Analysis

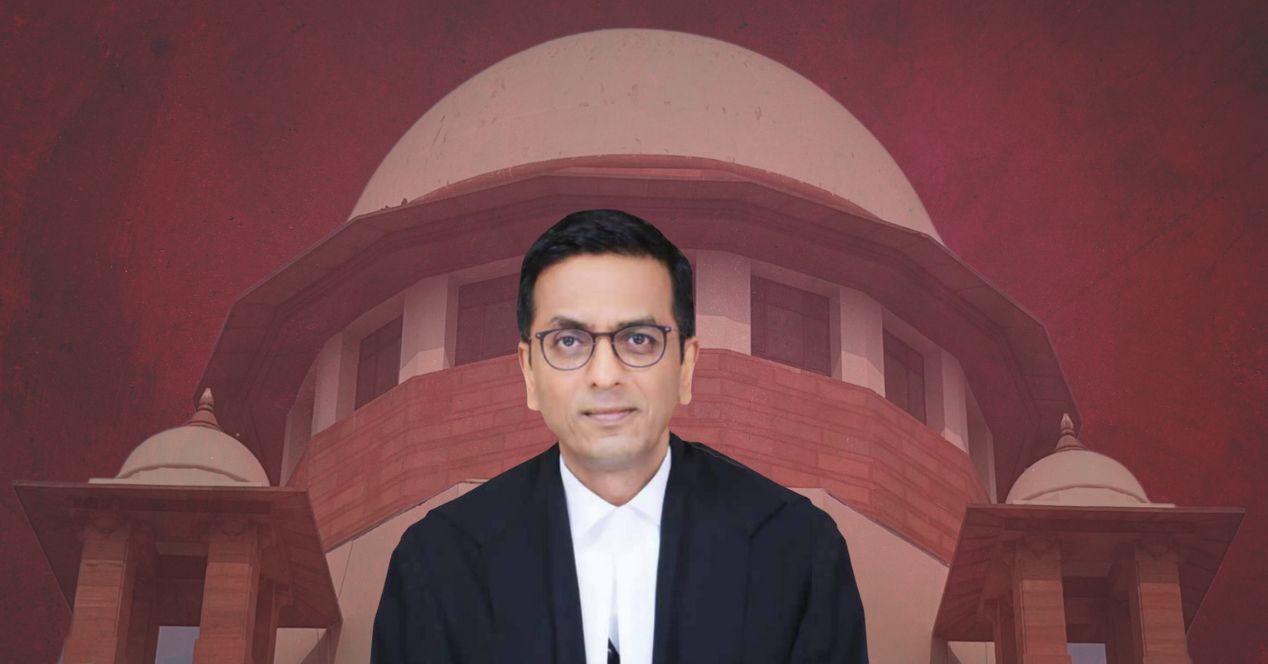

B.R. Gavai, the first Buddhist and second Dalit Chief Justice of India

The new CJI has a reputation of having a sound grounding in the law and Constitution. What are the opportunities and challenges he faces?

Today, Justice B.R. Gavai took office as the 52nd Chief Justice of India. He is the first Buddhist to occupy the post. In his interaction with the media on 11 May, he referred to being sworn in within two days of Buddha Purnima. Justice Gavai comes from a strong Ambedkarite legacy—his father, R.S. Gavai, a politician, had embraced Buddhism along with Dr. B.R. Ambedkar in 1956. Justice Gavai has often spoken about how his choice of profession was inspired by Ambedkar and his father’s dream of Dalit upliftment by the study of law.

After enrolling as an Advocate in 1985, Justice Gavai practised before the Nagpur Bench of the Bombay High Court. He went on to serve as Pleader and Prosecutor for the Maharashtra Government. Although successive Collegiums recommended him for High Court elevation from 2001, his appointment as an Additional Judge of the Bombay High Court materialised only on 14 November 2003. He became a Permanent Judge in 2005 and served until he was elevated to the Supreme Court on 24 May 2019. CJI Gavai will retire on 23 November, after completing about six months in office.

A different approach from his predecessor

From CJI Sanjiv Khanna, CJI Gavai inherits a Court acutely conscious of its public image and which has spent the last few months buffeting criticism for judgements and administrative decisions. It is expected that his approach to restore public confidence will be different from that of CJI Khanna’s, who preferred to have limited interactions with the press.

Justice Gavai was instrumental in organising a two-minute silence at the Supreme Court to express solidarity with the victims of the recent Pahalgam massacre. He took the initiative in the absence of CJI Khanna, who was abroad at the time. “SC can’t be aloof when the country is in danger,” he remarked to justify his intervention.

However, he is far from an activist judge. His decisions and utterances suggest a leaning towards judicial restraint. Recently, while turning down a plea requesting the Union to invoke its Emergency powers in West Bengal, Justice Gavai remarked on the Court being “accused of interfering with the legislative and executive domains.” He was referring to the criticism the Court faced in the wake of its Judgement on the Governor’s powers to assent to state Bills.

This is not to say that Justice Gavai’s opinion has been known to be clouded by media coverage and external chatter. His perception among members of the Bar is of a judge whose decisions have a sound grounding in the law and the Constitution. An early test of his tenure will come in the challenges to the Waqf Amendment Act, 2025, which are listed before his Bench on 15 May.

On occasion, Justice Gavai’s words have also stirred minor controversies. During a February hearing of a PIL related to shelter for Delhi’s homeless (E.R. Kumar v Union of India), he suggested that “freebies” had “created a class of parasites” who were unwilling to work. His remarks prompted CPI(M) leader Brinda Karat to write a protest letter. Some commentators later defended Justice Gavai, noting that such responses could discourage judges from speaking openly during hearings, which was essential to engage counsel.

Notable judgements

Justice Gavai’s reputation of being a judge who plays by the book has been burnished during his time as a puisne judge in the Supreme Court. In Vivek Narayan Sharma (2023), he wrote the majority opinion upholding the Union’s 2016 Demonetisation Scheme. He was part of the five-judge Constitution Bench which upheld the validity of the revocation of special status for Jammu & Kashmir under Article 370. In Association for Democratic Reforms v Union of India (2024), he joined four other judges to declare the Electoral Bond Scheme as unconstitutional for violating the right to information of voters.

In The State of Punjab v Davinder Singh (2024), he wrote a concurring opinion for the holding that it is permissible to create sub-classification among Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes to address inadequate representation. He suggested that creamy layer exclusion (currently applicable to the Other Backward Classes category) be extended to SCs and STs, too. This observation has come in from some criticism, particularly because it was not one of the framed issues in the matter.

In Teesta Atul Setalvad v State of Gujarat (2023), a Bench led by Justice Gavai quashed the Gujarat High Court’s rejection of bail to activist Teesta Setalvad, calling its reasoning perverse. In August 2023, another Bench led by him held that the two-year jail term awarded by a Trial Court to Rahul Gandhi for a remark against Prime Minister Narendra Modi was excessive and devoid of reason. The ruling resulted in the restoration of Gandhi’s membership of the Lok Sabha.

In August 2024, a two-judge Bench of Justices Gavai and K.V. Viswanathan granted bail to Manish Sisodia, former Deputy Chief Minister of Delhi, in the liquor policy scam. Justice Gavai cited the long period of incarceration without trial as the ground for granting bail. The Gavai-Viswanathan Bench also issued a landmark order in In Re: Directions in the demolition of structures (2024), where they held that the demolition of the house of a citizen only on the ground that they are accused of a crime was contrary to the rule of law and separation of powers. The Bench issued pan-India guidelines to regulate instances of bulldozer demolition.

Role as head of the new Collegium

Justice Gavai begins his term with two vacancies in the Supreme Court. His term will witness the retirement of Justices Abhay S. Oka (24 May), Bela M. Trivedi (9 June) and Sudhanshu Dhulia (9 August).

Given that the Collegium headed by him faces great expectations to improve the social and gender diversity of India’s higher judiciary, his non-committal response to a question at the 11 May media interaction was particularly intriguing. When asked about the inadequate representation of SC and ST communities in the higher judiciary, he vaguely responded that “People concerned should be alive to the issue of adequate representation of different sections of societies in higher judiciary.”

His response to a question on the lack of representation of women was more direct. He said that it was difficult to find suitable people but he added that the Collegium will have to take a call on recommending women judges to the Supreme Court.

The prospect of the Supreme Court being left with only one woman judge after Justice Trivedi’s retirement makes this a pressing question. Further, only 107 out of 768 High Court judges are women. The total number of vacancies across High Courts is 354. Twenty-nine proposals cleared by the Collegium are pending with the government.

The Gavai-led Collegium has the opportunity to go further than any previous Collegium in redressing the gender imbalance. There is only one woman CJI across all of India’s 25 High Courts (Sunita Agarwal in Gujarat), but the Collegium would do well to identify meritorious women in the Bar and recommend them for elevation. Will Chief Justice Gavai succeed where his predecessors couldn’t?