Analysis

Maharashtra Political Crisis: The Limits of Supreme Court’s Expiations

While on substantive legal questions the SC made a legally cogent decision, its effect on the ground is limited.

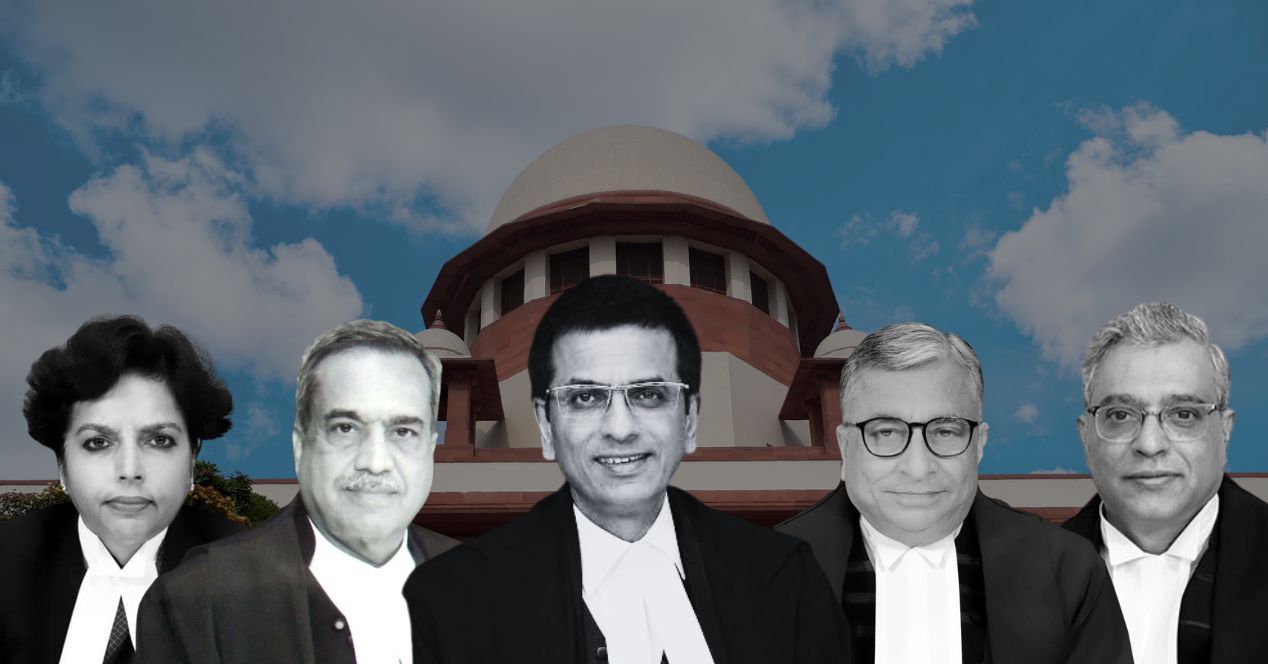

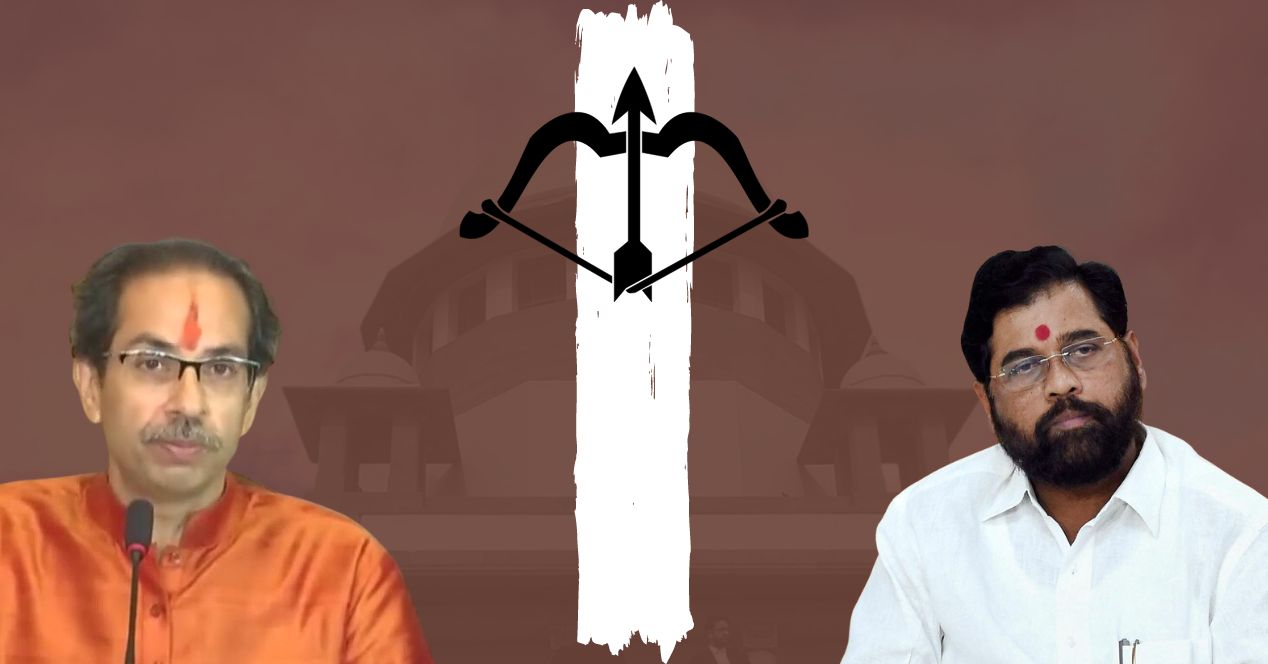

On May 11th 2023, a 5-Judge Constitution Bench led by Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud, pronounced its Judgement on a batch of petitions connected with the political crisis in the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly that saw a change in government in June 2022 amidst the emergence of two factions of Shiv Sena. The political skulduggery resulted in the dislodging of the Uddhav Thackeray-led coalition government of Shiv Sena, Nationalist Congress Party, the Indian National Congress and the formation of a new government led by Eknath Shinde consisting of a coalition of a faction of the Shiv Sena and the Bhartiya Janata Party.

After a section of MLAs led by Eknath Shinde “rebelled” against the state government by defying the directions of the Chief Whip of Shiv Sena, the Deputy Speaker (Acting Speaker) of the Legislative Assembly issued disqualification notices to 16 MLAs. However, a vacation bench of the Supreme Court in an interim order extended the time to respond to the disqualification petitions by 12 days. In the meantime, the MLAs from the Shinde faction issued notice for the removal of the Deputy Speaker and approached Governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari who directed that a floor test be conducted to see if Uddhav Thackeray enjoyed the support of the house. Though the Thackeray faction challenged the order for floor test before the Supreme Court, the Court refused to stay the Governor’s order following which Thackeray resigned as the Chief Minister and the Governor invited Shinde to form the government.

This case raises various thorny issues with major legal and political implications. While the Supreme Court considered and decided multiple legal questions, here I focus on three principal issues that animated the case: Firstly, do the actions of the Shinde faction amount to defection under the 10th Schedule of the Constitution? Secondly, was the action of the Governor in directing Mr. Thackeray to face a floor test a fair exercise of the Governors’ discretion? Thirdly, was Governor justified in inviting Eknath Shinde to form government or can the Court reinstate Uddhav Thackeray as the Chief Minister? After considering these questions, I briefly discuss the larger import of this Judgement and the limits of its attempt to obliquely expiate interim orders passed by the Supreme Court.

Key Findings of the Judgement

On the first question about whether the rebellion by Eknath Shinde and other MLAs against the Chief Minister amount to defection, the Judgement observed that the Court cannot ordinarily adjudicate petitions for disqualification under the Tenth Schedule. Relying on Kihoto Hollohan and Rajendra Singh Rana, the Court held that disqualification of MLAs was up to the Speaker of the House who must decide on the disqualification proceedings within a reasonable period. This has allowed the government of Shinde to continue since the Judgement has not disqualified the 16 “rebel” MLAs. However, the decision of the speaker regarding disqualification can still be subject to judicial review.

The second question regarding the Governor’s decision to order a floor test is perhaps the most crucial one. The Court held that the Maharashtra Governor did not act in accordance with the law in calling for a floor test and that the communications relied upon by the Governor did not indicate that the “rebel” MLAs intended to withdraw their support to the Chief Minister. It further added that the Constitution does not “empower the Governor to enter the political arena and play a role (however minute) either in inter-party disputes or in intra-party disputes”. This is a critical proposition that denunciates the active role that Governors are increasingly playing in the formation of state governments.

On the third question of whether the Governor was justified in inviting Eknath Shinde to form government, the Court found that since the BJP communicated that its MLAs extend their support to Shinde, who also wrote to the Governor staking claim to form government, the decision of the Governor was justified. The Judgement reasoned that since Thackeray did not face the floor test and instead tendered his resignation, the Court cannot quash his voluntary resignation and restore status quo ante by reinstating him as the Chief Minister. Hence, though the court holds the decision of the Governor to conduct the floor text to be illegitimate, the action of government formation that followed this illegal act is effectively legitimised.

Right Verdict, Wrong Time?

Beyond the legal questions in this Judgement, the approach of the Supreme Court in dealing with the Maharashtra political crisis signals larger concerns with the way Indian judiciary operates. While on substantive legal questions, like the validity of the Governor’s decision to call for a floor test, the Court made a legally cogent decision, its effect on the political situation on the ground is quite limited. The Court by its actions and inactions at the time of the crisis, and by legitimising subsequent decisions of the Governor in this Judgement, has effectively made its finding of illegality of the Governor’s action redundant. The two interim orders passed by the vacation bench in June 2022—by extending the time to respond to disqualification and refusing to stay the floor test— effectively allowed the Shinde faction to stake claim and dislodge Thackeray. After almost a year, the final Judgement of the Supreme Court cannot expiate or undo the irreversible political consequences of its interim orders.

While holding that the Court cannot reinstate Thackeray as the Chief Minister, the Judgement observed that if he had “refrained from resigning from the post of the Chief Minister, this Court could have considered the grant of the remedy of reinstating the government headed by him.” This observation is tragic since the Thackeray faction of the Shiv Sena had approached the Supreme Court and challenged the Governor’s direction of a floor test. It was only when the Court refused to stay the order of the Governor to hold the test that Thackeray resigned. This raises the question of why it’s not only important for the court to pronounce the legally right verdict but also arrive at it at the right time.

The Supreme Court has in various critical cases with far-reaching political implications- whether it was on the constitutionality of the roll out of Aadhaar, or the demonetisation of banknotes, or the abrogation of Article 370, or the imposition of national lockdowns during the Covid pandemic—often delayed hearing or adjudicating the issue at the time of the crisis. The delay in deciding the case works as a decision, especially when the Court refuses to restrict the government or the dominant political dispensation to act in ways that are constitutionally questionable. This effectively legitimises controversial state actions since, as this case demonstrates, the issue might become legally redundant or infructuous when it is finally decided.

Mathew Idiculla is a legal consultant and a visiting faculty at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru.