Channel

SCO Explains: A Chief Justice in the minority: Why does this matter?

15% of dissents by a Chief Justice in a Constitution Bench were in the last two years alone. What does this mean?

Transcript:

Hello everyone, welcome to SCO explains! Today we’re going to talk about an unusual occurrence at the Supreme Court–the Chief Justice being in the minority in a Constitution Bench case.

On 18th October this year, a five-judge Bench of the Supreme Court held that queer persons did not have a right to marry. Though this Bench, led by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud agreed on this central question, it split 3:2 on queer persons’ right to a state recognised civil union, and adoption rights. The CJI, interestingly, was in the minority in this judgement.

On a first glance, this may not seem interesting at all. In a five-judge bench, dissents are expected and are welcome. As the CJI said himself, dissent is the “safety valve of democracy”. A closer look however shows that the Chief Justice hardly ever dissents in a Constitution Bench. In fact, since 1950, a CJI has dissented all of 13 times in a Constitution Bench case.

Legal scholar Nick Robinson and others explain, that the “The Indian Supreme Court…” is “chief justice-dominant.” As Master-of-the-Roster, the CJI is tasked with assigning cases to judges and handpicking judges to hear constitution benches. With constitution benches, where the Court is deciding substantial questions of law, there appears to be no discernable pattern to how judges for the bench are chosen by the CJI. Robinson suggests that the “chief justice is potentially picking benches that are more likely to decide in a way that he favours.”

Professor George Gadbois’s research takes the example of CJI K. Subba Rao. Before being appointed as Chief Justice, CJI Rao dissented 48 times, often, with strong “anti-government” judgements, “more often than any other judge in the Supreme Court’s history.” In his 9.5 month tenure as CJI, not once did he have to dissent with the majority. Gadbois notes that in CJI Rao’s tenure as Chief, there were 167 cases against the Union government, of which private parties won 83 times—a high winning rate not seen under any of his predecessors.

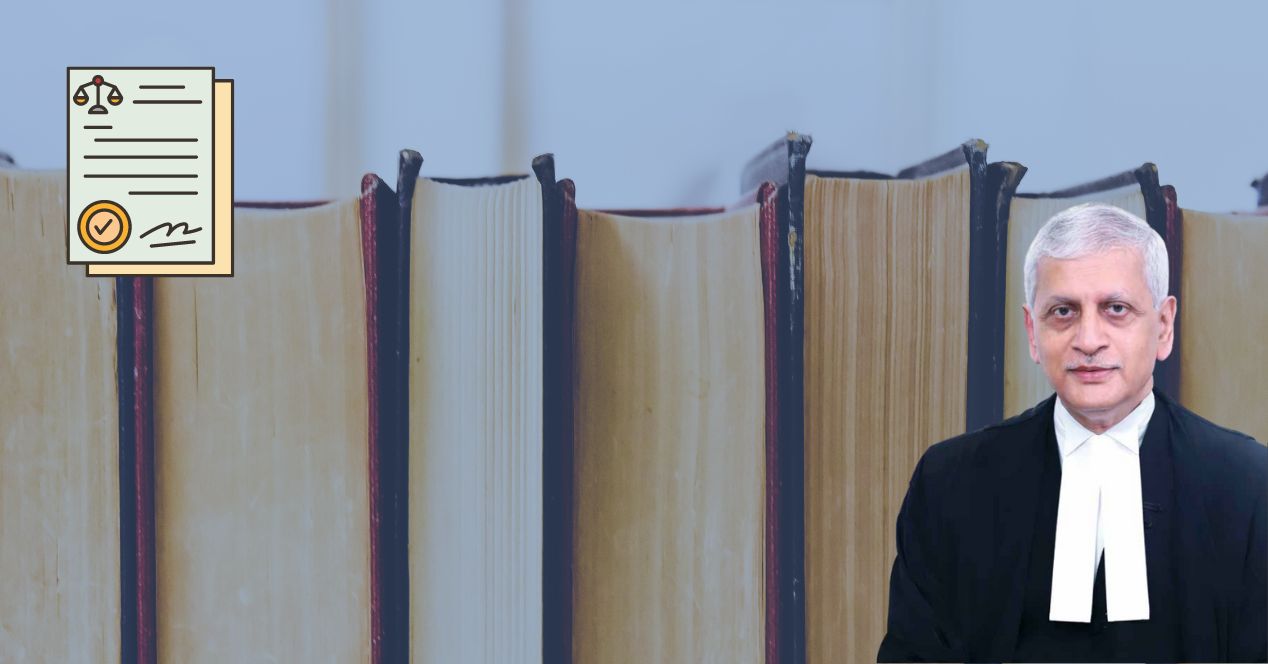

So what does it mean then, that 15% of CJI’s dissents in a Constitution Bench were in the last two years alone? In 2022, CJI U.U. Lalit was in the minority with Justice S.R. Bhat in the challenge to reservations for economically weaker sections, followed now, by the incumbent CJI in the plea for marriage equality. Before that, in 2017, CJI J.S. Kehar dissented in the judgement that declared the practice of triple talaq unconstitutional.

Perhaps this is indicative of a gradual shift towards ensuring the presence of an ideologically diverse bench. This hypothesis may soon be put to test, with a sharp increase in the number of constitution bench cases being heard at the Supreme Court. The fact remains however, that in Constitution Bench allocations, the CJI continues to assign the cases to himself. In the Court’s recent exercise of hearing and clearing pending constitution Bench cases, the Court set up five judge benches to hear the Challenge to Extended Reservations in the Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies, the challenge to immunity enjoyed by lawmakers against bribery charges and the Assam NRC case. The immunity from bribery case, that is Sita Soren v Union of India was referred to the seven-judge bench. Another seven-judge heard the challenge to validity of an unstamped arbitration agreement. Interestingly, the CJI presided over all these cases.