Court Data

Average tenure of Chief Justice expected to drop over next decade

Observers have pointed out that appointing the senior most judge as the CJI has resulted in a “revolving door” which affects stability

Unlike other constitutional heads such as the Prime Minister and the President of India, the Chief Justice of India (CJI) does not have a fixed tenure. Article 124 of the Constitution prescribes the retirement age of a judge of the Supreme Court, including the CJI, as 65 years. A Chief Justice is typically chosen based on seniority, with the senior most judge of the Supreme Court assuming the role. Consequently, the tenure of the CJI is determined by their age and date of elevation.

Six CJIs before a tenure as long as CJI Chandrachud’s

Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud assumed office as CJI on 8 November 2022. By virtue of his remaining years at the Supreme Court, he will serve for two years—the longest tenure for a CJI since 2012. It’s also more than the average tenure of the CJI, which is 1.5 years. In contrast, former CJI U.U. Lalit, held the position for a mere 73 days.

Over 75 years of the Supreme Court, 50 CJIs have come and gone, with tenures ranging from 7.4 years to 17 days. We examine the average number of years a judge serves at the helm of the Supreme Court and how this impacts the institution.

Figure 1 plots the tenure of each Chief Justice of the Supreme Court so far, including the incumbent CJI. On average, they serve 18.1 months—approximately 1.5 years. 34 out of 50 CJIs have had less than average tenure. Bookending the list, CJI K.N. Singh had the shortest tenure of 17 days, while CJI Y.V. Chandrachud had the longest tenure, serving as CJI for 7.4 years.

It has been 12 years since a CJI served a tenure longer than CJI Chandrachud’s 1.5 years—Justice S.H. Kapadia had a tenure of 2.4 years between May 2010 and September 2012.

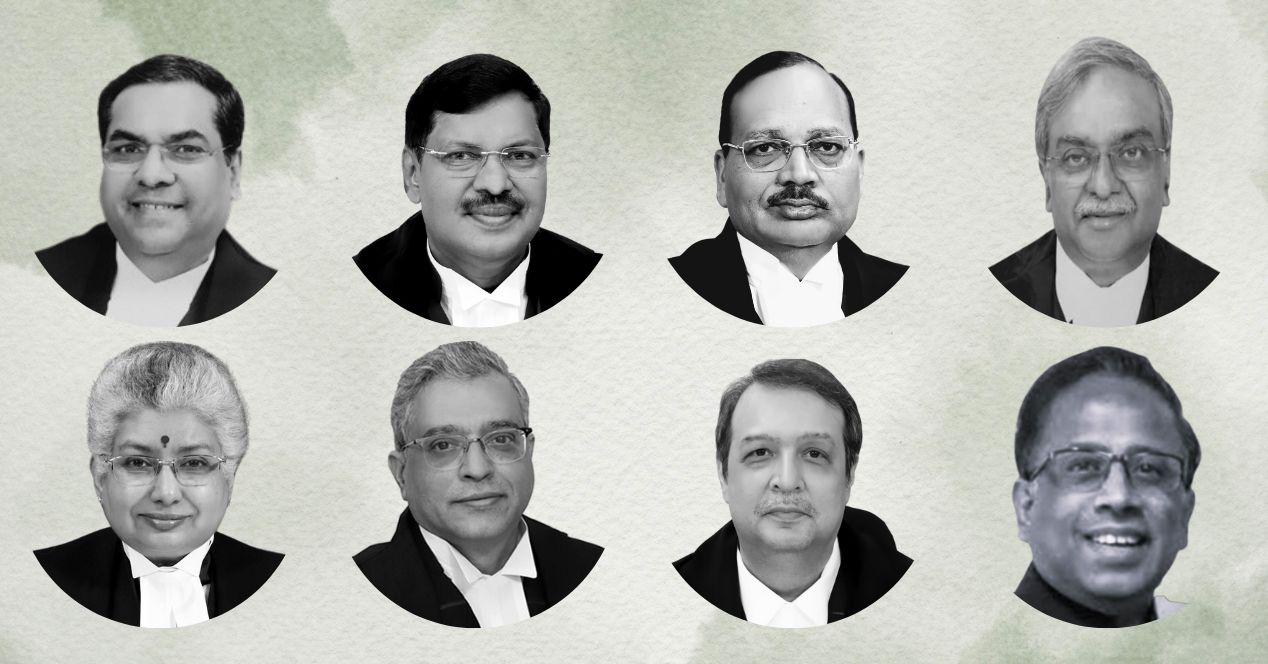

Going by the roster of judges who are expected to become CJIs, the average duration of service is likely to drop in the next few years. If seniority is followed in appointing the next Chief Justice of India, Justice Sanjiv Khanna, will succeed CJI Chandrachud. He will be in office only for six months. Justice B.R. Gavai will follow Justice Khanna with a tenure of 6.4 months. There will be six CJIs before we see a tenure as long as 1.5 years. A calculation of the estimated tenures of the next 8 CJIs indicates that the average time in office will drop to 16.95 months (1.4 years) from the current average of 18.1

So much to do, so little time

When tenures are dictated by age, which leaves the CJI’s with very little time at the helm of the Supreme Court, it could potentially affect institutional stability. Former CJI N.V. Ramana remarked that 65 was “too early an age to retire.” Similarly, Justice L Nageswara Rao had commented that Supreme Court justices should get at least a 7-8 year long tenure, stating that judges face retirement “by the time they understand how the [Supreme] Court functions”.

In India, the retirement age for Supreme Court judges has remained unchanged since its inception. During the Constituent Assembly Debates, the framers had extensively debated the retirement age for Supreme Court justices, with Dr. B.R. Ambedkar remarking that “65 cannot always be regarded as the zero hour in a man’s intellectual ability.”

Academics have pointed out that the practice of appointing the senior most judge as the CJI has resulted in a “revolving door Chief Justiceship.” By the time a judge becomes the CJI, they are quite close to retirement. The CJI is tasked with administrative work that impacts the functioning of the institution. A revolving door situation may result in overnight changes and the undoing of any momentum that might have been achieved during a predecessor’s tenure, “leading to institutional instability.” (see Court on Trial by Aparna Chandra, Sital Kalantry, and WIlliam J. Hubbard).

In August 2023, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice published the 133rd edition of the "Judicial Process and their Reform” report. The committee recommended an increase in the retirement age for both Supreme Court and High Court judges. To support its suggestion, the committee noted advancements in medical science and the consequent increase in life expectancy since 1950.

The report also pointed out that many experienced judges continue to practise as Senior Advocates after retirement. Former Attorney General K.K.Venugopal has often advocated for longer terms for, stating that it is a “travesty” that judges have to retire at 65. During Justice Subhash Reddy’s farewell in January 2022, he said “I can state with conviction that each one of them would be able to perform its duties as a judge of the apex court: justly, fairly, and with competence. One finds lawyers of 70 and 75 years of age functioning at no difficulty whatsoever.” Venugopal himself was 90 years old at the time of the comment, and serving as the Attorney General.

Over the years, the Supreme Court has heard numerous public interest litigations seeking an increase in the retirement age of judges. The Court has dismissed these pleas, stating that it’s the Parliament’s prerogative to amend Article 124. Article 124 was last amended in 2019 to increase the strength of judges at the Supreme Court from 31 to 34.