Analysis

Has the Supreme Court done enough to protect press freedom?

While it has delivered relief in instances, it has a less admirable record in battling the chilling effect of covert forms of press control

In Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) v Union of India (1984), Justice E.S. Venkataramiah quoted Jawaharlal Nehru: “I would rather have a completely free press with all the dangers involved in the wrong use of that freedom than a suppressed or regulated press.” During the 1975 National Emergency, that freedom was curtailed. Censorship orders ensured that only government-approved narratives reached the public, while independent journalism was stifled through legal mechanisms and coercion.

As India marks fifty years since the proclamation of the Emergency, understanding the state of press freedom in contemporary India is inevitable and necessary. While that period from June 1975 to March 1977 was defined by formal and overt State control, contemporary threats to journalistic freedom take a subtler form.

International watchdogs have hinted at the falling standards of free speech and a growing chilling effect. India’s rank of 151 out of 180 in the 2025 Press Freedom Index offers no cause for celebration. Compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), the report places India firmly within the “very serious” category.

However, the Constitution that safeguards the fundamental right to speech and expression is in place and largely intact. At the centre of all this lies a pressing question: How has the Supreme Court responded to more covert forms of press control?

The expansion of reasonable restrictions

Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution recognises the freedom of speech and expression as a fundamental right. The expression ‘freedom of press’ is not found in Article 19, but the Court has situated the right within “the core of speech and expression protected by Article 19(1)(a).” Article 19(2) permits the State to impose reasonable restrictions within eight specified heads.

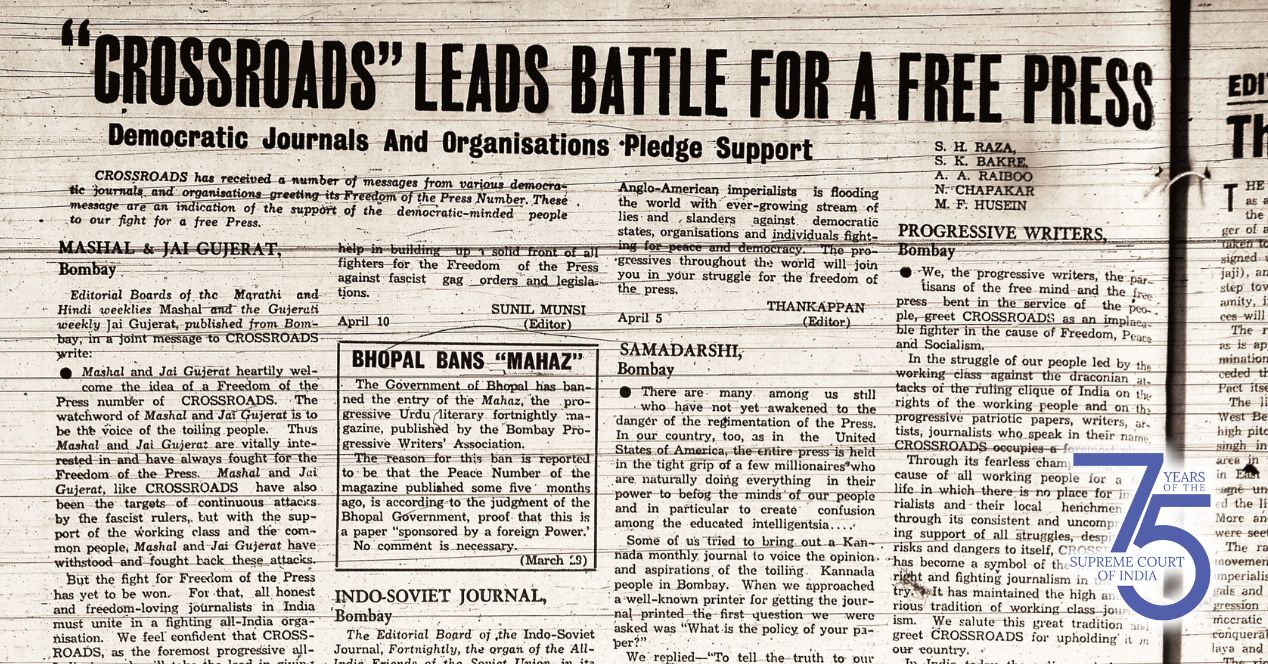

Freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a) was tested early in the constitutional journey. On 26 May 1950, the Court passed two orders upholding free speech. In Brij Bhushan v State of Delhi, it struck down a pre-censorship order imposed on the magazine Organizer by the Chief Commissioner of Delhi. In Romesh Thapar v State of Madras, the Court invalidated the ban that was imposed on the journal Cross Roads, under Section 9(1A) of the Madras Maintenance of Public Order Act, 1949. The provision authorised the state government to prohibit the entry and circulation of documents deemed harmful to public order. A majority of the six-judge Bench held that the restriction was broader than what Article 19(2) then permitted.

Parliament’s response was swift. In 1951, the First Constitutional Amendment expanded the scope of Article 19(2), introducing additional grounds for reasonable restrictions, namely ‘public order’, ‘friendly relations with foreign states’ and ‘incitement to an offence’. It marked the beginning of a recurring tension between constitutional protection and regulatory limits. In Virendra v State of Punjab (1957), the Court upheld a broad pre-censorship order prohibiting Pratap magazine from publishing content related to the “Save Hindi Agitation”. The Court accepted the State’s justification that the publication could provoke public disorder, especially in a communally sensitive climate. It refused to assess the necessity of the restriction, asserting that a presumption of abuse should not be made against the State.

However, in Superintendent, Central Prison, Fatehgarh v Ram Manohar Lohia (1960), the Court adopted a different approach. It held that restrictions on speech must have a clear and proximate link to public order. It struck down a provision used to detain socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia who had urged farmers to withhold irrigation payments. It established that the restriction must not be “far-fetched, hypothetical or problematical or too remote in the chain of its relation with public order.”

A key doctrinal refinement emerged in S. Rangarajan v P. Jagjivan Ram (1989), where the Court observed that any anticipated danger must not be “remote, conjectural or far-fetched” but should have a proximate and direct nexus with the expression in question. The speech, the Court noted, must be “intrinsically dangerous to the public interest,” a “spark in a powder keg.” Legal scholar Gautam Bhatia writes that this analogy situated the contemplated speech in a way that leaves “no scope for any different outcome that could have come about.”

Restriction through production control and defamation

Tracing the contours of press freedom through case law reveals both evolution and inertia. In Express Newspapers v Union of India (1958), the Court held that while the press is not immune from the application of general laws, it cannot be subject to laws which single it out by laying prohibitive burdens, curtailing circulation and dissemination. In Sakal Papers v Union of India (1962), the Court struck down laws which limited the number of pages a newspaper could publish based on its price, effectively forcing publishers to reduce content or raise prices.

A decade on, in Bennett Coleman v Union of India (1972), the Court struck down the Newsprint Order, which limited both the number of newspaper titles a media house could publish and the number of pages per newspaper. The key test was whether the ‘direct effect’ of a law is to abridge the freedom of speech.

The boundaries of State-imposed restriction were once again tested in Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) v Union of India (1984). The Court heard a challenge to an import duty that increased production costs and reduced newspaper circulation. While the Court upheld taxation as a legitimate state power, it directed the government to reconsider its policy in light of press freedom.

In R. Rajagopal v State of Tamil Nadu (1994), the Court held that the State cannot justify prior restraint on publication on the grounds that the material is likely to be defamatory. It upheld the right of a magazine to publish the life story of a death-row convict even without his consent. Prison officials had allegedly attempted to suppress the publication by coercing the prisoner into retracting his approval. It ruled that the press has the right to publish material drawn from public records, and that any defamation claims must be pursued only after publication, not through pre-emptive censorship.

Acknowledging the chilling effect

Before the Court confronted the digital age head-on, Indian free speech jurisprudence lacked a doctrinal acknowledgment of how vague laws can deter expression. In a 2013 article, Gautam Bhatia had noted that the chilling effect doctrine had “virtually no foothold in India.”

A significant breakthrough came in Shreya Singhal v Union of India (2015), where the Supreme Court struck down Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000. Section 66A criminalised online speech that caused ‘annoyance’, ‘inconvenience’, or was ‘grossly offensive’. The Court found this language dangerously vague and detached from the permissible grounds in Article 19(2). The Court rejected the Union’s argument that the internet’s greater reach demanded greater regulation. It held that restrictions on digital speech must still satisfy the threshold of a clear and proximate connection to public order, decency or other specified grounds. In his opinion, Justice Nariman expressly called out the law’s “chilling effect” on free speech.

But implementation proved to be an issue. A 2018 working paper by the Internet Freedom Foundation found that cases under Section 66A were still being registered, investigated and considered by lower courts. In January 2019, the People’s Union for Civil Liberties, one of the petitioners in Shreya Singhal, approached the Supreme Court with the complaint that Section 66A continued to be invoked. The Court directed that the Judgement be circulated to police authorities and all levels of the judiciary to ensure compliance.

In Anuradha Bhasin v Union of India (2020), the Court acknowledged that the right to freedom of speech and expression would entail the use of the internet as a necessary platform for communication and dissemination. Anuradha Bhasin, editor of the Kashmir Times, had argued that the internet shutdown in Jammu & Kashmir had brought the press “to a grinding halt,” forcing her newspaper to cease publication. The Court did not lift the restrictions though it directed the State to review the shutdown orders against the proportionality test, which calls for a legitimate purpose for the restriction.

The Court relied on the application of the doctrine of ‘comparative harm’ to hold that as it had not been ascertained whether other newspapers faced similar restrictions, it would be impossible to judge the legitimacy of a claim of chilling effect. The Court employed this doctrine from Laird v Tantum, a 1972 decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, where it was held that individual allegations of a chilling effect are inadequate to determine objective harm on the freedom of press. The question of the standard for establishing a causal link in a challenge based on chilling effect was left untouched by the Court.

In 2021, several journalists and civil society members approached the Supreme Court alleging that Pegasus spyware had been unlawfully used to surveil them. They argued this violated their rights under Articles 21 and 19(1)(a), particularly undermining the freedom of the press and journalist-source confidentiality. Amnesty International’s Security Lab confirmed Pegasus spyware had targeted 37 devices, including 10 belonging to Indian citizens.

Acknowledging the gravity of the allegations, the Court appointed a committee led by Justice R.V. Raveendran. It noted that “such a chilling effect on the freedom of speech is an assault on the vital public watchdog role of the press, which may undermine the ability of the press to provide accurate and reliable information.” In a 2022 hearing, the Bench orally informed counsel that while malware was found in 5 out of 29 examined devices, the report could not conclusively identify it as Pegasus. In the most recent hearing on 29 April 2025, the petitioners continued to demand that the report, in its entirety, be made public. The next hearing is expected to take place on 30 July.

In Abhishek Upadhyay v State of UP (2024), the Supreme Court granted protection from arrest to journalist Abhishek Upadhyay after an FIR was registered against him under various penal provisions, including defamation. The allegation was based on his X post mentioning caste-based bias in Uttar Pradesh’s administrative appointments. The Bench emphasised that “merely because writings of a journalist are perceived as criticism of the government, criminal cases should not be slapped against the writer.” It directed the state to respond and forbade any coercive action in the interim.

In March 2025, the Court dismissed an FIR filed against Rajya Sabha MP Imran Pratapgarhi under Section 196 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS), for posting a poem on social media. The Court ruled that his speech did not stir enmity between communities and has to be viewed from the mind of a “reasonable, strong-minded” individual, and not one easily offended or overly sensitive to criticism. It further held that in cases involving offences punishable with three to seven years of imprisonment (like Section 196), the police must first conduct a preliminary inquiry under Section 173(3).

Despite some strong judicial pronouncements in favour of press freedom, the Supreme Court’s recent record in cases concerning free speech reflects “a fragmented understanding, doctrinal blurring and added uncertainty” over how it will decide individual cases in the future.” Critics have argued that the Court’s polyvocality has given rise to this incoherence.

The pending question of sedition

The Court is yet to address the constitutionality of speech-restrictive laws such as sedition. In Vinod Dua v Union of India (2021), the Court quashed the sedition FIR filed against journalist Vinod Dua for remarks criticising the Prime Minister’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic in a YouTube video. Relying on Kedar Nath Singh v State of Bihar (1962), the Court reaffirmed that sedition is attracted only when there is incitement to violence or intent to create public disorder. Dua’s video, the Court held, fell within the bounds of permissible criticism of government policy. Dua had requested that sedition FIRs against journalists with over ten years of experience be screened by a special committee before registration. The Court rejected the prayer on the ground that it would encroach a field reserved for the legislature.

In Dua, the Court missed an opportunity to address the unresolved contradiction in the Kedar Nath formulation. By holding that both “incitement to violence” and mere “intent or tendency to cause public disorder” can amount to sedition, Kedar Nath creates a doctrinal confusion in the “bad tendency” and “clear and present danger” test. The latter permits restricting speech only when there is a real, proximate and imminent threat of violence; the former allows for curbs even if violence is a remote possibility.

In 2023, a three-judge Bench referred the challenge to the sedition provision in the Indian Penal Code to a Constitution Bench. The referral indicates a reconsideration of Kedarnath. In July 2024, the new penal laws came into force. While Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 eliminates the term “sedition”, it reinserts its essence in the form of a rebranded offence made up of acts which induce ‘subversive’ or ‘separatist’ activities or endanger ‘the sovereignty or unity and integrity of India’. As opposed to the IPC provision, which had been somewhat judicially curtailed over the years, the new offence has no interpretative precedent.

As the abuse of sedition laws has resulted in years of detention without conviction, broadening the scope of the offence under new nomenclature threatens to continue to have the same stifling effect. The most recent example can be of Ali Khan Mahmudabad, the Ashoka University professor who was booked under Section 152 for a Facebook post criticising Operation Sindoor. Even as he was granted bail by the Supreme Court to “facilitate the investigation”, he was gagged from writing on the topic. Bafflingly, the Bench established an SIT “to holistically understand the complexity of the phraseology employed” in the post.

Weaponisation of criminal law

In Romesh Thapar (1950), the Court recognised that “freedom of speech and of the press lay at the foundation of all democratic organisation.” That Court still reiterates this principle. However, what has changed is the way in which that freedom is now curtailed not by explicitly banning publication, but by invoking law to punish the act of reporting.

A joint report by the Clooney Foundation for Justice, National Law University, Delhi, and Columbia Law School reveals that in criminal cases against journalists in India, delays at every stage have created a climate of fear, financial hardship and disruption. Titled ‘Pressing Charges’, the study analysed 624 incidents from 2012 to 2022, finding that over 65 percent of 244 tracked cases had not been closed, with police investigations pending in 40 percent and only 6 percent ending in conviction or acquittal. Journalists from small towns and regional media were arrested more frequently and secured bail less often than their counterparts in metropolitan areas, with only 3 percent receiving interim protection compared to 65 percent in cities.

Take for instance the case of journalist Siddique Kappan. After obtaining bail from the Supreme Court, Kappan continues to face the burdens of pre-trial restrictions. While speaking to The Hindu, he referred to his life as an “open jail”. Arrested under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967 and the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 while reporting on the Hathras gangrape case in 2020, Kappan was granted bail by the Supreme Court in 2022 on the condition that he report to the local police station in Kerala every week. (This was relaxed by the Court in November 2024.) Until the completion of his trial, he must travel to Lucknow multiple times a month.

In 2023, The Wire reported on a Free Speech Collective study revealing that 16 Indian journalists had been charged under the UAPA, with seven still behind bars.

As recently as January 2025, a two-judge Bench of Justices M.M. Sundresh and Rajesh Bindal declined to interfere with the Jharkhand High Court’s order denying bail to journalist Rupesh Kumar Singh, who has been in custody since July 2022 under the UAPA. The one-page Order did not contain substantive reasons for the refusal.

Singh was known for his reporting on human rights violations and environmental issues in Jharkhand. The Court has consistently maintained through precedents —K.A. Najeeb (2021), Thwaha Fasal (2021), Javed Gulam Nabi Shaikh (2024)—where it has emphasised the need for independent judicial assessment of prima facie evidence and recognised prolonged pre-trial detention as a ground for bail under Article 21. The decision reflects the Court’s cautious and, at times, inconsistent approach to bail under UAPA

The need for clear standards

Unlike during the Emergency, there is no constitutional suspension of rights today; the promise of free speech is undermined through the legal process itself. The use of criminal law as a deterrent, the rise of internet surveillance and the Court’s preference for case-by-case relief—all these factors raise important concerns about the erosion of institutional safeguards and a lack of doctrinal uniformity.

In 2022, while granting bail to Alt News co-founder Mohammed Zubair for tweets posted in 2021, the Bench had observed, “How can we tell a journalist not to write?” Though powerful, such remarks remain symbolic. It is not enough for the judiciary to offer episodic relief while shying away from establishing clear standards to determine restrictions on free speech and address the chilling effect.

It is time that it addresses the issue of the sedition law’s constitutionality in S.G. Vombatkere v Union of India (the Constitution Bench for which has not been constituted since the 2023 referral) as well as the issue of spyware surveillance in the Pegasus case.

In 1984, George Orwell observed that history can be “scraped clean and reinscribed.” In contexts where journalists are unable to report freely, the ability to contest dominant narratives, document abuse or even preserve memory is threatened. As the guardian of fundamental rights, it is for the Supreme Court to apply the law uniformly, clarify doctrinal confusions and avoid kicking the can down the road when it comes to matters involving press freedom.