTOPPEL

41. Our examination of the erudite arguments advanced by Mr. Gupta must begin with consideration of the objection to the conduct of the petitioning candidates based on applicability of the principle of ‘estoppel’.

42. There is a long line of decisions of this Court that candidates who participated in a selection process cannot later challenge the procedure adopted merely because the result is not palatable to them. It has been held there, generally, that the principle of estoppel operates against such a candidate who, having taken a calculated chance of selection by participating in the selection process and failed to secure selection, challenges the process of selection in Court on the ground of a flawed procedure being adopted by the recruiting/selecting authority. Profitable reference may be made to some of the decisions of this Court, viz. G. Sarana v. University of Lucknow17, Om Prakash Shukla v. Akhilesh Kumar Shukla18, Madan Lal v. State of Jammu & Kashmir19, K.A. Nagamani v. Indian Airlines20, Manish Kumar Shahi v. State of Bihar21, Ramesh Chandra Shah v. Anil Joshi22 and Ramjit Singh Kardam v. Sanjeev Kumar23.

43. However, this rule is not absolute. As elucidated in Meeta Sahai v. State of Bihar24, participation of a candidate in a selection process implies acceptance of the prescribed procedure, but not of any illegality in the conduct of the said procedure or constitutional infirmity underlying it. Where the challenge pertains to a misconstruction of statutory rules or violation of constitutional principles, the plea of estoppel cannot operate as a bar.

44. This distinction was earlier recognised by a Bench of three Judges in Raj Kumar v. Shakti Raj25, where despite participation, the Court held that glaring illegalities in the process rendered estoppel inapplicable.

45. Having considered the precedents in the field, to our mind, a candidate would be estopped from challenging a selection process postparticipation, unless he can show that despite due diligence, he could not have known earlier of the illegality in the procedure that came to be adopted or that the procedural flaw striking at the root of the selection process was hidden and surfaced only after completion of the process of selection; hence, no challenge could have been laid by him prior to his participation in the process.

46. In the present case, the advertisement was a representation to the aspirants for public employment that category-wise lists would be prepared. None would question such a condition. There was, however, no indication that meritorious reserved category candidates would not be treated as General/Open category candidates even if they outscore the latter. The illegality lies in the action of the appellants in not treating the meritorious reserved category candidates as General/Open category candidates, despite noticing that the former had outperformed and outshone the latter. Since the petitioning candidates could not have possibly visualised such an approach on the part of the recruiters by projecting their own imagination and discover all facts and circumstances that might be in their contemplation to be adopted while drawing up the merit lists at the time they participated in the preliminary written examination, the question of such candidates being estopped from mounting a challenge to the legality of the process does not and cannot arise. The petitioning candidates paid a price for their merit and having challenged the very legality of the process alleging violation of constitutional norms and legal principles, the plea of estoppel could not have defeated such a challenge.

47. The Division Bench by entertaining the writ petitions and granting relief of the nature noticed above cannot be held to have exercised jurisdiction illegally.

B. ON ‘DOUBLE BENEFIT’

48. Moving on with consideration of the objection regarding ‘double benefit’, we see no reason to agree.

49. A reserved category candidate, howsoever meritorious he/she might be, in present times has to face stiff competition from other equally meritorious candidates having regard to dearth of jobs in our country. It is out of an anxiety to obtain an employment that such a reserved category candidate typically indicates the category to which he/she belongs for being considered for appointment on a reserved vacancy. Certainly, mere indication of one’s reserved category in the application form does not automatically qualify the candidate for appointment on a reserved vacant post but only enables him/her to stake a claim amongst all reserved candidates based on the inter se merit position. Equally, for a deserving reserved category candidate to be appointed on an unreserved vacant post, it is merit and merit alone that must determine suitability. In other words, for the unreserved vacant posts, the inter se merit among all the competing candidates serves as the benchmark for appointment in public service.

50. Bearing such well-acknowledged legal position in mind, we have no hesitation to record our clear agreement with the view expressed by the Division Bench, notwithstanding the assiduous arguments of Mr. Gupta. The premise underlying the argument of potentially conferring ‘double benefit’ to the candidates of the reserved category proceeds on an erroneous assumption that a reserved category candidate is necessarily availing the benefit of reservation at more than one/every stage of a multi-tier process. It is entirely conceivable that a candidate belonging to a reserved category may, on his or her own merit, secure marks in the preliminary stage exceeding the cut-off for the unreserved category and may, likewise, on cumulative assessment, surpass the unreserved cut-off in the final stage as well. In such a situation, the reserved candidate does not draw upon the benefit of reservation at any stage and is entitled to be considered and appointed against an unreserved vacant post purely on merit. The apprehension of a ‘double benefit’, therefore, is misconceived, since the availability of reservation does not operate as a bar for a reserved category candidate from being considered on merit against the unreserved category, placement therein depending solely on merit demonstrably sufficient at the particular stage, a proposition we propose to examine.

C. PRECEDENTS ON ‘MIGRATION’

51. Having read the extracts of the precedents referred to us by Mr. Gupta on the question of migration, we have not found the same to support the proposition of law he has argued. However, before inching ahead, for the sake of completeness, we wish to advert to certain omitted paragraphs from the precedents that were cited as well as a couple of more precedents bearing on the issue for presenting a holistic and coherent picture of the legal position governing migration of reserved category candidates in a multi-tier selection process.

52. Paragraph 15 of Pradeep Singh Dehal (supra) was referred to by Mr. Gupta. However, we wish to refer to paragraphs 16 and 17 of the said decision as well for a complete perspective on the reasoning of this Court. The same are reproduced below:

16. The concessions which were availed by the reserved category candidates are in the nature of age relaxation, lower qualifying marks, concessional application money than the general category candidates.

17. In view of the said fact, we find that the selection process conducted by the University cannot be said to be fair and reasonable. Consequently, the University is directed to re-examine the selection process by constituting an Expert Committee who shall consider the “publications” of the candidates who were being considered in pursuance of Advertisement No. 3 of 2011 and make suitable recommendations accordingly by having a joint merit list of all the categories of candidates who applied for appointment to the post of Assistant Professor. However, in such selection process, the appointment of candidates already selected will not be disturbed, except the appellant whose appointment shall be subject to the decision of the University on the basis of recommendation of the Expert Committee.

53. Paragraph 7 of the decision in Alok Kumar Pandit (supra) was referred. For completeness, the relevant extracts from the said decision containing the answer to the question noticed in paragraph 7 are reproduced below:

13. If the proposition laid down in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India [1992 Supp (3) SCC 217 : 1992 SCC (L&S) Supp 1 : (1992) 22 ATC 385] and R.K. Sabharwal v. State of Punjab [(1995) 2 SCC 745 : 1995 SCC (L&S) 548 : (1995) 29 ATC 481] are considered in abstract, it may be possible to say that once a reserved category candidate secures higher merit than open category candidates, he can be considered for appointment only against open category post and the quota of the particular reserved category cannot be reduced by treating his appointment as one made against the post earmarked for the reserved category to which he belongs. However, literal application of this proposition can lead to serious anomaly and discrimination inasmuch as more meritorious candidate of the particular reserved category could be deprived of the service/cadre/post of his choice/preference and less meritorious candidate of the reserved category could get appointment on the post which would otherwise be available to more meritorious candidate. This can be illustrated by the following example: X and Y are members of reserved category. They compete for selection for recruitment to All-India Services, which includes, IAS, IPS, IRS, etc. In the merit list prepared by the Commission X is placed higher than some of the open category candidates but on the basis of his overall inter se merit with the open category candidates he could get appointment only to IRS. X can get the post of his choice/preference i.e. IAS provided his case is considered for appointment against the posts earmarked for the particular reserved category to which he belongs. If he is not allowed to do so, then why (sic., Y) who is less meritorious than X within the reserved category will get appointment to IAS against the reserved post. In this manner X will, despite his better merit within the reserved category, stand discriminated in the matter of appointment against the post for which he had given his preference.

***

24.1. A reserved category candidate who is adjudged more meritorious than the open category candidates is entitled to choose the particular service/cadre/post as per his choice/preference and he cannot be compelled to accept appointment to an inferior post leaving the more important service/cadre/post in the reserved category for less meritorious candidate of that category.

54. In Jitendra Kumar Singh v. State of U.P.26, this Court [while construing the Uttar Pradesh Public Services (Reservation for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes) Act, 1994 and the executive instructions issued thereunder] drew a clear distinction between concessions granted at the threshold stage such as reduced fee and age relaxation (to enable participation in the selection process) and relaxation in the standards of selection. The relevant paragraphs therefrom read as follows:

72. Soon after the enforcement of the 1994 Act the Government issued Instructions dated 25-3-1994 on the subject of reservation for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and other backward groups in the Uttar Pradesh Public Services. These instructions, inter alia, provide as under:

“4. If any person belonging to reserved categories is selected on the basis of merits in open competition along with general category candidates, then he will not be adjusted towards reserved category, that is, he shall be deemed to have been adjusted against the unreserved vacancies. It shall be immaterial that he has availed any facility or relaxation (like relaxation in age-limit) available to reserved category.”

From the above it becomes quite apparent that the relaxation in agelimit is merely to enable the reserved category candidate to compete with the general category candidate, all other things being equal. The State has not treated the relaxation in age and fee as relaxation in the standard for selection, based on the merit of the candidate in the selection test i.e. main written test followed by interview. Therefore, such relaxations cannot deprive a reserved category candidate of the right to be considered as a general category candidate on the basis of merit in the competitive examination. Sub-section (2) of Section 8 further provides that government orders in force on the commencement of the Act in respect of the concessions and relaxations including relaxation in upper age-limit which are not inconsistent with the Act continue to be applicable till they are modified or revoked.

***

75. In our opinion, the relaxation in age does not in any manner upset the “level playing field”. It is not possible to accept the submission of the learned counsel for the appellants that relaxation in age or the concession in fee would in any manner be infringement of Article 16(1) of the Constitution of India. These concessions are provisions pertaining to the eligibility of a candidate to appear in the competitive examination. At the time when the concessions are availed, the open competition has not commenced. It commences when all the candidates who fulfil the eligibility conditions, namely, qualifications, age, preliminary written test and physical test are permitted to sit in the main written examination. With age relaxation and the fee concession, the reserved candidates are merely brought within the zone of consideration, so that they can participate in the open competition on merit. Once the candidate participates in the written examination, it is immaterial as to which category, the candidate belongs. All the candidates to be declared eligible had participated in the preliminary test as also in the physical test. It is only thereafter that successful candidates have been permitted to participate in the open competition.

55. More recently, in Deepa E.V. v. Union of India27, this Court elucidated an important qualification to the principle enunciated in Jitendra Kumar Singh (supra). This Court held that should the governing statutory rules or executive instructions provide for an express bar that candidates belonging to the Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe or Other Backward Classes, having availed any relaxation or concession, shall not be adjusted against unreserved vacancies, such express bar would have primacy. The instructive passages from the decision are set out below:

4. The appellant, who has applied under OBC category by availing age relaxation and also attending the interview under the “OBC category” cannot claim right to be appointed under the General category.

***

8. The learned counsel for the appellant mainly relied upon the judgment of this Court in Jitendra Kumar Singh v. State of U.P. [Jitendra Kumar Singh v. State of U.P., (2010) 3 SCC 119 : (2010) 1 SCC (L&S) 772] , which deals with the U.P. Public Services (Reservation for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes) Act, 1994 and Government Order dated 25-3- 1994. On a perusal of the above judgment, we find that there is no express bar in the said U.P. Act for the candidates of SC/ST/OBC being considered for the posts under general category. In such facts and circumstances of the said case, this Court has taken the view that the relaxation granted to the reserved category candidates will operate a level playing field. In the light of the express bar provided under the proceedings dated 1-7-1998 the principle laid down in Jitendra Kumar Singh [Jitendra Kumar Singh v. State of U.P., (2010) 3 SCC 119 : (2010) 1 SCC (L&S) 772] cannot be applied to the case in hand.

56. At this stage, it is necessary to clarify that the present case stands on a different footing from the principles of law discussed above. No such concession or relaxation has been extended to the petitioning candidates and the controversy before us is confined to a narrower question, namely, whether a candidate belonging to a reserved category, who has secured marks higher than the cut-off for the general category in the preliminary/screening stage, is to be treated as having qualified against an open or unreserved vacant post, or whether such candidate must necessarily be confined to the reserved category alone.

D. MIGRATION- MEANING AND APPLICABILITY

57. We are convinced, on the facts that have emerged, that we have an “open” slate before us. As would unfold from the discussion hereafter, our stance remains unchanged from what was conveyed to Mr. Gupta in course of hearing.

58. We begin our observations, analysis and ruling on migration by refreshing our memory with certain well-established principles in relation to affirmative action under our Constitution. It is well-settled that the concept of ‘equality before law’ ingrained in Article 14 of the Constitution of India contemplates, inter alia, elimination of inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities not only amongst individuals but also amongst groups of people and is aimed at securing the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the society and to protect them from social injustice and exploitation. The equal protection clause urges affirmative action for those who are placed unequally. Affirmative action is also recognised by Article 16. Then again, Article 335 thereof provides for special consideration in the matter of claims of the Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes for public employment. The entire field of law relating to affirmative action is so well occupied by authoritative decisions that we consider it unnecessary to burden this judgment by referring to the same. What particularly concerns us in these appeals is not a sterile invocation of formal legal equality, but an assessment of the real-world consequences flowing from the principle of equality. The focus, therefore, must be on outcomes as much as on rules.

59. Indra Sawhney (supra) explained the principles of reservation. Hon’ble B.P. Jeevan Reddy, J. (as His Lordship then was) declared, inter alia, that where a vertical reservation is made in favour of a backward class, the candidates in this category may compete for open or general category and that if they are appointed on merit in the open or general category, their number will not be counted against the backward class category and, as such, it cannot be considered that the vertical reservations have been filled up to the extent candidates of this category have migrated to the open category on merit.

60. In Saurav Yadav (supra), Hon’ble S. Ravindra Bhat, J. in His Lordship’s supplementing opinion28 outlined the features of vertical and horizontal reservation as follows: 59. The features of vertical reservations are:

59.1. They cannot be filled by the open category, or categories of candidates other than those specified and have to be filled by candidates of the social category concerned only (SC/ST/OBC).

59.2. Mobility (“migration”) from the reserved (specified category) to the unreserved (open category) slot is possible, based on meritorious performance.

59.3. In case of migration from reserved to open category, the vacancy in the reserved category should be filled by another person from the same specified category, lower in rank.

59.4. If the vacancies cannot be filled by the specified categories due to shortfall of candidates, the vacancies are to be “carried forward” or dealt with appropriately by rules.

60. Horizontal reservations on the other hand, by their nature, are not inviolate pools or carved in stone. They are premised on their overlaps and are “interlocking” reservations49. As a sequel, they are to be calculated concurrently and along with the inviolate “vertical” (or “social”) reservation quotas, by application of the various steps laid out with clarity in para 21.3 of Lalit, J.’s judgment. They cannot be carried forward. The first rule that applies to filling horizontal reservation quotas is one of adjustment i.e. examining whether on merit any of the horizontal categories are adjusted in the merit list in the open category, and then, in the quota for such horizontal category within the particular specified/social reservation.

61. The open category is not a “quota”, but rather available to all women and men alike. …”.

61. The above observations were followed by His Lordship’s observation, found almost at the end of the opinion, that the “open category is open to all, and the only condition for a candidate to be shown in it is merit, regardless of whether reservation benefit of either type is available to her or him.”. The same have a profound meaning, and needs to be translated into action without being unnecessarily bothered by a term like ‘migration’.

62. Drawing inspiration from the guiding light provided by Indra Sawhney (supra) and Saurav Yadav (supra), we hold that the word ‘open’ connotes nothing but ‘open’, meaning thereby that vacant posts which are sought to be filled by earmarking it as ‘open’ do not fall in any category. One does find categories like ‘open’ or ‘unreserved’ or ‘general’ being widely used in course of recruitment drives but they are meant to signify the open/unreserved vacant posts on which any suitable candidate can be appointed, regardless of the caste/tribe/class/gender of such candidate. For all intents and purposes, the vacancies on posts which are notified/advertised as open or unreserved or general, as the terms suggest, are not reserved for any caste/tribe/class/gender and are, thus, open to all notwithstanding that a cross-section of society can also compete for appointment on vacant posts which are ‘reserved’ – vertical or horizontal – as mentioned in the notification/advertisement.

63. Now, turning to the dictionary meaning of the word ‘migration’, what we find is that the same typically refers to the act of moving from one place to another, often involving a change of residence or location. This can apply to various contexts like human migration, animal migration, data migration, etc. In general, migration involves a change of location, often with the intention of settling or establishing a new presence in the new location.

64. In the context of reservation in public employment, the word ‘migration’ refers to a candidate claiming benefits or entitlements. The word is used in, at least, two scenarios.

65. Scenario 1 is “Inter-State Reservation Migration” envisaging a portability of reservation benefits. Since we are not concerned with a scenario 1 case, we make no observation except noting two decisions of this Court. The first is Action Committee v. Union of India29 where it has been held by a Constitution Bench that a person belonging to Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe in relation to his original State, of which he is a permanent or ordinary resident, cannot be deemed to be so in relation to any other State on his migration to that State for the purpose of employment, education, etc. The second is Uttar Pradesh Public Service Commission v. Sanjay Kumar Singh30 holding that if a person certified as Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe in one State migrates to another State, then he would not be entitled to the benefit available to Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe in the State to which he has migrated unless he belongs to the Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe in that State.

66. Scenario 2, with which we are concerned, occurs when there is a “Merit Induced Shift”. Although this shift is largely referred to as migration, we find in Saurav Yadav (supra) Hon’ble Ravindra Bhat, J. explaining the term as adjustment of a reserve category candidate in the unreserved category based on his/her merit.

67. Here, we do not see reason to agree with Mr. Gupta that any shift or adjustment, or even migration as he contends, as such is required where a candidate, who is also otherwise entitled to compete and be selected for a reserved vacant post, happens to outscore, outperform and outshine not only reserved candidates but also general candidates and figures at the top of the list of successful candidates prepared after a qualifying/preliminary examination (for screening/shortlisting) solely by dint of the marks secured by him/her in such examination (without availing any concession/relaxation) thereby entitling him/her to participate in the second tier of a further suitability test. Such a meritorious candidate, notwithstanding that he/she belongs to a reserved category, be it Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe or Other Backward Class, must of necessity (arising out of the concept of equality before law and equal protection of the laws in Article 14, and extended to Article 16 in matters of public employment) be treated as a candidate who has competed for the ‘unreserved’ category and not the ‘reserved’ category, thereby obviating the need for any ‘migration’ or, so to say, shift or adjustment.

68. In a two-tier process, as in the present case, we wish to illustrate how, generally, the exercise of screening/short-listing of candidates (belonging to General/Open, Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe or Other Backward Class, etc., categories) with five times the number of vacancies in each category, who would literally be gaining the ‘pass’ to reach the second tier to participate in the typewriting test on computer can be conducted without complaints of unfairness and nontransparency in the process. Say, 100 vacancies in the General/Open category are notified and a similar number for the reserved categories is also notified. Five times the number of vacancies would mean not more than 500 candidates can be screened/shortlisted for the General/Open category. At the outset, based on the performance of the candidates who take the written test, the recruiting authority has to screen/short-list the candidates to be included in the General/Open category and subsequently for reserved categories. Judicial notice can be taken that this exercise is often facilitated by preparing a broadsheet, also called a short-list, containing names of all the candidates (who acquit themselves successfully in the written test). For the preparation of the short-list for the General/Open category, candidates are first arranged strictly in descending order of merit and, thereafter, candidates falling short of the cut-off for such category figure in descending order of merit according to their respective reservation category in separate short-lists. If any candidate, say ‘C’, being the member of a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe or Other Backward Class, outscores the candidates not belonging to any reserved category in the written test, he/she shall be included in the short-list for the General/Open category. At this stage, there is no question of any migration; merit is the only criterion amongst all candidates who have to be seen as belonging to General/Open category. Once ‘C’ gains the ‘pass’ for the second-tier process and qualifies in the typewriting test on computer obtaining marks in excess of the requisite marks, his/her marks obtained in such test would be required to be added to the marks obtained in the written test. Once again, a broad-sheet has to be prepared based on cumulative scores containing names of all the candidates in order of highest to lowest marks with the more meritorious candidates, obviously, figuring at the top. Preparation of this broad-sheet is a handy tool for drawing up the final merit list of candidates. From the broad-sheet, names of candidates drawn up in order of merit with candidates ranked according to their marks in descending order, commonly called the Combined Merit List, ought to reflect where each one of the aspiring candidates stand on merit. If ‘C’ figures within the first 100 candidates in order of merit, i.e., the number of vacant posts for the General/Open category, he/she shall be counted as a General/Open candidate for the purpose of appointment. Here too, there is no question of migration for the reason we have already indicated above, i.e., merit being the only criterion and not caste/tribe/gender, etc. If ‘C’ does not figure in the first 100 candidates and whilst preparing the merit list of reserved category candidates it is found that he/she figures within the specified number of vacancies in the reserved category to which he/she belongs and which can be filled up by appointing him/her, he/she ought to be counted as a candidate of such reserved category for appointment. If ‘C’ fails to figure in the merit list for the reserved category list as well, question of his/her appointment would not arise.

69. We, however, sound a note of caution that our observations above are relatable to the selection process of the kind under consideration. It has not been shown with reference to the recruitment rules that the same ordains otherwise. If, at all, the recruitment rules governing any selection process ordain otherwise than what is observed above, obviously the recruitment rules would have precedence subject to the condition that such rule passes the test of constitutionality.

70. Reverting to the appeals under consideration, we see no reason to say that there has been a ‘migration’, in the sense of either an adjustment or a shift being made. At the time of screening/short-listing of candidates based on their performance in the qualifying examination and even thereafter, initially all the aspiring candidates including the reserved candidates should be seen as General/Open candidates. If such a candidate, notwithstanding that he/she belongs to a reserved category maintains excellence in standard even in the second tier of examination (typewriting test, in this case), he/she would cease to be treated as a candidate belonging to any category and entitled to treatment as a candidate seeking appointment on a vacant post which is categorised as General/Open. Should there be a decline in performance in the second tier test pushing out the candidate from the zone of consideration for appointment on posts which are open or unreserved or general but not beyond the zone for the reserved vacant posts, it is necessary to regard him/her as a candidate belonging to the reserved category to which he/she belongs, thereby paving the way for him/her to stake a claim for consideration for appointment on an appropriate reserved vacant post.

71. In the milieu of facts, none of the petitioning candidates has been shown to have availed of any concession/relaxation. No law – either rule or executive instruction – has been shown which prevented the High Court from treating the reserved candidates as General/Open candidates once it transpired that they outshone the latter. Question of any migration or deriving twin benefits of migration did not and could not arise in the circumstances.

72. If we accept the proposition advanced by the appellants, it would not only have a detrimental impact on candidates from the disadvantaged sections but also erode the principles enshrined in the Constitution.

73. Now, turning to Chattar Singh (supra) which was heavily relied on by the appellants, we have to record that the ratio laid down therein must be appreciated in its proper context. In that case, the scheme of examination clearly provided that the marks obtained in the preliminary examination would not be considered for the determination of final merit. The rule therein, appearing from paragraph 5 of the decision, read as follows:

5. Rule 13 of the Rules prescribes the mode of conducting preliminary as well as Main Examination. It reads as under:

“13. Scheme of Examination, personality and viva voce test.— The competitive examination shall be conducted by the Commission in two stages, i.e., Preliminary Examination and Main Examination as per the scheme specified in Schedule III.

The marks obtained in the Preliminary Examination by the candidates, who are declared qualified for admission to the Main Examination will not be counted for determining their final order of merit…”

(emphasis ours)

It is in view of this rule that this Court held that the claim of reserved category candidates to be accommodated in the open category on the basis of marks obtained will be determined at the final stage. We find no reason to differ from that principle. However, the facts of the present case stand on a distinct footing. First, the main written examination here is not a mere preliminary/screening test but an integral and substantive component of the selection process, carrying 300 marks out of a total of 400 – constituting 75% of the final assessment. Its weight and determinative value distinguish it from the limited preliminary stage examination contemplated in Chattar Singh (supra), thereby rendering that ratio inapplicable to the present factual matrix. Secondly, the inclusion of a reserved category candidate in the open merit list at the stage of shortlisting cannot be equated with ‘migration’, for no benefit or concession of reservation is availed. Such inclusion is purely merit-based and, therefore, stands on a plane distinct from the concept of ‘migration’ as addressed in Chattar Singh (supra).

74. Before we part, we find it necessary to enter a caveat. A situation could arise, if the aforesaid principles were applied, of a reserved category candidate based on his/her performance outshining General/Open candidates and figuring in the General merit list, but finding the options to be limited. He/she may, as a consequence of being counted as a General candidate, lose out on a preferred service or a preferred post because the same is reserved for a reserved category candidate. Should such an eventuality occur, the same is bound to breed dissatisfaction, disappointment and displeasure which are not in the interests of public service. After all, fairness matters even in public employment. Where adjustment against the unreserved category would result in a more meritorious reserved category candidate being displaced in favour of a less meritorious candidate within the same category for a preferred service or a preferred post within the reserved quota, the former must be permitted to be considered against the service/post in the reserved quota. This would ensure merit being preserved both across categories and within them, and that reservation functions as a means of inclusion rather than an instrument of disadvantage. The approach adopted by us in holding so is consistent with the view expressed by this Court, encapsulated in paragraph 24.1 of Alok Kumar Pandit (supra). We may also mention here that prior to the view expressed in Alok Kumar Pandit (supra), the High Court at Calcutta in a somewhat like situation took the same view in Mukul Biswas v. State of West Bengal31.

75. We appreciate the proactive stance of the Division Bench of the High Court while it rectified a situation where the High Court itself was found to contravene constitutional ideals.

CONCLUSION

76. For the foregoing reasons, the impugned order is upheld. As a sequel thereto, the appeals fail and are dismissed.

77. While considering the cases of the petitioning candidates, the High Court may endeavour not to dislodge employees in position, as expressed by the Division Bench, as far as possible.

78. Parties shall, however, bear their own costs.

79. Time to comply with the impugned order is extended by two months from date.

- impugned order [↩]

- appellants [↩]

- Persons with Disabilities [↩]

- petitioning candidates [↩]

- (1996) 11 SCC 742 [↩]

- 2000 (3) WLC 399 [↩]

- AIR 1973 SC 930 [↩]

- 1992 Supp (3) SCC 217 [↩]

- (1995) 2 SCC 745 [↩]

- (2021) 4 SCC 542 [↩]

- 2015 SCC OnLine All 8611 [↩]

- (2017) 1 SCC 350 [↩]

- (2018) 11 SCC 352 [↩]

- (2019) 10 SCC 120 [↩]

- (2022) 12 SCC 401 [↩]

- 2024 SCC OnLine SC 2058 [↩]

- (1976) 3 SCC 585 [↩]

- 1986 Supp SCC 285 [↩]

- (1995) 3 SCC 486 [↩]

- (2009) 5 SCC 515 [↩]

- (2010) 12 SCC 576 [↩]

- (2013) 11 SCC 309 [↩]

- (2020) 20 SC 209 [↩]

- (2019) 20 SCC 17 [↩]

- (1997) 9 SCC 527 [↩]

- (2010) 3 SCC 119 [↩]

- (2017) 12 SCC 680 [↩]

- the Editor’s note in the SCC report suggests that all three Hon’ble Judges on the Bench

had signed the supplementing opinion. [↩] - (1994) 5 SCC 244 [↩]

- (2003) 7 SCC 657 [↩]

- 2010 SCC OnLine Cal 1983 [↩]