Analysis

Remission policy: A tug-of-war between the judiciary and the executive

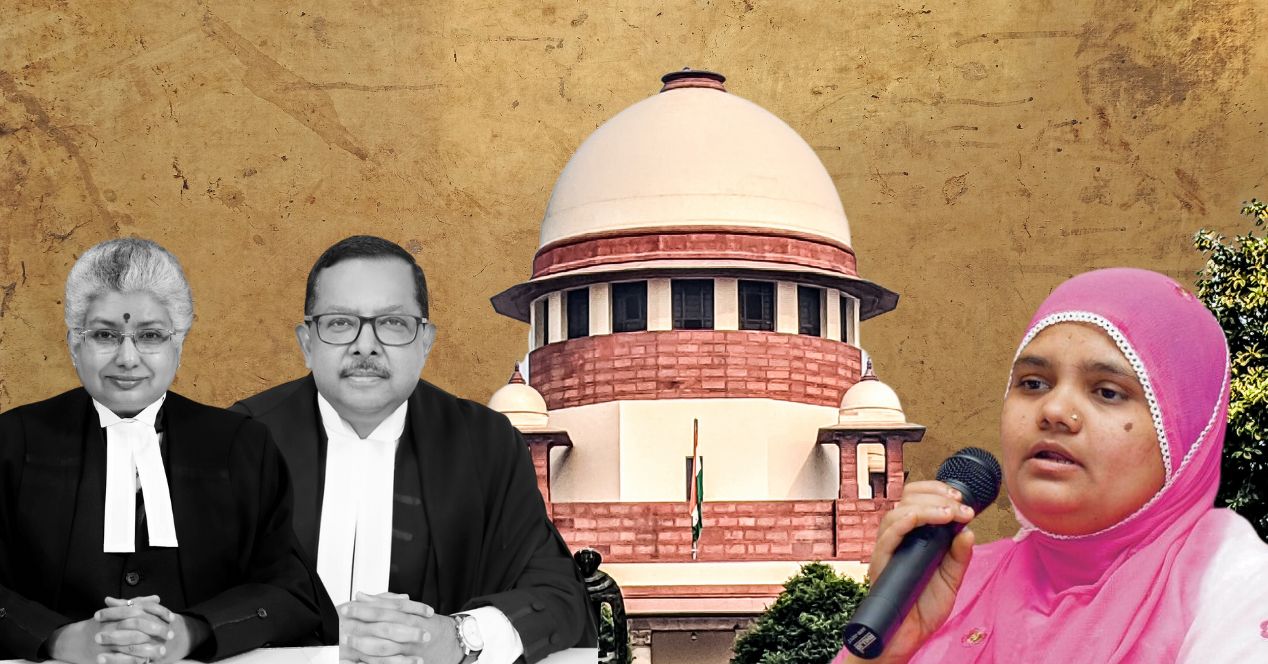

The proceedings in the Bilkis Bano convict remission case have opened up some vital questions about subjectivity and standards

On the 75th anniversary of India’s independence, the nation woke to see 11 released convicts being garlanded outside a jail in Godhra, Gujarat. The men had been in prison for the rape of five women, including Bilkis Bano, and the murder of seven members of Bano’s family, including an infant and her three-year-old daughter, during the Gujarat riots. Later, some of the convicts were reportedly felicitated at an office of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, a sister organisation of the Bharatiya Janata Party.

The men had been released by the BJP-run state government under the 1992 Gujarat Remission Policy, which was in force at the time of their conviction. Bilkis Bano found herself having to approach the Supreme Court again. The first time she did so was two decades ago, in 2003, to request a CBI investigation into her case when the state police failed to get her case off the ground. The year after that, the Supreme Court ordered the shifting of her case from Ahmedabad to Mumbai in response to concerns about the dim possibility of a fair trial in Gujarat.

In early 2008, the trial court awarded life sentences to the 11 men. The Bombay High Court upheld the verdict. In 2018, Radheshyam Shah, one of the convicts, approached the Gujarat High Court for premature release, but the petition was dismissed on the ground that the Bombay High Court would be the appropriate authority.

This prompted Shah to approach the Supreme Court under its writ jurisdiction. In May 2022, the apex court issued an order holding the Gujarat government as the appropriate authority and directed it to consider premature release. The 11 convicts were released within three months. In April 2023, a two-judge Bench started hearing a batch of writ petitions challenging the remission.

Remission policy has moved on since 1992, argue petitioners

The arguments in court so far provide an entry point into a wider discussion about the mode and manner of remission. Appearing for Bilkis Bano, Advocate Shobha Gupta argued that an outdated policy had been applied to prematurely release the convicts of the heinous crime. The 1992 Policy, she argued, was a “simple” one, and the criminal justice system’s understanding of remission had moved on since then.

Gupta argued that the Gujarat government should have considered legal developments that resulted in the new 2014 Gujarat Remission Policy that came into force after a landmark decision of the Supreme Court in Sangeet v State of Haryana (2012).

Gupta’s argument touched upon two issues that arise here. One is a broader concern of the newer policies existing only on paper—the rationale for remissions continues to be shrouded in opacity. The second is an interpretive question of which policy applies: the one that existed at the time of conviction or the one that is in force at the time of the remission?

The ongoing hearings also touch upon a traditional tension between two wings of government. Sentencing is a judicial function but remission is an executive one. But how does the system protect against wantonness or favouritism in the exercise of the executive’s prerogative? The Supreme Court has confronted that question, and put in place certain checks and balances. Since then, states have reformed their remission policies to something more considered and nuanced.

The Central Government’s guidelines for granting Special Remission to Prisoners, released on June 10 last year, also incorporated some of these factors. The guidelines called for prisoners to be granted special remissions in three phases. The first batch of remissions was to be announced on 15 August 2022, the same day on which the 11 convicts were released.

The Supreme Court’s stance on remission

There’s a line of Supreme Court cases in the last 25 years that, when read together, establish the judicial fetter on the remission function. In Laxman Naskar v State of West Bengal (2000), the top Court laid down the following guidelines for considering premature release:

- Whether the offence is an individual act of crime without affecting society at large;

- Whether there is any chance of future recurrence of committing a crime;

- Whether the convict has lost his potential to commit a crime;

- Whether there is any fruitful purpose of confining the convict any more;

- Socio-economic condition of the convict’s family

In Swamy Shraddhananda v State of Karnataka (2008), a three-judge Bench of the Court doubted whether a life sentence till the “last breath” would be “carried out in actuality” by the executive.

Sangeet (2012) was the real gamechanger. There, the Court observed that there is a “misconception that a prisoner serving a life sentence” has a right to release on completion of fourteen years. It held that remission should be granted by the appropriate government only on a “case-by-case basis and not in a wholesale manner.” In February 2013, the Ministry of Home Affairs issued an advisory prescribing that remission should not be granted in a “wholesale manner.”

In Union of India v V. Sriharan (2015), a Constitution Bench deliberated whether an offender can be convicted of life imprisonment till their “last breath”, without the option of remission. This “special sentence” was endorsed by a three-judge majority who viewed it as an “alternative punishment” to the death penalty. Former Chief Justice U.U. Lalit, one of the dissenters, argued that alienating the possibility of remission “is not conducive to reformation.” Since the “special sentence” is not found in any statute books, he felt it “would not be within the powers of the court” to prescribe it.

The 1992 Policy vs the 2014 Policy

In the Bilkis Bano hearings, Gupta relied on this line of cases. She suggested that the Gujarat government had erred by undertaking a bare reading of the 1992 Policy while being “oblivious” to the other factors laid down by the Supreme Court. She noted that remission policies in “broadly all the states” had been amended after the court’s decision in Sangeet.

Gupta indicated that Gujarat’s 2014 policy, which was announced within a year of the Ministry of Home Affairs’ advisory, showed the “wisdom” of the Gujarat government. The Gujarat policy namechecked the Laxman Naskar guidelines and put in place more stringent measures that included considering the “nature of the crime.”

In contrast, the 1992 Policy only discussed three main factors: life convicts must have completed fourteen years in prison, good behaviour, and a favourable opinion by the Jail Advisory Board.

According to Gupta, the heinous nature of the crime should have also played a key role. She referred to Annexure 1 in the 2014 Policy which disqualified prisoners who were convicted of crimes investigated by a central agency (such as the Central Bureau of Investigation), group murders, and rape from being considered for remission.

The chart below demonstrates the key differences between the two policies:

The Gujarat government’s stricter policy, experts suggested, was meant to guard against situations where convicts can find a way out after an arduous trial in case of heinous crimes. “As far as these two policies are concerned, I think the government does not want to be liberal,” said Anjani Singh Tomar, professor at the Gujarat National Law University, “They do not want to give any scope to any person to take advantage out of any policy or any law so they can defy any judgement that has come out after a very long trial.”

In the specific case of Bilkis Bano, Tomar said she did not see any “technical flaw” in the application of the 1992 Policy. She reasoned that the government is “empowered to remit” convicts as per the authority granted by Parliament.

Indeed, the position of law on this is clear. In State of Haryana v Jagdish (2010), the Court confirmed that the policy in force at the time of conviction is the one that should be considered for remission. Further, the Court clarified that any new policy replacing an outdated policy cannot have retrospective application.

From “good behaviour” to “class of crime”

“The opportunity to reform and reintegrate must be given to every prisoner,” Justice B.V. Nagarathna remarked on Day 8 of the Bilkis Bano hearings. Her comment, admittedly off the record, may be seen as a turn away from Sangeet which discouraged “wholesale” remissions.

In judgements like Swamy Shraddhananda, Sriharan, and Sangeet, the Supreme Court has sought to limit the influence of the “good behaviour” factor, which can often enter subjective territory. Further, the apex Court has called for including the opinion of the presiding judge of the convicting court as a mandatory and guiding factor for remission.

Justice Nagarathna’s concern was centred on whether the option to reform and rehabilitate was open for all convicts or just a “privileged” few. Notably, she directed Additional Solicitor General S.V. Raju to provide remission data of all states.

And here lies another pervasive problem. The lack of reliable, granular data about remissions, especially the executive’s rationale for its decisions. From a National Crime Records Bureau report, we know that a total of 2,350 convicts were prematurely released across all states and union territories in 2021. (The NCRB data hasn’t been updated since 2021.).

There’s another roadblock to objectivity and consistency in remission policy. Since remission is a state subject, policies may not be on the same footing. It’s also the reason some experts suggest that the Central Government guidelines on Special Remission are not of a binding nature. “Remission policy differs from state to state and there is little transparency on how these decisions are made,” said Neetika Vishwanath, Director, Sentencing at Project 39A, which is focused on death penalty research. “It means that we do not know how many rape convicts governed by the 1992 Policy were meaningfully considered for remission. It leaves us wondering if the convicts in the Bilkis Bano case were subjected to exceptional treatment when their personal circumstances were considered.”

The Supreme Court has stressed on the “nature of crime” and other relevant factors (Laxman Naskar) to guide the executive to make an informed decision on granting remission. Further, the Central Government’s 2022 guidelines expressly bar extending the benefit of special remission to, inter alia, prisoners convicted of rape, and serving a life sentence. Can this be read as marking a shift from a subjective “good behaviour” approach towards a more objective “class of crime” view of remission? And what does that mean for the reformative goal of the wider criminal justice system?

There’s a view that the Supreme Court jurisprudence, especially Sriharan, takes a couple of steps back in that respect. “While Sriharan permitted constitutional courts to restrict the executive’s power of remission by placing a life sentence beyond the pale of executive remission,” Vishwanath said, “the decision does raise serious concerns about the reformative and rehabilitative goal of prisons.”

In Bilkis Bano, the Supreme Court has an opportunity to weigh in on some of these big issues. Its decision will be eagerly awaited in criminal justice circles for what it could mean for the present and future of remission policy in the country.