Analysis

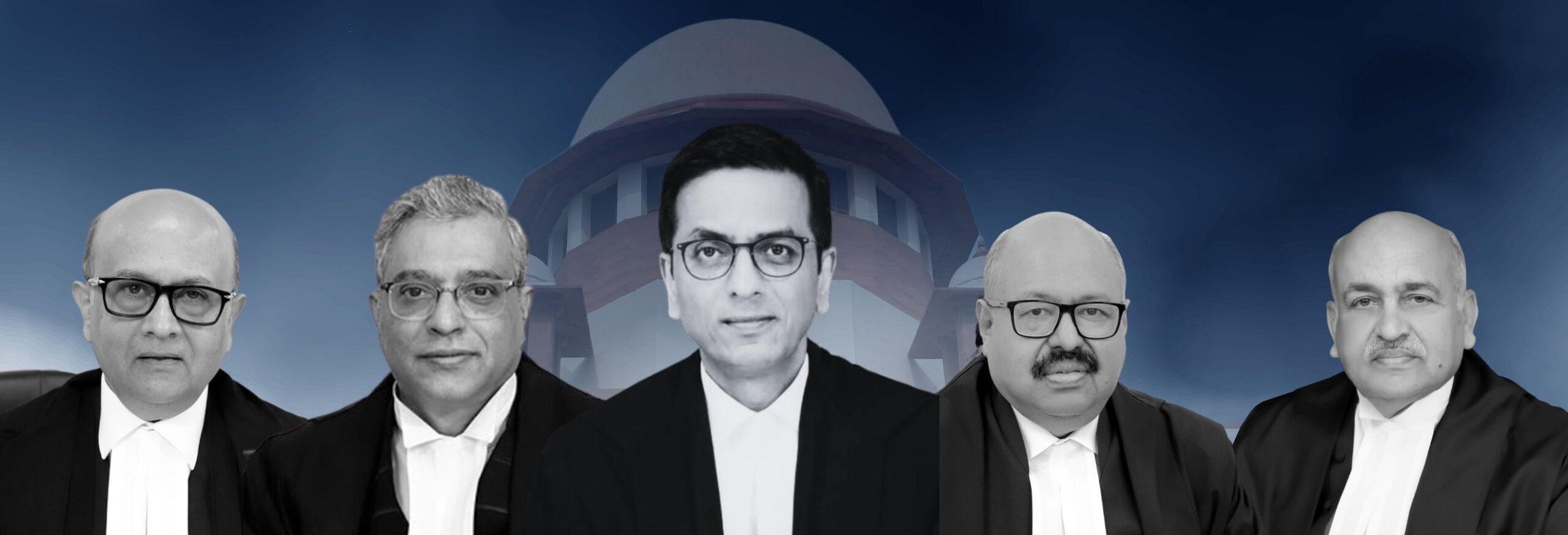

SC Announces New 5-Judge Constitution Bench

This Constitution Bench will hear 4 cases from July 12th, 13th 2023 on appointment to public services, Arbitration and Motor Vehicles Act.

Today, the Supreme Court announced a new 5-Judge Constitution Bench led by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, and Justices Hrishikesh Roy, P.S. Narasimha, Pankaj Mithal and Manoj Misra. This Constitution Bench is set to hear four cases on 12th and 13th July 2023.

1) Tej Prakash Pathak v Rajasthan High Court

The Constitution Bench will decide whether the ‘rules of the game’ in a selection process for a public post can be changed after the process has started.

On September 17th, 2009, the Rajasthan High Court issued a notification under the Rajasthan High Court Staff Service Rules, 2002 (the Rules) for recruiting 13 translators to fill vacant posts. The Rules required candidates to appear for a written examination and a personal interview. However, after the completion of these two steps, then Chief Justice of the Rajasthan HC Jagadish Bhalla, decided that candidates must receive 75% or above in their examination to be selected for the post. As a result, only 3 of the 21 candidates were selected.

The unsuccessful candidates approached the Rajasthan HC in 2010 and then the SC in 2011. They argued that ‘changing the rules of the game after the game was played’ was impermissible and violated their right to equality and non-discrimination under Art. 14 of the Constitution.

A 3-Judge Bench of the SC referred the case to a larger bench in 2011. The Order stated that the larger bench must clarify what rules can and cannot be changed during the recruitment process for public posts.

A 5-Judge Constitution Bench led by Justice Indira Banerjee heard the case in August 2022 and listed it for arguments in September 2022. However, the bench decided to adjourn the case to a later date because of the retirements of Justices Banerjee and Hemanth Gupta.

2) JSW Steel Limited v South Western Railway; Central Organisation For Railway Electrification v ECL-SPIC-SMO-MCML (JV)

The Constitution Bench will hear arguments on the appointment of an arbitrator by a person who is ineligible to be an arbitrator under Section 12(5) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

In TRF Ltd. v Energo Engineering Projects Ltd, (2017) and Perkins Eastman Architects DPC v HSCC (India) Ltd (2020), the SC held that a person ineligible to be an arbitrator cannot nominate a person to be one. However, in Central Organisation For Railway Electrification v ECL-SPIC-SMO-MCML (JV), (2020) the SC permitted the appointment by an ineligible person as arbitrator on grounds that the facts of Energo Engineering and Perkins Eastmen did not apply to the case at hand. The Karnataka HC relied on Central Organisation, and held that the appointment of the arbitrator was valid.

The case was appealed before the SC, on the grounds that in Union of India v M/s. Tantia Constructions Ltd., (2021) had disagreed with the Central Organisation Judgement. Seeing that there was discord between the two decisions of the SC, Justices U.U. Lalit, S.R. Bhat and Sudhanshu Dhulia referred the case to a larger Bench.

3) Bajaj Alliance General Insurance v Rambha Devi

The Constitution Bench will hear arguments on whether a person licenced to drive a ‘light motor vehicle’ under Section 2(21) of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 (MVA Act) may automatically be entitled to drive a ‘transport vehicle of light motor vehicle class’ unladen weight of maximum 7500 kgs. Unladen weight refers to the weight of the vehicle when not loaded with goods.

In 2017, a 2-Judge Bench in Mukund Dewangan v Oriental Insurance Company held that a separate licence was not required to drive a transport vehicle that was categorised as ‘light motor vehicle’.

The appellants in this case argued that 5 main provisions of the MVA Act were not brought to the attention of the Court.

-

- The age of eligibility to acquire a licence for a ‘light motor vehicle’ was 18 (Sec. 4(1)), whereas for a ‘transport vehicle’, it was 20 (Sec. 4(2)).

- Sec. 7 stipulated that a learner’s licence for a ‘transport vehicle’ could only be acquired by someone who held the licence for a ‘light motor vehicle’ for at least one year.

- Sec. 14 states that while a licence to drive a ‘transport vehicle’ is effective for 3 years, if that vehicle is transporting dangerous or hazardous goods, it will be valid for 1 year. Other licences are valid for 20 years.

- Rule 5 of The Central Motor Vehicles Rules, 1989 stipulates that the ‘transport vehicle’ licence holder must have a medical certificate issued by a registered medical practitioner. For holders of other types of licences, a self declaration suffices.

- Rule 31 (2), (3), (4) stipulate different types and duration of training for transport and non-transport vehicles.

The appellants also brought to the attention of the Court that Sec. 3 states that a person may not drive a transport vehicle other than a ‘motor cab or motor cycle’ hired for one’s own use or rented under Sec.75(2) unless the licences specifically permits them to do so.

On March 8th 2022, a 3-Judge Bench of CJI U.U. Lalit, Justices S.R. Bhat and P.S. Narasimha referred the case to a larger bench to review the points omitted by the Court in Mukund Dewangan.