Analysis

Making sense of the Supreme Court’s intervention in ED v State of West Bengal

A clash between central investigators and state authorities forces the Court to confront federalism’s breaking points

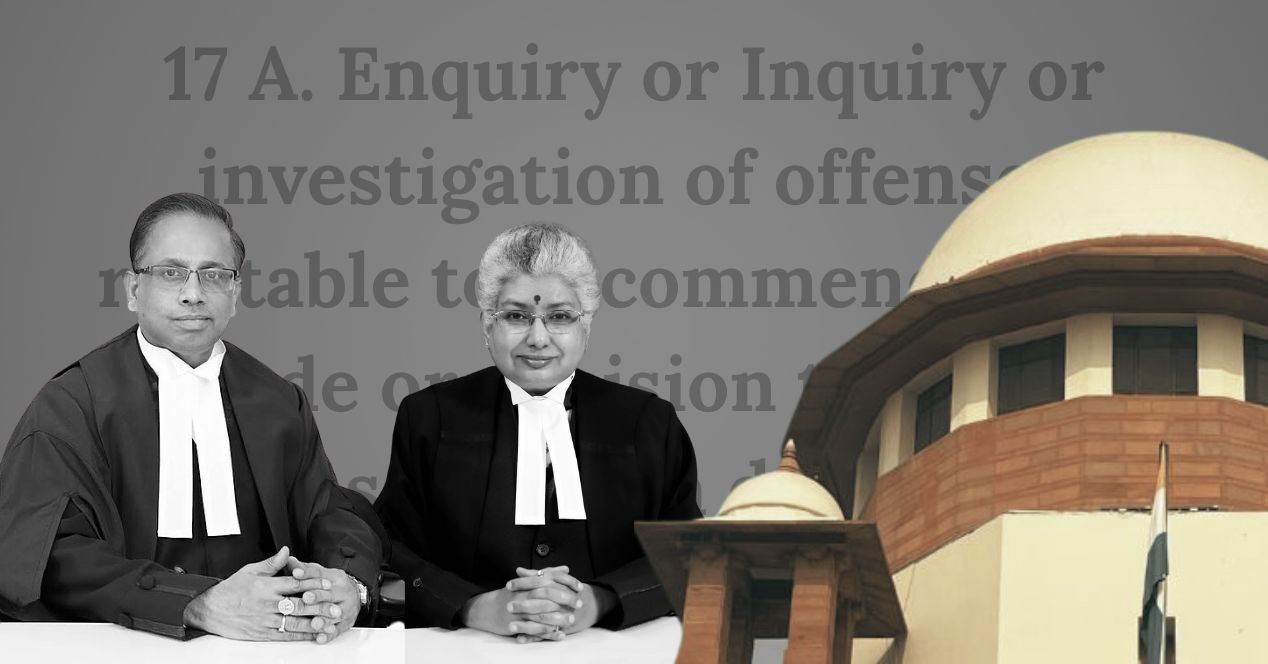

The interim order in Directorate of Enforcement v State of West Bengal by a Division Bench of Justices P.K. Mishra and V.M. Pancholi raises an important constitutional question: how should investigative autonomy be safeguarded in a federal structure where political interests and law enforcement frequently collide?

The case involves a recurring tension between central agencies and the state investigative authorities. The conflict emerged when the Enforcement Directorate (ED) alleged interference and reprisals by State authorities during a money laundering probe in Calcutta. They claim that the West Bengal police and the State Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee visited the premises to interfere with a search operation. The West Bengal police also registered FIRs against the ED officers.

The State leadership has claimed that the central investigative agencies were misused for political advantage. What sets this matter apart is not merely the factual context but the Court’s depiction of the standoff as symptomatic of a broader breakdown in institutional functioning—a drift towards lawlessness if such dynamics persist unchecked.

The immediate flashpoint

The litigation was prompted by a search operation conducted by the ED in connection with an alleged scam involving more than ₹2700 crores at the residence of Pratik Jain of Indian Political Action Committee (I-PAC). The I-PAC is a political consultancy involved in campaign work. Solicitor General Tushar Mehta and Additional Solicitor General S.V. Raju, appearing for the ED, argued that the state authorities, including the Chief Minister, had interfered despite being asked not to intervene. Moreover, materials collected by the ED were taken away, followed by the FIRs against the officers.

They argued that this incident raises concerns about the ability of the central law enforcement to operate independently, without fear of reprisal from politically sensitive actors. The fact that individual ED officers have approached the Court, alongside the agency, suggests that this is not a mere turf war over jurisdiction.

High Court proceedings

The ED implored the Supreme Court to hear the case, pointing out that the proceedings in the Calcutta High Court were disrupted, allegedly by the Trinamool Congress. The record of proceedings in the Calcutta High Court reveals that there was “enormous disturbance and commotion”, for which the hearing was adjourned.

The Supreme Court reproduced the High Court’s observation in its interim order. This signals an alarm over how judicial decorum can erode in politically sensitive cases. It is in this background that the top court agreed to hear the case under Article 32, despite pending proceedings at the High Court. Appearing for one of the respondents, Senior Advocate Shyam Divan had argued that the High Court proceedings may continue, as subsequent hearings in the matter were taken up peacefully. Though the Court does not invoke any explicit exception to the principle of alternate remedies, its reasoning suggests that ordinary institutional channels may be inadequate when allegations involve constitutional functionaries and senior police officials.

Investigative integrity

Paragraphs 16 to 19 in the interim order reflect on the constitutional dimensions of the dispute: a test of whether law enforcement agencies—central and state—can operate independently and impartially.

The Court warns that the political configuration of the state may result in a scenario where agencies entrusted with upholding the law shield “offenders”. This can have consequences on the uniform application of the legal process as it has the potential for fragmented enforcement and selective accountability. At the same time, the Court reiterates that central agencies must not interfere with legitimate political activity, especially during election periods. The unresolved question—whether references to political work can immunise actors from legitimate criminal scrutiny—is left open.

Maintainability and judicial priorities

The State of West Bengal, through senior advocates, Kapil Sibal and Abhishek Singhvi, argued that the ED’s petitions were driven by electoral motives, that they were filed in anticipation of elections and that the High Court was already seized of the matter. These are familiar contentions in cases involving central agencies and opposition-led State governments.

Yet, the Supreme Court’s interim order sidesteps the motive argument for the time being. It focuses instead on the structural implications of the alleged interference, treating it as a threshold issue affecting institutional integrity. This suggests that the Court is inclined to look into questions of investigative frameworks over political motivations, at least at the preliminary stage.

The Court stayed the FIRs lodged against the ED officers and directed that the CCTV footage and digital data from the search site should be preserved. This will temporarily protect the central investigators without halting the broader money-laundering investigation.

The federal dimension

This interim order must be seen in the context of growing constitutional friction in the Indian federal system. The courts have been repeatedly drawn into disputes which blur the line between legal process and political contestation.

What distinguishes this case is the emphasis on coercive retaliation—criminal charges against investigators, alleged disruption of courtrooms and the threat of investigative paralysis. The Court’s invocation of “lawlessness” reflects a structural anxiety about the uneven enforcement of law across different political geographies. When the legitimacy of an investigation becomes dependent on partisan alignment, the foundational promise of the rule of law is placed at risk.

For now, its interim order reaffirms a basic constitutional expectation: that agencies of the State, regardless of their political setting, must function with legal integrity and mutual restraint.

Hearing of the case is likely to resume on 3 February.