Analysis

An orderly transition: CJI Gavai recommends Justice Kant as successor

From Chief Justice B.R. Gavai to Justice Surya Kant, the Supreme Court reaffirms its quiet tradition of continuity and convention

On 23 November 2025, Justice B.R. Gavai will retire as the 52nd Chief Justice of India, after a short tenure of six months. With his retirement, the Supreme Court prepares for another change at its helm. By all indications, Justice Surya Kant, the second senior-most judge of the Court, will take over as the 53rd CJI on 24 November. The transition is yet another instance of the judiciary’s adherence to seniority and its commitment to orderly succession.

The appointment of the CJI is grounded in convention rather than statute. It has long served as a stabilising feature of India’s judicial administration. Under the established practice, the Union Ministry of Law and Justice writes to the incumbent Chief Justice, a month before retirement, seeking his recommendation for the next head of the judiciary. The CJI then nominates the senior-most judge found fit to hold the office. The President then formally makes the appointment.

CJI Gavai recommended Justice Kant earlier this week, who will have a 15 month-long tenure until 9 February 2027.

CJI Gavai’s steady tenure

Justice Gavai’s elevation as the CJI in May 2025 carried both symbolic and institutional significance. He became only the second Dalit and the first Buddhist to occupy the top judicial office, reflecting the slow but perceptible diversification of the higher judiciary. His rise from the Bombay High Court, where he served with distinction, was widely seen as recognition of merit combined with representational justice.

His relatively short tenure has been marked by administrative steadiness. He focused on the less visible but essential dimensions of the Court’s functioning such as modernising registry systems, promoting digitalisation and improving case-flow management.

The “Guidelines for Retention and Destruction of Records 2025”, brought out during his tenure, aim to promote coherence, accountability and efficiency in managing administrative records, including institutional decisions, policy implementations, inter-departmental correspondences, audits and engagements with external stakeholders.

The reservations for the Court’s administrative staff roles, announced by him, answered the criticism that it failed to apply its own judgements. The Court’s Model Reservation Roster and Register for Direct Recruitment, uploaded in June 2025, is a milestone in this evolution.

CJI Gavai was credited with restoring the Court’s logo and undoing the glass partitions in the Court’s corridor. He also curbed the practice of oral mentioning by senior advocates seeking an urgent listing. In our mid-term review, we wrote about how CJI Gavai was at pains to stress equality between his office and puisne judges and between the Supreme Court and the High Courts.

His brief tenure was not without controversies. His only woman colleague in the Court and the Collegium, Justice B.V. Nagarathna recorded her dissent over the elevation of Justice V.M. Pancholi to the Supreme Court. CJI Gavai came under criticism for keeping her dissent, leaked to the media, under wraps.

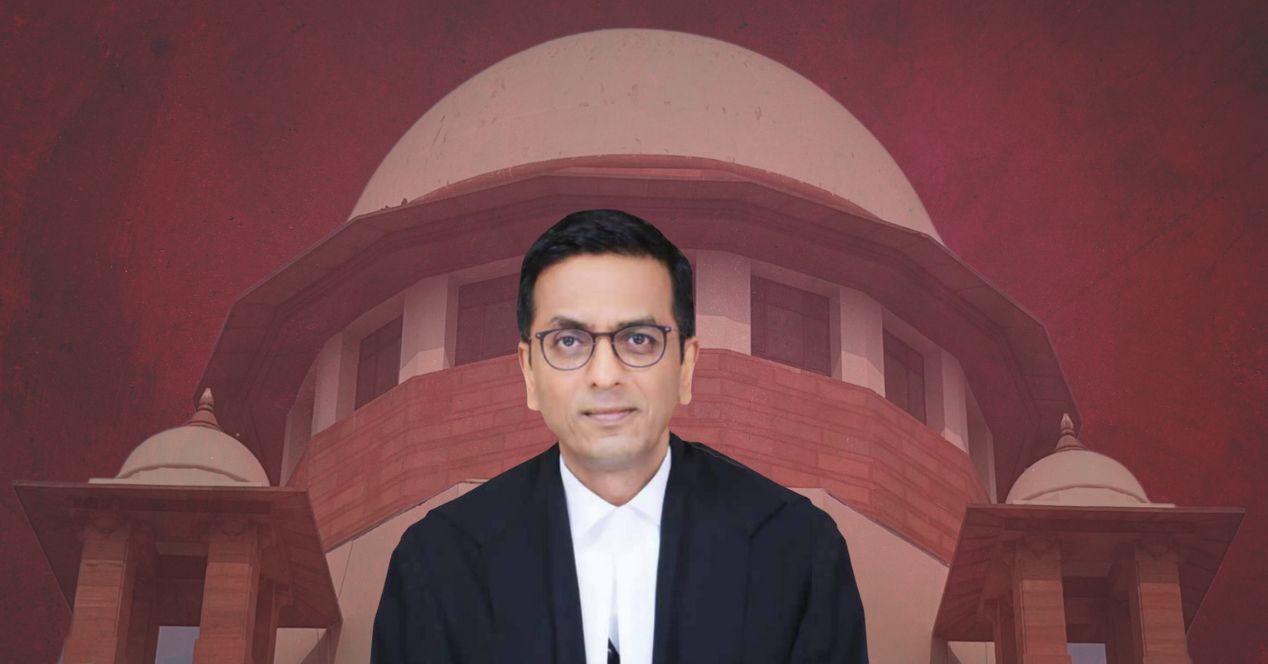

Justice Surya Kant poised to take charge

Born in Hisar, Haryana, in 1962, Justice Kant represents a generation of jurists who advanced through diligence, advocacy and administrative experience. After earning his law degree from Maharishi Dayanand University in 1984, he began his practice in Hisar before moving to the Punjab and Haryana High Court. In 2000, he became the youngest Advocate General of Haryana and was designated a Senior Advocate the following year. Elevated as a Judge of the High Court in 2004, he went on to become Chief Justice of the Himachal Pradesh High Court in 2018 amid a controversy. He was elevated to the Supreme Court in May 2019, alongside CJI Gavai.

Over the past six years, Justice Kant has contributed to over a thousand judgements, covering constitutional, administrative and service law. His opinions often reveal a pragmatic sensitivity to governance issues and procedural fairness. As Executive Chairman of the National Legal Services Authority, he has been instrumental in expanding access to justice, legal aid, and mediation—areas that have increasingly defined the judiciary’s social outreach.

Justice Kant’s upcoming tenure is likely to be reform-oriented. His administrative background makes him particularly suited to address chronic pendency and procedural bottlenecks. Observers expect him to push for deeper digital integration, faster disposal mechanisms and wider adoption of mediation and alternative dispute resolution. His experience with the National Legal Services Authority suggests that his leadership may also prioritise equity and accessibility.

Continuity and convention

The practice of elevating the senior-most judge, though extra-constitutional, has become a vital pillar of judicial independence. By adhering to seniority, the Supreme Court insulates itself from the political speculation that often shadows other constitutional appointments. In the rare instances when this convention was violated, the resulting controversies left lasting scars on the judiciary’s institutional credibility.

Each new Chief Justice brings a distinct style and set of priorities. Gavai’s tenure has embodied calm stewardship and representation; Kant’s may be defined by administrative reform and greater engagement with access to justice. Yet both belong to a continuum of leadership that values discipline, collegiality and constitutional restraint. The institution endures precisely because it knows how to change without rupture.

Challenges ahead

Justice Kant will assume office at a complex moment for the judiciary. The Supreme Court faces a docket exceeding 80,000 cases, alongside a surge in high-impact constitutional litigation involving electoral reform, technology, environmental governance and federal balance. The new Chief Justice’s approach to case management, bench composition, and the listing of constitutional matters will shape not just judicial efficiency but also public perception of the Court’s independence. His challenge will be to maintain institutional continuity while introducing the administrative innovations necessary for a faster, more accessible justice system.

The change at the top, unfolding with predictability and grace, reminds us that the Supreme Court’s legitimacy lies as much in its processes as in its pronouncements. In that continuity lies the Court’s real assurance of stability, and perhaps, its quiet strength.