Unexecuted Sales Deed Cannot Exclude Property from Matruka

Zoharbee v Imam Khan

Case Summary

The Supreme Court held that an unexecuted agreement to sell cannot exclude immovable property from a “matruka”—property left behind without a will in Mohammedan law. It stated that Section 54 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882, confers no rights nor vests any interest in another party unless an agreement...

Case Details

Judgement Date: 16 October 2025

Citations: 2025 INSC 1245 | 2025 SCO.LR 10(3)[15]

Bench: Sanjay Karol J, P.K. Mishra J

Keyphrases: Section 54—Transfer of Property Act, 1882—agreement to sell—matruka property—mohammedan law—unexecuted sale deed cannot exclude property from matruka—appellant entitled to only transfer her share—High Court and First Appellate Court Orders upheld

Mind Map: View Mind Map

Judgement

SANJAY KAROL, J.

1. In these appeals, challenge is laid to final judgment and order dated 1st March 2012 in Second Appeal No.435 of 2011 with Civil Application No.10306 of 2011 passed by the High Court of Judicature at Bombay, Bench at Aurangabad whereby the appellants assailed the order of the First Appellate Court in RCA No.87 of 20051 dated 4th March 2005, overturning the findings of the Civil Court2, was rejected.

2. The short conspectus of facts is that the appellant’s husband namely Chand Khan passed away and now this litigation pertains to the property he left behind, between his surviving spouse namely Zoharbee3 and his brother i.e. Respondent Imam Khan4. The plot of land which is germane to the dispute is land S.No.22/3 and 22/1 of Gut No. 107 and Gut No.126. It is the plaintiff’s case that all the property left behind by the deceased Chand Khan is matruka property and since he died issueless, as per Mohammedan law the former would be entitled to 3/4th of the total property and only the remaining 1/4th would fall in the rights and entitlements of defendant no.1. On the other hand, the case as per defendant no.1 is that the land bearing gut no.126 already stood transferred to the third party in the lifetime of Chand Khan by an Agreement to Sell dated November 1999 with defendant no.2 and 3 namely, Pandit Fakirrao Bodkhe and Bhausaheb Fakirrao Bodhke, and so the said property cannot be the point of contention in the instant proceedings. In so far as the other piece of land is concerned, it is contended that the same stood transferred to the sole and exclusive ownership and possession of defendant no.1 many years prior to the death of Chand khan but in the challenging circumstances of the latter’s continued illness, the same was sold to one Ayub Khan who is defendant no.4 and part consideration of such sale stood received in the life of Chand Khan and the remaining, subsequently after his death. Therefore, nothing remains to be partitioned in terms of matruka property.

3. The learned Civil Court agreed with the contentions of defendant no.1 and partly decreed the plaintiff’s suit in so far as the property sold to defendant no.4 is concerned for the reason that he chose not to contest the suit in any way whatsoever and did not file a written statement. Regarding the remaining property, it was observed that the Agreement to Sell entered into between the parties in the lifetime of Chand Khan stood duly proved by way of examination of witnesses (defendant no.2 and 3) and, therefore, no property remained to be divided between the successors in interest of the deceased. It was acknowledged that the sale deed was executed by Zoharbee after Chand Khan had died however the said fact was not treated as material in view of the evidence presented.

4. The plaintiff, being aggrieved, filed the first appeal under Section 96 of the Code of Civil Procedure. The First Appellate Court vide judgment dated 30th June 2011 reversed the findings of the Civil Court and held that the plaintiff’s suit was entirely maintainable. In other words, the plaintiff would be entitled to 3/4th of the total property in the name of the deceased. A further reason for arriving at such a finding was that an Agreement to Sell does not confer any right. The rights would stand vested with the third party only upon the execution of the sale deed which was done after his death. At the time of death therefor, the property was still vested in Chand Khan.

5. In Second Appeal, by way of the impugned judgment, it is recorded that no substantial question of law arises for consideration. The learned Single Judge thereafter proceeds to consider the contentions raised by either side which, for the defendant no.1 are the points that were raised before the learned Civil Court and on behalf of the plaintiff were those that were raised before the First Appellate Court. Although we have some reservations with the fact that the learned Single Judge proceeded to examine the contentions on merit despite arriving at a finding that no substantial question arose for consideration, we proceed further. Suffice it only to say that when a Court is of the view that no substantial question arise it has no choice but to dismiss, in limine the appeal-but still has to give reasons therefor. [See: Surat Singh (dead) v. Siri Bhagwan 2018 (4) SCC 562 and Hasmat Ali v. Ameena Bibi & Ors. 2021 SCC Online SC 1142].

6. Two issues arise for consideration one, whether the agreement to sell in so far as one portion of the property would be sufficient to exclude the same from the scope and expands of matruka property to be partitioned at the time of his death and second whether the properties of deceased Chand Khan qualify as matruka properties within the meaning of Mohammedan law.

7. An agreement to sell does not confer any rights nor does it vest any interest into the party that agrees thereby to buy a particular property. This is a well acknowledged position in law. In Suraj Lamp & Industries (P) Ltd. (2) v. State of Haryana, (2012) 1 SCC 656, the law was clarified as follows:

“16. Section 54 of the TP Act makes it clear that a contract of sale, that is, an agreement of sale does not, of itself, create any interest in or charge on such property. This Court in Narandas Karsondas v. S.A. Kamtam [(1977) 3 SCC 247] observed:

(SCC pp. 254-55, paras 32-33 & 37)

“32. A contract of sale does not of itself create any interest in, or charge on, the property. This is expressly declared in Section 54 of the Transfer of Property Act. (See Ram Baran Prasad v. Ram Mohit Hazra [AIR 1967 SC 744 : (1967) 1 SCR 293] .) The fiduciary character of the personal obligation created by a contract for sale is recognised in Section 3 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963, and in Section 91 of the Trusts Act. The personal obligation created by a contract of sale is described in Section 40 of the Transfer of Property Act as an obligation arising out of contract and annexed to the ownership of property, but not amounting to an interest or easement therein.

33. In India, the word ‘transfer’ is defined with reference to the word ‘convey’. … The word ‘conveys’ in Section 5 of the Transfer of Property Act is used in the wider sense of conveying ownership.

***

37. … that only on execution of conveyance, ownership passes from one party to another….”

17. In Rambhau Namdeo Gajre v. Narayan Bapuji Dhotra [(2004) 8 SCC 614] this Court held: (SCC p. 619, para 10)

“10. Protection provided under Section 53-A of the Act to the proposed transferee is a shield only against the transferor. It disentitles the transferor from disturbing the possession of the proposed transferee who is put in possession in pursuance to such an agreement. It has nothing to do with the ownership of the proposed transferor who remains full owner of the property till it is legally conveyed by executing a registered sale deed in favour of the transferee. Such a right to protect possession against the proposed vendor cannot be pressed into service against a third party.”

18. It is thus clear that a transfer of immovable property by way of sale can only be by a deed of conveyance (sale deed). In the absence of a deed of conveyance (duly stamped and registered as required by law), no right, title or interest in an immovable property can be transferred.

19. Any contract of sale (agreement to sell) which is not a registered deed of conveyance (deed of sale) would fall short of the requirements of Sections 54 and 55 of the TP Act and will not confer any title nor transfer any interest in an immovable property (except to the limited right granted under Section 53-A of the TP Act). According to the TP Act, an agreement of sale, whether with possession or without possession, is not a conveyance. Section 54 of the TP Act enacts that sale of immovable property can be made only by a registered instrument and an agreement of sale does not create any interest or charge on its subject-matter.”

(emphasis supplied)

Holding in Suraj Lamp (supra) was recently followed in RBANMS Educational Institution v. B. Gunashekar, 2025 SCC OnLine SC 793.

8. In view of the above, the view taken by the First Appellate Court and the High Court cannot be faulted with. The property agreed to be sold was, at the relevant time still the property of Chand Khan and therefore would be subject to division of property as per the applicable law. In other words, said property would form part of ‘matruka’ property which has been defined by the Courts as under:

In Jamil Ahmad v. Vth ADJ, Moradabad, (2001) 8 SCC 599:

“11. The property (both movable as well as immovable) left by a deceased Muslim is called matruka. The scheme of distribution of matruka among the heirs of a deceased Muslim is that first that part of the matruka which is covered by a will of the deceased, if there is a valid will (subject to a maximum of 1/3rd of the total matruka provided it is not in favour of an heir) will be separated and given to the legatee. The balance of matruka alone is distributable among the heirs and in the proportion ordained under the Mohammedan law. However, in regard to bhumiswami land the distribution of matruka will be governed by Sections 169 and 171 of the ZALR Act. Consequently the limitation placed under the Mohammedan law that the bequest should not exceed 1/3rd of the matruka of the deceased and it should not be in favour of an heir, will not apply; so also classification of heirs and the proportion in which they will inherit matruka under the Mohammedan law is replaced with the provisions of Section 171 of the ZALR Act in which a different order of succession is provided.”

(emphasis supplied)

A judgment of fairly recent vintage also refers to the pronouncement above. In Trinity Infraventures Ltd. V. M.S. Murthy, 2023 SCC OnLine SC 738, it was observed:

“93. Before we proceed further, it may be necessary to decode certain words and expressions used in these proceedings from the beginning. If not, they will continue to haunt and frighten the reader. Therefore, a glossary is presented as under:

(i) Matruka: The property, both movable as well as immovable left by a deceased muslim is called Matruka

9. Reference may also be made to John T Platts’ A Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi and English’5 which defines ‘matruka’ as the estate of a deceased person. Also, as per the Rekhta Dictionary, ‘matruka’ is a word of Arabic origin and means “abandoned from his possession (property etc.)[,] left by immigrants (property etc.) [,] inherited wealth and property etc.6. It is clear from the above that matruka property simply refers to property left behind by deceased person and nothing more. Regarding the devolution of matruka property, it has to be observed that the Will is the first document that is to be satisfied subject to the limits imposed by Muslim Law, namely, that it cannot exceed one-third of the estate and cannot ordinarily be made in favour of an heir without the consent of the other heirs, and then whatever remains hereafter, is to be distributed strictly as per the rules of intestate succession prescribed in Muslim Law.

10. Since the Agreement to Sell has no value in the eyes of law, all the property that vested in Chand khan would become matruka property. The next question then to be considered is as to how the division thereof would take place.

11. In Mohammedan Law, the division of property is well defined. The Holy Quran itself delineates how division of property is to take place. Chapter IV, Verse 12 reads as under:

“And for you is half of what your wives leave if they have no child. But if they have a child, for you is one fourth of what they leave, after any bequest they [may have] made or debt. And for the wives is one fourth if you leave no child. But if you leave a child, then for them is an eighth of what you leave, after any bequest you [may have] made or debt. And if a man or woman leaves neither ascendants nor descendants but has a brother or a sister, then for each one of them is a sixth. But if they are more than two, they share a third, after any bequest which was made or debt, as long as there is no detriment [caused]. [This is] an ordinance from Allah , and Allah is Knowing and Forbearing.”7

12. It would also be useful to, at this stage, refer to Mulla Principles of Mahomedan Law8 which in this regard says as follows:

Ҥ51. Heritable property There is no distinction in the Mahomedan law of inheritance between movable and immovable property or between ancestral and self-acquired property.

…

A. THREE CLASSES OF HEIRS

§ 61. Classes of heirs There are there classes of heirs, namely, (1) Sharers, (2) Residuaries, and (3) Distant Kindred:

(1) “Sharers” are those who are entitled to a prescribed share of the inheritance;

(2) “Residuaries” are those who take no prescribed share, but succeed to the “residue” after the claims of the sharers are satisfied

(3) “Distant Kindred” are all those relations by blood who are neither Sharers nor Residuaries.

…

B. SHARERS

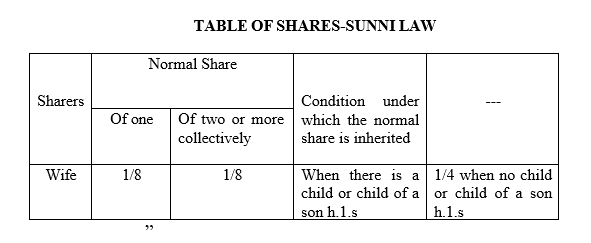

§ 63. Sharers- After payment of funeral expenses, debts, and legacies, the first step in the distribution of the estate, of a deceased Mahomedan is to ascertain which of the surviving relations belong to the class of sharers, and which again of these are entitles to a share of the inheritance, and, after this is done, to proceed to assign their respective shares to such of the sharers as are, under the circumstances of the case, entitled to succeed to a share. The first column in the accompanying table contains a list of sharers; the second column specifies the normal share of each sharer; the third column specifies the conditions which determine the right of each sharer to a share, and the fourth column sets out the shares as varied by special circumstances.

13. The first and foremost thing to be accomplished with the estate of a deceased person is the payment for expenses, debts and legacies. Thereafter, comes allotment of shares to such relations who are entitled to a prescribed share. What follows is that if any part of the estate remains, the same is divided among the residuaries. Should there be a situation where there are no sharers, the residuaries will come into the entirety of the inheritance. It is further provided that if there are neither sharers nor residuaries, ‘distant kindred’ shall be entitled to the same.

14. A perusal of the above extracted principles of Muslim Law of inheritance depicts that the sharers are entitled to a prescribed share of the inheritance and wife being a sharer is entitled to 1/8th the share but where there is no child or child of a son how low so ever, the share to which the wife is entitled is 1/4th.

15. Since the rules governing inheritance are clear and there is no room for subjective analysis, the proportions assigned have to be necessarily followed. The property in question is unquestionably matruka property and so has to be distributed amongst the survivors of Chand Khan, as per the principles laid down in this regard. The Civil Court, therefore, clearly fell in error taking into consideration an incomplete sale wherein the sale deed had not been executed and excluding the said property from the total that had to be divided. Additionally, we may also observe that the defendant no.1, in executing the sale deed had the right only to do so in respect of the 1/4th share that fell in her share and not the entire property for the maxim governing such transactions is nemo dat quod non habet which translates to no one can transfer a better title onto another than what they themselves have.

16. Consequent to the above discussion, it has to be held that the First Appellate Court and the High Court took the correct view in law. As such no interference is called for.

17. Before parting with the matter, we record our dissatisfaction with the manner in which the judgment of the learned Civil Court was translated into English. In matters of law, words are of indispensable importance. Each word, every comma has an impact on the overall understanding of the matter. Due care has to be taken to ensure that the true meaning and spirit of the words in the original language are translated into English for the Courts in appeal to comprehend what had transpired below. Just recently, a Co-ordinate bench also highlighted similar concern vide order dated 18th March 2025 in Chairman Managing Committee & Anr v. Bhaveshkumar Manubhai Parakhia & Anr. We may only underscore the observations made therein.

18. Appeals are dismissed. No costs. Pending application(s), if any, stands disposed of.

- District Judge, Aurangabad [↩]

- 2nd Jt. Civil Judge (J.D.) Aurangabad in RCS No.310/99 [↩]

- Hereinafter Defendant No.1 [↩]

- Hereinafter Plaintiff [↩]

- Digital Dictionaries of South Asia, University of Chicago, See: https://dsal.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/app/platts_query.py?page=992 [↩]

- https://www.rekhtadictionary.com/meaning-of-matruuka [↩]

- https://legacy.quran.com/4/12#:~:text=And%20for%20you%20is%20half,may%20have% 5D%20made%20or%20debt. [↩]

- 22nd Edition [↩]