Analysis

Precedential Value: Cases cited in the Article 370 hearings

Our explainer distils the key issue and conclusions in four prominent Supreme Court precedents

In the first week of September 2023, the five senior-most judges of the Supreme Court concluded hearings in the closely watched In re: Article 370 of the Constitution of India. The 16 days of arguments were a deep dive into the historical, constitutional, and political aspects of the abrogation of Article 370. Counsels relied on key precedents and historical events leading up to the abrogation. In this article, SCO looks into four judgments that featured prominently in arguments.

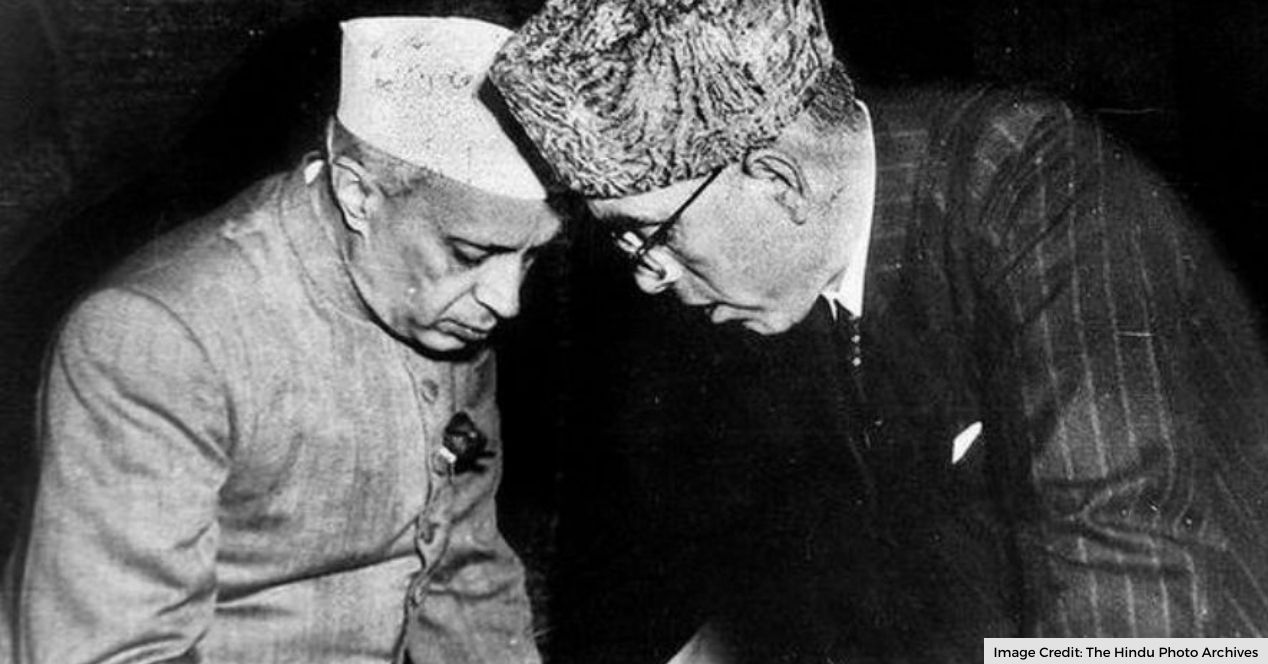

Prem Nath Kaul v Union of India (1959)

Factual Background: This was one of the earliest cases that dealt with Article 370 and the role of the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir. As per Article 370(1), the President of India can apply provisions of the Constitution of India in Jammu and Kashmir, after the concurrence of the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly. In this case, the validity of the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, 1950 was challenged. Maharaja Yuvaraj Karan Singh enacted the law to boost agricultural production by transferring the land to tillers from estate owners.

Issue: Does the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir have legislative authority to make laws after acceding to the dominion of India?

Arguments: The petitioner argued that he had a right over his land, and pleaded to have the Court declare the Act as void and inoperative. He contended that the Maharaja had no legislative authority as a result of Article 370.

Judgement: The Supreme Court upheld the Act affirming that the Maharaja possessed the legislative powers required to enact it. . The fact situation had to do with circumstances that occurred prior to the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir coming into force in 1956. The Constituent Assembly had been dissolved in 1957. Yet, the Bench made observations on the role of the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir. The ruling stated that “[Indian] Constitution makers attached great importance to the final decision of the Constituent Assembly [of Jammu and Kashmir]” ensuring that any “exercise of powers conferred to the Parliament and the President” is “conditional on the final approval” of the Constituent Assembly. The judgement also remarked on the powers of the President to abrogate Article 370. It stated that Article 370(3) “authorises the President to declare by a public notification that this article shall cease to be operative or shall be operative only with specified exceptions or modifications, but this power can be exercised by the President only if the Constituent Assembly of the State makes a recommendation in that behalf.”

Puranlal Lakhanpal v The President of India (1961)

Factual Background: A Presidential Order amended Article 81 of the Indian Constitution to allow representation of Jammu and Kashmir in the Lok Sabha only through indirect elections. The modification permitted the representation of six people from Jammu and Kashmir. The President was empowered to select these members after consulting the Jammu and Kashmir legislature.

Issues: What is the extent of the President’s powers to modify provisions of the Constitution of India while applying them to Jammu and Kashmir?

Arguments: The petitioners had argued that the President “exceeded his powers” and could not make “radical alterations” to provisions of the Constitution while making them applicable to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. They contended that the President substituted direct election with nomination which was not justified under Article 370(1).

Judgement: A five-judge bench of the Supreme Court held that the President has wide powers to modify provisions of the Indian Constitution. The bench dismissed the petitioners’ “radical alteration” argument and observed, “that the word “modification” used in Art. 370(1) must be given the widest meaning in the context of the Constitution and in that sense it includes an amendment and it cannot be limited to such modifications as do not make any radical transformation.”

Sampat Prakash v State of Jammu & Kashmir (1968)

Challenge: The President of India issued an order extending the application of Article 35(c) in Jammu and Kashmir. Article 35(c) was a special provision which provided immunity to preventive detention laws from fundamental rights claims in the state. Originally, Article 35 (c) was inserted through a Presidential Order in 1954, which was later extended in 1959 and 1964.

Issue: Can the President extend the application of an order under Article 370 (1) after the dissolution of the J&K Constituent Assembly?

Arguments: The petitioners argued that “the Article contained only temporary provisions which ceased to be effective after the Constituent Assembly of the State had completed its work by framing a Constitution.” Senior Advocate Dinesh Dwivedi made a similar argument on Day 8. They also argued that the ‘modification’ power of the President should be restricted to minor alterations, an issue that was earlier settled in Puranlal Lakhanpal.

Judgement: Article 370 would continue to exist even after the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir. They explained that Article 370(3) clearly dictates that Article 370 would cease to be operative only on the recommendation of the Constituent Assembly of the State. They held that “no such recommendation was made by the Constituent Assembly [at the time of dissolution].” In other words, Article 370 was permanent.

Maqbool Damnoo v State of Jammu & Kashmir (1972)

Challenge: The President of India issued an order stating that the phrase “Sadar-i-Riyasat” in the explanation of Article 370 of the Constitution was to be construed as a reference to the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir. The Sadar-i-Riyasat was the elected head of the state. The petitioner in this case was detained under the Jammu and Kashmir Preventive Detention (Amendment) Act, 1967, which was enacted after the assent of the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir.

Issue: Whether the petitioner’s detention was invalid because it was not carried out in accordance with the law?

Arguments: The petitioner argued that he was detained under a law that was enacted after taking the assent of the Governor and not the Sadar-i-Riyasat, who was the recognised head of the state under the Constitution of India. Further, replacing the Sadar-i-Riyasat with the Governor could only be carried out through an amendment to the Constitution of India. The Union and the state of Jammu and Kashmir argued that Sadar-i-Riyasat approved an amendment in the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir which made the Governor the competent authority and the head of the state.

Judgement: The five-judge Constitution Bench held that the Governor is the “successor to the Sadar-i-Riyasat.” Further, they agreed with the Union’s contention that the Governor was the head of the state, as per an amendment in the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution, which was approved by the Sadar-i-Riyasat.