Analysis

Do former judges make better arbitrators?

In this excerpt from his essay on the SC and arbitration, Amit George details pressing issues around judicial intervention and restraint

Fali Nariman, one of India’s most distinguished jurists and an internationally recognized authority on international arbitration, once aptly reflected on the Indian Arbitration Act, 1940 (1940 Act), drawing from Russell’s classic work on arbitration to highlight the enduring friction between two seemingly irreconcilable phenomena: the pursuit of justice, on the one hand, and the threat of endless litigation, on the other. His observation succinctly captures the challenges that plagued arbitration under the 1940 Act: ‘In India we have had our Arbitration Act since 1940—it governs domestic and reaches out to foreign arbitrations as well; it is based on the ‘high principle’ and the party losing never lets the Court forget it!’

Nariman further stated that arbitration under the 1940 Act rarely concluded with the issuance of the award. It often extended into prolonged litigation as parties routinely challenged awards in India’s multi-tiered judicial system. He further remarked that there was a noticeable tendency among courts to approach arbitration with a distinct pro-court bias, adopting a mindset that was ‘supervisory, almost schoolmasterly’. This, he observed, reflected an ‘indulgent and paternalistic’ attitude towards arbitration.

While India’s journey in arbitration law may have been marred by inefficiencies, procedural delays and judicial overreach (discussed later in this essay), there has been a concerted push for positive reform, albeit with certain persisting inconsistencies, in the arbitration ecosystem, with the enactment of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (1996 Act) and subsequent amendments thereto. Throughout this evolution of the arbitration landscape over the years, the Supreme Court of India (SCI) has played a pivotal role in shaping the course of the law in the country. While significant improvements have been driven by the SCI, its polyvocal character has led to legal uncertainties, that is, the diverse perspectives emanating from different benches have resulted in ambiguity as regards the scope of judicial intervention in arbitration. This essay traces the journey of arbitration law in India and reflects on the SCI’s role in shaping it over the past seventy- five years. It also briefly traces early setbacks encountered in the arbitration regime, the many ways in which India overcame these setbacks, and the turning points in arbitration law that culminated in the legal framework we have today. In the end, it proffers certain measures that would assist in further enhancing India’s position as a global arbitration player.

Considering the period under review and the large amount of judicial precedent that must be engaged with, the scope of the present essay is confined to examining the SCI’s approach to award-challenge proceedings over the years. The essay explores aspects intrinsically linked to the legal framework governing such proceedings such as the modification of awards, the requirement of reasons in either upholding or setting aside an award, the scope of the ‘public policy’ doctrine, and other grounds for judicial intervention with arbitral awards. As an arbitral award reflects the culmination of the arbitration process, an analysis of the jurisprudence generated in award-challenge proceedings provides a cogent barometer of the SCI’s overall attitude towards alternative dispute resolution processes, in general, and arbitration, in particular.

***

1996 Act: Transition to a New Regime

With the liberalization of the Indian economy and the advent of globalization, the provisions under the 1940 Act were no longer equipped to meet the evolving requirements of India’s modern economic framework. There was widespread demand across various sectors for an overhaul of the outdated arbitration laws as they were widely considered archaic and insufficient to meet the demands of a modern economy. The 1940 Act provided little contemporary value, and the calls for reform were strongly supported by associations in business and commerce as well as the judiciary.

The need for a new legal framework in arbitration was also advocated by the CJI. In furtherance of the same, in 1995, the Minister of Law, Justice and Company Affairs introduced a Bill in the Rajya Sabha to implement the UNCITRAL Model Law within Indian arbitration laws and also give statutory recognition to conciliation. However, due to other legislative priorities, the Parliament did not take up the Bill. Consequently, when the Parliament was not in session, the President of India promulgated the new arbitration law through an Ordinance. There was, thus, a substitution of the 1940 Act by the 1996 Act to, among other things, address the challenges posed by the contemporary international trade and commercial landscape.

The 1996 Act was designed to foster trade by ‘a unified legal framework for the fair and efficient settlement of disputes arising in international commercial relations’. It sought to address the needs of foreign investors and businesses and showcased Parliament’s effort to harmonize India’s legal system with its economic policy goals. From the outset, the SCI emphasized the distinct and forward-looking nature of the 1996 Act. In Sundaram Finance v. NEPC India, the Court categorically noted that the 1996 Act ought to be interpreted in light of the UNCITRAL Model Law—on which it was based—and should remain ‘uninfluenced by the principles underlying the 1940 Act’.

What the Numbers Reveal

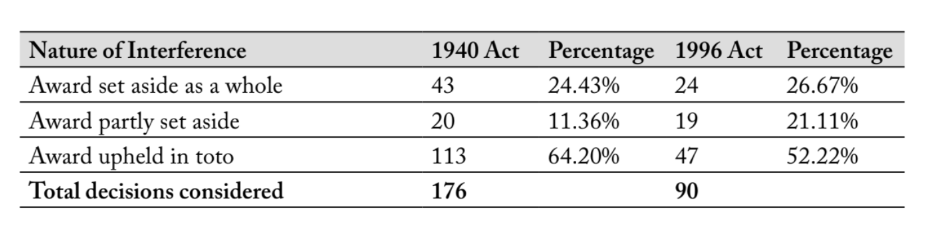

To carry out a data-based comparison of the extent of interference under the 1940 Act and the 1996 Act, an analysis of 176 decisions under the 1940 Act and ninety decisions under the 1996 Act, emanating from the SCI, was undertaken during the course of research for the present essay. Under the 1940 Act, 64.20 per cent of the arbitral awards surveyed (out of the sample size of 126) were found to have been upheld in toto. However, under the 1996 Act, only 52.22 per cent of the arbitral awards (out of a sample size of 90) were found to have been upheld in toto. A table fleshing out the aforesaid data, and revealing the extent and nature of interference under the 1940 Act and 1996 Act as reflected from the judgments of the SCI, is as under:

It is important to appropriately caveat the data reflected in the aforesaid table. Insofar as the 1996 Act is concerned, the table excludes decisions where only the interest awarded by the arbitral tribunal was assailed and subsequently set aside or modified. Insofar as the 1940 Act is concerned, in addition to the aforesaid exclusion, only instances of setting aside—and not the limited modification as contemplated under Section 15 of the 1940 Act—have been considered.

With the aforesaid caveats in mind, an analysis of the data reveals that the tendency to interfere with arbitral awards—at least in the context of a partial setting aside—has seen a significant upswing under the 1996 Act, quite contrary to the general understanding that the regime under the 1996 Act has seen a more hands-off approach to an arbitral award as compared to the regime under the 1940 Act.

Charting the Path Forward

Assessing Awards for Quality: A Challenge

Commentators note that minimal judicial intervention, one of the primary objectives of the Model Law, would only be effective when courts are confident that qualified arbitrators have been appointed and the arbitration proceedings have been properly conducted. It has also been stated that ‘the secret to a relationship that is beneficial to both arbitral tribunals and people would be to encourage but not to interfere’.

Arbitration in India lacks formal mechanisms for ranking arbitrators or evaluating the substantive quality of arbitral awards. Unlike in traditional litigation, arbitrators function within a relatively insulated framework. Arbitral awards are largely shielded by confidentiality principles, which limit external evaluation of their quality. The absence of a ranking or quality benchmark poses challenges for parties in selecting arbitrators whose competence and impartiality are assured. As is evident from the discussion in the preceding part of the present essay, the extent of interference with arbitral awards by the SCI reflects a lingering distrust in the arbitration process being able to achieve a just result.

A structured, qualitative ranking system for arbitrators—grounded not merely in volume or length of service but also in factors such as expertise, efficiency, party satisfaction and impartiality—could improve transparency and accountability, as also instil greater trust in the arbitration process as a whole. Such a framework would provide objective criteria for determining arbitrators’ suitability based on dispute-specific requirements. Without such benchmarks, the risk persists that parties may appoint arbitrators based more on reputation than actual expertise or field-specific competence, which may impact both the quality and finality of arbitral awards.

Whether Former Judges Make for Better Arbitrators?

The prevailing practice of courts largely favouring the appointment of retired judges as arbitrators has raised concern and has been viewed by some as an extension of patronage. Under Section 11 of the 1996 Act, the law only requires that arbitrators meet qualifications in the arbitration agreement, and otherwise leaves their selection to the discretion of the appointing court. Therefore, there is no systematic methodology followed by Indian courts while appointing arbitrators. This can result in the appointment of retired judges as arbitrators who follow rigid court-like procedures or may lack field-specific experience or technical expertise, which can lead to delays in grasping complex issues. Another recurring issue with appointing retired judges as arbitrators is the over-reliance on a select group of well-regarded former judges, which leads to limited availability of dates for hearings, especially with three-member tribunals. This trend warrants reform to ensure that the legitimacy of the appointment process as enshrined under Section 11 of the Act remains intact.

This approach also indicates a lack of trust in appointing lawyers or other professionals as arbitrators—a trend less prevalent in jurisdictions like the UK, where barristers and specialists from other disciplines often serve as arbitrators. Similarly, in the American Arbitration Association’s panels of arbitrators, a diverse group of professionals—including lawyers specializing in commercial arbitration, professors, and various industry experts such as accountants and managers—comprise the pool from which arbitrators are chosen. Such diversity is important for selecting arbitrators based on expertise suited to the specific field of dispute where retired judges may not always be the most appropriate choice.

Practitioners also express concern over what they perceive as encroachment in the larger alternative dispute resolution field by former judges. Concerns have been raised that this trend also compromises the perceived impartiality and independence of the alternative dispute resolution ecosystem within the country as a whole.

The prevailing perception that only retired judges are competent to handle arbitrations constrains the arbitration process. Expanding the pool to include experienced lawyers and specialists—an approach increasingly being adopted by various Indian arbitration institutions through their panel of arbitrators—could improve the overall efficiency in arbitration. In fact, L Nageswara Rao J, former judge of the SCI, also stated: ‘Why is it only judges are appointed as arbitrators by the courts? For the past one and a half years after my retirement, I have been speaking at various podiums outside this country also that it is time that Indian courts should shed this habit of only appointing judges as arbitrators. There are legal professionals of various age groups who have experience in arbitration who should be appointed’.

Alternative dispute resolution initiatives should prioritize development and resolution of disputes over other interests. This would mitigate the perception that alternative dispute resolution has become a channel of patronage for retired judges and help foster public trust in alternative dispute resolution. While retired judges undoubtedly bring to the table a wealth of legal knowledge and experience, an untrammelled preference for only one stream or source of appointment of arbitrators compromises the efficacy of the arbitration process.

The Role of the Bar

The role of the Bar in streamlining arbitration cannot be overstated, yet it is often overlooked. From selecting competent arbitrators to setting appropriate expectations with clients about the finality of awards and the limited scope of judicial review, lawyers play a pivotal role at every stage of arbitration proceedings. In India, litigants’ tendency to pursue litigation and seek ‘another bite at the cherry’ all the way up to the SCI exacerbates the already overwhelming backlog of cases, and fosters a negative culture of litigation and appeals. This practice effectively reduces constitutional courts to mere appellate bodies and encourages litigants to ‘gamble’ on a different outcome at every possible level. As officers of the Court, lawyers bear a professional responsibility to avoid dilatory tactics that diminish the efficacy of arbitration as an alternative means of dispute resolution.

Furthermore, Bar associations could consider developing training programs and certifications for lawyers engaged in arbitration—particularly for younger practitioners. Through such initiatives, Bar associations would not only foster specialized skills within the Bar but would also help cultivate an arbitration culture that avoids imitating court-like processes such as lengthy procedures as well as excessive formalities and that preserves arbitration as a quicker and more efficient alternative to traditional litigation.

Conclusion

The history of the SCI, in terms of how it has approached arbitration over the past seventy-five years, has been marked by an inconsistent approach, with different Benches taking divergent positions. This is reflective of the subject- matter dichotomy faced by the SCI as it frequently finds itself delving into intricacies of contractual interpretation and evidentiary issues in arbitration matters, notwithstanding its role as the constitutional court of last resort.

Although the SCI has, particularly after the enactment of the 1996 Act, generally espoused a policy of minimal judicial interference, significant inconsistencies persist. While there has been a noticeable shift in attitude, especially in reducing the distrust that previously clouded arbitral awards, the broader issue of judicial intervention remains unsettled and the numbers reveal a worrying picture. Certain instances of judicial interference by the SCI negatively affected India’s standing as a viable seat for international commercial arbitrations, thereby necessitating the need for course correction by both the judiciary and the legislature. This culminated in the 2015 Amendment, followed by several decisions of the SCI that further clarified the law on the limited scope of judicial intervention in arbitral awards to reinforce the pro-arbitration stance of Indian courts.

Legislative reforms in the last decade have been important milestones in shaping arbitration in India. However, it must be recognized that legislative amendments alone are insufficient. Progress will only be achieved when the judiciary, legislature and other stakeholders undergo a corresponding attitudinal shift. In this endeavour, the SCI’s pivotal role, and the role of courts in general, is evident from the fact that matters concerning patent illegality or public policy are predominantly governed by judicial discretion. Simultaneously, a more objective application of the public policy test is necessary. The golden rule—that an arbitral award, whether domestic or international, must be enforced unless exceptional circumstances exist—must be reinforced. This will minimize court interference and promote the finality of arbitral awards. Therefore, by resisting the temptation to reassess the merits of arbitral awards, courts can help position India as a preferred arbitration destination.

It is laudable that Indian courts have taken steps to address long-standing inefficiencies by setting up dedicated Arbitration Benches to tackle the backlog. While India has gained momentum in developing institutional arbitration across the country in recent years, much remains to be done. To ensure that India emerges as a preferred destination for arbitration, courts must resist the temptation to reassess the merits of awards.

In 2021, the then CJI remarked that, ‘[a]ll the Foreign Investors requested only one thing. They said that they were ready to invest but were afraid of litigation […] In case by any chance, they get themselves involved in litigation, they want it to be resolved easily, amicably and without any time lag so that their investment is saved’. The statement reflects the foreign investors’ concerns about the unpredictability of litigation in India. Only time will tell whether these concerns have been effectively addressed or if the narrative of improvement is merely theoretical, with little tangible progress on the ground. Whether India will succeed in becoming an internationally coveted seat for commercial arbitration—an ambition that has only been partially realized so far—remains to be seen. The coming years will reveal if India can consistently build, maintain, and strengthen its pro-arbitration stance—and the SCI will continue to play a critical role in this endeavour.

This is an excerpt from Amit George’s essay “Judicial Review and Arbitral Awards” in ‘[In]Complete Justice? The Supreme Court at 75′, edited by S. Muralidhar and published by Juggernaut Books.