Analysis

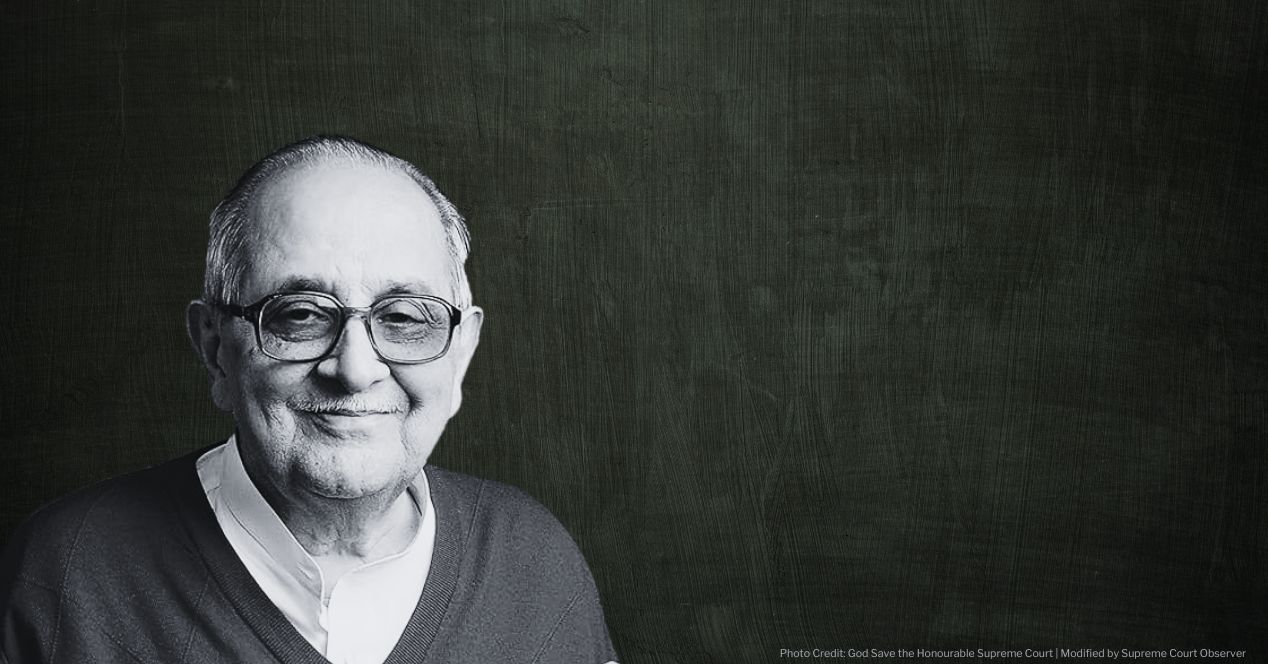

Manohar Lal Sharma: The man who kept knocking on the Supreme Court’s doors

What the career of the serial PIL petitioner—who passed away on 19 December—tells us about the contemporary Supreme Court

On 19 December 2025, Manohar Lal Sharma passed away at the age of 69 after suffering from a kidney ailment. He occupied a curious and contested space in the Supreme Court’s public law ecosystem. For more than a decade, Sharma was instantly recognisable as the advocate who perpetually rushed to the Court with a public interest petition on almost every major political, constitutional or policy controversy of the day.

From Rafale to Pegasus, demonetisation to electronic voting machines, Sharma’s filings often arrived with striking speed, sometimes ahead of detailed public discourse, and before formal institutional responses had crystallised. He was the lone advocate who could, by force of insistence and timing, place politically charged questions at the doors of the Supreme Court.

To admirers, he embodied the lone citizen-lawyer who refused to wait for elite consensus before invoking the Constitution. To critics, he was a serial filer, who represented a style of litigation driven as much by publicity and timing if not by doctrinal rigour: One that was too quick to convert headlines into writ prayers, and too comfortable with petitions that seemed designed less to win final relief than to provoke a hearing, or an interim observation.

Why did the Supreme Court repeatedly entertain Sharma’s petitions, even as it grew increasingly vocal about curbing motivated or repetitive public interest litigation? In a 2021 judgement surveying PIL’s expansion, the Court reiterated its earlier observation that the PIL “balloon should not be inflated so much that it bursts” adding that the jurisdiction should not be “allowed to degenerate to becoming publicity interest litigation or private inquisitiveness litigation”.

Sharma was not an outsider who could be blamed for procedural ignorance. He understood the mechanics of mentioning, listing and urgency, and grasped how judicial time and public attention now interact. His petitions were often spare, occasionally speculative, and vulnerable to facts. Yet, they consistently invoked a vocabulary the Court has long found difficult to ignore: constitutional conscience, fundamental rights and the urgency of executive accountability.

Critics argued that his tactic compressed complex questions into urgent hearings without adequate factual scaffolding. Supporters countered that strategic immediacy was not an abuse but a corrective in a system where inertia often shields executive action from scrutiny.

Since the late 1970s, the Supreme Court has oscillated between radical openness and defensive gatekeeping. In recent years, benches have repeatedly warned against “busybody” petitions and “ambush” litigation. The phrase “ambush petition” is not merely rhetorical. It is timed and structured to extract the institutional value of a hearing even if its merits are thin, and to convert the fact of judicial engagement into public legitimacy.

Well-established organisations such as the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) have faced pointed judicial questions about frequency of filing and alleged agenda-setting. Yet, even in those instances, when Sharma’s petitions were dismissed at the threshold, his bona fide was not suspected. He was criticised, sometimes sharply, but the Court seemed to tolerate his petitions, and avoided imposing costs on him, because he was one of its practising advocates.

Instances, when fined

Sharma was not always lucky. He was fined by the Court on four instances:

In 2012, the Supreme Court slapped Sharma with a fine of Rs. 50,000 for a petition that alleged a conflict of interest against then Chief Justice S.H. Kapadia in the Vodafone case.

In July 2014, the Court imposed another fine of Rs. 50,000/- in a petition where Sharma challenged the government’s decision to sell its stake in Hindustan Zinc Ltd. to the Vedanta Group. The fine was later reduced to Rs. 25,000/- after he requested for leniency.

In September 2014, however, the Court declined a similar gesture, and imposed an exemplary cost of Rs. 50,000/- for raking up the issue of the mysterious disappearance of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose.

In 2018, the Court rejected a petition raising allegations against the then Finance Minister, late Arun Jaitley relating to the capital reserve of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). It imposed a fine of Rs. 50,000/- and directed the Court Registry to not accept any petitions from Sharma unless he paid it.

Reason for indulgence

In several high-profile episodes, his petition became the entry point for constitutional scrutiny. Courts often experiment with individual litigants because the reputational stakes are lower. Sharma carried no institutional baggage beyond his own name.

In many cases, the Court used his petitions instrumentally, separating him from the questions raised. The ambush may have triggered the hearing, but the Court retained control over the narrative and outcome.

Filing for Sharma was not merely procedural; it was expressive. Yet to many, his style acknowledged the risk of excess, where urgency eclipses deliberation. The Court’s tolerance of frequent, somewhat under-prepared petitions blurred the line between constitutional adjudication and political theatre.

Observers have noted that Indian courts have historically been more indulgent toward individual petitioners than toward institutions, which are often suspected of pursuing agendas. Sharma benefitted from this asymmetry. Organisations arrive with reputational capital, research frameworks and the implicit claim to sustained oversight. Individuals, by contrast, are more easily framed as acting from conscience rather than strategy.

There was also a pragmatic dimension. When an organisation like ADR approaches the Court, judicial engagement risks signalling endorsement of a continuing supervisory role. With an individual petitioner, the Court can listen, probe and disengage with fewer institutional consequences.

This dynamic was particularly evident in the Pegasus litigation. While the Court resisted demands for wholesale disclosure and declined to accept allegations at face value, it used the petitions to frame constitutional concerns around surveillance, privacy and executive accountability. This ultimately led to the constitution of an independent committee. His lead petition functioned less as a vehicle for final relief than as a trigger for institutional inquiry.

Law officers have often cautioned the Court that entertaining petitions based largely on media reports risked judicial overreach into domains such as national security and executive policy.

Sharma’s career exposed the Court’s unresolved ambivalence about PIL itself. He tested the outer limits of access, sometimes to the Court’s discomfort, sometimes to its utility. Sharma will be remembered more as a procedural catalyst, and at times an enabler of constitutional conversation. His life at the Bar ultimately tells a larger story about the contemporary Supreme Court: an institution wary of being used, yet repeatedly willing to listen; cautious about publicity, yet responsive to urgency; critical of excess, yet unable to fully close its doors to the citizen who arrives knocking at precisely the right moment.