Court Data

Pendency in the Gavai Court: A report card

Lack of a focussed strategy coupled with a startling rise in filing means that the Supreme Court is hurtling towards 1 lakh pending cases

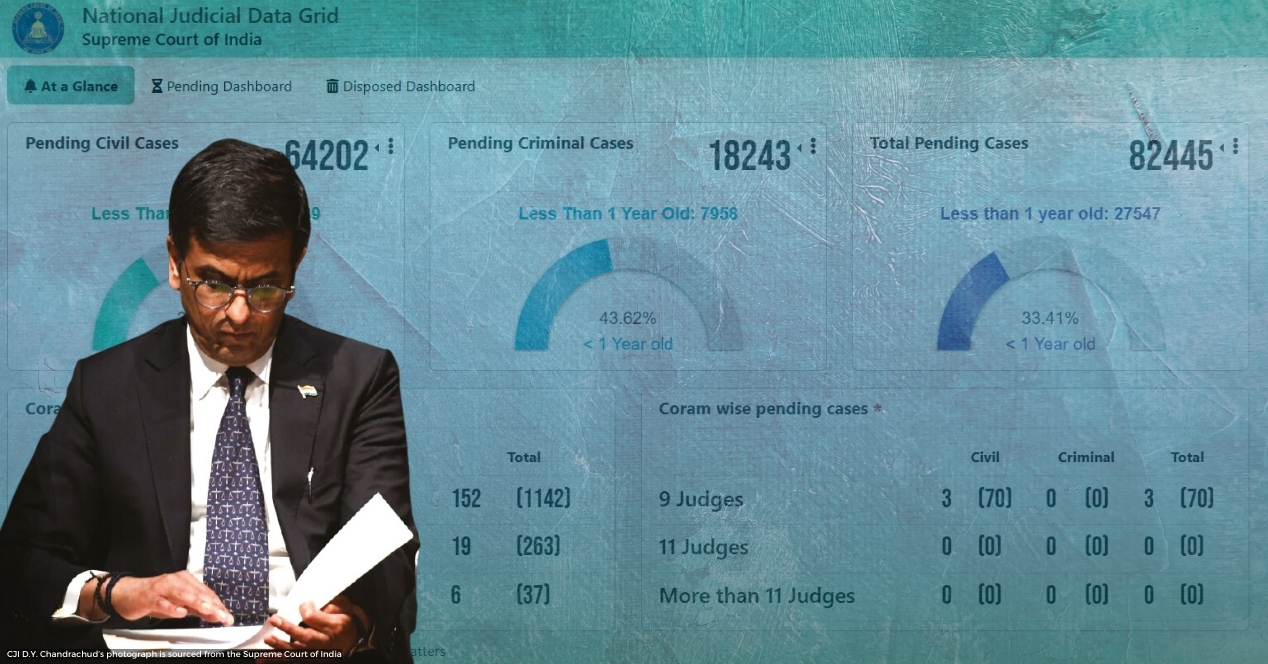

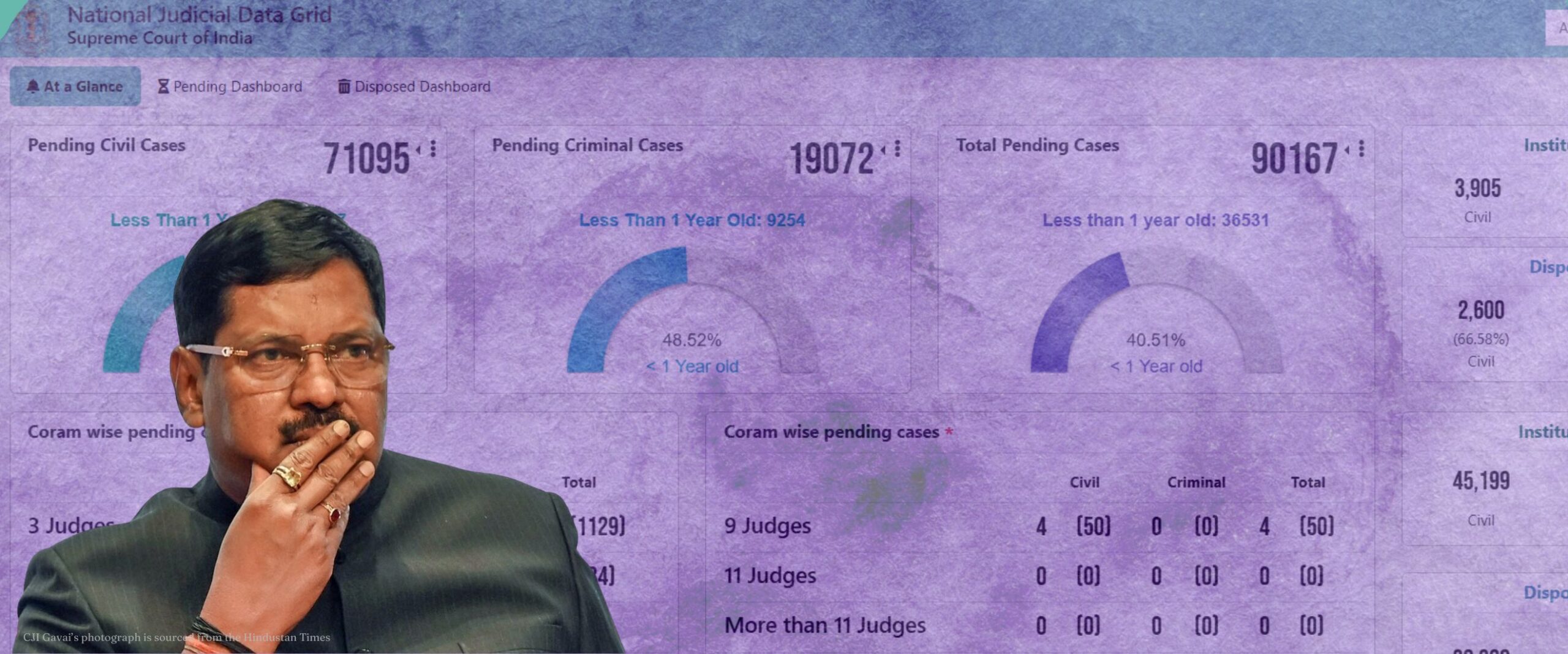

Chief Justice of India B.R. Gavai retires on 23 November after a tenure of six months and 10 days. CJI Gavai’s tenure will be remembered for a few reasons. He was the first Buddhist and second Dalit in the post; his tenure saw the rare occurrence of a Presidential Reference, along with two other Constitution Bench cases. His tenure will also be known for pendency crossing the 90,000 mark for the first time in more than three decades. As of 19 November, there were 90,167 cases in the Supreme Court.

In 1993, which was the last time the figure had crossed 90,000, the Court had a different counting methodology: it double-counted connected matters and appeals in the same case file. There has been one more revision in counting methodology since—in 2022, CJI D.Y. Chandrachud decided to include “all diarized matters which also includes Miscellaneous Applications, Unregistered Matters, Defective matters, etc.” in counting pendency numbers. At the time, the pendency figure had jumped by around 9000 cases—from 70,000 to 78,000. The jump reflected inconsistencies in how the Court had been collecting data, rather than any real surge in pendency.

There was no double counting and no widening of the net in the six months of CJI Gavai’s tenure. So the jump in pendency by 8400-odd cases in six months appears all the more stark. Figure 1 below takes a month-by-month view of pending cases during the tenure.

Pendency figures, however, cannot be assessed without taking into account structural and seasonal changes in the Court. CJI Gavai’s tenure began just 12 days before the Court’s two-month summer break, so this context becomes even more relevant in assessing his record.

Vacations and Bench Strength

The Supreme Court was on its annual summer break for seven weeks between 26 May 2025 to 13 July 2025. The Court hears select cases, typically urgent matters, in this period. Meanwhile, case filings don’t let up as much, leading to a situation where institution far outstrips disposal. So the rise in pendency in June and July is routine and understandable.

We’ve observed this trend in the last couple of years (2023 and 2024), which were the first couple of full years of the Court’s functioning after the stop-start years of the pandemic (2020, 2021 and 2022). However, in the months after the break, pendency typically drops as the Court returns to work in full swing. In 2023, for instance, pendency was 79,636 in May; went up to 81,509 and then was back down to 78,781 by the end of July. We observed a similar trend in 2024 (May: 82,308; June: 84,280; July: 83,312).

The pattern breaks in 2025. The 81,734 pending cases of May had become 87,115 in July and, more alarmingly, 88,047 in August. And this was after CJI Gavai had increased the number of Benches that heard matters in the vacation period (which was rebranded to “Partial Court Working Days”).

Another consideration while assessing pendency is the strength of the Bench. When CJI Gavai took oath, the Court had two vacancies, with three impending retirements: Justices A.S. Oka (24 May), B.M. Trivedi (9 June) and Sudhanshu Dhulia (9 August). However, the Collegium successfully filled all five vacant positions during the tenure. From 29 August, when Justices Alok Aradhe and V.M. Pancholi were appointed, the Supreme Court has functioned at its full sanctioned strength. The rise in pendency cannot be explained away by a lack of bench strength.

Lack of a focussed strategy

A marked difference between CJI Gavai and his predecessors is the lack of a dedicated strategy to tackle pendency. Figure 2 plots the number of pending cases since November 2022, when CJI Chandrachud entered office. The months of his tenure are shaded with a yellow background. His successor CJI Sanjiv Khanna’s tenure is shaded in blue. CJI Gavai’s tenure is shaded red.

In our Report Card on pendency in the Chandrachud Court, we had described his approach as “systematic and deliberate”. Some of the measures he took to manage the sprawling docket included streamlining the process of filing and mentioning, and constituting Special Benches for matters related to death penalty, crime, motor accident claims, tribunals, land acquisition, compensation, direct and indirect tax, and arbitration. He also set up Lok Adalats to fast-track the closure of nearly a thousand cases.

Admittedly, CJI Chandrachud’s tenure was almost four times as long as CJI Gavai’s. This likely enabled him to bring in systemic changes, and for the effects of those changes to play out, which no doubt helped pendency numbers.

However, CJI Khanna too managed to create a dent in pendency, even though his tenure was almost of the same duration as CJI Gavai’s. One of the ways he achieved this was bringing in a significant change that proved unpopular among advocates at first flush—in the first few weeks of his tenure, he halted hearings for regular matters. But the move seemed to have worked in the ultimate analysis.

A publication by the Centre for Research and Policy of the Supreme Court (CRP) notes that, during CJI Khanna’s tenure, it had been tasked with identifying cases that had remained unlisted for years, and also old or infructuous cases that could be cleared quickly. CRP was able to identify 16,000 long-unlisted cases and over 3,000 old or infructuous cases, of which more than a thousand were cleared in one or two hearings.

Rise in institution numbers

The pendency problem has two sides. One is disposal of cases which is a direct result of the Court’s everyday work. The other is the institution of cases or the cases filed and then registered by the Court.

Even if a court is highly efficient at disposing cases, the pendency number can look concerning if the number of filings increase significantly during the same period. Indeed, CJI Gavai’s tenure was marked by a remarkable rise in the number of filings. Four of his six months in office saw more than 7000 cases filed during a month. This figure includes May when he took oath mid-month and excludes November for which data is yet to be published. The two months where numbers were lower than 7000 were June, when the Court was on a partial break and October, when the court was off for two weeks for Diwali and Dussehra.

To put that in perspective, let’s consider the tenures of CJIs Chandrachud and Khanna. Their institution figures generally hovered between 4000 and 5000, hitting 5,949 in July 2024. The first inflection point came only at the close of CJI Khanna’s tenure, with filings exceeding 7500 in one month. In fact, during the tenures of CJIs Chandrachud and Khanna, disposal and institution numbers tracked each other closely in most months, with a few months showing higher disposals than filings. (Refer to Figure 3 below).

Missed opportunities in the Gavai Court

The disconcerting rise in pendency in the Gavai Court can be explained by a lack of a dedicated strategy, coupled with the unforseen—and hitherto unexplained—rise in institution of cases. Senior Advocate Gopal Sankaranarayanan confirmed the difference in approach from the Chandrachud and Khanna Courts. He noted that the Gavai Court “lacked purpose in reducing pendency.” “Perhaps he didn’t realise what was happening to the numbers,” Sankaranarayanan said.

Less than a month before he assumed office, CJI Gavai wrote a two-page note for the CRP publication (titled Unclogging the Docket). There, he noted that the “actual problem of pendency is much larger and such initiatives cannot be a one-time measure”. He added his own suggestions to the report and recommended that similar matters be bundled together, before they are brought to the Court. He also suggested closing cases when the same issues have been settled in another case. But CJI Gavai’s tenure proved that the Khanna experiment remained a “one-time measure”—Justice Gavai doesn’t seem to have followed through on most of his own suggestions.

Rahul Narayan, an Advocate-on-Record, said that it was “not fair” to bring the pendency problem “to the door of any one Supreme Court judge.” “They are larger systemic issues for institution or pendency increases,” Narayan said, while also suggesting that CJI Gavai’s “traditional approach” has been beneficial, including in getting regular matters listed more often. He contrasted this approach with that of some previous CJIs, who, by opting to clear mounting miscellaneous matters, had diverted the Court’s time from pending civil appeals.

Regardless, Justice Surya Kant will inherit a Court in a pendency crisis. But there is cause for hope. He will have the advantage of hindsight, having observed the differing approaches and outcomes under his predecessors. With nearly 15 months in office, he will also have the luxury of time—something CJIs Khanna and Gavai didn’t have. But action will have to be swift and decisive, lest the Court buckle under the weight of its unresolved cases.