Analysis

Trick or treaty

Last month’s ruling in the Tiger Global case has triggered a scramble to revisit legacy structures in cross-border transactions

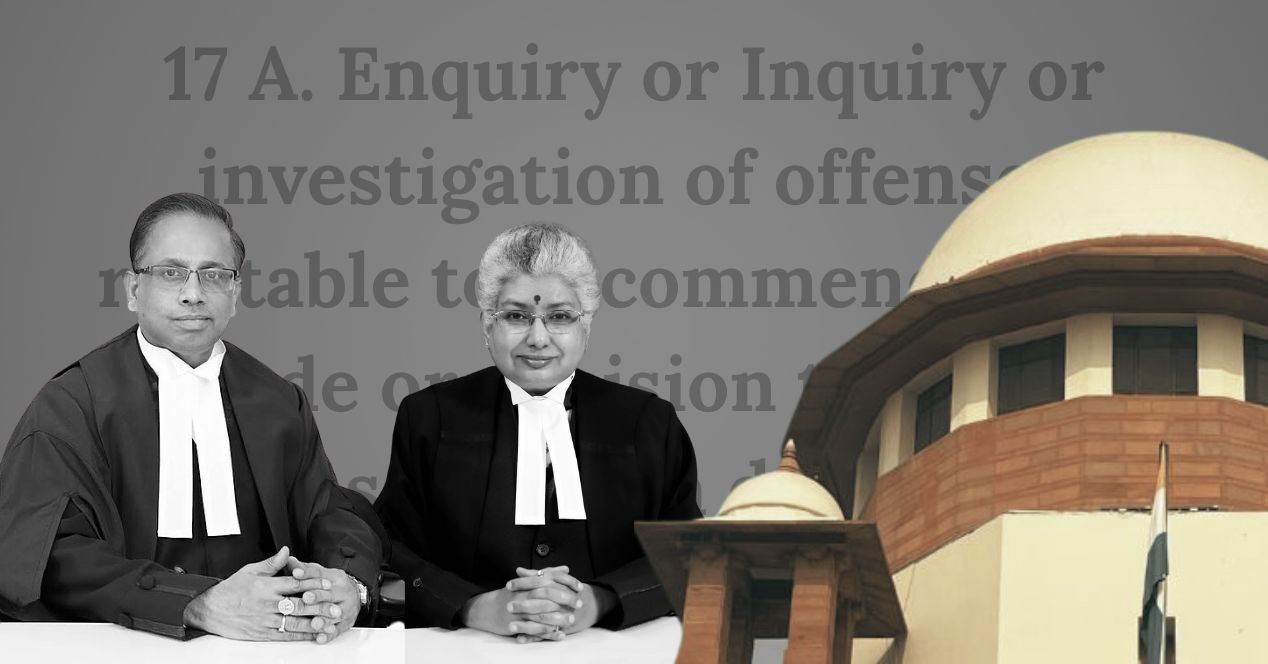

On 15 January, the Supreme Court narrowed the protective scope of the India–Mauritius Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA), holding that investment company Tiger Global’s Mauritius entities could not claim capital gains exemption on their 2018 exit from e-commerce company Flipkart. A Bench of Justices J.B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan held that the transaction was prima facie designed for tax avoidance.

Setting aside a Delhi High Court judgement from August 2024—which had treated Tax Residency Certificates (TRCs) as “sacrosanct”—the Supreme Court restored the Authority for Advance Rulings’ (AAR) conclusion that the structure was an impermissible avoidance arrangement.

The verdict came in appeals filed by the AAR against Mauritius-incorporated entities that sold shares of a Singapore holding company as part of Walmart’s acquisition of Flipkart. The transaction was among the largest offshore exits in India’s startup ecosystem, reportedly yielding proceeds of around ₹14,500 crore. Approximately ₹967 crore was withheld at source by the tax department, which Tiger Global requested be refunded.

Tiger Global claimed exemption from capital gains tax under Article 13 of the DTAA, which grandfathered investments made prior to 1 April 2017, the date of commencement of the General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR). According to the firm, valid TRCs issued by the Mauritian authorities conclusively established treaty entitlement. The tax department disputed this, contending that the transaction involved an indirect transfer structured primarily to secure treaty benefits. The Court, on its part, held that Article 13 was never intended to exempt capital gains arising from the transfer of shares of a company that was neither resident in India nor involved in a direct transfer of Indian assets.

The Delhi High Court had taken a different view. Relying on decisions such as Azadi Bachao Andolan v Union of India (2003) and Vodafone International Holdings BV v Union of India (2012), it held that a TRC constituted sufficient proof of residence and beneficial ownership. It concluded that the Tiger Global entities possessed adequate economic substance in Mauritius and were protected by the treaty’s grandfathering clause.

While rejecting this reasoning, the Supreme Court held that a TRC cannot operate as a “jurisdiction-ousting device” that forecloses scrutiny of the true nature of an arrangement. Treaty benefits, the Court noted, rest on substantive entitlement and cannot survive where an arrangement lacks

“commercial substance”. The Bench accepted that effective control and management of the entities lay outside Mauritius, applying the “head and brain” test to conclude that the Mauritian companies functioned as conduit or “see-through” entities.

The Court held that Chapter X-A of the Income Tax Act constitutes a self-contained anti-abuse framework that can override treaty benefits by virtue of Section 90(2A). Yet the transaction itself predates GAAR’s commencement. While GAAR was not applied formally, the Court relied on avoidance-based concepts—such as lack of commercial substance and conduit arrangements—to deny treaty protection at a threshold stage, raising concerns about how pre-GAAR transactions may be scrutinised going forward.

The verdict has also reopened questions around indirect transfers under tax treaties. When India introduced indirect transfer provisions in 2012, the Finance Minister clarified that they would not override treaty protections. Even in this case, the tax department accepted that indirect transfers fall within the residuary clause of Article 13. From the standpoint of tax administration, the verdict is seen as restoring balance between treaty interpretation and domestic anti-avoidance policy. Critics, however, warn that it opens “unjustifiable windows” to examine offshore deals.

What is clear is that incorporation documents and TRCs will no longer suffice to secure treaty protection. Courts and tax authorities are likely to look into where decision-making authority lies and whether the treaty residence reflects genuine commercial substance. In that context, Justice Pardiwala’s observation that “taxing an income arising out of its own country is an inherent sovereign right” may sound to foreign investors less like a statement of principle and more like a warning.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!