Analysis

Off the cuff

Casual remarks and comments are a part of the judicial discovery process. But propriety demands that judges be wary of tone and word choices

It could take the form of judicial prompting or unsolicited moralising. But, in the age of livetweeting and livestreaming, the outrage against it could create a chilling effect on productive conversations between judges and counsel. We are, of course, referring to ‘casual observations’ during judicial proceedings, many of which are reported with aplomb and exclamation.

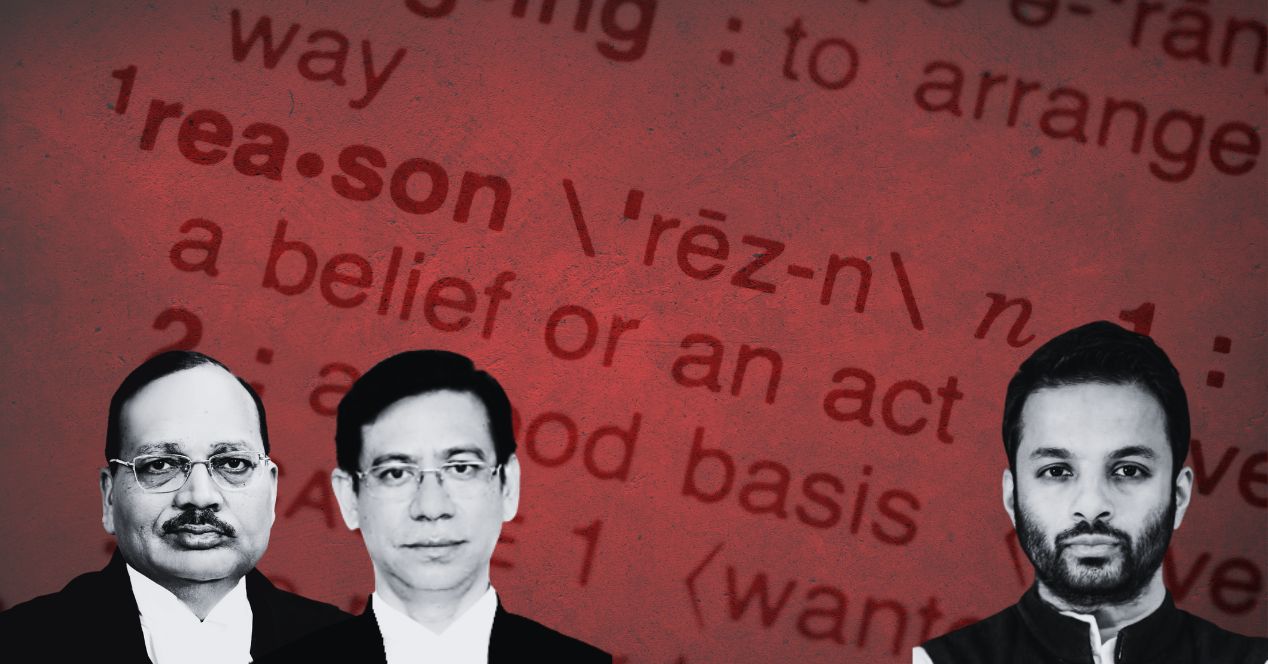

The latest such observation to dominate the news cycle was uttered by Justice Dipankar Datta in the course of a hearing where Rahul Gandhi, Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha, had challenged a summons to him by a Lucknow court in a criminal defamation case.

“How do you know that 2000 sq. km was acquired by China? What is the credible material? A true Indian would not say this. When there is a conflict at the border, can you say such things? Why can’t you ask these questions in Parliament?” This remark was addressed to Abhishek Manu Singhvi, Gandhi’s counsel.

Expectedly, the Order dictated at the end of the proceedings contained neither the “true Indian” remark nor the rhetorical questions. In fact, the Bench accepted Singhvi’s contention that the Lucknow Magistrate could not take cognisance of an offence without hearing Gandhi.

Political leaders and commentators were quick to excoriate Justice Datta for overstepping. The INDIA bloc called the remarks “extraordinary” and “unwarranted.” Senior Advocate Raju Ramachandran equated the comments with the Bombay High Court’s recent questioning of the patriotism of those seeking to protest at Azad Maidan in support of Gaza. An unsigned humour column in The Economic Times quipped that there has been “a strange gear shift in the judiciary,” which has gone “from interpreting laws to delivering unsolicited TED talks on patriotism.”

Justice Datta joins a list of judges whose oral remarks have drawn attention in recent times. In February, Chief Justice B.R. Gavai, while hearing a PIL on urban housing for the poor, asked whether freebies create “a class of parasites.” The context made it clear that the CJI was batting for the integration of the homeless into the mainstream but the choice of the word “parasite” was unfortunate.

The Supreme Court had taken note of casual remarks in The Chief Election Commissioner of India v M.R. Vijayabhaskar (2021). Justice Sanjib Banerjee, then Chief of the Madras High Court, had blamed the Election Commission for failing to enforce health protocols during the polls and, in a moment of exasperation, had suggested murder charges against it for the surge in COVID-related deaths. These remarks were not in the final order, but they live on the internet forever.

In its Judgement, authored by Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, the Court had clarified that “it is trite to say that a formal opinion of a judicial institution is reflected through its judgements and orders, and not its oral observations during the hearing.” The verdict also touched upon the function of oral comments: they provide clarity to the judges and allow lawyers to develop arguments with a “sense of creativity founded on a spontaneity of thought.”

The Court suggested that judges often play the role of devil’s advocate to test the strength of counsel’s arguments. This revealing of a judge’s mind enabled parties to persuade them to their point of view. “If this expression were to be discouraged, the process of judging would be closed,” the Court warned.

In the same breath, however, the Court asked judges to exercise restraint before using strong or scathing language to criticise a person or an institution. While it called out the remarks of the High Court as harsh and the ‘murder’ metaphor as inappropriate, it rejected the ECI’s request to restrain the media from reporting the comments.

The principle of judicial propriety, which the Judgement in Vijayabhaskar stressed, may encourage the Court to hold a mirror to itself in the wake of Justice Datta’s remarks. But contextualising, rather than self-censorship, may be a more appropriate response to the criticism that has followed. With their tone and choice of words, judges must make it clear whether they are clarifying arguments, sharing an off-the-cuff opinion or simply indulging in banter.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!