Analysis

Will the Supreme Court’s new case categorisation system work?

The new system aims to do away with the overlaps of the old one. We asked Advocates on Record whether it has reduced friction in filing

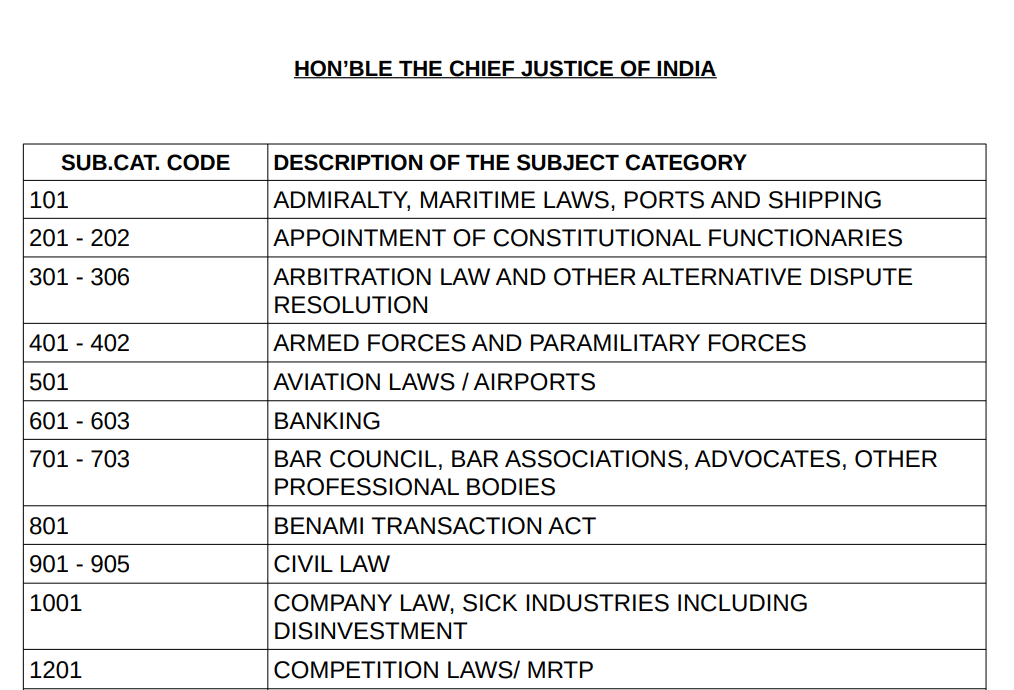

On 17 April 2025, the Supreme Court Registry announced a revamp of the case categorisation system it had been using since 2019. The new system came into effect on 21 April. These changes were recommended by an Advisory Committee led by Justice P.S. Narasimha. The Committee had been formed in 2023 by then Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud.

This article explains how case categorisation shapes the Court’s day-to-day working, outlines the problems that plagued the old system and examines how the revamped system aims to address them.

Categorisation at the Registry

When a case is filed in the Supreme Court, it’s accompanied by a numeric code specifying the category (e.g. Labour and Industrial Law) and sub-category (e.g. Contractual Labour).

Classification helps the Registry determine the court fee. It also helps it list similar cases before the same benches. If there is no instruction by the Chief Justice on coram for a case, the matter is assigned through automatic computer allocation based on the subject code.

According to the Supreme Court’s Handbook on Practice and Procedure, the petitioner, plaintiff or appellant must indicate the category in the listing pro forma. The pro forma is usually found on pages A1 and A2 of the paperbook filed with the Registry.

Shriya Maini, an advocate-on-record (AOR) at the Supreme Court, explained that the pro forma is filled by AORs. Talha Abdul Rahman, also an AOR, added that the clerks of the AOR typically undertake this task. “I think 90 percent of AORs don’t personally check this. It’s routine work for the clerks, and they know from experience what codes need to be indicated depending on the matter,” he said. Sometimes, when the clerks are unsure, it is indicated by the AORs.

A Scrutiny Assistant then checks this code at the filing counter. When a category entry is left empty, the Registry marks it as a defect, which the parties must clear. If the Assistant finds the categorisation unmaintainable for any reason, it is placed before a Branch Officer.

So far, so good. In practice, however, there is usually little transparency when the Registry disagrees with a classification proposed by an advocate. Rahman explained that the Registry can override the indication made by the AOR, with no notice or reasoning. This was because the AoR’s categorisation is not definitive, and not much attention is paid to it.

Maini, however, said that the Registry will seek clarification in such instances. “You must give an explanation with a letter or go in person to explain why a category code has been indicated,” she said.

Categorisation over the years

An explanatory framework document released by the Court highlights the evolution of the categorisation system and why the old one was flawed. The Court had an 18-category system until the early 1990s. But it was facing the problem of bloat—by 1993, there were 48 categories, with more additions made throughout the year. In 1997, when the Court began computerised automated listing of cases, it rationalised the categories down to 45 and introduced sub-categories.

Minor additions to categories and sub-categories were routinely made, but larger revamps took place in 1999 and 2007. Subsequently, more granular details were added in the criminal law category in 2015. These included details like suspension of sentence and anticipatory bail.

In 2019, the Court had 42 categories based on subject matter and length of sentence and five categories based on bench strength. These 47 categories had 307 sub-categories. For example, category number ‘06’ on Service Matters contained sub-categories such as ‘promotion’ (0608) and ‘back wages’ (0617), while the category on consumer protection (38) included a sub-category on appeals under Section 23 of the Consumer Protection Act 1986 (3801).

Repeals and redundancies

The 2019 system was far from ideal. For one, it was not mutually exclusive. This was because categories were not limited to subject matter, but also included bench strength, issues in question, as well as the statutory origin of the dispute. For instance, appealing a death sentence could be categorised under ‘matters relating to capital punishment’ (1401) and ‘Three Judge Bench Matter’ (1900) (since death penalty appeals necessarily need to be decided by a three-judge bench.)

Another complication was that the system was often too particular at the sub-category level. For example, the ‘Contempt Of Court Matters’ category had the sub-categories ‘Suo Moto criminal contempt matters’ and ‘Other criminal contempt matters.’ However, this information was likely irrelevant to the Registry at the stage of assigning the matter to a bench.

The new system was put in place after consultation with members of the Bar and the Registry. It has 48 categories and 182 sub-categories. It also introduces the addition of a ‘P’ tag for public interest petitions, irrespective of the subject. For example, matters relating to public trusts carry the code ‘38’, so a public trust-related PIL will be marked 38P.

Additionally, the new system removes categories based on the quantum of the sentence. Now, this information is only an additional marker while filling up the pro forma. The new system also does away with categorisation based on bench strength and eliminates all references to repealed laws.

Early niggles

“It’s a good step because it eases out the Registry’s work,” Maini said. She didn’t think the additional markers would hold up advocates for too much longer. “When you’re dealing with those laws daily, it’s five minutes of extra work from our side.”

However, there have been instances to indicate that the new system may not have completely overcome duplication-related issues. Earlier this month, a Partial Court Working Days Bench (the new nomenclature for ‘Vacation Bench’) heard a case marked as ‘not falling under any other category’ (4806). The case concerned a petition challenging Hockey India’s administrative decision to dissolve Vidarbha Hockey Association’s membership in the body.

A perusal of the new subject codes shows that there is a category titled ‘relating to other professional bodies’ (0703). It could be argued that this category is sufficiently descriptive of the Hockey India case to be its parent category. Instead, it was placed in the residuary category.

Rahman also raised a concern about the shift being brought in without much prior explanation. While he acknowledged that consultations were held with the Bar, he remarked that there was “no explanatory note on the rationale or impact of these potential changes on daily practice.” He added that it was hard to assess how this change of case categorisation would affect practice. “The codes are probably relevant for the internal software used by the Supreme Court. But we know nothing about it,” he said.

The bigger challenge

In any case, both Maini and Rahman felt that the bigger challenge before the Court was to further streamline the filing process. Maini referred to a circular issued by the Court just before the summer break. This circular requires the Registry to cure all defects and verify the matter before it is mentioned. “If you’re filing something during the vacations, it is urgent by nature,” she said. “But now, the Registry can say, ‘No, we’re not clear about the case categorisation’, for example, and withhold filing.”

Additionally, more than 80 per cent of the Supreme Court’s docket comprises Special Leave Petitions, which are often disposed of at the admission stage after the judges simply read the High Court’s order. Drawing from his pro bono litigation experience, Rahman said that holding up the listing of these cases for (often) inconsequential filing defects was counterproductive.

Often, defects are marked in tranches and not in one go. “Things like insistence on affixing colour copies of photos, which many High Courts don’t insist on, can be done away with as they add to the woes of the litigants”, he said. As an example, he stated that in a demolition matter, the Registry had insisted on colour copies of Aadhaar cards from some slum dwellers who were unable to provide them. The petition was never processed or heard. “The Supreme Court deserves all the respect, but to make it more legitimate, the defect-removal process should not stonewall access to justice,” he said.

Efficiency in court functioning can often be achieved by making minor changes to bottlenecks at the filing stage. Since the new case categorisation system was introduced only a few days before the vacation, it remains to be seen how it will play out once the full Court returns. The early signs are encouraging, but it will be a while before we can conclusively tell whether it has made life easier for advocates and—this might be the taller task—whether it has reduced pendency.

Sarthak is an intern at the Supreme Court Observer.