Analysis

Tell me why

Professor A.K. Mahmudabad was jailed for a Facebook post. The Supreme Court has constituted a Special Investigation Team to decode it

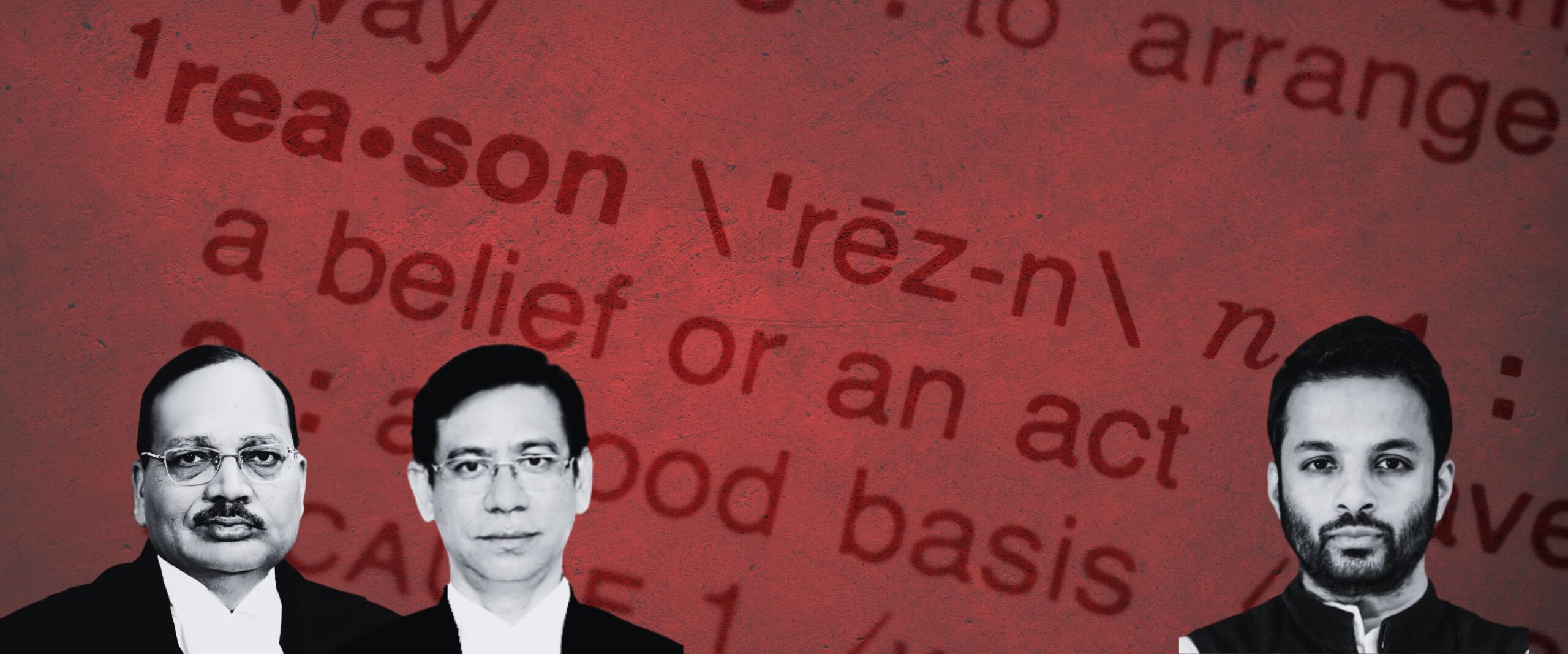

At around noon on Wednesday, in the Supreme Court’s Court Room 2, Justices Surya Kant and N.K. Singh were hearing Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal read out the contents of a Facebook post. Its author is Ali Khan Mahmudabad, a political science professor at Ashoka University. The post is a short commentary on how Operation Sindoor has reset the India-Pakistan equation, and also points out how “deep communalism has managed to infect the Indian body politic.”

Yogesh Jatheri, a sarpanch from Haryana and a general secretary of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s Yuva Morcha, filed an FIR against Mahmudabad for this post. Another FIR was filed by the Haryana State Commission for Women. Mahmudabad is charged with “endangering the country’s sovereignty, unity and integrity,” “promoting enmity between different groups,” causing “public mischief” and “insulting the modesty of a woman.” Mahmudabad challenged these FIRs and his arrest.

In court, his lawyer Sibal argued that the post is “highly patriotic”: the professor lauds the Indian Armed Forces for not targeting “military or civilian installations or infrastructure” and for ensuring that there was “no unnecessary escalation.” He has also condemned the “mindless” advocacy for war by some, pointing out that it is “the poor who suffer disproportionately.”

He then calls on “right wing commentators” who applauded Colonel Sophia Qureshi’s appearance at the press conference to demand, “equally loudly”, that victims of “mob lynchings, arbitrary bulldozing and the BJP’s hate mongering be protected as Indian citizens.” Even as he laments the “grassroots reality that common Muslims face,” the professor notes that the “press conference shows that an India, united in its diversity, is not completely dead as an idea.”

“Where is the criminal intent?” Sibal asked the Court, “The post ends with ‘Jai Hind’.”

Mahmudabad got interim bail. The Court took special efforts to clarify that the Order was only to facilitate the investigation. It’s as if the Court was ensuring that its grant of bail was not construed as disapproval of the arrest. But the professor was asked to surrender his passport and also gagged from writing about the Pahalgam massacre or Operation Sindoor. Further, a Special Investigation Team—headed by an Inspector General of Police—was set up “to holistically understand the complexity of the phraseology employed and for proper appreciation of some of the expressions used.”

This is as far as the reasoning in the Order went. No part of the 400-word Order explained the linguistic “complexity” at hand. Some floaty clues to understand what the Court saw in the post came from Justice Kant’s remarks during the hearing. He suggested that the post was made “deliberately to insult, humiliate or cause discomfort.” He didn’t really explain which words had this effect.

When he asked S.V. Raju to point out the words which insult the modesty of a woman, the Additional Solicitor General vaguely responded that Mahmudabad had made “some” comments against Colonel Qureshi. One guess is that he was referring to the part of Mahmudabad’s post where he says that the “optics of two women soldiers” leading the press conference “must translate to reality on the ground.” The ASG then quickly pivoted the Court’s attention to some paperwork.

When Sibal explained that Mahmudabad’s post speaks of the failings of the Pakistani government, Justice Kant said: “But some words have double meaning also.” The Order itself says nothing about hidden meanings.

The Court wins the public’s allegiance and trust through reasoning. When a university professor is imprisoned for a social media post, there is a high premium on such judicial reasoning. Reasoning allows us to follow the Court’s thinking, discover its research and influences. It helps us make sense of the law and its imperatives, even if we don’t agree with the outcomes. The least we can expect is a serious engagement with logic and the law. In Mahmudabad’s case, as the SIT splits hairs over the Facebook post, we are left wondering just why the Bench chose to go down this path.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!