Analysis

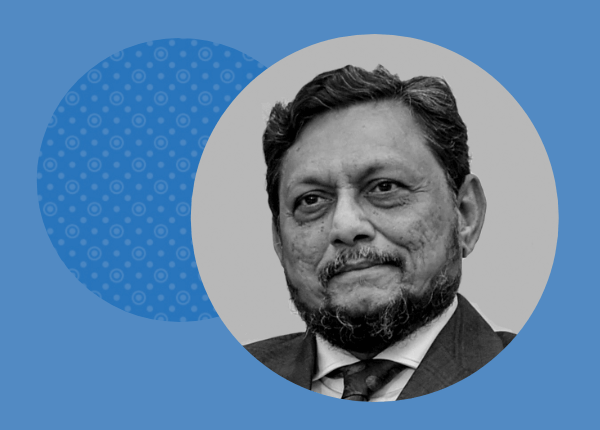

J. Ramana Sworn In as 48th Chief Justice

CJI Ramana's seven-year term as a Supreme Court judge, through numbers and key judgments.

CJI NV Ramana was sworn in as the 48th Chief Justice of India today, on 24 April 2021. In this post, we look back at his seven-year term as a Supreme Court judge, through numbers and key judgments.

Initially working as a journalist, CJI Ramana enrolled as an advocate in 1983. He practiced before the Andhra Pradesh High Court (AP HC), other Courts in the state and the Supreme Court. He was appointed Permanent Judge of the AP HC on 27 June 2000. He was subsequently elevated as the Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court. On 17 February 2014, he was elevated to the Supreme Court.

CJI Ramana will hold his Chief Justiceship until his retirement is due on 26 August 2022. His tenure will be 1.3 years long. This is little below the average tenure of 1.5 years for CJIs.

CJI Ramana Wrote 157 Judgments, Mostly on Criminal Law

Ramana has written 157 judgments to date. This is above the average of 105 judgments by judges currently on the bench. However, he has already been on the bench for close to 7 years. So he has written less than the average of 25.7 judgments a year, at 22.43 a year.

Of these, a majority (51%) dealt with the criminal law. Other areas he has written more judgments in include property law and motor vehicles cases.

He has been on the bench for 574 cases in which a judgment was pronounced. This means he has written a judgment in 27.35% of his cases. 2018 was his most active year.

Key Judgments

Gender Equality at Home

In Kirti & Anr. v. Oriental Insurance Company Ltd, a three-judge bench in dealing with a life insurance claim of a female homemaker, held that despite the fact that homemakers do not have a fixed income, their contribution to the economy must be recognized. J Ramana in his concurring opinion stated that fixing a notional income for homemakers’ signals to society that the Court is willing to give their labour and sacrifice its due. The judgement paved the way for a novel understanding of fair compensation for women under Article 14.

Cooperative Federalism: Jindal Stainless Steel and Swaraj Abhiyan

In Jindal Stainless Steel v. State of Haryana, a nine-judge bench consisting of J Ramana in the majority, held that imposing entry tax on goods entering from other states is within the right of the States to design their fiscal legislations. They further stated that a tax imposed is prohibited under Article 304(a) of the Constitution only if it is discriminatory in nature. States are well within their rights to impose taxes that act as incentives, when done so in a non-hostile manner. Fiscal legislations drafted with a view of developing economically backward communities do not violate Article 304(a).

In Swaraj Abhiyan (V) v. Union of India a two-judge bench ruled that State governments should implement the National Food Security Act, 2013, which is a Central law. In his supplementary judgment, J Ramana highlighted the principle of cooperative federalism. The Centre and the State are co-equal, but the Constitution also requires them to interact and conduct meaningful dialogue to achieve various constitutional aims.

Right to Express through Internet Recognised; CJI a ‘Public Authority’ under RTI

Justice Ramana wrote the verdict in Anuradha Bhasin vs Union of India, where the legality of the internet shut down and restriction on movement in Jammu & Kashmir was challenged. The Court held that freedom of expression through the internet is inherent to Article 19(1) (a). Justice Ramana noted that the government cannot misuse Section 144 CrPC as a tool to curb expression of opinion or criticism of the government. The three-judge bench also compelled the government to publish every order issued regarding such restrictions and make it public.

A five-judge bench headed by the then Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi upheld the 2010 Delhi High Court Judgement in Central Public Information Officer v. Subhash Chandra Agarwal. They stated that the CJI would come under the ambit of ‘public authority’ in the Right to Information Act, 2005. Justice Ramana in a separate opinion highlighted that RTI should not be used for surveillance of the Court. It should be balanced with judicial independence. This moves the Supreme Court towards transparency and accountability.

‘Horse Trading’ Undemocratic; Collusion to Bid Violates Competition Act

In the Karnataka MLAs case (2019), J Ramana wrote the majority judgment for the three-judge bench. The Court upheld the disqualification of 17 MLAs for defection under the Tenth Schedule of the Constitution of India, 1950. But struck down the Speakers’ bar from letting them contest in elections. He said ‘undemocratic practices’ like ‘horse trading and corrupt practices associated with defection and change of loyalty for lure of office or wrong reasons have not abated’.

In Excel Crop Care Ltd v. Competition Commission of India (2017) a two judge bench ruled that companies who had bid for tenders in collusion had violated the Competition Act, 2002. J Ramana’s supplementary judgment ruled that penalties must be levied not on the total turnover, but only the relevant part that came from the breach of law.

J. Ramana takes over as the CJI, amidst an unprecedented surge in Covid-19 cases in India. The Court has been functioning at a limited capacity since 22 April. This is while pendency has increased massively. He will also have an opportunity to fill 6 vacancies in the Supreme Court and around 230 vacancies for permanent judges in the High Courts.