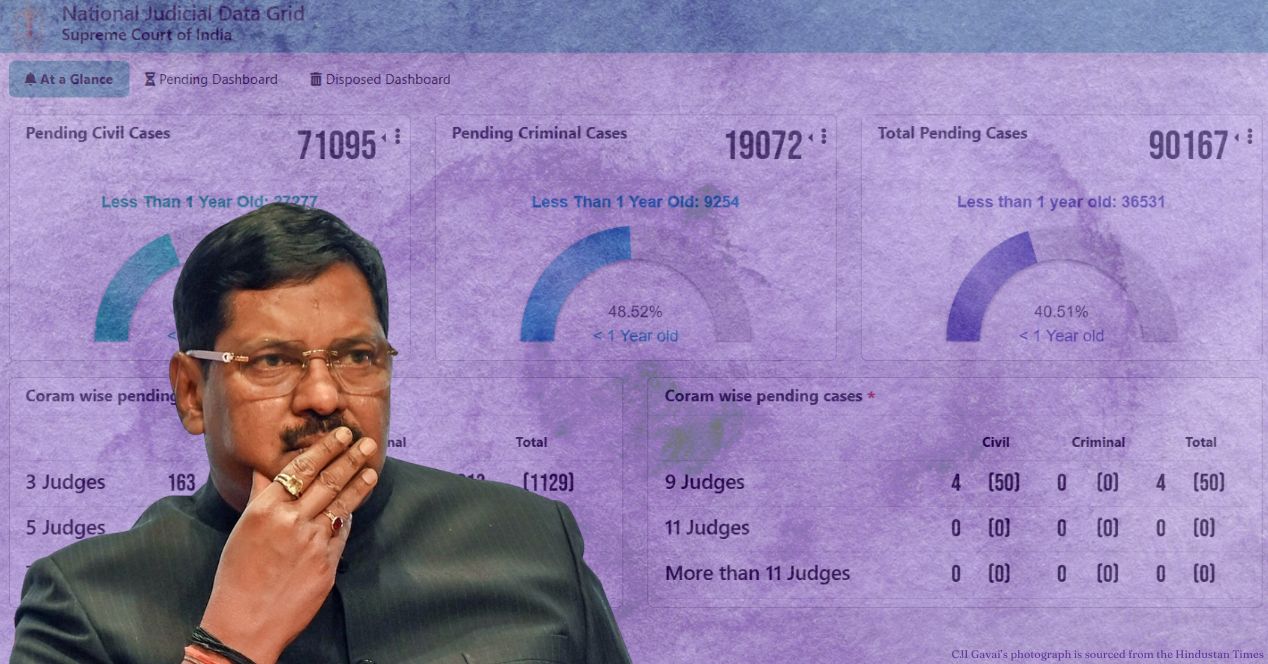

Court Data

The Union Government cleared 96 percent names recommended by CJI Gavai-led Collegium

The rate of acceptance surpasses former CJI Chandrachud who had 4 times the tenure length and CJI Khanna who served for about 6 months

On 23 November 2025, Chief Justice B.R. Gavai will retire after a six month tenure as the 52nd Chief Justice of India (CJI). As the administrative head of the Court, a CJI heads the Supreme Court Collegium, a body of senior-most judges which recommends judges for appointment to both the Supreme Court and the High Courts. While five recommend judges for the Supreme Court, High Court recommendations are made by the three senior-most judges.

When CJI Gavai took oath as Chief, the Collegium included Justices Surya Kant, Vikram Nath, A.S. Oka, and J.K. Maheshwari. After Justice Oka retired, Justice B.V. Nagarathna joined the Collegium.

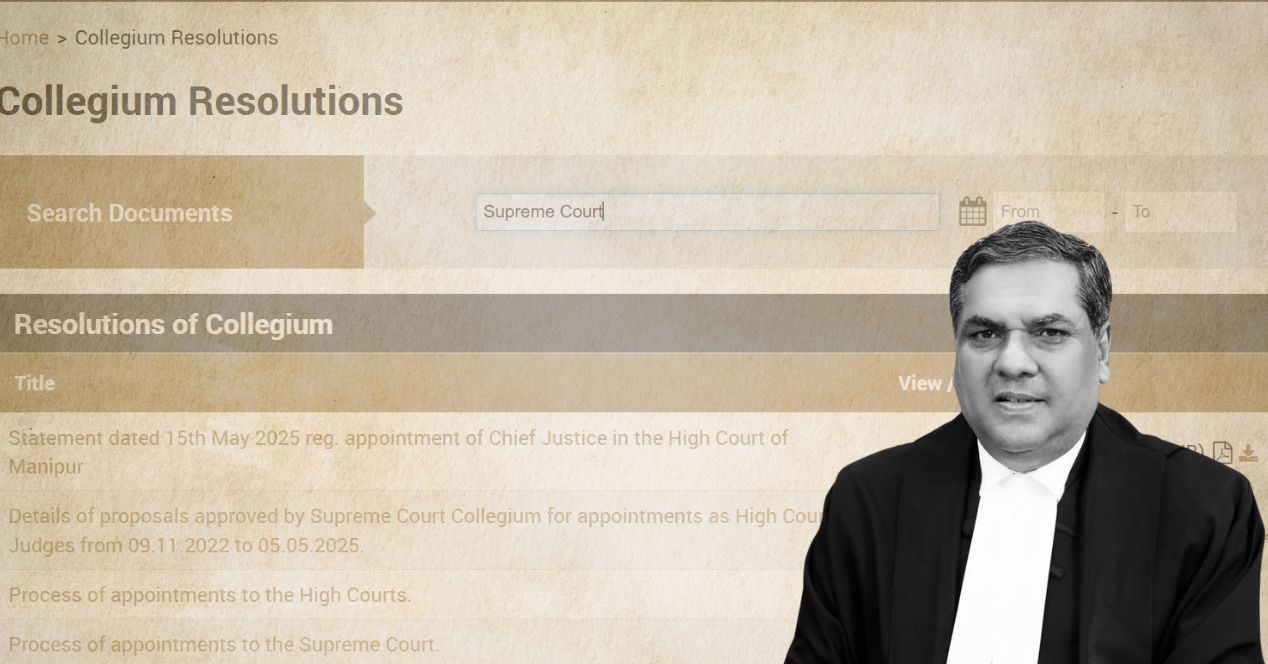

The Collegium publishes its recommendations on the Collegium Resolutions page on the Supreme Court website. The Union government then scrutinises these names. The Department of Justice announces the names the Union government approves through a notification.

When the Union withholds approval, it rarely discloses the reasons for its decision to the public. Tensions have long existed between the judiciary and the executive over approvals of names. Judges of the Supreme Court often respond to concerns about vacancies or representation in the judiciary by pointing out that names recommended by the Collegium are rejected by the Union, or more concerningly, withheld without any explanation.

The CJI Gavai-led Collegium recommended a total of 98 judges for appointment to the Supreme Court and the High Courts. Out of this, the Union cleared 95 recommendations (as of 18 November 2025). This gives the CJI Gavai-led collegium a glowing 96 percent acceptance rate. Contrast this figure with the acceptance rates of Collegiums led by CJIs D.Y. Chandrachud (85 percent) and Sanjiv Khanna (76 percent).

Five Supreme Court judges

CJI Gavai inherited a Court with two vacancies. With Justice Oka’s retirement on 24 May 2025, the Collegium recommended the appointments of Justices N.V. Anjaria, Vijay Bishnoi, and A.S. Chandrukar. The Union cleared their names within five days, and all three took oath on 30 May 2025.

After Justices Bela Trivedi and Sudhanshu Dhulia retired in June and August respectively, the Collegium recommended Justices Alok Aradhe and Vipul Pancholi. The recommendation of Justice Pancholi ignited controversy after reports revealed that Justice Nagarathna dissented on his recommendation, suggesting that his appointment would be “counter-productive” for the Court.

As the Collegium process remains shrouded in secrecy on most occasions, the details of Justice Nagarathna’s concerns never came to light. News reports suggested that Justice Nagarathna had flagged the confidential reasons for which Justice Pancholi was transferred from Gujarat (parent High Court) to Patna. These reports were not officially confirmed. Nevertheless, the Union was quick to accept these recommendations within two days.

Of the five judges this Collegium has brought to the Court, Justice Pancholi is the only one expected to become Chief Justice (in October 2031). Notably, the CJI Khanna-led Collegium had recommended Justice Joymalya Bagchi to the Supreme Court, reasoning that he would be the first CJI from Calcutta since the retirement of CJI Altamas Kabir in 2013. This ultimately revealed that the eventual appointment of a judge of the top Court as CJI is a factor of consideration when it recommends judges.

Like its predecessors, the CJI Gavai-led Collegium did not recommend any women to be appointed as judges to the top court. The CJI N.V. Ramana-led Collegium was the last Collegium to recommend three women to the top court. Justice Nagarathna is presently the only woman judge in the Court.

The Gavai-led Collegium also did not recommend any judges from the Bar. Currently, Justices P.S. Narasimha and K.V. Viswanathan are the only Supreme Court judges elevated directly from the Bar.

93 recommendations, 90 appointments across High Courts

At the start of May 2025, there were 354 vacancies across High Courts. The Gavai-led Collegium recommended 93 judges for High Court appointments, of which the Union government promptly cleared 90 names.

The Allahabad High Court, which has the largest sanctioned strength of 160 judges, received 30 recommendations under CJI Gavai, out of which the Union notified 28. The two names that the Union hasn’t notified yet are Adnan Ahmed and Jai Krishna Upadhyay, both of whom are advocates. This does not necessarily mean the Union has rejected the recommendations. It may simply be mulling over the names.

The Bombay High Court received 17 recommendations, all of which were cleared. Nine other High Courts saw a 100 percent approval rate, namely, Punjab & Haryana (11), Madhya Pradesh (10), Rajasthan (5), Delhi (4), Telangana (4), Gauhati (4), Karnataka (3), Himachal Pradesh (2), and Andhra Pradesh (1).

The Patna High Court received two recommendations, out of which the Union cleared only one; the recommendation of advocate Praveen Kumar remains pending.

The Gavai-led Collegium recommended names for 12 High Courts out of 25. In contrast, the Khanna-led Collegium had recommended names for 13 High Courts. Before that, the CJI Chandrachud-led Collegium had recommended names for all High Courts, except Sikkim.

As CJI Gavai leaves office, there are 297 vacancies across all High Courts. This is 57 less vacancies than he started off with in May.

Vacancies in the High Courts of Madras and Kerala increased during this period. Vacancies in some High Courts, such as Gujarat, reduced despite no recommendation, which likely occurred due to transfers and old recommendations cleared by the Union during CJI Gavai’s tenure.

Near-perfect balance

Out of the 90 names the Union accepted during CJI Gavai’s tenure, 46 were advocates and 44 were judicial officers. CJI Chandrachud’s recommendation pattern was similar with a 50-50 split between judicial officers and advocates.

Interestingly, during CJI Khanna’s tenure, 27 out of 39 appointments were judicial officers. We recorded CJI Khanna’s data around the same time the Court released a manual which included the procedure for High Court appointments. The document stated that 66⅔ posts in High Courts are reserved for Members of the Bar and 33⅓ posts for Judicial Officers (from the district judiciary).

The quotas remain on paper and do not necessarily translate into the appointments. This could be due to various considerations, such as the existing Bar and Judicial Officer ratio in a Court.

Figure 4 shows how many judicial officers and advocates were appointed to each High Court. The figure shows that only advocates were appointed in the High Courts of Bombay, Telangana, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Patna. Meanwhile, the High Courts of Punjab and Haryana, Delhi and Karnataka only had judicial officers among the new appointees.

10 High Court Chief Justice Recommendations

Appointments of Chief Justices to High Courts play a crucial role in the long run. Chiefs of High Courts form the primary pool of judges from which the Supreme Court Collegium picks judges to serve at the top court.

During CJI Gavai’s tenure, the Collegium recommended 10 judges to serve as the Chief Justice of a High Court. The High Courts of Manipur and Patna saw two recommendations each, based on the tenure of the outgoing Chief Justices. Justice Pancholi, whom the Gavai-led Collegium later elevated to the Supreme Court, was first recommended by the same Collegium to be the Chief Justice of the Patna High Court.

The Collegium did not recommend a single woman to serve as a Chief Justice of a High Court during this period. Currently, Justice Sunita Agarwal in Gujarat is the only woman Chief Justice of a High Court.

16 percent High Court appointments were women

Out of the 93 judges recommended to High Courts, 15 were women. The Union appointed every one of them.

The Union’s approval rate under CJI Gavai’s tenure stands out even within this category. Under previous leadership, the Union did not approve all the names of women judges recommended by the Collegium for the High Courts. Some of those names remain pending. For instance, during CJI Khanna’s tenure, six women were recommended, and the Union appointed five of them at that time. Prior to that, CJI Chandrachud had recommended 27 women, out of which the Union appointed 22.

Two unappointed judges from the OBC and minority communities

Figure 5 plots the total number of appointments based on their caste and religious identity.

CJI Khanna introduced the practice of disclosing details of the caste and gender diversity in the appointments made by each collegium. It provided information about the judges and their relatives who were on the Bench in a High Court of the Supreme Court.

The revelation was in the aftermath of the Justice Yashwant Varma controversy where the Court was facing heat over appointments. Following the steps of his predecessor, the Gavai-led Collegium released all details of the appointments. The data also contains details of 17 judges that were recommended during the preceding CJIs tenure and were appointed during the tenure of CJI Gavai.

The data tells us that all recommendations (10) in the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Caste (Minority) were accepted by the Union. Three names are pending approval in the General, General (Minority) and the Other Backward Classes community—Advocates Praveen Kumar (OBC category), Adnan Ahmed (General – Minority), and Jai Krishna Upadhyay (General category).

Unlike during CJI Khanna’s tenure, the CJI Gavai-led Collegium did not recommend anybody from the Scheduled Tribes, OBC (Minority) and ST (Minority) communities.

Has the Collegium and the Union reached an understanding?

The protracted turf war between the executive and the judiciary over judicial appointments appears to have been somewhat blunted during CJI Gavai’s tenure. In contrast, the CJI Chandrachud-led Collegium had been more than touched by this tension. In 2023, Justice S.K. Kaul had pulled up the Union government for its delayed response on Collegium recommendations. Parties had argued that the delay in notifying appointments was a “chronic problem”, leaving judicial appointments in limbo.

In the early days of his tenure, CJI Chandrachud had made an unprecedented move when he released four resolutions to publicly counter the Union’s “security concerns.” Tension between the two branches was high.

This may be explained as the Union government’s resolve to plug vacancies across Courts. Alternatively, the Collegium may be recommending names that the government is likely to accept. The insight into Court functioning that we got from the transfer of Justice Atul Sreedharan presents another hypothesis, which points towards the Union‘s involvement in Collegium recommendations at the stage of discussions. The Collegium’s resolution recommending Justice Sreedharan’s transfer to Allahabad, instead of the originally proposed Chhattisgarh, had explicitly stated that the change was reconsidered at the “Union’s request.”

An end to detailed resolutions?

The Chandrachud and Khanna-led Collegium had their own way of pushing transparency in Collegium recommendations and appointments. For instance, a recommendation of the Chandrachud Collegium was typically detailed—often spanning four pages and containing information about the social and regional representation factors that influenced the recommendation.

The Khanna era was marked by single page statements which carried some information about the deliberations in the Collegium—as seen in the recommendation of Justice Bagchi.

The Gavai-led Collegium was a step back. The resolutions had been reduced to single paragraph statements, with little to no details about a judge’s background. Moreover, there was no information about the factors that the Collegium considered in passing recommendations. The Justice Sreedharan reveal did not explain any concerns of the Union, something which the Chandrachud Collegium had done before.