Analysis

The Supreme Court on Hate Speech in Elections

What has the Supreme Court said about hate speech in political campaigns?

Counting of votes in Assembly Elections across five states shall begin tomorrow.

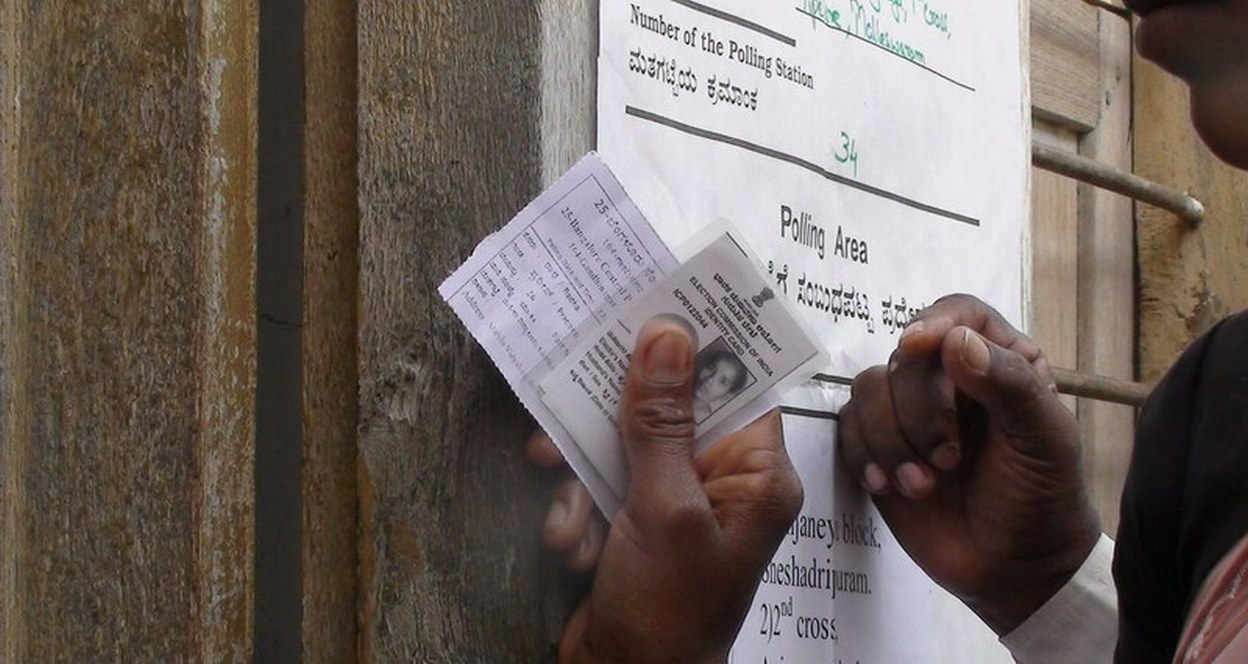

Election season in India is marked by frenetic campaigning, slogans that capture the popular imagination, and extraordinary religious and caste-based polarisation. This election season, reports have surfaced of candidates making inflammatory speeches against religious minorities.

While there are ordinary criminal laws prohibiting hate speech in India, Section 123(3A) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (‘RP Act’) deals specifically with hate speech in the context of electoral campaigns, classifying it as ‘corrupt practice’. Additionally, the Election Commission of India’s Model Code of Conduct forbids political parties or candidates from engaging in activities that promote hatred between communities.

The Supreme Court has engaged extensively with the question of whether caste and communal appeals can be made by candidates during elections. In the context of hate speech in election campaigns, the Court has delivered two prominent decisions—collectively known as the ‘Hindutva’ judgments, that appear to narrowly construe the factors leading to disqualification under Section 123(3A) of the RP Act.

In Ramesh Yashwant Prabhoo v P.R. Kunte, 1995, the Supreme Court upheld the disqualification of a Shiv Sena candidate who made derogatory references to Muslims while contesting Assembly Elections in Mumbai. However, the Court said that mere references to religion in election campaigns, including the use of the word ‘Hindutva’, would not constitute a violation of Section 123(3A).

The Court in Manohar Joshi v Nitin Bhaurao Patil, 1996 held that a political candidate saying that a Hindu state would be established in his campaign did not violate Section 123(3A), as it merely represented a ‘hope’.

More recently, lawyers and activists have filed petitions at the Supreme Court asking it to take action against those purveying hate in political campaigns.

In the run up to the 2014 Lok Sabha Elections, the Supreme Court dismissed two PILs asking the Court to issue directions restricting hate speech during election campaigns. In a different PIL filed in the same period, the Court directed the Law Commission of India to look into hate speeches being made by politicians, and to make recommendations to Parliament on strengthening the Election Commission’s power to curb hate speech. However, the Court reiterated that existing laws covered the question of hate speech in elections. Significantly, the Court said that it would issue directions only when there is a vacuum in the law.

In 2019, the Court reprimanded the Election Commission for not taking action against candidates engaging in hate speech during election campaigns in Uttar Pradesh. The Commission responded by saying that it had limited powers to take action in this matter.

So far, the Supreme Court does not appear to have acted decisively in response to allegations of hate speech in electoral campaigns. The Court has indicated that the Election Commission must assume more responsibility in these matters. However, the Election Commission has argued that in matters of hate speech, it is largely ‘powerless’.

More State and municipal elections scheduled for the second half of 2022. The Karnataka High Court’s Judgment in the highly polarising Hijab Ban case is also awaited. With communal issues continuing to remain front and centre this year, the issue of hate speech in election campaigns is more pertinent than ever.